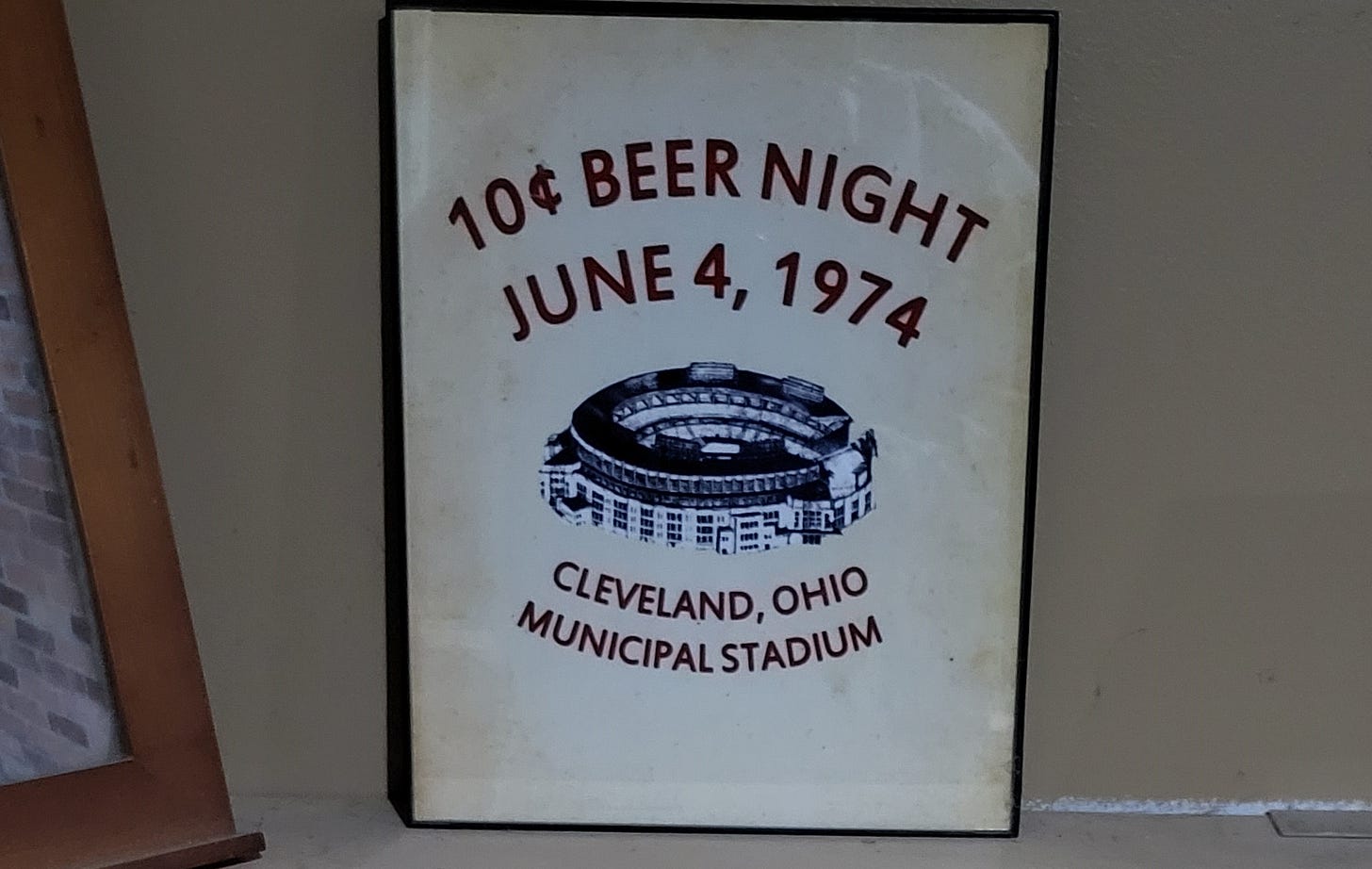

(Re)Remembering Ten Cent Beer Night

In Cleveland, it's often said of June 4, 1974: “If you can remember it, you weren’t there.” Not true for these guys.

This is Project 3.18, a newsletter where we remember moments when baseball didn’t go as planned, tell stories with the fans, and write about history and culture through the lens of the National Game.

If you enjoy this article, you can use the provided button to subscribe and receive future stories for free in your inbox; and please help share it on social media, via email, or a more vintage method of your preference.

And don’t miss the archives, full of forfeits, ejections, and wild tales from every era of baseball.

For years, an Ohio relative offered to make an intriguing connection: Some of her high school buddies had attended Ten Cent Beer Night, and not only that, a few of them had been a part of the…on-stage party, if you will.

The first time she mentioned it, I was doing other things, but a dozen mentions later, my life had changed and I had resolved to tell this story again, from the perspective of the fan(s). So, she put me in touch with the old crew, who enthusiastically shared their stories from Ten Cent Beer Night.

When it happened, it wasn’t anyone’s proudest moment, but 50 years later, Project 3.18 is proud to bring you out onto the field during the wildest riot in modern baseball history.

MEET THE GUYS

RICH: Whenever somebody brought up Ten Cent Beer Night, I’m always the guy saying, ‘Well, I was there!’ And they say, ‘oh, sure you were. You just read some article, now you're going to tell us about it, aren't you?’

Rich mentioned that he had read, among numerous others, the original article I wrote about Ten Cent Beer Night. (And if you know nothing about the nuts and bolts of what happened at TCBN and want to learn, may I humbly recommend my 2008 work to you, before you go on with this 2024 remaster.)

DON: 280,000 people say they were there, but there were really only 25,000 of us, whatever the real number is.

25,134, including four high school pals from a town about an hour outside Cleveland: Don, Rich, Wayne, and Reggie.

We spoke with Don and Rich over Zoom, and were joined by one member of the old gang, Marty, who wasn’t at the game, but should have been (we’ll get to that story).

RICH: I caddied at a country club as a teenager. So I had money, I had a car. And, so it just ended up that I drove. It was a blue Rambler, so we called it the Midnight Rambler. I was a big Mick Jagger fan.

Rich was one year older than Marty and Don, which meant that, at 18 in 1974, if anyone checked ID’s, he could buy the alcohol, even though he did not really drink. This did not end up being a problem at Ten Cent Beer Night. Being of legal age and willing to drive made Rich the archetypal “stand-up guy” in the group.

DON: Rich always drove. I called him our Getaway Driver.

That’s true—it’s how he introduced Rich to me over email. Don spent a lot of our conversation making space for his friends to tell the story, until the moment when he knew he would inevitably take center stage. He struck me as an appreciative friend with an evidently gentle demeanor. If, based on deportment alone, you asked me which of these guys was going to end up down on the field during Ten Cent Beer Night, Don would have been my last guess.

MARTY: As usual, it was my idea to go to the game, for the cheap beer promotion. I read about that in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, which I read every day.

Marty clearly took pride in having been what I’d call the group Activator. Every friend group needs one. He did the planning, figured out what everyone was going to do, and got everybody marching in one direction. 50 years later, he’d landed, perhaps inevitably, in politics.

DON: From my memory, there was no inclination that anybody was going to that game to challenge the Texas Rangers, or for revenge. I just think it was, ‘hey, a promotion,’ and like Marty was saying, it sounded like a fun time.

MARTY: We thought, hey, if you want an opportunity to get a cheap drunk when you're 17-18 years old, this is it, right?

DON: That's what gets me, we're 17 years old. I mean, we were going for a beer promotion. I keep doing the math and thinking: ‘No, I couldn't have only been 17?’ Yeah. We were 17!

MARTY: It was definitely about the beer, but we all knew about the Arlington brawl and so that built the anticipation. That's what I loved about baseball back then, man: You came in spikes-high on somebody, you're getting one in your ear hole the next time up, right?

In other words, after what had happened in Texas, the people of Cleveland were about to put one in the Rangers’ ear.

EARLY INNINGS

RICH: We were sitting on the right field, first base side, somewhere around there.

DON: Like if you drew a straight line, we were halfway down right field.

I could go down and get a container that held six soft drinks, and I got six beers in there. I really don't remember being that intoxicated. It was the kind of beer that you just drink as much as you want. You're just gonna pee it all out.

MARTY: Yeah, it was 3.2% beer wasn't it?

RICH: I think they were 12 ounce cups.

DON: The cups were plastic, the kind that if you squeeze it, it broke. I don't remember how I got beer. Rich, were you getting us beers or were we just walking down to get beer?

RICH: I don't remember having to show an ID or anything like that. I was probably drinking the least. I just remember everyone else drinking beer. And I remember the whole place smelling like beer.

DON: There was trash and beer everywhere; I mean, your ankles were wet because of beer all over the place, basically.

The night was like a stage production. A girl came out and kissed one of the umpires, or tried to. And the guy streaking, who ran to second base in the early innings. When that guy slid into second, everybody in the park laughed.

Then he ran to the center field wall, and the cops were chasing him—the stadium cops. And he’d go one way and they’d go after him and he’d go another way, almost like a Keystone Cops movie, you know,1 and then finally he flipped over the wall and escaped, and everybody went crazy. More cheering for that than anything in the game!

RICH: And then there was that woman who came out of the stands. I remember she looked like the housemother from The Facts of Life.

RICH: Seeing somebody just go out and take her top off, I mean this was craziness, to us. That was the point when everything broke loose.

Up until then, it was a baseball game. If you knew about the Arlington brawl, maybe you're rooting hard for the Indians or whatever. But this lady comes out, and that opened the gates. There was another lady that tried to come out, and I think they escorted her out, maybe an inning or two after that.

From there on, it was just pure craziness. And when you see someone, a guy, nude, run out and slide into second base…

MARTY: Another poor decision!

RICH: As an 18 year old, I'm standing there going, ‘what is going on here?’ And then the next thing we've got, what looked to me like a father and son duo going up the center field pole, the one with the American flag.

MARTY: I'm listening to the whole thing unfold on the radio and I hear, ‘Guys are streaking, guys are climbing up the flagpole with no clothes on!’ What idiot would climb up a flagpole with no clothes on? I mean, that's gonna leave a mark.

RICH: And soon we’re seeing 25 people go from left field to right field every half inning—nude. This is not something you see, even in 1974! It started out as individuals, but by the seventh or maybe even the sixth it was crowds, coming out in hordes and everyone's nude.

LEEEERON / JENKINS

Quoting…well…myself:

“Interest in the game itself peaked in the fourth inning, when Indians batter Leron Lee swatted a line drive back to Rangers pitcher Fergie Jenkins. Jenkins could not get out of the way and caught the ball with his stomach. As he writhed in pain, the fans began to clap. A chant began:

‘Hit him again, harder!’”

RICH: I don’t think the beer promotion caused the crowd to celebrate when Jenkins got hit. That wasn’t a reaction like, ‘ha ha, we're all drunk.’ It was: ‘I hope that hurt.’ That reaction really started the hostility.

And the other thing, and I don't know whether it's ever really been documented, but what caught my eye in this whole thing was the stuff people were doing to Billy Martin and the Rangers.

Behind the dugout, guys were tying strings on their firecrackers and throwing them over the dugout, so they would swing back in. That's what got Billy Martin really angry. This is the stuff that brought him out with a baseball bat. And he was holding a bat, I'm gonna say, maybe from the fifth inning on. The fact that nobody got hit with that bat was really surprising to me.

DON: Yeah, that really upped the hostility, the Billy Martin stuff. That’s when it started to turn from a fun and crazy hippie-fest. It became, like, ‘oh, that asshole, look what he’s doing now.’ The beer started to amplify everybody's moods in a negative way and every time they'd see his face, they’d get madder.

RICH: I was shocked with the ingenuity of the guys throwing firecrackers on strings. And to be honest with you, a little bit afraid of it too. I was thinking, ‘come on, now, that's jail time.’

MARTY: From my perspective, 60 miles, 70 miles away, the announcers were just disgusted. I mean, Joe Tait was just disgusted: ‘There's another idiot. Yeah, there's another idiot, there's idiots everywhere.’

DON: Martin was coming out of the dugout to make, maybe, a pitching change or to talk to the pitcher and somebody threw a wine bottle at him.

All of this was putting fuel in this thing. By the sixth and seventh inning, it was just a free-for-all and it was like, nobody had any regard. There was nobody trying to stop anybody on the field. It was mostly between innings, so people would clear off and the game would go on, until that magical ninth inning.

THAT MAGICAL NINTH INNING

MARTY: I know the Indians tied the game. It was 5-3. And they tied it at 5.

DON: Yeah, they brought in three bench guys. One was a catcher, I think [Alan Ashby]. And they got like three hits in a row.

Facing Texas reliever Steve Foucalt with one out:

George Hendrick doubled to left

Ed Crosby singled to center (Hendrick scores)

Rusty Torres singled to center

Alan Ashby singled to third base

John Lowenstein hit a sacrifice fly into center (Crosby scores)

DON: By then, there was no order. It was just…it was Woodstock.2 It was out of the realm of baseball.

MARTY: And let's not let's not forget also that It was 1974. So if you think beer was the only thing that was being consumed at that time… There were probably Quaaludes involved. There was probably plenty of pot being smoked. I mean, that place [Municipal Stadium] was a free-for-all normally, let alone throwing the ten cent beer in there.

DON: The baseball was a side note. The crowd became the show.

We came to the point in the evening when Jeff Burroughs, the Rangers’ right fielder, had a run-in with a fan.

MARTY: Jeff Burroughs. That's a name that these guys can expound on a little bit.

DON: So, that's what got me. That's what got me onto the field.

ONTO THE FIELD

DON: The game was tied up and several people were still running back and forth across the field. I vividly remember a young fan who did the wrong thing: He was running by Jeff Burroughs as Texas was making a pitching change, and the kid grabbed his hat. And Burroughs had the wherewithal to turn around and grab this kid by the back of the shirt, and what I saw was Burroughs drop the kid, and then his foot went down in a kicking motion. If that happened or not, I don't know for sure.

But to me, it looked like he kicked the kid. And then I was running, on my way down the aisle stairs towards the field wall. And other people were doing the same thing. It seemed like hundreds of people were rushing the field because of that kid. I have to assume they were all caught in that moment because they saw what I saw.

Don said that once he reached the field, the young fan who’d been tussling with Jeff Burroughs had already escaped, leaving Don and the others—their mission scrubbed—to scatter into guerrilla activity.

DON: I ran, and I think I went by a cop who was chasing after me. As I was running, I looked over my shoulder and the Indians and the Rangers are all out coming out of the bullpens, trying to protect themselves because this had turned into an instant melee.

And I remember a chair came flying right over my head and it hit [Cleveland reliever] Tom Hilgendorf. It hit him right in the head. I was right there. I was about 10 feet away from that, because that chair went right over me. It was a wooden folding chair. It could have been a ball girl chair, or a bullpen chair.

I backed away and Hilgendorf went down, and people cleared back and there was a relief pitcher, one of the Rangers, I don't know who it was, but he was standing there with a cocked baseball bat and he says, ‘Take one more fucking step closer. Take one more fucking step closer…’ and that's when I said to myself, ‘whoa, whoa, I don't know if I should be here.’ But I continued my run because there was another scuffle going on down by the pitcher’s mound. It seemed like it was probably three or four minutes that I was down there, because by the time I got down to the pitcher's mound, it was just all people, like a rock concert.

RICH: Yeah, this was totally chaos. This was—you'd have to really think about whether you wanted to get on that field, if you weren't like my Killer Don here.

Don said when he ran back toward the infield he saw our future manager, Mike Hargrove [a rookie playing first base for Texas], who we didn't know at the time. Hargrove was pounding the heck out of somebody on first base.

DON: As I ran down that way, I ran right into the face of [Cleveland center fielder] George Hendrick. He had these eyes that pierced me like a laser. That's when I felt like I was about three feet tall and I said, ‘I shouldn't be here.’

Then a security guard bear-hugged me from the back and ran me over towards the first base dugout area and through a gate. I ran back up to find my friends, who didn’t know I’d gone onto the field. They were like, ‘where the hell were you?’

RICH: I remember saying, ‘what the hell were you doing?’

DON: Well, I didn't know what I was doing. I should not have been there in the first place. I realize all that. It was just probably the adrenaline.

MARTY: When they ended up just canceling the game, I heard the radio announcers say that one of the players was chasing a guy in the outfield. Honest to God, I thought to myself, ‘that's got to be one of my idiot buddies.’ I mean, I would have bet a thousand dollars. I had one of them that came right to mind.3 But I would say, Don and Rich would be the two least-likely guys.

I wouldn't think that either one of you guys would go down there and want to throw down with a professional ball player.

RICH: Hey, come on, now. I've thrown down with some guys. I got sucker-punched on many occasions!

ETHICS IN BASEBALL RIOTS: A PRIMER

This next part of the conversation surprised me.

‘Why was I out there?’

With his story, it would have been all too easy for this older, wiser Don to laugh off his infamous trespass as a product of his still-developing frontal lobe. Kids, amirite?

But that wasn’t how Don processed the question. Rather, it seemed to turn him quickly and reflexively inward: Why was I out there…?

In fact, he’d asked this of himself at some length over the years, suggesting the answer was of personal importance. How many people who were out on that field examined their actions like this, near-term or long-term?

DON: I can't find a reason to blame it on alcohol. It seemed to me that I saw something wrong, you know? I think what I had focused on was the fact that the kid was young and a player was taking advantage of him. I'm the kind of guy who, if I see something wrong, I tend to react.

After the kid escaped, then it was just curiosity.

MARTY: I'm gonna say this about Don: I know him to be a ‘see wrong, take the right side’ kind of guy. So I can believe that that's exactly where his head was at.

RICH: Here's where the difference comes in, as far as I'm concerned. I was of the feeling that the kid kind of deserved it. Burroughs was looking toward home plate, this kid just runs up behind him and knocks his hat off.

There never was like, a square-off, you know, Burroughs was ambushed. He must have thought, ‘wait a second. I don't know who else is behind me,’ because there were people running from left field to right field the whole night.

MARTY: As you look back now, it's understandable that Burroughs would react like that. He doesn't know if it's 15 people or 30 people. But at the time, all you could think was, ‘That's wrong. He's the bad guy. Let's go get him.’

RICH: I can't begin to tell you how scary the whole situation was at that point, or could have been. Because these people had baseball bats and yeah, they didn't want to hurt anybody, but they could have…

DON: I think that there have been articles on the person who actually took Burroughs’ hat, and he said, of course he was wrong in hindsight, years going by, but I think he was 15 years old at the time.

RICH: Yeah, he wasn't very old, but you can see why the Rangers came out on the field.

DON: Oh, they were protecting their lives. Yeah, they would protect their lives.

RICH: Because all they see are people coming out of the stands. And they're like, ‘we gotta go.’

MARTY: I seem to recall Tait and Score saying that they felt like Burroughs was in danger.

RICH: He was in danger. He was.

MARTY: He didn't know 17-year-old Killer Don was on the loose!

DON: Sorry, it's tough to lose a reputation when you got one.

MARTY: Don’s nickname back then, by the way, was ‘Donut.’ Not exactly a killer nickname.

RICH: And mine was ‘Moosey.’

MARTY: Donut and Moosey. Couple of killers right there.

DON: We left on our own accord. I don't recall being forced out. I recall an announcement that the game was forfeited. And people, as they left, after the altercations, I think everybody realized that they had just been a part of something bad. I think it was like, ‘what did we just do?’

RICH: I’ve seen pictures of Hilgendorf. From the stands, the fans, we could tell that that happened. Once we found Don, we left pretty quickly. We didn't want anyone coming after us, you know…

Discount beer promotions were far from unusual in 1974, and they had mainly gone off smoothly, until this one…didn’t. This one produced—as Don had put it, with real feeling—“something bad,” drawing in a lot of people who (with the exception of the guys swinging firecrackers) hadn’t necessarily set out to be bad. So…

WHY THIS ONE? WHY DID IT GO BAD?

Nobody had the answer—I’m not sure there is one—but it’s interesting to see everyone’s math on the question, which is why I ask.

MARTY

MARTY: Who hit the ball that hit Jenkins? Leron Lee, yeah. The fans were chanting like, ‘hit him again,’ or something. Get him again and hit him again, like the old football high school football cheer, right? See, to me, listening to it, I heard the disgust from Joe Tait at that moment.

I think that right there just helped escalate the poor sportsmanship of the fans. It helped create greater tension.

DON: Yeah, it magnified everything.

RICH

RICH: Where have you ever been that you've seen a hundred people nude? Even in this day and age. Well, the lady who came out and just baring her chest, without any real consequence. I think that opened the door to a lot of drunk people to say, ‘let's go.’

DON: There was not much security involvement. I mean, it was really minute, the security.

MARTY: That was one of the biggest mistakes.

DON: So, I think everybody just thought they had liberty to do whatever they wanted to. You know, you leave the kids without a babysitter, what happens?

DON

DON: I'm telling you, I believe everybody was in the same mode as I was. That kid was in trouble. [Helping him,] I think that was the intention, because everybody in the group I was involved with was traveling in his direction. Emotion took over, believe it or not.

Obviously it's not one of my proud moments in life. I can't lie about that.

RICH: I was proud of you, Don.

MARTY: We were all proud of you, Don.4

DON: That's pretty much it. Every once in a while I get asked, so I repeat the story and then I wonder if I still tell it the way it really happened. Rich, you had gotten a hold of me and said HBO was doing a 25th anniversary, or some kind of anniversary.

Somebody got a hold of me from HBO and asked me to tell the story over the phone. Then we're looking, they were looking for a ticket stub or something, anything that I could show, but I didn't have anything. So anyhow, she says, ‘what happened?’ And I say, ‘well, jeez, I could tell you what I think happened.’

MARTY: So it's 50 years later now. And Don, to me, the story you told when I saw you the next day, is the same story that you just told. I think you've been pretty consistent.

Hey, let me tell the story of how I got screwed out of being at Ten Cent Beer Night.

THE OTHER TEN CENT BEER NIGHT

Hearing Don’s account, it’s easy to see why the night’s events left such a vivid impression, no matter how much “3.2” beer he had, even becoming an impetus for interrogating his own youthful character. But if he didn’t get to go, why did Marty even have a story, let alone one he was so eager to tell? What’s to remember?

MARTY: We bought the tickets. At the time, a couple of us, me, Rich, Reggie, we were working at a gas station. Well, the day before Ten Cent Beer Night, I go to our manager: ‘Hey, by the way, I need tomorrow night off because…’ And he goes, ‘Oh, Reggie already took the night off. You can't off.’ And Rich was already off.

So Reggie took my ticket and went to the game that I made all the plans to go to. Reggie, God, I should have killed him like 18 different times.5

So, on Ten Cent Beer Night, I am steaming. Another side note here is, in the summer of 1974, If you research it, you'll find that was when we had a so-called Gas Shortage6

So, cars would line up and down the street for the gas station, and back then we very rarely took a credit card. It was all cash. We just stuffed cash in our pockets. And then the manager would come out and relieve you of your cash. Just keep pumping and stuffing. So I'm listening to the game on a radio. And it's getting stupid crazy and I'm laughing and it's a warm summer night.

And I'm telling people that are pulling in, ‘Hey, are you listening to the Indians game, you gotta turn on the Indians game.’ I'm going down the line telling people to turn it on. So now everybody's got their windows open. Traffic's backed up for two blocks, everybody's got their windows open and you could hear the game. You could be standing a hundred feet away and you could hear it because everybody had it on. It was really cool. You know, today that would never happen.

It delighted me to discover this alternate version of Ten Cent Beer Night living as vibrantly in Marty’s memory as the real thing did in Don’s. Yes, there was the howling, sparking chaos of the field at Cleveland Municipal Stadium—certainly that was Ten Cent Beer Night. But there was this quieter, lovelier inverse. A less epic scene, certainly, but just as evocative: a warm Tuesday evening in June, a high school senior stuck working outside, serving a bunch of similarly-stuck commuters, none of whom had a phone, let alone a pocket entertainment system, waiting in line for punishingly-expensive gas. All they had were each other and their car radios.

With a little encouragement from the friendly neighborhood gas pumper, this dispiriting fuel queue bloomed into spontaneous community. Headlights pierced the humid darkness and illuminated summer insect swarms while idling American-made engines kept up a rumbling purr two blocks long. Over all that noise, you still could hear, from everywhere, the sounds of a baseball game (or whichever version of Woodstock had supplanted it in that moment).

Where Marty was, 60 miles away from the action, that was Ten Cent Beer Night: a line of cars, their windows rolled down and their radios on, the sounds of Joe Tait and Herb Score’s dismayed narration crackling through the air as people’s imaginations brought the described scene to shared life. For Marty, Ten Cent Beer Night was neighbors and strangers talking, shaking their heads in disbelief, forgetting their glum circumstances and laughing about the game.

No wonder he had to share that story.

I do not, but I left a link.

The first two-thirds of the game leaned toward Woodstock ‘69, while this latter third presaged the vibe of Woodstock ‘99. It’s a cross-generational reference!

Marty would have put it all $1,000 on Wayne. Sorry, Wayne. Or, maybe, congratulations? Only you and Marty know.

All three of these guys were the dude-iest of dudes. Let it never be said that dudes don’t express feelings. It just has to happen in the course of talking about baseball.

Marty then recounted several of the 18 times he should have killed Reggie. These anecdotes were compelling, but cut for relevance.

From Wikipedia: “The average US retail price of a gallon of regular gasoline rose 43% from 38.5¢ in May 1973 to 55.1¢ in June 1974. … Politicians called for a national gasoline rationing program. President Nixon asked gasoline retailers not to sell on Saturday nights or Sundays; 90% of gas station owners complied, which produced long lines of motorists wanting to fill up their cars while they still could.”

Happy 50th anniversary! The story that started it all! Love this perspective on it.

Great stuff.

My son and I just got back from a baseball road trip, Cleveland on Saturday afternoon and Pittsburgh on Sunday. (As an aside, this Paul Skenes looks like he just might amount to something.) We got to Progressive early, and while strolling through the concourse saw a long line of Guardians fans queued up for I knew not what. Turns out you could buy $2 pints of Miller Lite until first pitch. My Econ major boy tells me that a dime in 1974 would get you about 65 cents worth of 2024 beer, so the deal was not as good, and it didn’t last long. It still made me laugh that out of the 25 parks we’ve visited over the years, we didn’t find cut-rate beer at a baseball game until we reached Cleveland.