One Last Pitch - Part 2 of 2

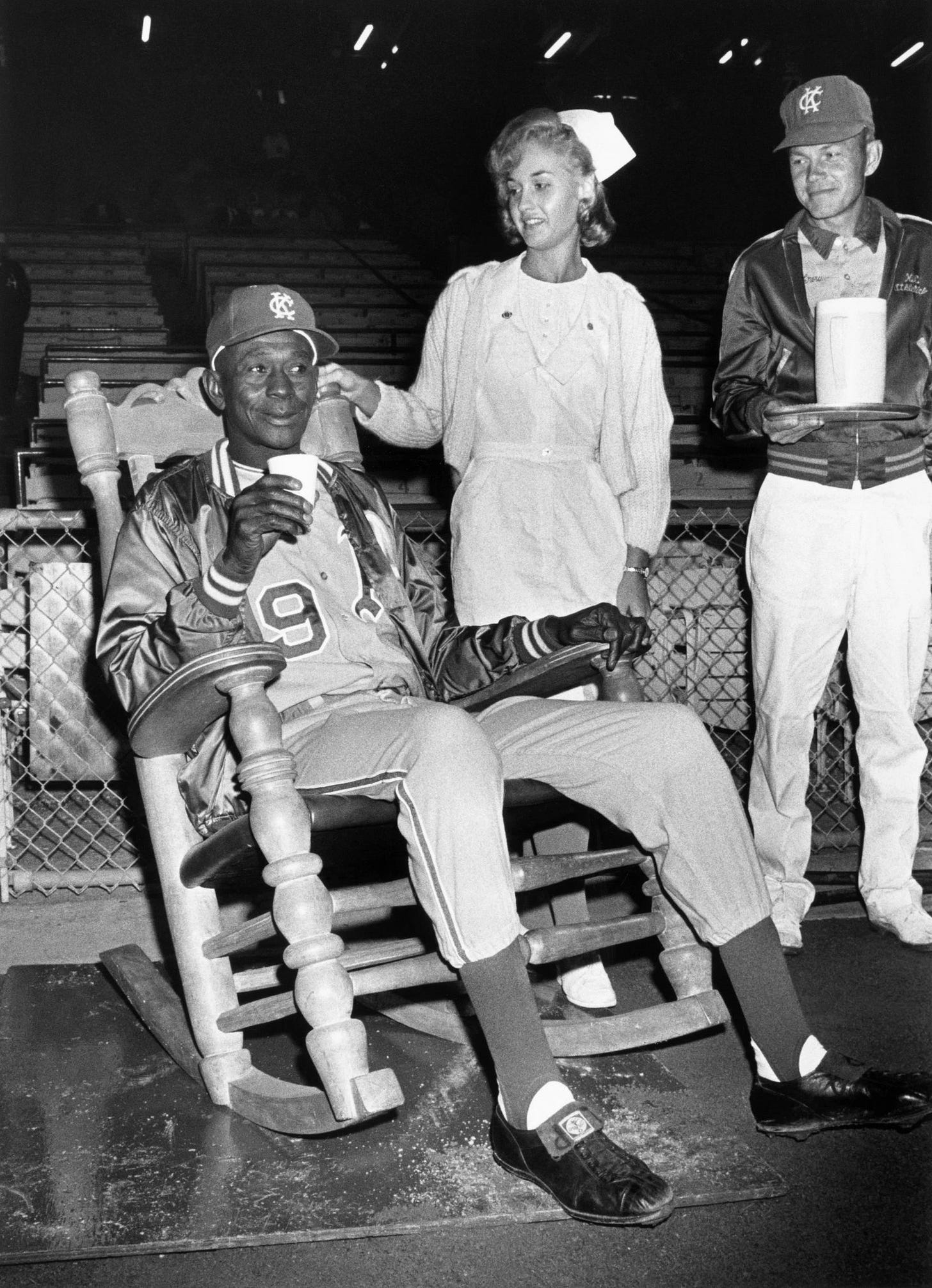

When he left his rocking chair, fans in Kansas City gave Satchel Paige a rock-star reception.

This is the conclusion of the story of Satchel Paige’s time with the Kansas City A’s in 1965.

Here’s Part 1, if you missed it.

Satchel Paige joined the A’s in Minneapolis on September 15, 1965. His oversized, reupholstered rocker met him there, and he amiably settled in, remaining still and statuesque as a different generation of men played his game.

He participated in the team’s warm-ups and workouts to the extent that he wanted, and he showed his longstanding antipathy to calisthenics. Pitcher John O’Donoghue, age 25, asked Paige if he would run with the team. “You got any other jokes?” Paige replied.

But he did pitch in the bullpen before games, and fans in Boston got a chance to see what he still had when the A’s played a series there. One of these curious spectators made sure to write The Sporting News to testify to what he saw:

When Satch started loosening up I went over to watch. I was astonished. He showed a hopping fastball and two changes, the hesitation and the regular.

I was also curious to see if Paige really warmed up over a bubblegum wrapper as I had read. As I looked down into the bullpen, I saw that a wrapper was actually there.

Preserved and passed down in stories, many of Paige’s deeds had prematurely become legend, but there he was, still standing 6’ 3”, still weighing a sinewy 180-some pounds, his muscular right arm slinging a baseball right over the top of a gum wrapper set on home plate. What year was it? What decade was it?

On September 21 the A’s were back in Kansas City for their final homestand of the year, and fans at Municipal Stadium got their first good look at Paige in an A’s uniform. It quickly became clear that Paige was not going to be used prior to his September 25 start. He spent the games in his rocker next to the bullpen, a living exhibition that would have earned P.T. Barnum’s approval. The chance to see the greatest living pitcher do an impression of a wax statue hadn’t sold many tickets. With an ocean of empty seats behind him, Paige could look directly across the field and see Finley’s mule, Charlie O, performing a similar function.

The nights were growing cooler in Kansas City, the A’s were nearing 100 losses, and football season was underway. On September 23 the A’s won a walk-off 8-7 victory over the Washington Senators in front of just 690 fans. It was so quiet during the course of that game that the avian residents of the A’s zoo out beyond left field did most of the cheering.

He wasn’t doing any pitching, but between games Paige was treating the other A’s, young enough to be his children, to a singular experience. It was as if Babe Ruth had walked into the clubhouse and asked to borrow somebody’s bat.

Paige was used to the reception he got walking out of the proverbial cornfields and onto ball fields all over the continent. He was cool and professional and kept quiet until someone approached him to talk. He was friendly and remained one of the most charming personalities in sports, and once he got started, the old stories came tumbling out. Rene Lachemann, who acted as Paige’s bullpen catcher, recalled Paige telling him a story about Josh Gibson, the great power hitter of the Negro Leagues and in many ways Saige’s counterpart. Gibson, Paige said, had once hit a ball over the fence and it travelled 500 miles.

“You mean 500 feet,” the catcher said.

“No, son, I mean 500 miles.” Paige explained that there was a railyard behind the ballpark in Mobile and Gibson’s ball dropped into a moving train car bound for Birmingham. Birmingham, we should say, is only 250-some miles from Mobile, but this was still the furthest-traveling home run in history by a wide margin.

He had a thousand stories like that, and even if they weren’t true, they helped preserve the legacy of the Negro Leagues. Many of the greats Paige played with and against, including Gibson, were already gone and unable to tell their own stories. Paige brought them back in a way the young A’s would never forget.

The ninth-place Red Sox would be Paige’s opponent on September 25. On September 24 Boston arrived in Kansas City and ran into 19-year-old rookie Jim “Catfish” Hunter, who carved them up over the course of a complete game shutout, escaping a no-hitter only in the seventh when Carl Yastrzemski, tied for the league lead in doubles, hit another one. A night later the Red Sox would face an opponent a half-century older.

Boston held a team meeting to discuss their strategy against a living legend. The manager, Billy Herman, encouraged the players to look out for Paige’s well-being and “try not to hit up the middle.”

Infielder Rico Petrocelli recalled the team’s feeling that Paige’s appearance was a gimmick. They didn’t want to embarrass Paige and they weren’t concerned about embarrassing themselves.

Charles Finley, the A’s owner, made a rare trip to Kansas City for the occasion, leaving the fortress headquarters of the Finley Insurance Company in a Chicago skyscraper to see the best player he’d ever put in an A’s uniform.

Finley had continued putting little touches on the spectacle, but these increasingly departed from Bill Veeck’s trademark satire and cheeky surrealism in favor of the coarser brand of humor Finley himself found enjoyable. To ensure his aged starter was well taken care of, Finley assigned him both his own water boy and, more notably, a real, practicing nurse, whom an A’s representative had spotted in a store. Her job was to wear her white uniform, cap and all, and “keep Paige comfortable.” No one knew what that meant so the nurse mostly just stood in the seats behind Paige’s rocker and hovered. Photos were duly taken but Paige saw the nurse as a bit much and kept his distance.

Other gestures were classier, reflecting sincere appreciation for Paige, what he’d done for baseball, and the institution of the Negro Leagues in which he’d shined.

Many family and friends were in the audience that night, but not his wife, Lahoma, soon to give birth to the couple’s seventh child. His six other children were present, and Finley sent them home with a bouquet of roses for their mother.

An even nicer touch happened before the game, showcasing a star-studded contingent of retired Negro League players from the Kansas City Blues and the Kansas City Monarchs, whom Paige had helped win four pennants. The players, including Cool Papa Bell, Buck O’Neil, and Bullet Joe Rogan, played a brief old timers game for early arriving fans. This was a true bit of showmanship by Finley—all these greats had been retired for at least a decade, creating a stark contrast to the one amongst their fraternity who, somehow, was not.

And while the crowd of 9,200 didn’t reach the levels of Farmers Night or even Campy Campaneris Night, at the tail-end of a tail-end-season, the promotion brought in more fans than the five prior games combined.

As Paige finished warming up before the game, the A’s turned out the lights in the park and fans lit matches and sparked their pocket lighters. A spotlight was turned on to highlight the night’s starter and the announcer said, “Kansas City’s own Satchel Paige!” Just under 10,000 people made enough noise for twice that number. “The place just went goofy,” one of Paige’s teammates remembered.

Lachemann finished warming the pitcher up. “Satch, you loose?” he asked.

“I’ll be loose when I’m ready,” Paige replied. Lachemann didn’t know what that meant but the sting in his hand when Paige fired him one last fastball answered his question.

Wayne Causey, the A’s third baseman, recalled playing “as deep as I could get” that night. He was afraid the Red Sox were going to tee off against Paige and send scalded balls in his direction. Another teammate remembered thinking Paige wouldn’t last an inning. “I didn’t know if he could reach home plate.”

The Red Sox centerfielder, Jim Gosger, was the only hitter who got to face Paige twice, including the first at-bat of the game. Gosger fouled out to the first baseman.

“He wasn’t overpowering,” Gosger remembered. “I would say probably in the mid-80s.” But the pitcher managed to keep every pitch in the lower-half of the strike zone. “He was so consistent.”

Next came Dalton Jones, who hit a grounder to first base but ended up safe at second on an error by the A’s first baseman. Jones was immediately erased trying to reach second on a dropped ball by the A’s catcher, Bill Bryan who recovered in time to throw him out.

Then came the only Boston player who left an impression on Paige that night. “The young man’s name was ‘Yastrocki,’” Paige said. “He injured me.”

The young man’s name was actually Yastrzemski, but even the professionals occasionally struggled with that one. Coming into his best years at age 25, Boston’s left fielder was more than a match for Paige at 59. “I got in a hole with him,” Paige said. With a 3-0 count, Yaz “knew the next one had to be in there,” and it was. He laced a double off the fence in left center field.

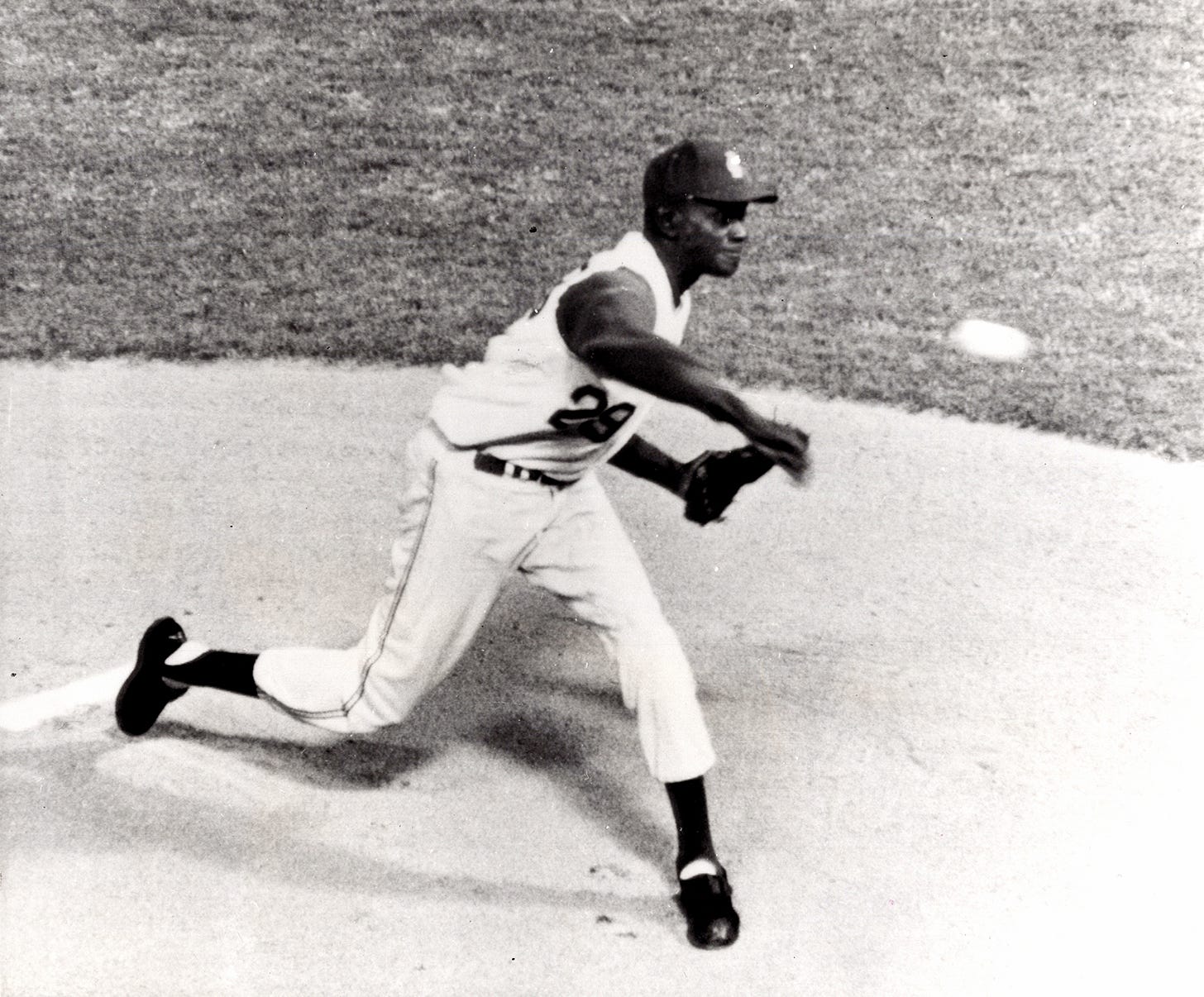

Paige got Tony Conigliaro to fly out to left field to end the inning. It had been a battle, particularly with the error prolonging things, but after 14 pitches, he was now fully loose. From there the Red Sox had no chance.

The A’s pitcher began carving up the Boston hitters with an array of fastballs, curve balls, and his famous hesitation pitch, which claimed three victims that evening, including Red Sox catcher Mike Ryan.

“It’s a hell of a pitch,” Ryan reported. “It comes up to the plate looking like a balloon. I laid into it but didn’t do anything with it.”

The befuddled Red Sox watched as Paige’s arms hung over his head, mid-delivery, using their own ingrained twitch reflexes against them.

“It was amazing to see,” another hitter said. “He would throw it hard or soft. Literally winds up, steps, stops, and throws—it was unlike hitting against anybody else.”

It took Paige just six pitches to retire all three batters in order in the second inning, and eight to finish the third. In between he took his turn at-bat and worked a full count before striking out. In the third he recorded a pointed strikeout, getting the Red Sox pitcher, Bill Monbouquette, with three straight fastballs. His old comrades from the Monarchs were watching the game from the stands and Paige could see them cracking up. “Cool Papa Bell loved it so much he pretty near had a heart attack,” Paige said. “He hadn’t seen me pitch in 15 years.”

Finley was determined to get Paige out on a high note. Surprise, novelty, and underestimation had carried the pitcher through the Red Sox’ order, but a second time through he’d be much more exposed and facing a lineup now eager to avoid humiliation.

Paige threw a few warm-up pitches to Bryan before manager Haywood Sullivan emerged from the dugout to take the ball. As the pitcher walked somberly off the field he swept his cap from his head and offered the cheering crowd a deep bow.

“I should have taken [Paige’s appearance] more seriously,” the A’s third baseman, Skip Lockwood, later reflected. “I was thinking it was part of the circus.”

By the number of animals on hand, it certainly might be a circus, but the man in the center ring was no clown. Getting professional hitters out had been his life for nearly four decades, including the last 12 years when most of professional baseball had relegated him into the archives. “He was a darned good pitcher even at that age,” Lockwood said, “and he took it seriously. All of us were witness to something historic, but I failed to realize it. I wish I had.”

Paige left the game with a 1-0 lead, but a succession of relievers could not reproduce his magic. The Red Sox took the lead in the eighth inning, capped by a two-run inside-the-park home run by the swift and spry Tony Conigliaro. The crowd’s mood was hardly dampened by the 5-2 loss—what was one more? Plus, the night’s real fun wasn’t over.

Satchel Paige was down in the A’s clubhouse. It had been a chilly evening (his nurse covered his spindly legs in a warm blanket) but now Paige was stripped down to a set of long underwear and reflecting on his historic outing.

He was quite pleased with his performance, all things considered. “Don’t forget I haven’t been up in this league in 15 years (it was actually 12, but point made). When I get back in shape there’ll be better things.”

A staffer rushed into the clubhouse to tell him he was needed back on the field. Paige found his way back into some clothes and made his way out into the park. The big stadium lights were out, but thousands of lighters and matches were glowing again, and the crowd sang for him. They sang “Rockin’ Chair,” “Darling I Am Growing Old,” and “The Old Gray Mare.” The track list showed Finley’s tendency to be too on-the-nose, but his Paige Appreciation Night turned out to be an evening at least as much for the honoree as it was for the owner’s bottom line.

After the festivities ended Paige shook Finley’s hand warmly. “I want to thank you for giving me a chance to pitch again,” he said. “ A lot of my friends here in my home town had never seen me when I was in the big leagues before.”

Finley called Paige “a real credit to the game,” and invited him to work in a public relations role for the A’s through the winter until spring training, when he could finish out his pension service time working as a coach.

Paige was concerned about his pension and about money generally, but he seemed curiously ambivalent about Finley’s offer. He noted that he was under contract with Abe Saperstein, founder and owner of the Harlem Globetrotters basketball troop. He’d hired Paige to work as an “advance man,” generating publicity and interest in towns ahead of the touring teams’ arrival.

He’d get no pension doing press for the Globetrotters, but Paige felt the tug of loyalty. “I was back in the woods for 15 years. It was Mr. Abe who brought me out into the light where people could see me. I’m twisted up pretty good with him. I don’t know whether the A’s could untwist me.”

The pitcher had long ago learned how to be congenial with the media, but he had never shied away from discussing the hard realities of his experience as a Black baseball star. The next day he was candid with a Baltimore reporter, saying that while he’d genuinely appreciated his opportunity in Kansas City, he didn’t see it as a favor. “Now folks can see that I must have had a lot more going for me,” he said, “and deserved to be in the big leagues when I was in my prime.”

It was no big deal for me to come back up here because I had no business being out. You can put it this way. You can say I resent being overlooked by organized baseball all those years while I threw away most of my best years pitching for a barnstorming club.

Everybody thinks it’s remarkable how I keep getting batters out in my 40th year of pitching. All they ask me though, is how old I am. But nobody asks me why I stayed out of the major leagues 15 years. That’s a long time isn’t it? That’s a lifetime for most professional players.

When Baltimore bought the St. Louis ball club, why did they turn me loose? When I went to the Miami club and was a top pitcher for three years, how come nobody picked me up? Somebody must know why.

Paige said he knew why. “But I won’t tell it, like I won’t tell my age.”

Later that winter the A’s granted Paige his unconditional release. The parting does not seem to have been on bad terms, but the pitcher was back on the road and still a few months short of qualifying for a pension.

In the summer of 1968, Satchel Paige made his last major league roster at the age of 62. “We hope we can use him as a pitcher,” said William Bartholomay, president of the Atlanta Braves, “but very frankly we want to make him eligible for a place in baseball’s pension.”

Paige was similarly cautious. He had been working for the Kansas City sheriff and doing fewer and fewer pitching exhibitions. “I don’t know if I can pitch now,” he said. “I’ll have to go out and try to unfold first.”

The Braves said they hoped he could work as a pitching instructor or, even more deservedly, “as a teacher of conditioning.” But this time the goal was simply to right one small part of a great wrong.

By February of 1969 Paige had still not quite finished his five years of service, but it didn’t matter, because the Major League Baseball Players Association, led by Marvin Miller, successfully negotiated the service minimum for a pension down to four years for all players. Paige’s pension vested, and the Braves took Paige to spring training anyway.

By the end of April he had evidently unfolded. Paige pitched a scoreless inning in each of the Braves’ final three preseason games against their Richmond AAA team.

“He can still pitch as hard as anybody for an inning,” a Braves staffer observed. “He showed he could. Since they were exhibition games, we didn’t allow bunting. He might have been in trouble if he had to field bunts.”

He was still throwing hard and still dissembling about his real age. “You know I’m more than 50 but you don’t know how much more. I know, but I’m not saying.”

The Braves weighed in on the question by issuing their conditioning instructor uniform number 65.

Close enough.

Two More Things

Project 3.18 always casts a wide net for story sources and “One Last Pitch” drew on more than 30 different period reports and articles. But we want to give special credit to this wonderful oral history by William Weinbaum, published online earlier this year. Weinbaum tracked down and interviewed Paige’s teammates on the A’s, the Red Sox, family members, and even located the rocker Paige sat in forty years ago. (Beat us to it.)

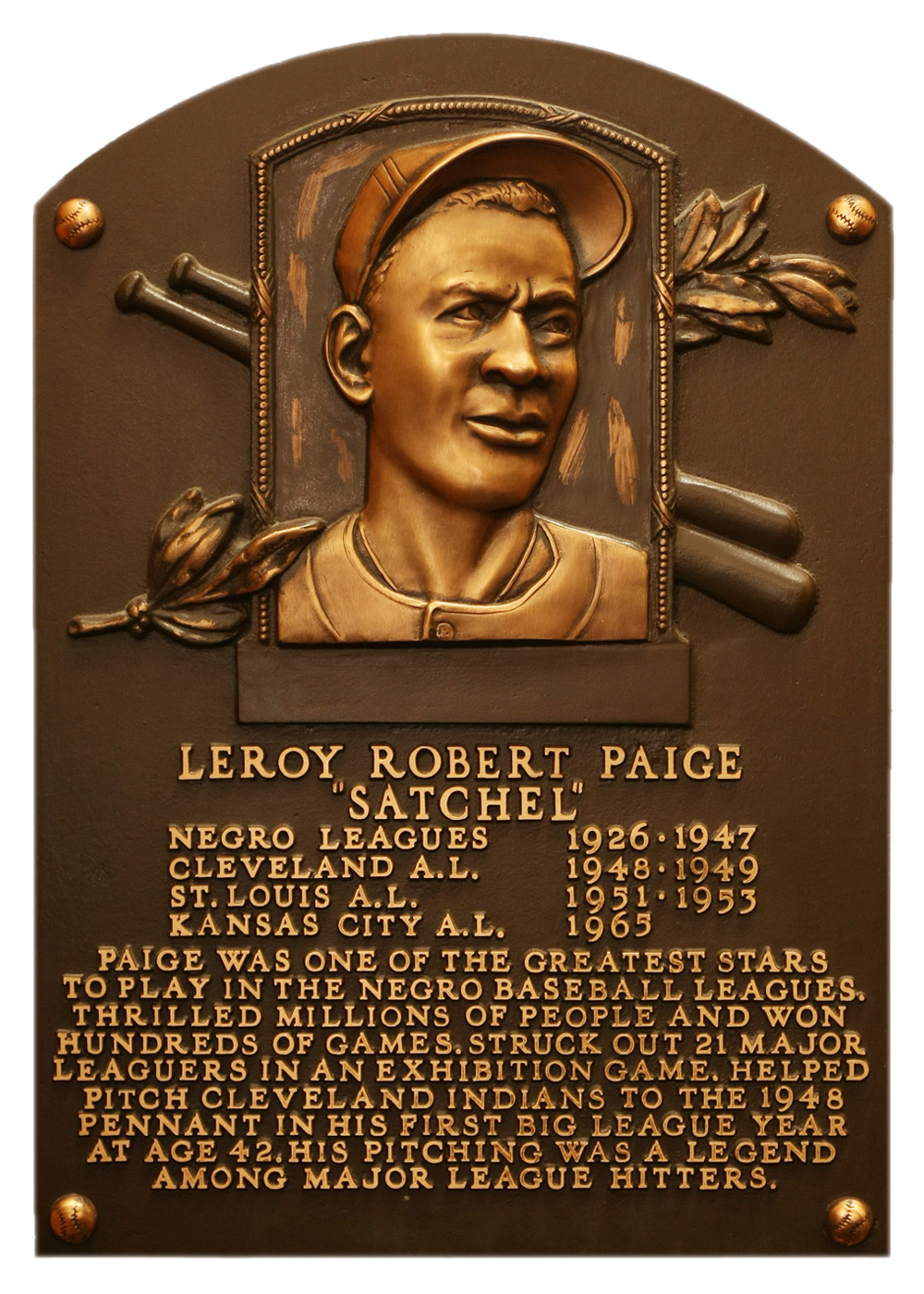

Video of Satchel Paige in action is sparse and available mostly in fragments, but we recommend this YouTube compilation of the best bits. This footage includes some from the night of September 25, 1965, which would one day become its very own line on Paige’s Hall of Fame plaque:

Great story about a great pitcher, one of the greatest living pitchers in September 1965. NB: Lefty Grove was also very much alive then.

Really loved the Weinbaum vignettes on Andscape.com. Hearing from Finley, Veeck, their sons, former players, family members was so interesting. That rocking chair and the nurse! I especially enjoyed watching Paige pitch in the YouTube collage. He did have his own style. I also found it so sweet that his 17 year old daughter was typing letters to different ball clubs soliciting a job for her dad. It netted him a September job of $4K in 1965. Not a bad stint; that would be about a little over $40K in today’s dollars. Well, I’ve gone on long enough. Another great post, Paul!