With the obvious exceptions of a slide into base or a diving catch, baseball is a stand-up sport. When a participant in a baseball game is on the ground for any length of time, something may have gone amiss, as was the case in the three instances we explore today.

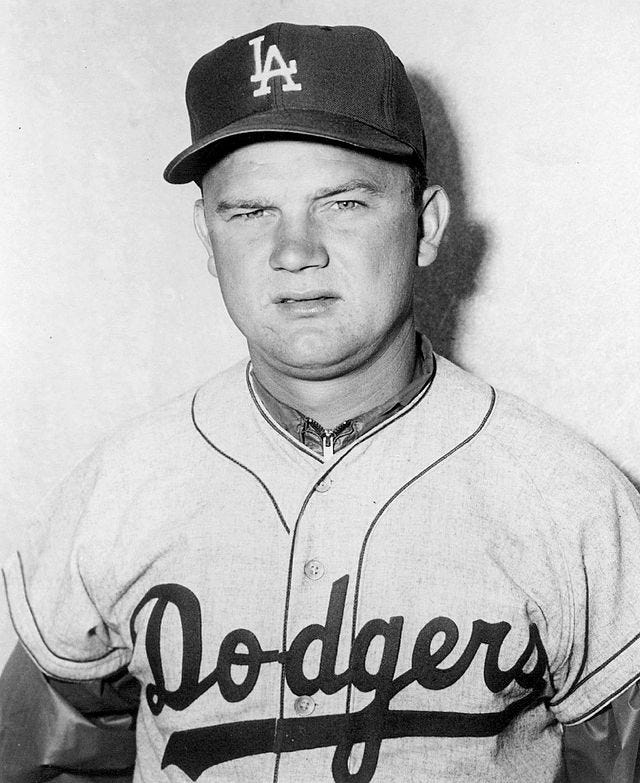

Don Zimmer, coach, 1985

Don Zimmer had a long, rambling life in baseball, as a player, a manager, and a coach. In between four managerial stints, Zimmer coached for eight different teams (the Red Sox and Yankees twice). As a player and manager, Zimmer’s ejection history is workmanlike, expected and proper. As a coach, however, Zimmer chased a little history, finishing with 13 ejections, the sixth-most for anyone serving in that role.

In 1985, Zimmer was working for the Chicago Cubs and coaching third base for manager Jim Frey. Zim was in his usual spot in the coaching box near the home dugout on April 17, 1985 while the Chicago Cubs played the Philadelphia Phillies.

In the bottom of the seventh inning, the Cubs were down 3-2 when the first baseman, Keith Moreland, banged a double with the bases loaded and one out, scoring all three baserunners. As the Phillies tried in vain to keep at least one run from scoring, Moreland tried to take third base. Awaiting him there were Mike Schmidt, the Phillies’ third baseman, and Joe West, the game’s third base umpire.

Moreland slid into the bag and West called him out—but the ensuing dispute had nothing to do with that call—even Moreland agreed he was out. Zimmer had no reason to object to the call, because he didn’t see any of that part. When the play ended, he was lying sprawled in dust of the baseline, wondering what had just happened.

Once he found his feet, Zimmer launched himself at Joe West, claiming West had tossed him to the ground.

This guy grabbed me by the back of the neck and fired me to the ground. What does he think I am? A sumo wrestler? I never had this happen before.

The other umpires quickly approached the irate Zimmer, who had to be restrained from attacking West, who calmly explained that the coach had obstructed his view of the emerging play at third base. West merely solved that potential problem. The crew chief, Doug Harvey, arrived to hear Zimmer out. “Harvey said he would have done the same thing if he had been umpiring at third. So I said, ‘Well, that makes you terrible, too.’” This may be a mild sanitation of the language actually used, for which Harvey ejected him.

“Doug Harvey doesn’t know what happened,” said Zimmer afterward. “He didn’t see what happened. I could have broke my back. I could have broke my neck. This is a big man. I’ve never heard of such a thing. I’ve been pushed and I’ve even been spiked but I have never been lifted off the ground like that.”

Joe West stood 6’ 1” and he was indeed a very big man. Don Zimmer was at this point 54 years old and probably a good bit shorter than his listed 5’ 9”. If what the coach alleged was true, this was a rather one-sided conflict in addition to a sneak attack. Zimmer fumed at being the one removed and disciplined, and threatened revenge.

He doesn’t have grounds to do anything. I’m the man with the grounds. What happens tomorrow if I walk in here with a darn neck brace on? Where would he be? My back’s starting to hurt right now even while we’re talking. My neck’s starting to stiffen up a little, too.

“I got nothing to say,” West said. “I didn’t do anything. Apparently he just got mad.” Well, the umpire did something, didn’t he? Zimmer didn’t horse-collar himself out there.

The incident led to a brief and we must say entirely-unresolved journalistic exploration of how and when umpires made contact with game participants in the course of fulfilling their sacred duties. Every umpire involved that day agreed that umpires regularly moved personnel one way or another to get them out of their line of sight.

“[West] must be in that position,” Harvey said. “Zimmer had to get out of the way. He collapsed to the ground. This kind of play happens to umpires all the time. We get it every third or fourth game.”

The day’s home plate umpire, Eric Gregg, said the same thing happened to him in the first inning of the same game. Gregg said the on-deck batter was motioning for Ryne Sandberg to slide home in the process of scoring the first Cub run, and inadvertently obstructed his view.

“I just shoved the guy aside. Same thing as West did in the seventh inning,” Gregg said. “You've got to do what you can do.”

So, what to make of this? Our ignorance of the technical work of umpiring is showing here, but if we stipulate that umpires routinely make contact with other parties while trying to do their job, perhaps this comes down to a case of West not knowing his own strength in how he handled the smaller Zimmer. Or not caring.

It is an interesting duo, Zimmer and West, and they would reunite for several more ejections across their baseball lifetimes. On three other occasions, West received discipline for making prohibited or excessive physical contact with players or other personnel. But on the other hand, this was not even the most well-publicized time that someone threw Don Zimmer to the ground. The guy was a terrier and every so often, he was under the wrong set of feet.

But do umpires really shove guys around like that? We don’t know what to make of it. Any umpires out there?

Frankie Frisch, manager, 1940

Yes, him again. On top of being a Hall-of-Fame-caliber baseball player, Frisch had a great sense of humor and a real knack for improvisational comedy, so we run across him a lot in this research.

On May 20, 1940, the Pittsburgh Pirates were in Philadelphia, facing the Phillies at Shibe Park. Going into the ninth inning, the Pirates had a commanding 7-1 lead. Perhaps that helped put Frisch in a jocular mood.

In the Pirates’ half of the inning, he was stationed in the first base coaching box when his center fielder, Bob Elliott, executed a surprise bunt. From Frisch’s perspective, Elliott beat the throw to first by two steps (a view shared by the writing corps). But Bick Campbell, the umpire involved in the play, called Elliott out. Reacting to the call, Frisch spread his hands above his head and fell backward to the ground in a mock-faint.

The theatrics were executed so well, Frisch might have prepared this material before coming out to the ballpark. “The small crowd of fans ready to leave Shibe Park were convulsed over Frisch’s perfectly-timed dive,” a local account reported. “The Pirates were up by six, so the players and the scribes in the press box, including the hapless Pittsburgh writers, had to grin over the Frisch back-flipper.”

The manager rose to his feet, but before he could take a bow, Campbell “gave him the thumb.” Frisch did not protest, something which the Pittsburgh Press suggested had never happened before. Comedy always comes at a cost, but this time, at least, he was glad to pay.

Every account agrees that Frankie Frisch exited the field after being tossed, but there is no consensus on how far he went. Some reports say Frisch made it all the way to the dugout and began to change his clothes, while others say the manager hid just inside the darkened tunnel between the clubhouse and the dugout and continued to surreptitiously manage. One certainly sounds more plausible than the other.

There didn’t seem to be much managing left to do. The Pirates failed to score and went into the bottom of the ninth with their six-run lead and their starter, Mace Brown, still in the game, looking to finish it.

The inning opened with an easily playable pop-fly into shallow right-center, but it dropped to the grass in a moment of misunderstanding between two veteran outfielders, Paul Waner and Vince DiMaggio1.

Brown went after the next batter and got him to pop up, too, and into someone’s mitt this time. After the out, Brown winced visibly and “his throwing arm seemed to droop.” In any modern context, a reaction like that would result in an automatic and immediate visit inside an MRI machine, but this was 1940 so instead there was an argument about whether Brown should keep pitching.

“When I came in at the end of the seventh my arm was a bit sore,” Brown said afterward (that a reporter did an interview is a bad sign):

I told nobody except Ray Berres [the Pirates’ catcher], for I knew I had the Phils’ number and figured I could go right on through. But at the end of the ninth, Ray came in and said, ‘Mace, you haven’t got a damn thing on the ball.’ I told him I knew it, but said I would ease a few up and get them out to end the game. Somebody must have told Frisch my arm was hurting me. Anyhow, Mike Kelly [one of the Pirates’ coaches2, running the game in Frisch’s absence], came out then and held up the game to ask how my arm was feeling.

Brown agreed, reluctantly, to come out of the game.

Frisch had [the bullpen ready] and I figured this way: What’s the use of me taking a chance of hurting my arm, so I will miss my next turn at the mound? Anybody can get the Phils out now, with a six-run lead.

“Oh, that ninth!” the Pittsburgh Press wrote. “It’s an unspeakable subject with the Pittsburgh players, but the writers would be remiss in their duties if they refused to report the nightmare.” Same, Pittsburgh Press, same.

The first relief man, the aptly-named Max Butcher, saw three hitters, allowing two singles and then a triple that drove them in. Meanwhile Frankie Frisch had the game on the radio in the clubhouse where he was dressing, and he now returned, partially-clothed, to the mouth of the dugout tunnel, demanding an update on Butcher and ordering him pulled. The next man in was Johnny Lanning, who allowed two singles before he got pulled, too.

Then came Dick Lanahan, who walked the first batter he saw, threw successive wild pitches, and then gave up a game-tying single. The bases remained loaded, with still just the one out, recorded by Mace Brown. Inside the tunnel entrance, Frisch now “lay in wait.”

Lanahan walked in the winning run. The Phillies had scored seven times. The Pittsburgh relievers yielded seven hits and four walks3.

As Max, Johnny, and Dick slunk out of the dugout, Frisch pounced, delivering what listeners described as “a clubhouse oration that has seldom been matched in any ballpark, any place, any time.”

Imagine a great fellow like Brown willing to pitch his heart out, a fellow who can save plenty of games for you other pitchers, and yet nobody can save one for him! What do you fellows want, a ten-run lead? You should all apologize to Mace Brown.

Mace was a recent conversion from the Pirates’ bullpen, having “saved an estimated4 40-50 games in expert relief duty” over the past six seasons.

It’s not clear how many sorries Mace Brown got from his relief corps, but it is not likely he accepted them. Afterward, he spoke with Pittsburgh writer Charles J. Doyle, who noted that Brown “referred to himself ‘Baseball’s Forgotten Man’ and used “a lot of hard language” during the interview.

I’ve saved about 50 ball games for this club and when I get in a little jam nobody can save one for me. Why, that first fly in the ninth could have been caught by a kid and we all know it. Listen, from here on out I’m going to relieve myself when I get in a jam from the mound. I’m just plain sick over this one–that thing out there is the worst thing that ever happened to me.

Doyle reminded Brown that he had been the pitcher of record for a rather famous loss, the “Homer in the Gloamin’” that helped the Chicago Cubs beat out the Pirates for the 1938 pennant in the season’s final days. It had been Mace Brown who gave up a two-out, two-strike, walk-off home run to the Cubs’ Gabby Hartnett, struck on the brink of the game being lost to darkness. Mace Brown walked off of the mound at Wrigley Field as Hartnett’s teammates and many a wild spectator joined him on his trip around the bases.

Surely that was Brown’s worst moment in baseball?

I’m telling you, this thing out there today is the worst thing I have ever seen since I’ve been in baseball and I don’t care if everybody on the club knows it.

Edd Roush, player, 1920

Note: 1920s sports writing is the peak of convoluted, old-timey baseball nomenclature. We’ll add a little glossary for the best bits at the end.

It’s back once again to that vortex of bad behavior, the Polo Grounds. Did the old stadium sit on a ley line? We tried to check this but ended up in one of those Google searches where you suddenly realize you’ve wandered into the proverbial wrong part of town, so we must leave it an open question (and update our antivirus software).

On June 8, 1920, the Cincinnati Reds were the visitors. The score was tied, 4-4, in the bottom of the eighth inning, when left fielder George Burns batted for the Giants. He hit a grounder up just up the left field line, which the home plate umpire, Barry McCormick, called fair.

The word wasn’t out of his mouth before [Reds catcher] Ivey Wingo5 tossed his glove into the air and followed with a high toss of mask. Up went the umpire’s right thumb and with the motion came instructions for Wingo to hie himself away from the battle.

Meanwhile, Burns advanced to second and then broke for third when the Reds’ left fielder, Pat Duncan, made what one paper characterized as a “mud heave” while throwing the ball in, missing the third baseman. The errant throw made it all the way to Wingo, who, despite having been ejected, gathered it up to keep Burns safely at third. Was that legal? Nobody seems to have clocked this at the time.

At any rate, McCormick ruled Burns safe at third on another close call. “From all sections of the field, the Reds moved plateward—as if to get into a group photograph.” All but one—center fielder Edd Roush.

With 8,000 fans looking on, the Reds’ star, far away from the dispute in the deepest recesses of the Polo Grounds’ yawning center field, decided to wait it out. He took off his glove and cap and lay down in the warm outfield grass, “gazing upward at the cloudy heavens.”

Meanwhile, at home plate, his teammates “smote the murky atmosphere with words, some of the more radical even going so far as to assert that Burns’ hit was foul by at least ten feet.” The argument lasted five minutes, then ten. “Umpires were pulling ingersolls from their pockets and threatening to forfeit a ball game.” After tossing his equipment “29 parasangs into the clouds,” the banished Wingo finally departed.

The drama took 15 minutes, but at last, “the Reds had used all the words they knew, several times over,” and the teams seemed ready to resume. McCormick surveyed the field. All seemed in order, until his eyes alighted on a prone figure in center, “stretched out at full length on the green sward.” It was Roush. Dude had fallen completely asleep, in the middle of a major league baseball game.

McCormick bellowed in his direction, but in the strange depths of the Polo Grounds’ outfield well, the noise didn’t travel, and Roush “continued his restful posture.” His teammates’ calls went similarly unheard. It was only when the Reds’ captain, Heinie Groh, made a trip out to shake Roush into wakefulness that he at last stirred. Having been fast asleep, Roush was slow to rise, and McCormick, his patience fully expended earlier, “put Roush out of the game for this exhibition of ‘lèse-majesté.’”

Then came another delay, during which the heretofore quiet Roush came roaring in, “to make inquiries of Mr. McCormick’s health and mental ability, and was restrained only by force from testing out the strength of the umpire’s jaw.“

There was more “watch pulling” by both McCormick and his umpiring partner, Pete Harrison. At length, Pat Moran, the Reds’ manager, was able to move Roush as far as the dugout.

Once play resumed, it did not take long for the Reds’ worst fears to be realized. Gifted two close calls by McCormick, Burns scored the winning run from third via the very next batter (and another error by Pat Duncan out in left, who was getting muddier by the minute).

Speaking of ingersolls, even with several lengthy delays, this was breakneck baseball by our standards—the game still finished in just two hours!

1920s Glossary of Rhetorical Antiquities:

“Hie”: to go quickly

“Ingersoll”: a brand of watch, used here as Kleenex often stands in for facial tissue today

“Parasang” (Persian): any of various Persian units of distance; especially: an ancient unit of about four miles. Would readers of 1920 sports sections really have gotten this reference?

“Lèse-majesté” (French): to give offense against a monarch/leader

Like many other Monday Substackers, we’ll be coming to you on Tuesday next week, after the Memorial Day holiday. We’ll start what will surely be an ongoing study of seat cushions, but as is so often the case with Project 3.18, there’s a twist:

No old-timey translation will be necessary, because this story is from 1987!

However, you may want to brush up on the food chain in small-scale, freshwater ecosystems, because that’s going to come up.

On May 28: “The Days of Whine and Cork”

The Kevin Jonas of his time and vocation.

Know who else was a coach on that 1940 Pirates team? A 66-year-old Honus Wagner. Imagine being a rookie arriving at Pirates camp for the first time: ”Here’s our hitting coach, you may be familiar with him.”

When we researched this piece a week ago, no modern comparison leaped to mind. And then…four pitchers, six runs, six bases-loaded walks! Well, at least Paul Skenes was good.

The language here rings a bit odd, but in 1940 there was no official statistic for a save, though there obviously was a commonly-accepted definition that allowed for some unofficial recordkeeping.

Ivey’s brother, Al, also played major league ball. That’s quite a contrast, we thought, naming one kid “Ivey” and the other one “Al,” so we checked: Al Wingo was born Absalom Holbrook Wingo, and yeah, that’s better.

Another fun entry! It got me to thinking… 1. Either yesterday or the day before I caught just a bit of a game while sitting in a bar. The runner did a flying somersault over the catcher to make it home safe. Pretty impressive move. How often are there such acrobatics in baseball? Do they practice that stuff? 2. What impact has technology had on baseball, whether it be umpire calls or game reviews or training? Just wondering …

Throwing a player out of a game for sleeping - that is truly a unique story.