Ken's Way

A beginning and an ending, then an ending and a beginning.

Some numbers on Ken Holtzman, in no particular order:

Win/loss record of 174-150 across his 15 year career in the majors

127 complete games

6-4 postseason record across 13 starts, with a 2.30 postseason ERA

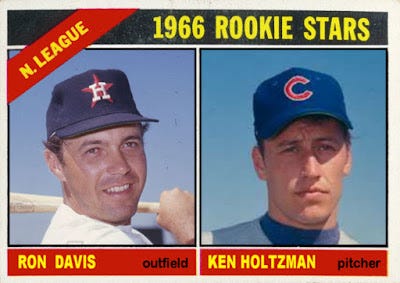

Drafted in the fourth round of the inaugural amateur draft in 1965

9 years with the Chicago Cubs

4 years with the Oakland A’s

3 Years with the New York Yankees

2 All-Star Game appearances, which is really low; he should have been in at least two more

4 World Series Championships

Wore number 30 whenever possible

2 no-hitters

And in 2024:

Became the first professional baseball player I interviewed

I first got in touch with Ken Holtzman via old-fashioned networking: a former co-worker was good friends with one of Ken’s children, and after I started Project 3.18, she saw what I was up to these days and kindly offered to try and connect us.

She warned me it was not a sure thing, however, because:

Sometimes he’s willing to participate in baseball opportunities like interviews or reunions, and sometimes not.

I thanked everybody for trying, wondered at the thought of being a “baseball opportunity,” and waited to hear back. Ken’s daughter thought he’d enjoy it, and worked her magic:

Well, good news! My dad said he would be happy to talk to Paul…

Though there was a catch:

...by email only. I knew he would say that. But he answers email quickly.

So, the response was overall good, but that proviso did require me to have to shift my thinking a little bit.

When I first imagined talking to Ken, sure, I got carried away. If he said yes, I’d make my way to his hometown of St. Louis to spend parts of several days seated in his tastefully-appointed baseball study, looking at various awards, black-and-white photos, and framed clippings on the wall while the actual real-life person who generated all those plaudits sat in a large overstuffed leather chair and talked all about it all. The first night I’d stay at a motel but the second night he’d put me up in a spare room. It would of course become the definitive interview of his life. And when we were done he’d give me a ball signed by the entire starting rotation of the 1972 World Champion Oakland A’s that he just happened to have sitting out on his desk, and say, “Hey, Blue Moon Odom’s phone number is on that, you should talk to him, too, tell him ‘Kenny sent you’” and…

Of course, the rational part of me understood how nice it was that he would talk to me (who?) at all. Email it would be! To make the most of the opportunity, I researched the best practices for email interviews, and I will now sum these up for you via the one piece of advice I found most salient:

“Ideally,” the literature says, “do not do email interviews.” And that really is good advice.

Of course, anyone who can work in paragraphs and likes to tell stories and types fast can be a great email interview. For example, I think many writers would be great subjects for email interviews (*pointedly clears throat*).

But, see, here’s the thing: Not everybody communicates that way. Some people are To. The. Point. And those people can give great interviews, too, but only if you can work with them in real-time conversation, because they just aren’t going to conjure up four paragraphs of anecdote-rich reflection and put a bow on that for you. You have to get them there. Think about it like curling. You need to be ahead of them with the little broom things, nudging the big rock thing in the right direction. Apologies for all the technical curling terminology there.

With Ken, at first I didn’t really know what kind of email interview subject he was, because this was the sports history equivalent of a blind date.

And let me not risk underselling the extreme generosity Ken showed in being willing to connect with me at all, in any medium. I was Just Some Guy, maybe Just Another Guy, at best. I had no credentials, no bona fides; I’m not even sure I had my Society of American Baseball Researchers membership at that point. I could have been a weirdo. For all Ken knew, I might have wanted to ask him about what kind of socks he wore as a player and whether he still had any of them. But God bless this man, for whatever reason, he agreed to show up at the metaphorical restaurant.

Going in, I didn’t even what to call him. He didn’t really have a nickname that I could uncover, and honestly that seemed right. I asked him about this, near the end of our correspondence, and he said, “Aside from some private nicknames, I’ve always been Kenny to most of the players.”

This was a quintessential “Ken” answer in how it provided some information while also keeping up an air of profound, tantalizing mystery. Somebody out there called him “Shooter,” I just know it…

For my part, I ended up too scared to do any version of his given name and just rolled with “Mr. Holtzman.” Writing about him now, I’m splitting the difference with “Ken.”

When I first contacted him, I wanted to demonstrate that I was prepared and capable of asking thoughtful questions on appropriate subjects. My first set of questions generally pertained to the events covered in The Break-Up, as well as the no-hitter Ken pitched against the Atlanta Braves in 1969.

One other thing my email interview research impressed upon me was the need to ask follow ups in subsequent messages, and the importance of laying that groundwork right away.

And so as I wrapped up my questions, I asked the most important question, in my view: Would it be all right if I ask you some additional questions, depending on your responses to these?

I read the whole draft about six times, obsessing at the word-level, certain that any imprecise use of a or an would expose me as a pretender. And God forbid I get a date wrong, like a child would. When it was finally perfect, I got up and walked away because I was still too nervous to send it. I remember the next day when I sat at my dining room table with my cursor hovering over the “Send” button, trying to find any additional reason to delay, without success. It was time to begin something new in my life, something I really wanted to do, and Ken had opened a door. I clicked the button and realized I’d been holding my breath. It was 9:30am.

I exhaled and began what was surely going to be several days of waiting as Ken read everything I’d ever written, carefully assessing my worth as a scribe. If I passed the test, he’d begin answering the rich, open-ended, prompt-like questions that I’d sent him, probably doing one a day, perhaps finding some delightful photos or other ephemera and sending them along as jpeg files, cc’ing old friends and comrades from the 1969 Cubs: “Hey Paul, adding Fergie here. Fergie—tell Paul that secret nickname you gave me…”

Ken’s actual response came at 3:32pm—the same day. And when I saw it sitting there in my inbox, I thought about it like lawyers do when they hear the jury has come back much more quickly than expected: this means something, but what?

The verdict was in: Ken was willing to answer my questions!

Not that he said so. He just did it. He Answered. The. Questions.

No greeting. Not a word of pleasantries, no extemporaneity of any kind. Not so much as a closing salutation, not even a minimalist “kh” under the body. Ken’s message consisted wholly and entirely of the answer to my first question. A few minutes later, another email, with a response to another question, and a few minutes later, a third. I think Ken skipped two of the questions I’d asked that day (which is another big reason the best practice with email interviews is to not do them).

Ken did answer that all-important last question, though, the one where I wished for more wishes:

KH: Email me with more questions and I will try to remember as much as I can.

And just like that I had an enigmatic baseball pen-pal, for as long as I could keep up with him.

We completed ten ask-and-response sessions between February 12 and March 5. I usually let a few days go between each exchange, but never too many, because I didn’t want him to think I was getting bored. I ended up needing the days to figure out more and increasingly-afield questions.

Every exchange began with, “Dear Mr. Holtzman,” because he never said, “Call me Ken” (too extraneous) and they all ended with me saying, “Thank you very much.”

As we went on, I included true follow-up questions, based on what he’d said last time, while also putting out a few new lines. Sometimes he bit, sometimes he didn’t. We started with the 1969 Cubs, moved on to his remarkable run of pennants and titles in Oakland in the first half of the 1970s, and did a little bit on his twilight years in the Bronx Zoo and his return to the Cubs to finish his career. We talked about his pre- and post-baseball life some. We spent bonus time on his role in baseball’s labor movement and the movement in general—this subject meant a lot to him and I am very interested in it, too.

And I worked on him, man did I work on him. I tried to warm that guy up every way I could within the constraints of the medium. I did my homework, I stuck to his preferred subjects, I sent him videos of himself and asked him to talk about them. I reacted to his responses in my messages so he could appreciate my genuine delight and interest. I mentioned bits of my biography and things we had in common.

But my sense of Ken is that he was a man of great personal discipline, and his responses inevitably followed a pattern:

Answer the same day

No conversation

Separate emails for individual questions

Be. To. The. Point.

No “and-another-thing”-ing: answer what you are asked

Here’s a marvelous example that tee’s up next week’s piece:

P318: After your August 19,1969 no-hitter at Wrigley Field, a number of people from the packed stands jumped over the walls and came out onto the field as you celebrated with your teammates. Not really something modern players have to worry about! At the time, you even said that a fan had come up and choked you.

What do you remember about the end of that game, the celebration, and what happened when fans came out of the stands?

KH: I remember Hank Aaron made the last out and [Cubs third baseman Ron] Santo jumping on me. After that I was surrounded and choked by dozens of fans.

That is the kind of answer you’re supposed to give opposing counsel in a deposition!

This exchange and subsequent efforts to wheedle thoughts and feelings out of Ken led me to a greater appreciation for how important internal details are to creating meaningful narrative in sports stories. I don’t just want to see someone throw a no-hitter, I want to know what it felt like. And this guy knew. Even decades later, he still knew. The physical gifts were gone, but the memories of what he’d done with them were still there.

For a man of 78, Ken had a pretty darn good memory of things that happened to him more than 50 years ago—certainly the big moments like his no-hitter, but also some of the smaller ones. That was impressive, but more impressive, if complicating, was his ability to deliver a saga in a single succinct sentence. That no-hitter answer is a marvel of brevity. Truly, he didn’t leave anything out. As you’ll see when we get into it, he conveyed all the key components of that moment—a moment that he told reporters at the time was the pinnacle of his lived-experience—in 28 words. And I added four of the words, for clarity!

There was no meandering with this man. He wrote in purposeful, efficient strides. If it were me, and I started Game 4 of the 1974 World Series for the A’s and pitched 7 and ⅔ strong innings and—a full year after my league took the bat right out of my hands—I hit a home run, rest assured I would find a way to work that in.

It turns out, not everyone is a great storyteller, no matter how many great stories they have to tell. I’m not sure I understood that these things exist on separate tracks, but now I do. Sometimes they converge in the same person, and it’s brilliant when that happens, but often they don’t. Ken got all the substance but not as much of the flash.

But the fact is, Ken Holtzman was a lodestone in a fascinating time of change in baseball and he excelled at levels even many pros can only dream of. His story is almost uncannily the story of his era, from the first draft to the first free agency, with stops in the Cubs’ heyday, the Swingin’ A’s, and Billy Martin’s first Yankees, and while most of us would prefer those stories in more than 20 words, with Ken, it took how many it took and not one more. He did the pitching. Somebody else can do the stories.

By March 5 our exchanges had circled Ken’s life and then some. There was a period in the middle where he’d started to loosen up and open up a little, but by early March his answers, not long to begin with, were getting shorter, and he was replying to fewer of my questions per email. I didn’t know if he was losing interest or if I’d overstayed my welcome in his inbox, though either would have been fair. For my part, if I wanted to keep up the quality of my questions, I’d need to regroup. I wrote him one last time to thank him and wrap up, at least for the moment.

One of the few personal things we established in our correspondence was that Ken had family and grandchildren in the Chicago area and came up my way from time to time. In my last message, I nearly begged him to tell me when would be here so I could take him out to lunch to thank him in person. I said we could go to a place around the corner from wherever he was, make it super-easy. I’d love to meet you, Ken, after this fascinating and surreal blitz we just did through your life and times.

He did not respond to that email, which did not surprise or trouble me one bit. That was Ken’s way, at least it was his way with me in our work together. I had said what I wanted to say to him and I knew he’d read it. And hopefully I’d hear from him again.

I don’t know the exact timeline or details beyond what has been publicly shared, but about three or four weeks after I sent that last unanswered plea for future sandwiches, Ken went into the hospital for treatment related to his heart, and on April 15, the friend who first put us in touch wrote to tell me Ken had passed away overnight, at age 78. That morning, I wrote something to mark his passing, but it took me a few more days to realize it was very possible that the first player I interviewed gave his last interview to me.

Ken was not a boastful man, but he’d seen and done some things worth boasting about. I’d hoped to start writing some of Ken’s stories and then go back to have him fill in some specific blanks. In the wake of his passing I decided to proceed, taking some of the episodes he’d touched on with startling, almost appallingly-funny matter-of-factness (and some episodes that he skipped over even when I asked) and give those deserving stories the real Project 3.18 treatment, including his words, then and now, whenever I could.

And though I can’t hope to compete with his word count efficacy, when we’re done, everyone around here will know all about Ken Holtzman, what he did, and what he thought about it (as much as I can puzzle that out).

But I wanted to start with this story where I had all the pieces: of a reserved, precise, and generous man who took me seriously when there was no real reason to do that and then outlasted me in a three-week email interview. Your ranking may vary, but on my list of Ken’s accomplishments, that goes at the top.

Next week, in our first dip into a storied life, we’re going to revisit that August 19, 1969 Wrigley Field no-hitter and with a little help from Kens young and old, we’ll uncover how it feels to stand on the mound with the game, the season, and your entire reputation on the line. Oh, and he just got a new catcher because the guy who caught the first eight innings just broke his hand.

On July 1: “The Last Out”

Paul, please keep up the good works. Your stories take me away from my problems and those of the world. Isn't that what baseball was always about?

My 2c worth says no hitters were just as rare.

Brilliant.