The A's of Aquarius

Facing the loss of his stars, Oakland’s owner hired a stellar expert to guide the team to one last title.

The Oakland A’s entered 1976 riding high, having won five straight division titles—not to mention three world championships—but events early that offseason cast shadows on the team’s future. In December 1975, a third-party arbitrator upended baseball’s labor landscape, essentially nullifying the “reserve clause” in the contract that had kept players’ fates in the club owners’ hands for nearly a century.

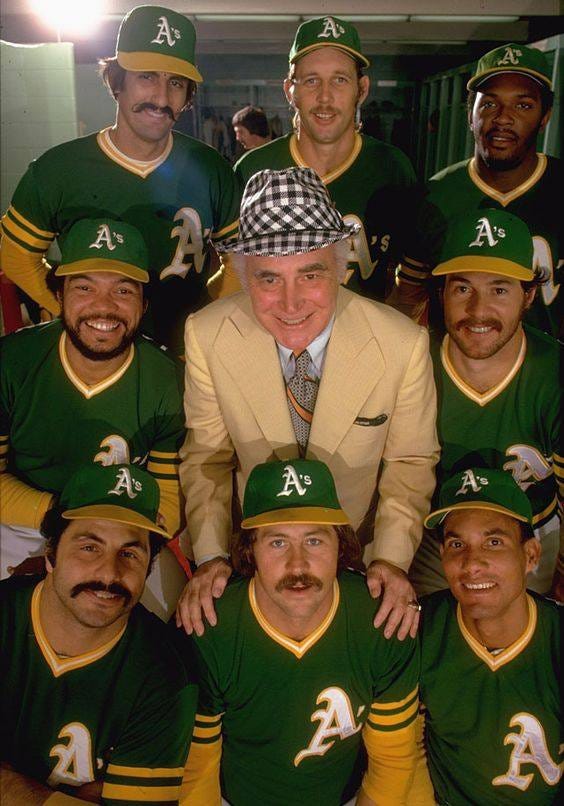

No one welcomed the demise of the reserve clause more than the core members of the Swingin’ A’s. The team’s on-field success belied the constant acrimony between the players and the owner, Charles O. Finley. Though a visionary executive and a shrewd judge of talent, Finley was also an absentee owner who cut his players’ wages after a down season, reneged on binding agreements, and often made his world champs fly commercial. Now, thanks to the arbitration decision, so long as they did not sign a new contract, after 1976 the captive A’s players would be free to go.

The onset of free agency was an obvious threat to Finley’s masterpiece. By number of unsigned players or level of talent, no other team was so exposed:

Reggie Jackson - right field Joe Rudi - left field Bert Campaneris - shortstop Gene Tenace - catcher Sal Bando - third base Vida Blue - starter Ken Holtzman - starter Rollie Fingers - reliever

Unless Finley would open his wallet and set baseball’s first free-agent market by offering big-money contracts, the team of the decade was one summer away from oblivion.

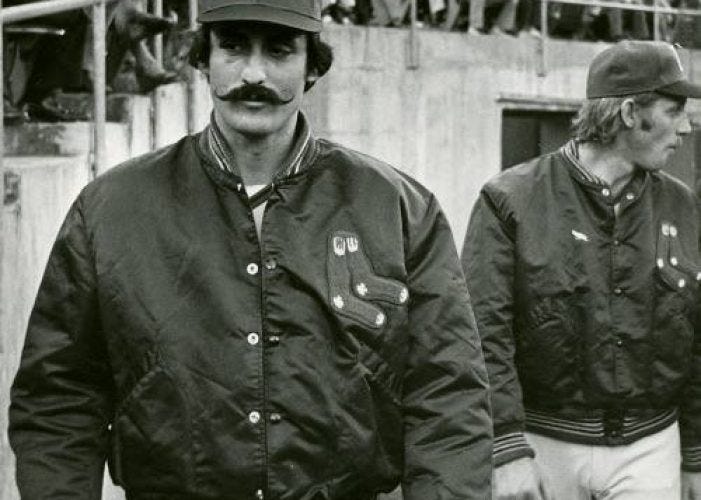

The A’s had a new manager in 1976 and Finley had gotten him at a discount. Chuck Tanner was well-regarded, but his White Sox had taken a turn for the worse in 1975 and the team was under new ownership. Tanner was let go with three years left on his contract. Believing the White Sox were still on the hook to pay him, Finley made Tanner a lowball offer he couldn’t refuse.

Meanwhile, the unsigned A’s players rebuffed Finley’s chintzy contract offers; many broke off negotiations altogether after he leaked their “exorbitant” salary expectations to the press. The owner traded Reggie Jackson and Ken Holtzman to Baltimore at the beginning of April for players Finley hoped would be easier to sign.

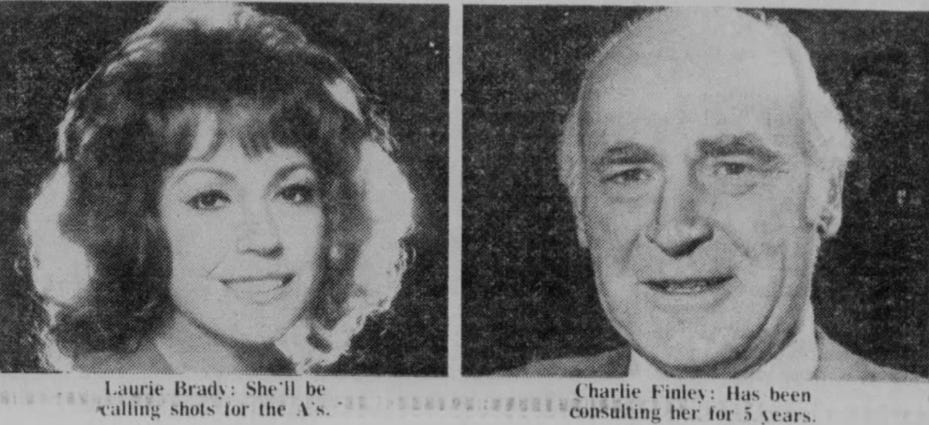

On April 13, Finley at last announced he had someone under contract, but it wasn’t Campaneris or Tenace or Bando who joined him for the press conference. Instead, the A’s owner introduced a Chicago astrologer, a woman named Laurie Brady.

Laurie Brady was, first and foremost, a Cancer (early summer), along with Scorpio (mid-autumn) and Pisces (late winter). These facts may tell any astrologers reading this all they need to know, but we’ll add a few more details for the laypeople.

A native of Ottawa, Illinois, Brady spent several years studying to become a nun, but ended up a beauty contestant, leading to a few small parts on television, including acting as a “prize money assistant” on a short-lived bowling show in 1960. She may also have worked as a belly dancer somewhere in there, and she definitely married a lawyer and moved to Chicago in the late 1960s.

Around the time of her marriage Brady made a very shrewd investment in a 1920s-themed Chicago “gentlemen’s club,” the Gaslight, which grew successful enough to expand to other cities in the United States and Europe. As a part-owner of a flourishing business, Brady was independently wealthy before the age of 40, and when her marriage ended, she was free to live whatever life she wanted.

Brady initially came to astrology as a skeptic. She took a magazine assignment to attend a convention and try to debunk the pseudoscientific practice. “I wanted to disprove certain things,” she said. “I couldn’t see how you could cast the future.”

The convention, we must mention, was a “swingers” convention, a very niche interest area indeed. Brady seems to have expected to find little astrological similarity among the attendees, but she discovered the opposite: hundreds of swingers overwhelmingly shared related astrological aspects. The project led her to reconsider astrology and then some.

By the early 1970s, Brady was an established name in a New Age business. Working out of a posh condo in a luxury apartment building overlooking Lake Shore Drive on Chicago’s North Side, she regularly appeared on radio and television and wrote regular astrology columns for tabloid publications like the Sun and the National Enquirer.

Brady’s baseball connection moved into her building in 1970. The Chicago-based Charles O. Finley needed a place to crash when he didn’t feel like returning to his Indiana estate, and he and Brady became part-time neighbors. The two shared biographies during a series of piecemeal elevator exchanges, and when Finley learned what she did, he asked Brady if the A’s were going to win the World Series that year.

She told him it wasn’t happening—hardly a brazen claim as Oakland never even touched first place—but the astrologer surprised Finley by predicting a run of success that even he hadn’t dreamed of. Starting in 1971, Brady saw the A’s winning five consecutive division titles. When the ascendant A’s won the AL West in 1971, Finley flew Brady to Oakland to watch the playoffs against Baltimore.

Four AL West titles (and three World Series championships) later, Finley finally asked Brady to do his astrological chart. It predicted health problems, and the 58-year-old owner soon ended up in a hospital with a significant back issue. The doctors warned of a long inpatient recovery, but Brady told him he’d recover within a few days. She was right again, and before he even left the hospital, Finley offered Brady a job in baseball.

“It is the first time, definitely the first time,” Brady said at her introductory press conference. “I am very up on what people are doing publicly, astrology-wise.”

As a woman entering the hypermasculine world of sports journalism in the 1970s, Brady’s physical credentials initially received as much attention as her professional ones, not the least from Finley, who described her as both “nationally renowned” and “a vivacious redhead, an Irish girl with the most beautiful black eyes you’ve ever seen.”

Brady had probably made peace with this type of commentary. She was cagey about her age and her work clothes seemed to be gold halter-tops, leather pants, and jewelry that made the A’s World Series rings look like they’d been fished out of a cereal box. Every sportswriter calling her “stunningly attractive” and reciting her figure measurements like a player’s batting line was free advertising for her glamorous brand, and unlike any baseball player, she got to be her own boss.

“I don’t do seances,” she said. “I have business hours. I’m a businesswoman first and an astrologer second and I have been self-employed for 17 years.”

In an interview with the Star, home to Brady’s regular astrology column, Finley insisted Brady’s hiring was not a gimmick. “Baseball is serious business with me. I will seriously consult her as I have in the past. She is amazing, simply amazing. Her predictions have never been wrong.”

The mechanics of astrology chartings were such that Brady would work remotely. She could do a full work-up using just a person’s date, time, and place of birth. Those details were plugged into the enormously complex body of astrological lore and the result would be an individualized personal road-map. As Brady explained:

Astrology kind of goes along with biorhythms of the bodies. I made a chart for each of the players, when their energy levels are high, what days they will play better than others, and when they are more susceptible to having accidents and making errors. In this way the manager will better know whom to use and when.

Finley said Brady would have “appointments” with the players when the team visited Chicago in May, presumably to go over their charts. But in the meantime Brady would mail week-by-week digests to Chuck Tanner.

The A’s manager kept a low profile as the news of Brady’s hiring swept across the sporting world, but Brady predicted the new hires were going to get along just fine:

Mr. Finley told Chuck about me and Chuck promised to give me his complete cooperation. I don’t foresee any problems. All of us are water signs. Mr. Finley is a Pisces and Chuck Tanner and I are Cancers–we’re both Moon Children.

Finley was delighted with Brady’s top-line prediction for 1976, in which the A’s were a “cinch” to earn a sixth-straight division title. Addressing skeptical reporters, Brady could have equivocated, but she didn’t.

“It looks like the A’s are going all the way again.”

While Chuck Tanner was never likely to act on the basis of Brady’s mailed-in advice, early in the season there were a few instances when he appeared to at least be paying attention.

Paul Mitchell was a starting pitcher who came to Oakland in the deal for Reggie Jackson and Ken Holtzman. The right-hander had spent most of the spring in the minors after a rough debut, but he was recalled in May and inserted into the rotation. On May 10 he gave a strong performance against the California Angels, striking out 10 in six innings. After the A’s 6-3 victory, Tanner went out of his way to acknowledge that Brady seemed called this one.

“Look at this,” he said, pulling out an “Astrological Form Chart” for Mitchell, which Brady had mailed the week before. “It says right here Mitchell will be good on May 10 and 11, so I can’t say I was surprised.”

In late May the A’s made their first trip to Chicago to face the White Sox. Before the first game of the series, Finley (who rarely left Chicago) threw a staff dinner at a trendy restaurant. As the guests dined on lobsters and steak, Chuck Tanner and Laurie Brady made nice in front of the invited media.

“I believe in this astrology business up to a certain point,” Tanner said. “There must be something to it. She sent me a letter saying that Paul Lindblad, the relief pitcher, was due to reach a peak on a certain date. I didn’t pay much attention to the letter, but I had to use Lindblad on that particular day. He went 6 ⅔ innings and saved the decision for us.”

This was typical phrasing. Tanner was willing to say he looked at Brady’s material, but never conceded he’d used it to make a baseball decision.

Charlie Finley sat between his two big offseason acquisitions during dinner, but otherwise seemed more interested in showing off Charlie O, the team’s mule mascot, who had won the owner’s love in a way that none of his human employees ever managed.

“I was one of the first people to ride the mule,” Brady offhandedly told a reporter. This was almost certainly not true, but who could fact-check that—and who would bother?

Finley had souvenir T-shirts made for the female dinner guests, each emblazoned with Brady’s name, or, rather, what he thought was Brady’s name. The shirts’ iron-on letters spelled “L-A-U-R-A.”

“See?” Brady said. “The man is too busy to even learn my real name. But he is a dynamo.”

With Finley doting on the mule and Tanner excusing himself to Comiskey Park as soon as decorum allowed, Brady got to tell her own story, and, as ever, she did not water down her beliefs for a mainstream audience.

When one skeptical columnist asked her about her divorce and whether she’d seen that coming, Brady seemed almost to troll him, replying that not only had she seen divorce coming, she knew why the marriage failed: “The stars showed [my ex-husband] was my son in a former life.”

When talk turned to baseball, the team astrologer got serious, making predictions as bold as they were granular. She told reporters the A’s were “certain” to win that night. They lost, 6-0. She’d also said that Vida Blue was going to have a bad game, and he did. So why predict a “certain” win on a night when the team ace would struggle?

The A’s arrived in Chicago having lost five in a row, and when they left, the losing streak had reached eight. Brady, of course, had a diagnosis. “Too many of the players were born around the same time of the year and have the same horoscope. It just means that when one is down, a lot of them are down.”

By early June, the A’s, once an astrological “cinch” to win the division, were stuck below .500. In a short blurb published in Time magazine, Brady now predicted first-place Kansas City would win the division.

Finley appeared to tolerate some bad news, as long as it proved true. ”She predicted we wouldn’t do well against Chicago last weekend, and they kicked the living dickens out of us.”

But Brady told Time she had learned what every other Finley employee already knew. “Mr. Finley is rather difficult to work with. When I tell him negative things, he gets angry.”

By late June, Finley and the A’s were bogged down in the biggest crisis in baseball that season. The owner had failed to sign his outgoing players to new contracts, and in a fit of desperate pique he now put them all up for sale. Midseason trades were a baseball staple, but as the negotiations went on, it became clear that Finley was looking for only cold, hard cash in return.

He claimed the plan was to use the money to restock the A’s with young, controllable talent, but couldn’t explain how exactly that would work. Skeptics saw an attempt to offload costly contracts and line his pockets before a possible sale of the team. But what appalled many of Finley’s fellow owners were the asking prices. The Boston Red Sox had agreed to purchase Rollie Fingers and Joe Rudi for $1 million apiece, and the Yankees would take Vida Blue for $1.5 million. Just before these and other comparable players hit the open market, the Finley deals were setting that market in seven figures.

The horrified owners sent in their unlikely sheriff, the commissioner, Bowie Kuhn, whom Finley instinctively loathed. Citing concerns over “competitive balance” and “the integrity of the game”—anything but money—Kuhn announced he was pausing the transactions while he consulted with the clubs involved. Rudi and Fingers had already reported to their new team, who happened to be in Oakland to play the A’s. After saying goodbye to their teammates and being photographed in Red Sox uniforms, Kuhn ordered Fingers and Rudi back from whence they came.

Kuhn pretended to think things over and then nullified all three deals. Finley sued the commissioner and refused to play Rudi, Fingers, or Blue, declaring he would not risk injuries to someone else’s property. It was a circus, one the team astrologer claimed she’d seen coming long before the tent went up:

I warned Finley last October that by the end of June things would be very chaotic for him and his team, and that he would have legal problems that would drag on for some time.

You didn’t need to be an astrologer to see how the prospect of free agency threatened a financially-vulnerable owner who ran a home-grown, cost-controlled juggernaut, but Brady put her own spin on the obvious dilemma.

Mr. Finley is so psyched in with his team’s chart that it has a highly disorganizing effect. The team is so closely aligned with him, that its future is his future. In addition, he has terrible aspects of Mercury right now, so he won’t be thinking on an even keel.

But Finley hadn’t heeded her warnings. “Mr. Finley got very upset when I told him not to trade his players,” Brady said in 1977. “I also told him Bowie Kuhn would win the lawsuit.” She got that right, and it was probably then that Finley decided not to renew her contract.

The A’s owner had wanted a lucky charm, and Brady was extremely charming and—since their first fateful meeting in the elevator— had been extremely lucky. And despite her commitment to the nuances of astrology, she’d been willing to give Finley what he wanted, offering him any number of “thumbs-up” pronouncements on his team. Votes of confidence made him happy. Hearing that his aspects of Mercury were terrible did not.

Brady had little else to say as the drama played out. The remaining A’s threatened to strike unless Finley put Rudi, Fingers, and Blue back in uniform, and with minutes to go he backed down. The AL West was not decided until the final week of the season, when the A’s and Royals played a pivotal series at the Oakland Coliseum. The A’s needed to win all three games and won two. They finished just 2.5 games behind1 Kansas City. Oakland’s streak of division wins ended, as did Laurie Brady’s remarkable run of top-line predictions.

When the courts ultimately sided with the commissioner, Finley lost five of his best players—including Rudi and Fingers—for nothing. After a messy fight over who was supposed to pay Chuck Tanner’s salary, Finley traded his full price manager to Pittsburgh.

The owner introduced Jack McKeon, the next manager on the A’s now-gutted carousel, in January 1977. He also announced that Laurie Brady would not be back: “Jack will not have the benefit of a star gazer.”

Charlie Finley’s catastrophic June and July probably ended his interest in astrology, but in the context of the 1970s, there was some merit to the initial experiment. New Age methods were popping up in old industries, including sports, where some athletes kept hypnotists on call and others practiced transcendental meditation. In the never-ending race to find and exploit new advantages, perhaps a team astrologer might prove as helpful as a team psychologist. Laurie Brady would tell you the two weren’t that different:

A lot of people don’t understand the real purpose of astrology. We’re not trying to outwit the cosmos. We’re trying to use it for personal growth.

Her year as the A’s team astrologer was Laurie Brady’s big crossover moment, but Brady remained a mainstay in her industry, writing syndicated columns, doing media appearances, and consulting for VIP clients like Ed McMahon, Peggy Lee, Ernest Borgnine, and Robert Goulet.2

She commanded prime rates for individual sessions, and between those and her business investments, Brady was comfortable enough to have a little fun with her chosen profession, as evidenced by the “Pizza Horoscope” she put together in honor of National Pizza Week in 1987. An excerpt:

Cancer: Moody, compulsive eaters. Like stuffed pizza. When emotionally upset, prefer cheese and sausage; when happy, shrimp pizza.

Leo: Great eaters, pizzas with anchovies, ripe olives, Canadian bacon. When in love, preference is for ham.

While Charlie Finley eventually moved out of the building, Brady lived and worked out of that same apartment overlooking Lake Shore Drive and Lake Michigan for the rest of her life. She was remarkably consistent, down to her preference to be photographed in front of the same Zodiac sculpture on her wall as decades passed and astrology’s mainstream moment came—and went.

When she died in 2016 at age 86, Brady’s year in baseball was well-marked in an admiring Chicago Sun-Times obituary. Though it hadn’t necessarily worked out, the attempt said a lot about her:

“She was a savvy entrepreneur at a time when society often cast women in the roles of mothers and homemakers or members of what used to be called the secretarial pool.”

In the stars or in herself, Laurie Brady saw differently. She and Charlie Finley had that in common. They were both water signs, after all.

Did you know we launched a podcast last week? Clear the Field features great baseball stories and two co-hosts who love telling them. Give us a listen!

During the two weeks in July when Finley capriciously kept Rudi, Fingers, and Blue (who missed two starts) on Team Limbo, the understaffed A’s went just 6-5. Terrible aspects of Mercury indeed.

For our younger readers: these are the names of celebrities.

Astrology and baseball, what a combo. I never knew this existed. Certainly part of the culture back in the 70s. I remember the National Enquirer and halter tops and another astrologer named Jean Dixon (who wrote for the NE). Let it be said that Laurie most likely wore hot pants! I hope this story makes it on Clear the Field. Thanks, Paul.

I actually don’t remember too much about her but this definitely gives me an idea. Retirement is boring so I’m gonna order me another’Magic 8 Ball’ as I have no idea where mine was as a 10 year old & I’m gonna call Brian Cashman of the Yankees. After all he gave his daughter two shoes on the YES network so maybe you’ll be seeing me on TV soon Paul.

PS - My Oujja Board must be around somewhere too.