Saying Goodbye to the A's

The story of the last time a city lost the Athletics franchise.

Baseball’s treatment of the city of Oakland and the now-couch-surfing franchise that had a home there has been a continuing travesty. Of course the team’s ownership is most responsible and gets that credit, but the other owners and the commissioner have powers and influence here; all of which they have failed to use, and here we are. It’s a bad day for baseball.

Yesterday a version of this piece ran in Here’s the Pitch, the newsletter for the Internet Baseball Writers Association of America (IBWAA). Because this is Project 3.18 (word-limit free since forever), this version of the story comes with an expanded (and happier) conclusion.

May we one day be able to write a similar ending for Oakland.

Given MLB’s prudent decision to schedule the end of the A’s season on the road in Seattle, the Athletics franchise will play their final home game for the city of Oakland today. As the Bay Area says goodbye, let’s look back 57 years (less one day), to September 27, 1967, the last last night of A’s baseball.

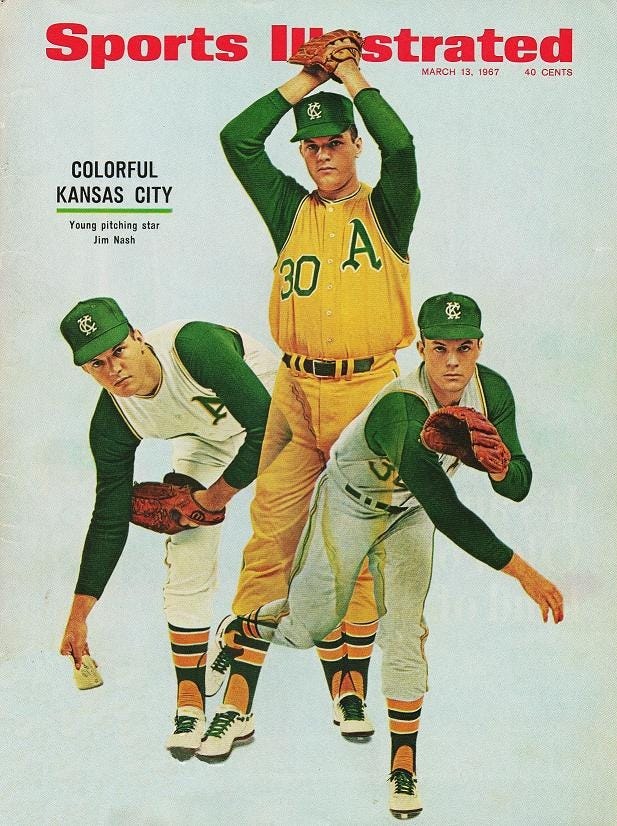

By 1967, there was no doubt that the A’s owner, Charles O. Finley, planned to move the Athletics out of Kansas City. It may be that the Chicago-based insurance executive always had designs on taking the A’s elsewhere, having unsuccessfully bid for the team first in Philadelphia, but after successfully purchasing the team in 1961, he made some (literally) symbolic gestures towards staying, like putting the name of the home city on the jersey for the first time in franchise history. But Finley quickly became unsatisfied with the team’s drawing power in Kansas City (and the city name was banished from the jersey after just one year).

Finley had unsuccessfully sought permission to relocate at least once before 1967, but the other owners weren’t ready to accept the Kansas City situation as hopeless, nor were they prepared to sanction a relatively “quick-hook” of an established team. So the owner kept publicly and privately complaining until 1967, when he tried again, and at that point the worn-down American League was ready to appease his obsession with finding a greener pasture somewhere beyond the fence-lines.

Finley’s plans and the owners' impending acquiescence was broadly known by September 27, 1967, when the Kansas City A’s played their final home date of the season, a double-header against the Chicago White Sox.

It was unseasonably cold for Kansas City in late September, with temperatures in the low 50s and frost warnings punctuating the forecast. Fans came to Municipal Stadium bundled up and carrying extra blankets. Inside the park, hot chocolate and coffee outsold beer at the concession stands.

For one team, there was meaningful baseball. The visiting White Sox were in a photo-finish race with Boston and Detroit for the pennant, and winning both games of this double-header against Kansas City would give them the lead with three games to play.

The home crowd of 5,235 people knew what they were getting into, both in terms of the chill and the impending departure of the team, heading west at the command of owner Charles O. Finley.

“Might as well see the A’s now,” one of the fans said. “We might not see them again.” Others nearby agreed, remarking that these A’s would certainly be moving to Seattle for 1968.

Conversations were easy to overhear that night. Elsewhere in the quiet park, the thwock of pitches into the catchers’ gloves reverberated in the upper levels, where isolated packs of kids hunted foul balls.

The A’s took a commanding lead by the end of the sixth inning. Reporting for the Kansas City Star, Charles T. Powers wrote that the crowd “sounded like 10,000” when the A’s chased the Sox’ starter, Gary Peters. The A’s won, 5-2, and about half of the satisfied crowd headed for the exits. It was too cold.

Powers felt that many of the remaining fans seemed dazed. They stood quietly around the concession stands, topping off their coffee, their faces “as blank and cheerless as a bus load of rush-hour commuters,” giving odds on where their team would go next.

In between games, a young woman named Letha Luster was unironically introduced as “Miss Transportation,” as chosen by the Kansas City Transportation Association. Finding herself in a bit of an awkward situation, Miss Luster said, “I just hope we can transport enthusiasm about the A’s here in Kansas City.”

The second game featured an excellent pitching performance by the A’s Catfish Hunter, who pitched his twelfth complete game and his fifth shutout. Just one White Sox player reached second base. These A’s seemed like strangers already, playing spoiler to an erstwhile pennant-winner, rising up from the bottom of the American League standings to deliver two lethal blows.

Even the misbehavior felt subdued. The crowd of freeloaders who snuck in over the press gate after the second game started and the ticket offices were shut could be counted on one hand. The only on-field trespasser was a loose dog, easily captured after Catfish Hunter tricked it into a gentle but restraining embrace.

With Hunter clearly not about to let the Sox into the game, more and more people left with each run the A’s scored, taking one long look back at the field and making an instinctive shrug as they turned and disappeared into the concourse tunnels.

Kansas City won 4-0. The victorious A’s left their dugout quickly and without ceremony, filing out a back door down the long passage to their clubhouse. Next to their coverage, the Star ran a photo of that quiet line of departing men, with pitcher Diego Segui at the rear, the last Athletic out of Kansas City.

After the players left, kids gathered around the dugout steps and pestered the bat boy for a souvenir. “Come on buddy,” one said. “Give me a bat. You don’t need it. You’re going to Seattle.”

In the clubhouse, players dressed, signed autographs, and practiced being diplomatic. Like Miss Transportation, this wasn’t really even their fight.

“We may never play another game in Kansas City,” Hunter said, “and the whole team wanted to go out a winner. And we did it.” Speaking of the uncertain future, the A’s best player in 1967 was half-apologetic, half-pragmatic. “I’d like to stay,” he said, “but I’ll have to go wherever the team moves. We’ll have to do our best wherever we play.”

At other lockers nearby sat future All-Stars, millionaires, and Hall-of-Famers–the bones of a dynasty that would break the sport competitively and then transform it financially. Hunter and Blue Moon Odom; Sal Bando, Joe Rudi, Bert Campaneris, and rookie Reggie Jackson (who was absent that night, having received permission to leave early and resume his college studies). One day, many of these players would be able to go where they pleased, but in 1967 they were along for the ride.

The A’s last act in Kansas City was to crush the White Sox’ pennant aspirations. Hoping to leave in first place, Chicago limped away in fourth. Powers, the Star writer (and future novelist), wondered if the pennant stakes had been a draw, yielding one of the better crowds of September despite the larger circumstances. But that wasn’t it, he decided.

“The strongest magnet was the human compulsion to witness the death, to sit in on the wake, or simply say good-bye. For it had been widely rumored, generally feared, occasionally hoped and, last night, finally accepted that the Kansas City A’s were playing their last game as the Kansas City A’s.”

Today, we know this story has a happy ending for Kansas City. But unlike events in Oakland today, Kansas City said goodbye with good reason to believe that their baseball future was secure. The next day, September 28, two pieces of correspondence made national sports news.

In a letter to the city manager, Finley confirmed he did not intend to exercise his option to rent the city’s Municipal Stadium for the 1968 year.

“I have decided,” the owner anticlimactically wrote, “to take the steps necessary to transfer the Athletics to another city.”

This letter was forwarded to the mayor, Ilus Davis, who released it to the public. “One thing is fairly certain,” the Associated Press reported all over the country, “the A’s won’t be in Kansas City next year.”

Also that day, Mayor Davis received a letter from the secretary of the American League, inviting him to attend an upcoming owners meeting on October 10, “to discuss an application…to transfer the Kansas City A’s franchise to another location effective for the 1968 season.”

Near its conclusion, the letter also noted that U.S. senator Stuart Symington (D, MO) had also been invited to attend the meeting. This was the tell. The league wouldn’t dare call Stuart Symington to a meeting like this unless there was good news to share about the future of baseball in Kansas City.

Symington had made a national reputation when he helped discredit and dismantle fellow senator Joseph McCarthy’s Communist inquisition, and he had made a baseball reputation by threatening to burn the sport to the ground if his constituents lost their access to major league baseball to Finley’s wandering eye. If the league didn’t take action to fix things for Kansas City—and quickly—Symington vowed to introduce legislation that would lead to the revocation of baseball’s prized antitrust exemption and support lawsuits challenging the reserve clause which so effectively constrained the economic rights of the players. No one thought Symington was bluffing. The result was a little game of franchise musical chairs.

Even as Finley finalized his plans to depart, “sources inside the league” reported that Kansas City would receive one of two forthcoming expansion teams to replace the A’s.

“Kansas City will not be left barren by Finley’s departure,” the United Press wrote. “Expansion could come as early as 1969 and certainly no later than 1970.” Stuart Symington would make certain it was the former.

After a half-decade of dealing with the volatile Finley, many in Kansas City saw the silver lining in the situation: a fresh start. As a result, their advocacy was for keeping baseball and not so much the A’s.

“Kansas City has both the desire and the right to uninterrupted major league baseball,” Robert Ingram, the president of the Chamber of Commerce said in response to the news. “I firmly believe that through the years Kansas Citians have proved that they appreciate the game,” including their recent approval of a $43 million dollar bond for a new sports complex. Ingram finished his statement by putting the spotlight back where it belonged:

The question now is whether the American League is genuinely major-league. Their action in maintaining baseball in Kansas City will indicate not only to Kansas Citians, but to the entire nation, whether baseball is major-league or bush.

So often in our work, we are reminded the aphorism (attributed to Mark Twain) that history does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes. 57 years later, the mess is left in Oakland, and Ingram’s question is once again the right one to ask.

This is Project 3.18, a newsletter where we remember moments when baseball didn’t go as planned, tell stories with fans, and write about history and culture through the lens of the National Game.

If you enjoy this article, you can use the provided button to subscribe and receive future stories for free in your inbox. And don’t miss the archives, full of forfeits, ejections, and wild tales from every era of baseball.

I was ten when the A's moved to Oakland. In my mind they will forever be the Oakland A's. I can't see Las Vegas as a baseball town. We'll see, personally I think everybody will be sorry.

Thanks for another great report.

I loved this story so much. I know there has been an avalanche of negativity surrounding the As leaving (again), and justifiably so. But am I the only one excited for a Las Vegas baseball team? I realize it’s very sad for Oakland, but Northern California still has a fine baseball club, and now Nevada gets a baseball team.