Fire Watch

In 1993, Atlanta’s inflammable ballpark was burning, but nobody told the Braves to pause batting practice.

1965

To entice an established major league team to break ties and come south, the city of Atlanta promised a top-flight modern stadium (and an attractive lease). Perhaps because they’d already dared to relocate once already, the Milwaukee Braves (late of Boston), took the chance to trade up again, breaking Bud Selig’s heart in the process.

With the Braves packing their bags, Atlanta Stadium was built in twelve months across 1964 and 1965 for a taxpayer cost of $18 million. The park was ready in time for the 1965 season, but the Braves were held up by some spirited legal jousting up north, in which they agreed to play one last season in Milwaukee. In the meantime, Atlanta and Atlanta Stadium hosted the Beatles.

The modern multipurpose facility reflected the gold-standard for stadium development at the time, and the structure was entirely compliant with the 1948 fire code it was built under. Those aging regulations did not require a stadium to include water standpipes, which let fire hoses hook up inside a structure, nor did they require sprinklers. “The concern in those days was to provide exits for people to get out,” a fire marshal later said of the 1948 code, and so Atlanta Stadium had plenty of egress options.

1985

Now called Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, the facility underwent a major renovation, but the scope of the work was such that the structure remained exempt from newer 1979 fire codes that required automatic sprinklers in all buildings with three or more stories. Some experts wondered if the modernizing facility had run too far ahead of its dated safety infrastructure.

“The stadium is not the place it was envisioned to be in 1964,” a fire marshal said. “It’s not a place where you sell a few hot dogs, some popcorn and some Cokes. They’ve got a real mini-mall over there now, with a restaurant, a lot of carpets, draperies, and a lot of other flammable materials.” But still no sprinklers.

July 18, 1993

The Atlanta Braves took advantage of a “fire sale” in San Diego, acquiring slugging first baseman Fred McGriff in exchange for a package of three minor league players. Tired of being trade-bait, McGriff was relieved by the move, which put him closer to home in Tampa and paroled him off a club that was dead-last in the National League West. “I picked up a lot of ground on the Giants,” McGriff said of the trade. “I went from 20-something games behind to only nine.”

July 20, 1993 – 5:40 PM

McGriff’s debut helped sell out the night’s game against the St. Louis Cardinals. 49,072 tickets were sold.

As the park opened, staff and vendors readied the facilities for visitors. On the stadium’s second level, this work included setting up the various luxury suites that ringed the press and broadcast areas.

Local FM station WGST handled the Braves’ radio broadcasts, and part of that deal included the dedicated use of a luxury suite next to the radio booth. The suite was primarily used to treat the station’s corporate and business sponsors to a free night at the ballpark with all the trimmings. That night, an affiliated station, WPCH, was using the suite. Their honored guests, whoever they were, were to enjoy a meal catered by a local restaurant, Paisanos, and the catering staff busied themselves setting up the metal chafing dishes that would hold large pans of pre-cooked penne pasta and chicken, kept warm for grazing guests with small flaming containers of jellied denatured alcohol, commonly known by the name of a popular brand: Sterno.

5:49 PM

The dishes were set up, the cans of Sterno were lit, but at some point after that the entire catering staff exited the room, perhaps leaving briefly to retrieve supplies from the kitchen or a van parked nearby.

John Adams, a sports editor for the Knoxville News-Sentinel, arrived in the press box a few doors over, dropping his bag and what must have been a rather chunky laptop computer and heading down to the playing field, where the Braves were taking batting practice while the Cardinals filtered out of the clubhouse, preparing to take their turn.

5:53 PM

WGST radio announcer Matt Stewart delivered his last sports update of the hour in the broadcast booth. Switching off his microphone, Stewart looked up from his copy and noticed smoke blowing horizontally into his field of view. “The thing that impressed me was how quickly it just poured out and engulfed everything,” Stewart said. “It was a matter of minutes. It got heavier and darker, and within seconds flames were licking out.”

5:55 PM

A staff person, possibly a security guard, entered the broadcast booth, asking Stewart if the room had a fire extinguisher. It did not.

Pete Van Wieren, the Braves’ radio play-by-play announcer, was sitting in the press lounge, writing the lineups in his scorebook. “Someone burst in looking for a fire extinguisher,” Van Wieren said. “They opened the door and the whole thing filled with smoke. A huge cloud of black smoke came gushing in.”

Fans sitting in seats below saw someone with a fire extinguisher try leaning out from an adjacent suite to spray into the flames, but he quickly gave up. The window to use an extinguisher on this fire had closed.

5:56 PM

The Atlanta Fire Department received its first call about the fire at the stadium. An off-duty firefighter had tuned in to watch Fred McGriff’s introductory press conference, but instead saw fire footage shot by news crews inside the stadium awaiting that same conference. The firefighter called into AFD headquarters to ask how many units were responding. At that moment, he was the only one.

Park officials insisted that several staff and the switchboard operator did report the fire, but the 9-1-1 records showed those calls had come later–the off-duty fireman had been first.

5:58 PM

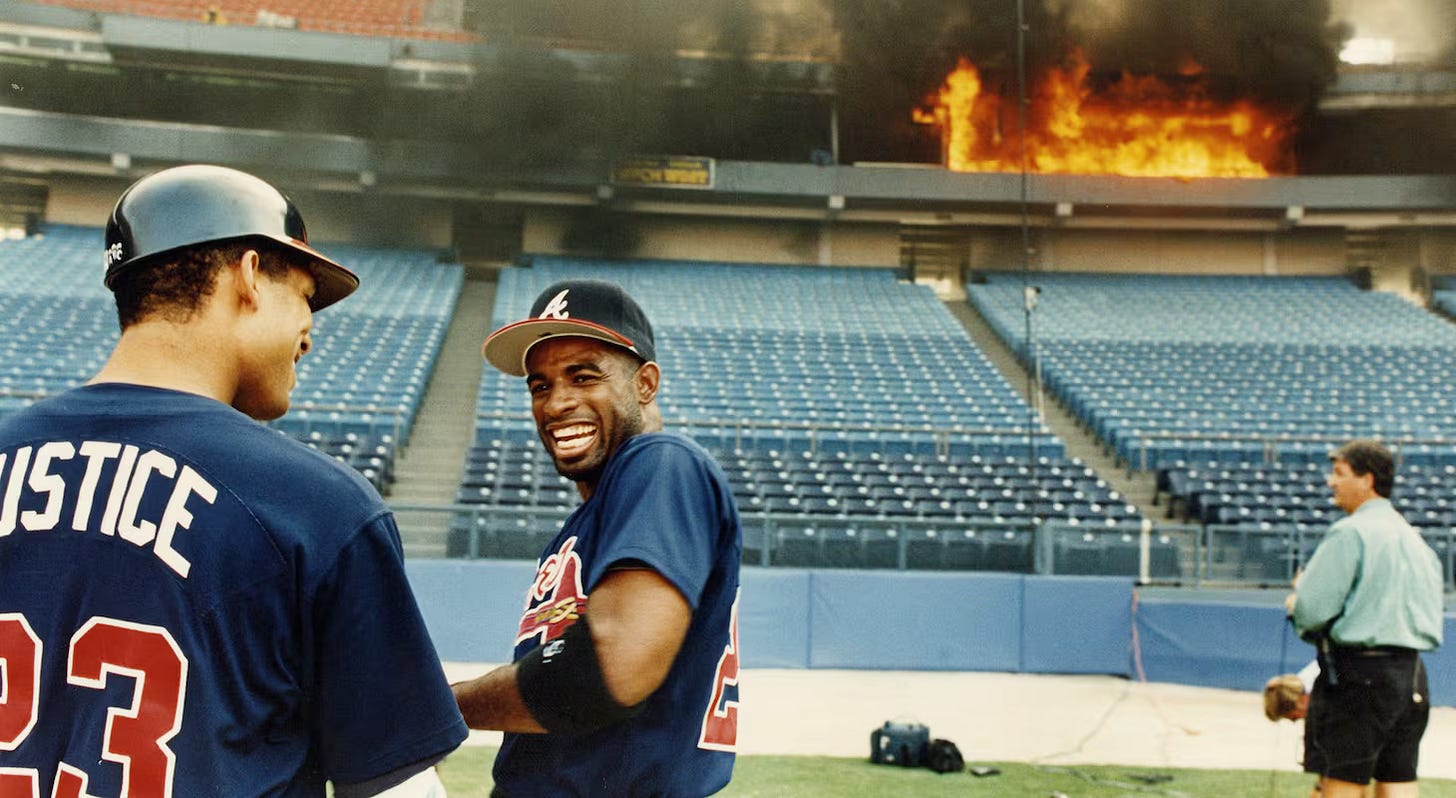

During batting practice, Fulton County Stadium’s natural turf field was littered with players, front office staff, and media. With so many loitering eyes, the players had been some of the first to spot the fire.

“At first I thought it was no big deal,” Cardinals first baseman Gregg Jefferies said, “but then I realized, ‘My God, that thing is going to be out of control.’” Jefferies and the other players could actually see that happening. “There was a ceiling fan in the suite,” he said. “Once the fan got a hold of the fire, it just started whipping it around. There were these curtains on the wall and they just went up like toilet paper.”

Furnace-like summer winds whipped the flames into the evacuated radio broadcast box, with the press areas next in line. Jefferies and several other players began yelling up to the press box to warn them of the danger nearby,

“We were all down around home plate,” Braves center fielder Otis Nixon said, “still doing batting practice, and looking up at the fire and wondering when someone was going to put it out.”

The line between someone else’s problem and everyone’s emergency can be hard to discern. A very serious fire was burning a few dozen feet above their heads, but the Braves’ batting practice—for the moment—continued. No one had told them to stop, so they didn’t.

Nearby, Ted Turner, the team’s owner, was cracking odd jokes. “I hope this is an omen that the Braves will get hot,” Turner told a reporter, who dutifully wrote that down. The owner looked up at the as-yet uncontested fire and grew somber. “We sure could use some water in here,” he said. “I know there’s plenty of it over in the Mississippi.” The Mississippi River was, at its nearest point, some 370 miles away.

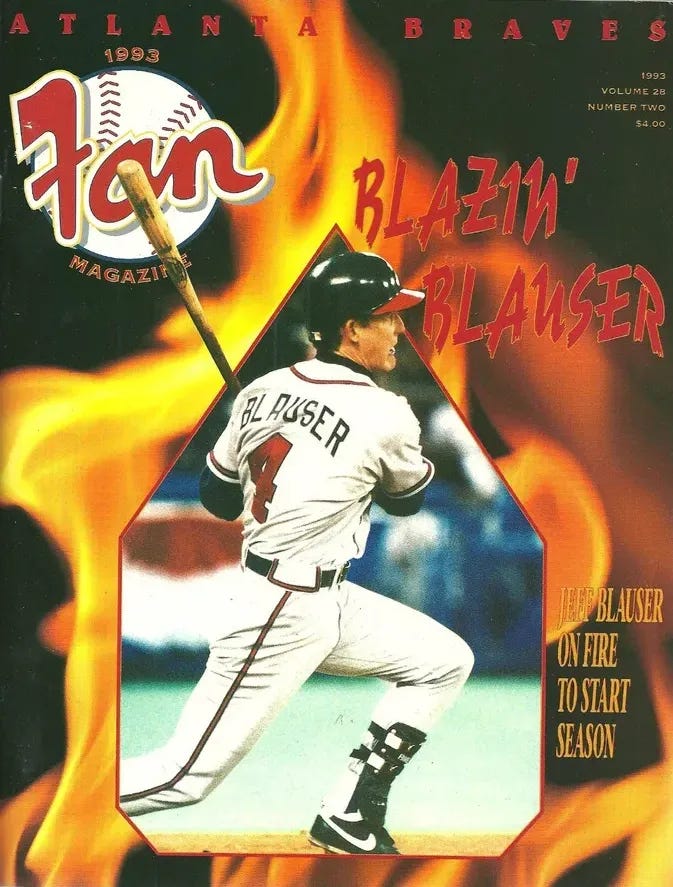

People adapted their usual routines to the unexpected situation. Program vendors roaming through the seats were unexpectedly cleaning up. “Get it while it’s hot!” they shouted. The $4 program being distributed that night:

Asked later what employees were trained to do in an emergency, one vendor said he didn’t know, and the thought of a serious fire had never crossed his mind. “I didn’t think this place could burn,” he said. “It’s steel and concrete.” Alas, the drapes, carpets, and tabletops were fabric.

The fire “spread like a blow torch,” said fire department chief Dave Chamberlin. Atlanta was in the throes of a record heat wave, and the early-evening temperatures were still above 90 degrees. Warm currents swirled in the park’s upper levels, pulling the fire from one box to another.

Seeing the fire burning toward their headquarters, some of the writers on the field made a wild dash back up, hoping to save their laptops.

On the foolish notion that we should try to rescue our portable computers, a group of us hurried upstairs from the clubhouse. We were met by insistent security people and a solid wall of dark smoke. Here came [TV broadcaster] Skip Caray and his son, Josh, their eyes red and watering. “The scary thing was the smoke,” Caray told us. “By the time we left the press box, we couldn’t see. You had to feel your way out.”

The reporters wisely followed the Carays down and left the laptops to their fate.

6:02 PM

A four-alarm fire was called, summoning units from fire stations throughout the city. The first responders arrived approximately six minutes after the fire was reported, and over the course of the next hour the total force grew to include a hundred firefighters from 25 units, 11 engines, seven support trucks, three commanders, two rescue units, a helicopter, and a hazardous chemicals team.

The firefighters confronted a situation with pros and cons. On the plus side, the stadium was mostly empty and there was plenty of room for them to work. Chamberlin said that if the park had been full, officials would have called a five-alarm fire, the highest-level emergency. “We were rather fortunate we did not have to go through exiting crowds.”

On the minus side, Chamberlin said, was the fact that, “in this particular case, the closest water source that we had was in a pumper truck outside the building. So we had to lay line from there to the fire area, and that’s a rather significant task.”

“Laying line,” meant stringing 500 feet of heavy firehouse from trucks outside the stadium, which fully-dressed firefighters had to manhandle up the interior ramps in the stifling summer heat. “We had to run 100 feet one way and then 100 feet the other way to get up to the next level,” one firefighter said. Some of the sympathetic stadium employees donated golf carts to speed the crews along.

6:10 PM

“I was in the clubhouse when a security guy came in and said to evacuate because there was a fire in the press box,” Cardinals manager Joe Torre said. “By the time I got to the dugout, it was raging.”

“This is a first,” said Fred McGriff. He had been in a batting cage under the stadium when the fire started, but the lower levels were evacuated onto the field. “All I know is they told me there was a fire, so I got out of there.”

By now a wide swath of the club level was on fire, the flames pushing further down the row of luxury suites. The suite assigned to Braves president Stan Kasten and general manager John Schuerholz was fully consumed.

The players continued to gawk, the seriousness of the situation still unclear even as burning debris began to drift down into the seating sections below the fire. Those sections were being evacuated by ushers but no general evacuation order had been given and thousands remained in their seats.

Fans and players stood watching and wondering at the surreal and quietly thrilling sight. Cardinals shortstop Ozzie Smith gave a summation worthy of Yogi Berra: “You think you’ve seen it all, and then you realize you haven’t.”

And then something blew up.

“It sounded like a beer keg,” the Cardinals’ trainer said of the explosion. “Or a bomb.”

“You could feel it down in the training room,” Braves trainer Paul Wolkoff said. “That’s three levels down from club level, and the walls started to shake.”

“It scared the hell out of me,” Torre said. “Everyone was running for cover.”

Television sports reporters abruptly wrapped up their live coverage, players known for their sprint speed ran, and some not known for their sprint speed surprised themselves and those around them. “I ran,” Braves coach Pat Corrales said. “I thought my ankle was bothering me until then.”

“The next thing I knew everyone went into a 60-yard dash to the outfield,” Otis Nixon said, “including [Braves manager] Bobby Cox. I didn’t know Bobby could run until a few minutes ago.”

But even after the explosion, some people working inside the facility still didn’t even know what was happening. “I thought it was fireworks when I heard the explosion, so I kept selling my souvenirs,” one vendor said. During a game the previous week, post-victory fireworks had accidentally been set off early, and now some people figured similarly itchy trigger fingers had led to the evident smoke and commotion.

The true cause of the explosion was a large steel girder supporting the third deck, superheated by the fire to the point that it warped and possibly ruptured, releasing a lot of tension and noise in the process.

After the bang, fire officials finally ordered the Braves to evacuate the seating areas, but the players were left unbothered, and for lack of anywhere to go, both teams stood in the outfield for another hour as five fire trucks were brought into the infield to try another angle of attack. Stuck there with a bunch of reporters, photographers, and camera-people, the players mugged for posterity. Fred McGriff did an ad hoc version of his press conference.

“There is no manual for proper procedure during a fire delay,” Adams, the sports editor said, reflecting on how everyone had spent that time. “You had to wing it.“

6:17 PM

The fire department got the first water on the fire. A few minutes later gates opened to allow trucks out on the field, and the volume of water fighting the flames increased as three dozen firemen sprayed up from home plate into the flaming concrete vaults above.

One firefighter was subsequently transported to a nearby hospital with chest pain and symptoms of heat exhaustion. Ten others were treated on-site, felled not by the flames, but by the ferocious Georgia summer. It was an unfortunate fact of their work, Chamberlin said, “that there is not a fire hydrant in every square foot of this city.” He guessed that if the park had included standpipes, the fire would have been out five minutes after his first crew arrived.

6:45 PM

It took 30 minutes to bring the fire under control and another 15 to extinguish it, but the fire was finally put out.

6:50 PM

Refugees from inside the park had joined thousands more arriving outside, seeking any kind of shelter on the pavement, where temperatures neared 100 degrees. It might have been cooler near the fire. They waited for news on the fate of the game.

7:00 PM

Officials from the fire department and building code toured the still-smoking, damaged areas, but quickly deemed the large majority of the stadium safe for use. Fire-damaged seats across six aisles at field level and the same aisles in the upper deck (above the damaged girder) were roped off; fans with tickets for those areas were assisted in finding open seats elsewhere.

The stadium’s radio booth was burned out, and there was minor damage to the press areas and the Video Matrix scoreboard control room. The scoreboard worked, as did the lights, but the public address system was offline.

The Braves announced that the game would start at 9:40 PM.

“There is a general ethic in baseball to always play the game,” Stan Kasten said. “There’s really no reason not to play. This is on the order of a good, hard rain delay.”

Joe Torre was not surprised by the Braves’ determination. “They may have to trade [McGriff] if they lose the gate.”

7:40 PM

The firefighters were the night’s heroes, but coming in a (distant) second were the TBS and WGST production crews.

The television broadcast booth was intact, but temporarily inhospitable. “The smell, the ashes, and the soot made it unworkable,” a TBS executive said. “You could only be in there a couple of minutes before you were overcome by the smell.”

The TV broadcasters, Skip Caray and Joe Simpson, were relocated to a table positioned along the right field line. They went on the air to explain the situation as the game went into delay.

“We’ll have another night of something,” Caray promised, “but we’re not sure what.” It was an explanation that would have made his father, Harry Caray, proud. He and Simpson talked about the fire and threw to radio announcer Pete Van Wieren, who interviewed Schuerholz, the general manager, on the same subject. Then TBS went to rain-delay coverage, showing a repeat of This Week in Baseball and then reruns of All in the Family.

When the game started, radio listeners were able to get the piggybacked audio from the TV broadcast, but WGST’s crew worked feverishly until they found a way to broadcast over a phone line. By the fourth inning, Pete Van Wieren and Don Sutton were on the air.

9:00 PM

Before the game started, Van Wieren made his way back up to the press box, which had suffered smoke and water damage. The announcer hoped to recover the remains of his scorebook, a valued companion he’d had to leave behind. To his delight he found it untouched by the night’s various forces of destruction:

I looked over to where I was sitting—and there was the scorebook, clean as a whistle. Well, I had to blow some dust off the coils, but otherwise it was good as new.

9:38 PM

30,000 half-cooked fans cheered as the Braves’ Tom Glavine threw the first pitch, ending a good, hard fire delay.

That was a big boom.

This week we’re heading to Dallas to present at the Society of American Baseball Researchers national conference. And while our brains are mostly steeping in the weird Victorian world of catcher Billy Earle, we’ve been saving a few more modern gems to share and we’ll have those polished and ready for you next Monday.

On June 30: Postscripts: Parties, Pilfering, and a Little Garden

The Braves handed out commemorative bobble heads in 2023 featuring Ron Grant striking a pose in front of a flaming press box.

This is the best and most comprehensive write-up I've seen on this story. And I'm not surprised in the least. Excellent work, Paul.

As an Atlanta resident, I remember this and I found the minute by minute account fascinating, Paul. The photo of Glavine was epic and how I remember him, even though he still is a sometimes commentator on FanDuel Network broadcasts of Braves games. And Fred McGriff, the “Crime Dog!” Ron Gant, David Justice, Otis Nixon, Jeff Blauser … names that are a blast from the past. Thanks for the deep dive into this story.