A Haunted Player - Part 2 of 2

The true nature of the dark forces that tormented a 19th century catcher; how he was rescued; and what he did when the time came to sink or swim.

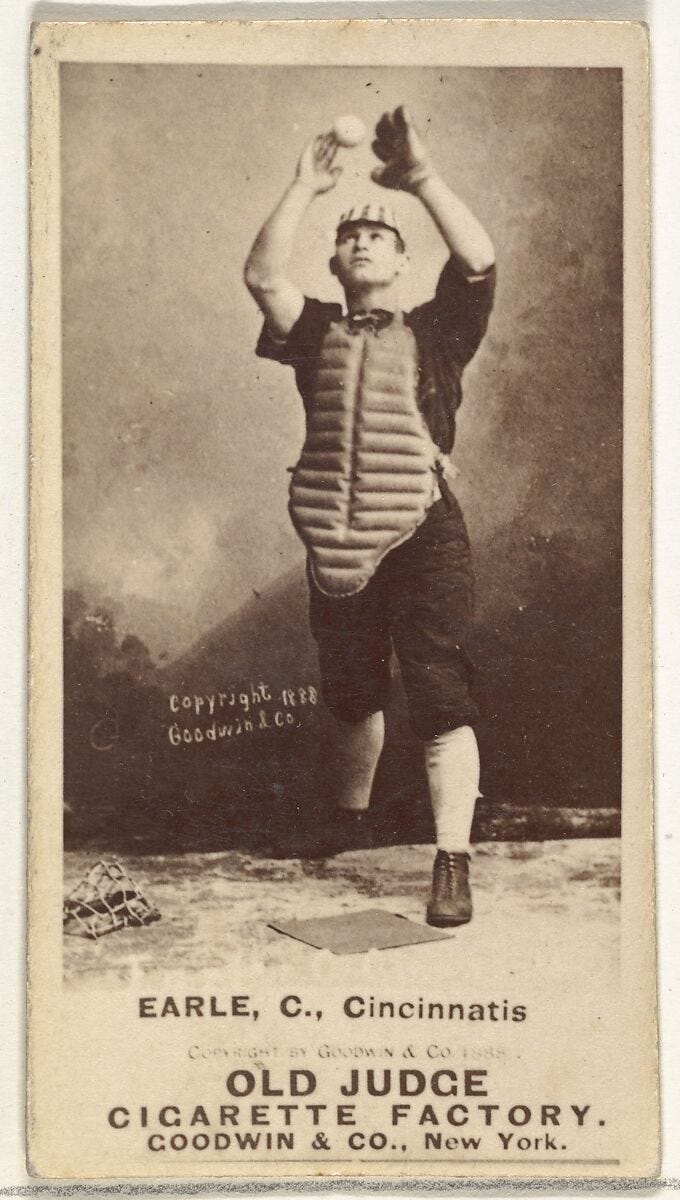

Last week we told one side of the story of Billy Earle, a catcher from professional baseball’s early days, pushed out of one team after another until late 1897, when he abruptly disappeared. This week, in honor of Halloween, we present the Scooby-Doo-esque reveal.

In 1891, roughly a year after he first gained notoriety as an aspiring hypnotist, catcher Billy Earle told a story to Sporting Life magazine, a little anecdote to add some color. For once, he was not the subject:

I am not at all superstitious, and I have never paid much attention to mascots and hoodoo, but during the past season I witnessed what seemed to me a remarkable coincidence relating to the unlucky number 13. In Sioux City [Iowa], where I played, the local street railway company issued metal badges to the players, which entitled them to free transportation on the street cars. By flashing these badges we could ride to any part of the city.

Among the badges was No. 13. Every player that was given this badge was released. One after another the wearer of No. 13 was turned adrift, until everybody was convinced that anyone who got it would be fired. Among the players who wore it and walked the greased plank were [six players], including one man who was turned down twice. When he came back to the club he said, “Give me that 13 badge, I don’t believe in such foolishness.” He put it on, and was released the second time. Finally the badge was given to one of the players and he threw it away.

Earle could not have known it in 1891, but he’d just given an extended metaphor for his own future. There were no uniform numbers in his time, but he might as well have worn No. 13.

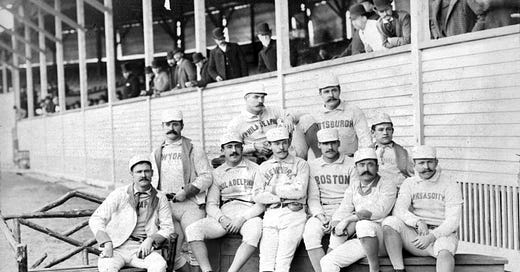

Based on the date of the article, Earle was likely playing for Pittsburgh at the time. After Pittsburgh came Seattle, then Birmingham, then back to Pittsburgh, then Louisville, then Brooklyn, then Minneapolis and finally Dallas, his last steady job before 1897 when he wound up hanging around the Baltimore Orioles, trying to find work and dooming their pennant run in the process.

After Earle left Baltimore that fall, he tried to get a spot on a new semipro team starting up in Butte, Montana, but was turned down. After that, he disappeared. Baseball, it seemed, had finally wised up and thrown him away.

He did not resurface in press accounts until August 11, 1898, when the Cincinnati Post gave an Earle update with one hell of a buried lede (emphasis ours):

The Reds ‘chipped in’ and bought a ticket for Billy Earle, and he traveled East with them. He is going to his old home at Philadelphia. Earle is a morphine fiend and will try hard to brace up.

!!!

Did you see that coming? Be honest.

That offhand blurb in the Post removed the supernatural mask that Billy Earle had been wearing since at least 1894 and revealed a very sick man beneath. He was cursed…by an opioid addiction. Even as the symptoms and stigma surrounding his drug abuse drove him across the country, Earle had managed to keep the truth out of the press, which searched for other explanations and seized upon his colorful hobby.

Billy Earle was an amateur hypnotist, and this vocation did make many of his teammates uncomfortable, which certainly did not help his cause overall. But even in his most active parapsychic years, he may also have been abusing morphine. Hoodoo or junkie, once people knew his deal, they didn’t want to keep him around.

After his morphine habit was revealed, the details of his grim fate received wider coverage. The Cincinnati Enquirer reported that “the little globe trotter has been in hard luck for over a year. For months he has been leading a precarious existence. The drug has impaired his eyesight. Do what he could, Earle could not resist the temptation to indulge his appetite.”

According to these accounts, Earle’s drug use was a relatively recent development. A Nashville paper said that “some years ago in swinging at a ball, Earle wrenched his spine. He was given hypodermic injections of morphine to ease the pain and in that way became a victim of the seductive drug.”

Another paper said the injury happened “in a ball game three years ago, after he twisted the muscles in his back.” This would put the injury in mid-1895 if the report was precisely accurate—but that’s probably too much to ask.

All reports seem to pass lightly over the question of where the morphine came from, but it’s reasonable to imagine there was a doctor involved, even a good one.

“Though it could cure little, it could relieve anything,” David Courtwright wrote in his history, Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in America. “Doctors and patients alike were tempted to overuse.”

Opioids had been in medical bags since the American Revolution, hypodermic needles arrived in the 1850s, and the Civil War mixed the two together to create the United States’ first drug epidemic. The war had left enormous numbers of former soldiers wracked by long-term injuries and begging for any kind of relief. One 1888 survey of Boston pharmacies reported that 15% of the prescriptions they filled were for morphine. By 1895, the other shoe had dropped: 1 in roughly 200 Americans were addicted to opioids.

“Even if a disabled soldier survived the war without becoming addicted, there was a good chance he would later meet up with a hypodermic-wielding physician,” Courtright wrote. That would be even more true of a ballplayer desperate to get back out on the field where he earned his livelihood.

Even though the addictive properties of drugs like opium and laudanum (opium plus alcohol) were well-understood by the 1870s and 1880s (over-the-counter sales ended right around the time of our story), many doctors in that era felt they had no alternative to use in relieving patients’ suffering. Besides, a motivated patient was going to get morphine somewhere, and many physicians felt financial pressure to keep up, despite increasing evidence of the dangers. And even once the problems were understood, the early solutions were rather lacking. In the 1890s, the Bayer pharmaceutical company unveiled a new wonder drug to help treat morphine addiction: heroin. Yes, that heroin.

Morphine and opium were easy to abuse discreetly, and the biggest signs were often behavioral changes. These included loss of energy, a resulting lack of reliability, and eventually the “total loss of physical and mental powers, and actual destitution,” according to an 1887 article which asked if the malady had any cure1.

By the time his habit was made public, Earle seemed to have reached the final stages of the disease. While a half a “grain” of morphine was enough to knock out a new user, Earle said in those years he would inject up to 80 grains of the drug in a day, and even that would not comfortably see him through a ballgame.

Broke, sick, and one mistake away from a fatal overdose, Earle was in Cincinnati in 1898 and still hanging around the ballpark, where he continued to have many friends and acquaintances, including the feisty third baseman of the Baltimore Orioles, John McGraw.

That summer, the Orioles swung through Cincinnati for games against the Reds and McGraw inevitably crossed paths with his old friend.

“He observed Earle very much the worse for the world’s buffetings. The contrast between the Earle of years ago and the Earle of the present day [moved] McGraw.”

He resolved to intervene and try to save Earle’s life. Members of the Cincinnati club agreed to pay Earle’s way across the country on their next trip to Baltimore, McGraw’s home base, and ensure he made it there in one piece. Meanwhile, McGraw himself would make arrangements for Earle to enter inpatient treatment at the Baltimore Hospital. Everything was to be kept secret.

“McGraw took me by force,” Earle said later.

He locked me up until he could get me to a hospital. Then he placed me there to be treated, and when he left me he gave me a round lecture. Then I made up my mind to quit [opioids] or die trying. No one knows what I suffered in that hospital and I think that I deserve credit for quitting, for a man who can take eighty grains of that stuff without flinching is pretty far gone.

It wasn’t quite that clean, according to McGraw: “The first day Earle was there he got out and ran away. He had such a craving for the drug that he sneaked out and got it. He went back, however, and since then he has not touched it.”

The early reports of Earle’s situation read like first drafts of his impending obituary, but Billy Earle did not die, and after a few weeks, his outlook brightened. “The attending physicians think that Earle can be cured of the habit and soon be himself again,” one paper said.

By late September, Earle was reported to be in recovery. “[He] looks much better than he did, and claims to have no desire for the drug which made him a slave for years.” The physician in charge of his case had begun allowing Earle to have supervised visits out of the hospital, usually to a ballpark, and plans were being made for his pending release.

“[Earle] is at the game every day,” McGraw reported. “One of the men at the hospital has taken quite a fancy to him. Earle will be at the hospital two weeks longer. Then the rich man who has become interested in his case will take him to his country home and try and cure him.”

McGraw paid for everything. He also kept silent about the whole affair and was only given away after members of the press noticed the star’s frequent visits to see someone in the hospital and resolved to figure out who. Once declared to be one of the four horsemen of the apocalypse of civilized baseball, his kindness towards one of his fallen brethren cast him in a new light.

Charity covers a multitude of sins, and McGraw has laid up a nice store for himself by his efforts. His efforts on behalf of poor, unfortunate Billy Earle show that the spunky little Muggsy’s heart is in the right place.

In many ways, recovery was far harder in the 19th century than it is in the 21st, and Billy Earle didn’t take the straightest line. He spent six weeks in the hospital, but if he ever showed up at that makeshift halfway house in the country, he didn’t stay long. Just before Halloween, he reappeared in Cincinnati, having made a harrowing cross-country trip to get there.

“I only had six cents in my pocket,” he recalled, “but I wanted to get back to the old town, and I started out to do it or die.”

Dying was a possibility. He slept rough and rode the rails, jumping from train to train and walking when he couldn’t catch one. On one foggy, damp night he found himself clinging to the outside of a baggage car going 45 miles an hour. He had no coat, and nearly froze. But somehow he made it. In Cincinnati he insisted he had been cured and remained sober. He was just looking for work.

“I’ll do what I can get to do,” he said. “No kind of work is too hard for me. I want to make a living and anybody that will give me something to do will do me a great favor.”

Somebody did him that favor, and for a while Earle worked as a waiter or dishwasher, but by 1899 he’d found his way back into baseball. He found a job managing an independent team in Richmond, Indiana, leading the club to great success and returning to the same job in 1900, practically a career-first.

In 1901 he was hired to a slightly-better position, managing a team in Vicksburg, Mississippi in the Cotton States League. The team had been on the verge of disbanding, but Earle led them to within a game of the league championship, becoming the toast of the town. He was reportedly “gifted” the franchise by the prior owner in 1902 and remained with that team in 1904, when the local Vicksburg Post ran a feature on the colorful life of the team’s player/owner/manager.

“His ‘ups and downs’ have been many,” the Post reported, giving an exhaustive, nearly complete account of every team he had played for, and when. The unflinching biography even addressed his opioid addiction.

His fall was due to excessive use of morphine. Earle makes no secret of having been a victim of this habit and to it he attributes his fall from the big leagues. He calls his condition, when under the influence of the drug, the “hoodoo.”

We did a double-take at that:

He calls his condition, when under the influence of the drug, the “hoodoo.”

By 1904, Billy Earle had properly used the term “hoodoo” many times in his career and as early as 1890 he had been labeled one himself. A “hoodoo” was an object (a person, in his case) that brought uncanny bad luck. The term had no connection to drugs or drug abuse, and yet here he was, explaining that his own personal “hoodoo” was morphine addiction.

The life and labors of a baseball catcher in the late 1800s were grinding and often brutal, with minimal protective gear and an endless parade of bruises, breaks, and repetitive stress injuries. What if he’d been using opioids as early as 1890, when he’d first been marked as a talented nomad who inexplicably could not keep a job?

If morphine was Earle’s “hoodoo,” perhaps morphine also made him a hoodoo to others, and not the “hypnotism racket,” which was merely a convenient and distracting cover story. Perhaps the whole eerie mythology of Billy Earle had taken root and flourished because no one knew how to talk about his real problem until the day John McGraw decided the time for talk had passed.

Things eventually fell apart in Vicksburg (briefly resuscitating rumors of the hoodoo), but Earle seems to have remained sober through the ups and downs. He took over another club in Columbia, South Carolina. He umpired for a while, but didn’t care for it. In 1915, at 48 years old, he landed in Omaha, Nebraska, considering becoming a firefighter but again in need of short-term work.

“I was always a good swimmer,” he said, “but didn’t figure to capitalize on it. I wasn’t doing anything in the spring of 1917 when a friend told me the park department was looking for a lifeguard. I guess I was competent.” He held that job for the next 24 years.

The Omaha World-Herald kept track of the local pool’s cheerful, unassuming celebrity, publishing a list of what a life of catching baseballs using only a finger glove had done to his body.

Earle has had chronic arthritis for the past ten years (this was in 1935). His legs are in horrible shape, a source of great pain and badly bowed. His right eye bone has been broken in two places2 and the breaks can be felt today. He has a broken knee cap, and the knuckle of the first finger was split and the bone pushed back into the hand. The tip of one finger is off.

“Players are much better equipped now than in my day,” he said, rubbing a shin.

Despite his injuries, Earle was a cheerful and industrious septuagenarian. In 1939, he returned to Sioux City, Iowa as the guest of honor at an old timers’ game. It was noted that while playing there, he had once caught 119 straight games wearing only a glove.

He gave his last interview in 1941. Nearing 75, he was still working as a municipal lifeguard. And his mind was still sharp: he recalled the names of nearly every player with whom he’d traveled the world back in 1888-89.

He also talked the most controversial aspect of his past, the only instance we could find in the 20th century when he did so:

“Here’s an angle you might like,” he told the reporter, chuckling.

I dabbled in hypnotism in the offseason when I was younger. I was pretty poor as those fellows go. But I’ll never forget one season I accidentally stepped on a fellow’s bat about the time he was in a slump. Like a lot of superstitious players—there were many—he figured I hoodooed him. Boy, was I unpopular!

Billy Earle died at home on May 30, 1946. He had no remaining family, so the city of Omaha paid for his funeral expenses; his co-workers from the pool stepped in as pall-bearers.

The World-Herald announcement of his death was short, with no mention of his time as a quasi-paranormal figure or his years of morphine abuse and recovery. For the sake of brevity, Earle’s life was summed up in the three accomplishments that mattered the most him as he looked back on it.

Billy Earle, the paper wrote, had a long career as a professional catcher. He had participated in the famous Spalding world tour, one of the youngest players invited. And:

As a lifeguard at the Morton Park Pool, he was always proud to say he had taught more than 5,000 youngsters to swim.

Did you see that coming? Be honest.

Billy Earle goes straight into the Project 3.18 Hall of Fame for his knee-buckling narrative curveballs. Mesmerist, hoodoo, morphine fiend, and…beloved figure at the local pool? Legend.

Small programming note: we are off next week, our first bye since February. Wow, right? We’ve had quite the streak to start things off.

We’ll be back on November 11 with a new story, and the archives are there if you have any backlog you’ve been meaning to get to.

One More Thing

Special credit and thank you to author and researcher David Nemec, whose extensive Society of American Baseball Research biography article helped us get our bearings in Billy Earle’s fascinating but confusing life in baseball.

There was a remedy for morphine addiction, the article said: a patent medicine called “Warner’s Safe Cure.” The cure was apparently a concoction of vegetable oils, and while you might assume that “safe” was in reference to the properties of the medicine (i.e. “safe to consume”) you would be wrong. “Safe” was actually a branding reference. The company producing the cure was better known for their line of locking secure storage boxes. They even put a drawing of a safe on the bottles.

Protective masks were available by the early 1880s, but Earle he seems to not have used them. Nothing more old school than a broken orbital bone.

Wow, Paul, I definitely did not see that coming! He certainly had an eventful life. That ‘cure’ for morphine addiction sounds like a bust. I think that the most surprising thing to me was that at about age 50 he worked for 24 years as a lifeguard. I have a question for you: is a “finger glove” just an old term for a baseball glove, or were they referring to the fact that he didn’t use a catcher’s mitt? Another interesting issue of your newsletter. I look forward to November 11. Have a great bye week! Meg

Paul, I did not see the morphine and lifeguard twist coming in this story - quite a piece!