A Monumental Catch - Part 1 of 2

Just a few weeks after the Washington Monument was completed, major league baseball players were circling underneath, trying to do what many people thought was impossible.

Welcome to Project 3.18, a free weekly publication where a fan-first writer tells strange and surprising stories from baseball history and culture.

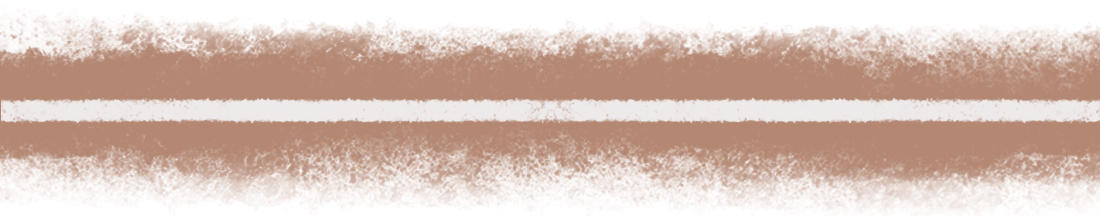

The last piece of the Washington Monument was put in place on December 6, 1884. After nearly four decades of on-and-off construction, this was a big moment—and a big piece:

Far below, a crowd had gathered around the base of the Egyptian-style obelisk, made of granite, marble, and a rock called bluestone gneiss (used mostly as filler). In the first of many things in this story that don’t sound safe to us, a number of invited guests were waiting in the upper interior of the monument while the Army Corps of Engineers team, under the direction of Colonel Thomas Casey, slowly lowered a 3300-pound pyramidion of stone into place from scaffolding that rose 40 feet above the height of the monument.

There was a hush while the team worked, easing the massive stone into its setting. When it was done to his satisfaction, Casey gave the signal. A large American flag was unfurled from the scaffolding to tell the crowd below that the deed was done. There were cheers and the sound of the 21 guns firing in celebration on the White House grounds to the north. Inside the structure, the guests began singing “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

There was more work to do before the monument would be fully ready for the public. The construction scaffolding inside and outside needed to be replaced with a permanent interior stairwell, and the steam-powered elevator that had been used to lift material up into the structure was going to be converted to ferry sightseers. But the builders had earned their 21-gun salute. They had persevered through design changes, budget shortfalls, bad marble, and even a short-lived hostile takeover by racists (really), but at least the monument now looked finished. The obelisk took its place in the record books as the tallest object human beings had ever built.

With that distinction, it would only take a few weeks for the first major league baseball player to look up at the Washington Monument and say to his buddies:

“You know, if somebody threw a ball from up there, I bet I could catch it.”

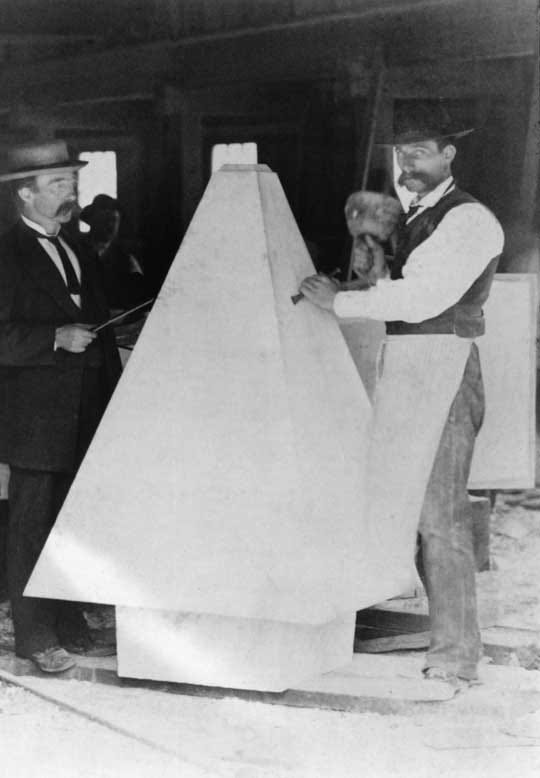

It all started in the offseason, when a young athlete’s boredom leads him down strange paths. In late December 1884, less than a month after the monument was structurally completed, a report in a Washington newspaper, the Evening Star, said that Paul Hines, “the famous baseball fielder,” had entered into a bet with P.H. McLaughlin1, the chief mechanic for the Washington Monument, that he could catch a ball thrown from the top. McLaughlin denied the report but had clearly done some thinking about it, saying he felt such a catch would be close to impossible. In later years Hines told a reporter that the original wager came from a sporting goods distributor, who apparently offered him (or any player, presumably) $200 if he could pull it off. Either way, Hines took the bet.

Perhaps this was inevitable. The monument was a wonder of the modern world; it was an easy commute from Washington’s Capitol Grounds ballpark; and, as we will see, it was quite accessible to the public. “It is probable that the Monument will be used for many tests as to falling bodies,” the Evening Star predicted. The paper said that a dropped baseball would take about 5.5 seconds to come down and according to some basic physical calculations it would be traveling at approximately 187 feet per second as it neared the ground.

That seemed like a lot of velocity, but ballplayers handled velocity every day. But, the paper cautioned its readers, “there are other matters to consider which would make the test more difficult.”

There was the height, of course. The Washington Monument measures 555 feet from the base to the top, and while that number is frequently attached to the distance a dropped ball would travel, no ball has ever been thrown from the tippy top, for self-evident reasons. After 1884 every catch attempt would utilize the windows in the monument’s observation deck. The observation deck is 504 feet up; add a few more feet for the windows.

The observation deck is still in use and the windows are still there—the ports are exactly the same as they were in 1884. What’s changed is that today the windows are entirely sealed and made from bulletproof glass. There are several very sad reasons for these changes and you can probably work out what they are. But back in Paul Hines’ day not only could the windows open, people frequently stuck their heads out for a better look.

From an 1888 article describing a visit to the monument, which was fully completed and opened to the public that year:

Some take off their hats and put their heads through the windows, exclaiming at the dwarfed appearance of the workmen on the mound below and then looking up toward the capstone, wondering at the multitude of lightning rod points which cover each of the four triangles of the roof. Then the heads are withdrawn with a sigh of relief.

A monument catch depended on a co-conspirator who could make the journey up to the 500-foot level with one or more baseballs and get uninterrupted access to the observation deck. And rather than stick out their heads, most of the droppers actually stood back, away from the open window, to sidearm-throw the baseballs out.

On January 9, 1885, Paul Hines and a few other players went out to the National Mall to see if one among them could make a little money and claim a little piece of offseason immortality to boot.

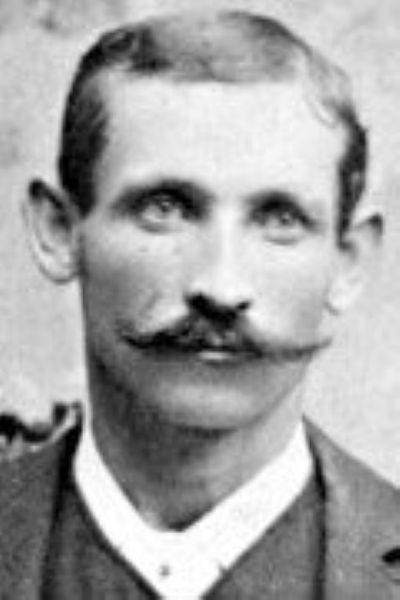

The party consisted of Hines, Phil Baker, Ed Yewell, a guy only identified as “Ryan,” and perhaps a few others not even worth mentioning at the time. Hines was, by far, the biggest name in the group. He played for several different Washington teams during his 20-year career, which spanned the period in which the National Association of Base Ball Players gave way to the “modern” National League. Hines seems to have mostly been an outfielder at the time of this story, when he was a member of the major-league Providence (Rhode Island) Grays.

According to Hines, at the time of their visit, “the monument was not finished, and the scaffolding built around the top rose higher than the monument itself.” The implication seems to be that in this instance the throws came from the scaffolding rather than out the windows, and therefore from even higher up than 555 feet.

The outfielder tried to pay some of the others to go up and throw the balls down but none were brave enough to risk the trip. Hines said he ended up paying one of the project workmen to do the throwing, giving him three baseballs.

No one quite knew what to expect once the balls started coming down. The basic math had been done, but nobody knew how a baseball traveling at that speed would interact with a player’s outstretched hands. Some believed the ball would be traveling not much harder than a “hot-shot” line drive, the kind infielders regularly had to field. Others thought the ball, if it hit the ground, would bore a hole in the earth like a drill. At that time there was really only one way to find out, but today we can make a sharper comparison.

On May 25, 2025, Pittsburgh Pirates outfielder Oneil Cruz broke the record for hardest-hit baseball (his own record, in fact). The scalded ball left PNC Park right away, seeking relief in the cool waters of the nearby Allegheny River.

The cameras couldn’t keep up, but StatCast equipment precisely tracked the ball’s exit velocity, which is defined as the speed the ball is traveling at the moment when it leaves the bat. The ball Cruz demolished had an exit velocity of 122.9 miles per hour.

A little math converts 122.9 miles per hour to 180 feet per second, just a touch slower than the speed of a ball thrown from the Washington Monument as it nears the ground. So basically what Hines and the others were trying to do was akin to fielding an Oneil Cruz smash—while standing just a few feet away from Oneil Cruz. Would you try that for 200 bucks?

Oh, and they may or may not have been wearing gloves. Secondhand accounts conflict on this point, but if Hines’ firsthand account takes primacy, they weren’t. “I had no gloves on,” he said. “We didn’t wear them then.” Even if some in the group did have gloves, they would not have provided anything like the protection offered by later versions; in 1884 the padded catcher’s mitt wasn’t even on the market.

The speed of the dropped balls was an anticipated concern, but once the worker started throwing them a new wrinkle appeared—the balls did not drop straight.

The rock face of the monument violently diverts the flow of air streaming over the earth’s surface, like a thumb being stuck into the stream of water coming out of a hose. As the air currents split every which way around the obelisk they create random and unpredictable drafts. These drafts grabbed hold of the ball and whipped it back and forth as it plummeted earthward.

The designated catcher waited a few dozen yards away from the monument, down a slope, looking up with the aid of the other players, who acted as spotters. There was a shout as a ball was released, tiny and grayish. “Here it comes!”

Hines said that when the ball shot into space far above him, “it appeared to be no bigger than a pea,” but as it got nearer to the ground it seemed to grow beyond its actual size. By the end it looked as large as a football.

The ball spiraled, veering back and forth in the roiling air. From above it looked like the player doing the catching was making a halting circle as he tried to keep in position underneath the erratic missile.

Imagine the concentration being put into that effort. Physically, optically, and mentally. Rock climbers probably know the feeling. Explosive ordinance technicians, too. Hines said it took the balls seven seconds to come down. It must have felt much longer.

Some tossed balls simply blew away. Hines said one landed on a shed and another in what he referred to as a nearby “lake.” It seems like the group had only brought three baseballs and so each contestant got about that many tries. Mostly the balls hit the ground with the players trailing a few yards behind.

Hines said that on his final attempt he actually made contact. He finished at a dead run and was able to use his outstretched hand (imagine it) to just get underneath the ball, “tipping the ends of my fingers.” He said the impact didn’t even sting as much as balls he’d caught in the outfield.

Another player, Phil Baker, did even better that day. Unlike Hines, Baker only hung around the edges of 19th century baseball for just a few years and then was gone. He played enough that we have his full name and a good picture of him, which is more than we have of Ed Yewell and other baseball shades found in modern records of these Washington teams, one-name, one-game-wonders like “Carroll,” “Franklin,” and “McRemer.” Baker wouldn’t even play in the upcoming 1885 season (Washington did not field a major-league team that year), but in the monument contest he almost got his hands on lasting fame.

Baker let the first throw land with a “whish and a thud” a yard in front of him. The dent it left seemed negligible. He tried again—another miss. Then he got ahold of one and somehow reeled it in. He held onto it long enough that the others began to cheer, but the January 10 account of what happened said Baker fumbled it at the last second, dropping the ball “almost immediately.”

If any other players took turns at catching, none came close enough to a ball to warrant a mention.

After that day the local authorities got wind of what had happened and made throwing anything off the monument illegal, with violators subject to a $500 fine, which in the 1880s was quite a lot of money. The Hines/Baker group does not seem to have tried again. Though they had come tantalizingly close, the players’ manmade Everest remained unconquered.

Did the new penalties stop everyone? Of course not. Every few years another brave fool would add their name to the list. Most of them, we must diplomatically note, were catchers. Not for nothing was catching equipment later labeled “the tools of ignorance,” and some of these ignorants had been willing to work as catchers for decades with little or no protection at all.

Tug Arundel. Jim “Deacon” McGuire. Charlie Snyder. Malachi Kittridge. Even the great Buck Ewing. All were said to have tried. None would ever be so bold as to claim they succeeded.

In 1892, success was declared, in newspapers in Washington and Cleveland, Ohio. Here is the entirety of that coverage, from the June 2 edition of the Evening Star:

Jack O’Connor of the Clevelands yesterday caught two of three balls dropped from the top of the Washington monument. This is the first time this has been done.

We’re calling “Pants-on-Fire” on this one.

“Rowdy Jack” O’Conner was playing for the Cleveland Spiders in 1892. And, yes, the Spiders were in Washington at the beginning of June, but after that the story is tissue-paper-thin. The details of every other recorded attempt suggest that making two monument catches in of just three tries is practically impossible.

Sure enough, two days later we get the retraction:

Jack O’Conner denies that he caught a ball dropped from the top of the Washington monument. Jack would rather be honest than famous.

It’s possible that O’Conner didn’t even know about the made-up story. Asked to describe the details of his feat, he incredulously said, “What did I do?”

The Evening Star had an itchy trigger finger when it came to reporting a successful catch. In August 1894 the paper declared that Bill “Pop” Schriver, catcher of the Chicago club (then called the Colts), had finally done it.

“I did not catch a ball thrown from the monument,” he told a writer two years later, in 1896. “I never said that I did. In fact I did not try to catch the ball.”

The broad strokes of Schriver’s story are archetypal. A bunch of bored players sitting around a D.C. hotel, talking with the hotel clerk, who wagered that there was “not a ballplayer in the crowd that could judge a ball thrown from the monument well enough to even get his hands under it.” Cap Anson, Chicago’s field manager, rose to answer the challenge and, being a manager, he delegated. Of course there was such a ballplayer, he said, pointing at Pop Schriver. Maybe the two didn’t get along.

Schriver said the wager was for $10, so it seems like the valuation for this life-threatening activity had crashed since 1884. He said that all he had to do to get paid was get properly under the ball, which he felt confident he could do. “Nothing was said about catching it.”

The next morning a crowd of young men went out to the monument, though Anson could not be bothered to make the trip. By this point the monument had been open to the public for six years, so the scaffolding was gone. The balls would be thrown out from the windows of the observation deck.

The thrower was to be pitcher Clark Griffith, who would one day manage and own Washington’s major league team. Griffith would wave a handkerchief out the window to signal a ball coming out.

Schriver had an additional advantage in that he seems to have been the first to attempt the catch wearing an early version of the oversized catching “mitt.”

“It didn’t seem to come down very fast,” Schriver said. “I could easily see it.” According to Schriver he got under a ball, satisfying the bet, and was even going to make a catch except he heard a shout from an angry police officer. The ball bounced off his gloved hand and he escaped the cop on foot.

Another player listening to Schriver tell the story interrupted him. Most of the details he was willing to buy, the part about the slow-footed Pop Schriver beating someone in a footrace was too much.

“You must remember,” Schriver said, “that I was running downhill.”

Having felt the ball land on his palm, Schriver was certain a true catch could be made, so long as the authorities were kept out of it. “A fellow can’t judge a ball five hundred feet in the air and keep an eye on the watchman at the same time. Any time I can get a bet and be given half a dozen trials, with no interference, I’ll be ready to post my money.”

By the end of the 19th century, the Washington Monument had welcomed hundreds of thousands of visitors and a steady stream of overconfident ballplayers, but after 16 years P.H. Laughlin’s initial prediction was standing as strong as the obelisk that bore his name. From the scrubs to the stars, nobody had made the catch. But protective equipment was improving all the while, and in the 20th century a new generation of catchers would come to the National Mall to take their shot. And not only would they be wearing armor, these guys would also bring a whole lot more ammunition.

Next week we’ll do our best to address the most pressing question in this story.

On February 2: “Where was the security?”

Over on Clear the Field:

Ted and I finished rummaging around in the baseball scrap metal drives during World War II. Here’s a tie-in fact for you—

America was so obsessed with funneling metal into the wartime supply chain that there was some serious talk about scrapping the aluminum capstone from the top of the Washington Monument. Cooler heads prevailed, but just the fact that this was discussed illustrates what a dangerous time the early 1940s for ornamental sculpture in the United States.

P.H. McLaughlin is one of four people involved in the monument’s construction whose name is inscribed into the 9-inch aluminum capstone that forms the point at the top. The capstone gives quite a lot of information, presumably so these essential details would be preserved even after the building crumbled. Strangely, however, George Washington is not mentioned.

Paul, if you ever again run a photo of someone clinging for survival from a ridiculous height (i.e., anything over 12 feet—15 at most), I swear to God I’m canceling my subscription and demanding a refund no matter how hilarious the caption is.

Love the detail about air currents making the ball spiral unpredictably, adding another layer beyond just velocity. Comparing it to an Oneil Cruz exit velocity really helps grasp what these guys attempted with zero gear. The Phil Baker moment,holding it just long enough for cheers before dropping it, feels archetypal for these almost-legendary sports moments that history nearly forgot.