The Break-Up

The real story of the most famous piece of chain-link in the National League is a story of lost love--and the rise of the ballpark surveillance state

Researching our previous installment, we were perplexed to see Pete Rose declare in 1988 that the Wrigley Field “goat run” was put up because of Cubs fans’ angry, projectile reactions to his presence in their outfield. At first, we didn’t even know what he meant1, but we think we figured out the reference: Rose was talking about the four-foot, slanted fence that juts up and out from the entire outfield wall on the North Side’s biggest jewel box. “The basket” has been robbing outfielders and ruining no-hitters since 1970, but in our recollection, Rose had nothing directly to do with it. Could we have been wrong?

If Pete Rose had inspired or necessitated the basket, first we had to figure out what (specifically) he had done to warrant such hostility that the Cubs felt it necessary to dramatically alter their ballpark in an effort to protect him. Two events emerged as contenders.

On July 1, 1967, Rose, running through first base, accidentally spiked the top of Ernie Banks’ foot, forcing the first baseman to leave the game. Rose “endured boos” for the rest of the day while Banks got 12 stitches. Any potential beef was quickly quashed by Mr. Cub, who said he’d mistakenly left his foot in the middle of the base. Rose called him a “great guy” for whom he had a great deal of respect. Nope, not it.

Our second lead was a doubleheader on August 18, 1968, something about Rose complaining about a Cubs pitcher “doctoring” a pitch, so we looked into that, and…

…found a story so bananas we’re dropping everything to bring it to you in the very near future. But the one thing that incredible game did NOT have was a connection to the installation of the outfield basket.

Having checked our work again, we feel that the story of Wrigley’s outfield fence is not one Rose can claim for his c.v.

Rather, it is this story: the sundering of a remarkable relationship between the Chicago Cubs and their own fans, and one group of fans specifically: the Left Field Bleacher Bums.

The Bleacher Bums—a confederation of students, night-shifters, retirees, and the purposefully unemployed—took up residence in the left field bleacher seats at Wrigley Field mid-way through the 1960s and became famous/notorious in 1969 as the Cubs seemed destined for a pennant, or at least a division title. The Bums—known for their yellow hard hats, semi-religious devotion, and a repertoire of customized songs and cheers–were characters that every magazine and newspaper in the country could use to tell the story of Cub Power as it swept Chicago and vaulted the team back into contention after decades in the wilderness.

A New York Times profile, written in late August 1969, right as the Cubs’ roller coaster reached the top of the final, steepest hill and began to descend, was typical in the pointed credit it gave Cubs fans–and a subset of them, specifically:

When and if the Cubs clinch the pennant, the credit must go to a hustling young team, manager Leo Durocher, and the regular patrons of the left-field bleachers–not necessarily in that order.

This was the North Side’s trinity, and the hard-hatted holy ghosts of Wrigley stood on the outfield wall with megaphones and bugles, directing cheers and chants from their 200 organized members and thousands of gadflies and hangers-on, with the help of a few of the Cubs’ players themselves.

For a group devoted to leisure, Bleacher Bums were ambitious and organized, run by a full C-suite (located in a dive-bar across the street) of appointed officers. A charismatic and itinerant bartender served as president and face of the organization, by virtue of his longevity, commitment, and ability to “shout the loudest.” An associate at a real public relations firm did rather incredible part-time work as the Bums’ PR director and media liaison. A retired Chicago vice cop served as “legal advisor.”

As the frontrunning Cubs took the spotlight in 1969, these ramshackle administrators soon had the national media and the Cubs organization taking care of them as one takes care of a beloved but irascible pet. That August, Philip K. Wrigley, the owner of the Cubs, paid for about 50 hardcore Bums to travel to Atlanta and attend a key series against the Braves, where they dutifully proceeded to wreak havoc and make absurd headlines. The aforementioned president rented a bear costume and hunted the Braves’ own mascot right out onto the field.

The Bleacher Bums became a kind of good-luck charm and font of inspiration for the Cubs’ players, who would give anyone credit if it meant a playoff spot.

“They get everyone going,” the Cubs’ team captain, Ron Santo, said at the time. Once, late in the season, the third baseman walked out to left field on a bad knee to inform the left field fans he wouldn’t be starting that day because of said bad knee and that he was sorry. Years later, in his memoir, Santo’s belief in a Special Relationship was just as fervent: “I truly believe, to this day, that the crowds were a catalyst for our success from Opening Day on.”

First baseman Ernie Banks, the celebrated Mr. Cub himself, of course was aboard this train: “A ball club sometimes performs better than it really is just because of that extra encouragement up there in the stands.”

“There was a great relationship between the players and the fans,” shortstop Don Kessinger remembered. “Like nothing I had experienced before.”

It went beyond the field, too. The players often made sure that traveling Bums had tickets when they made the long interstate drives to follow the club. Perennial ace Fergie Jenkins even let a few Bums crash on the couch of his St. Louis hotel room on at least one occasion. “They’d stay, then leave about 3:30 AM, and I had no idea where they went. The next morning, I’d see them again, and they’d come in for room service.” Some of the Bums visited catcher Randy Hundley in the hospital as he recovered from knee surgery.

Even Leo Durocher, the aged and notorious curmudgeon who managed the Cubs, embraced the Bums. “These are some kind of fans,” he told Sports Illustrated in a 1969 Cubs/Bums summer profile.

They’re absolutely frantic with joy and happiness. They are in seventh heaven and you can’t blame them. Their screaming and antics are marvelous and just bring the club on. They have exuberance in their hearts. And this is the attitude of the players. They smell the roses, they smell the money. They have an attitude of desire and determination. They feel they can go out and beat anybody.

In return for his blessing, the bleachers made Durocher a senior citizen-celebrity, roaring whenever he emerged from the dugout, mellowed by age but still exuding a vague aura of menace. The manager would raise a hand in the mildest of acknowledging gestures, prompting the Bums to launch into yet another rendition of the song they’d fashioned in his honor.

The Cubs’ players were remarkably indulgent of misbehavior from any wayward fans, who, conditioned to see themselves as an active part of the team’s accomplishments, occasionally became a part of the on-field action.

On June 3, 1969, three men leaped over the low leftfield wall and made a dash for home plate. Nine more quickly followed them, setting off a mad, ping-ponging race across the Friendly Confines as park staff tried to corral the intruders. One fan headed straight for the pitcher’s mound, stopping to shake hands with pitcher Bill Hands and then dashing away. Another slid into second base and popped right back up, showing off evident practice. The security staff had the numbers, however, and they picked the trespassers off in ones and twos until just one was left.

The sole survivor ran for the low left field wall, just about twice his height from the base to the crown. Still, the slick ivy over the flat brick would have made it a very difficult climb…if not for the rope that had been discreetly lowered down from the seats above. Ten bleacherites heaved as the shirtless man scrambled up the rope, security officers practically snapping at his heels. He tumbled over the wall and disappeared as the crowd closed ranks behind him.

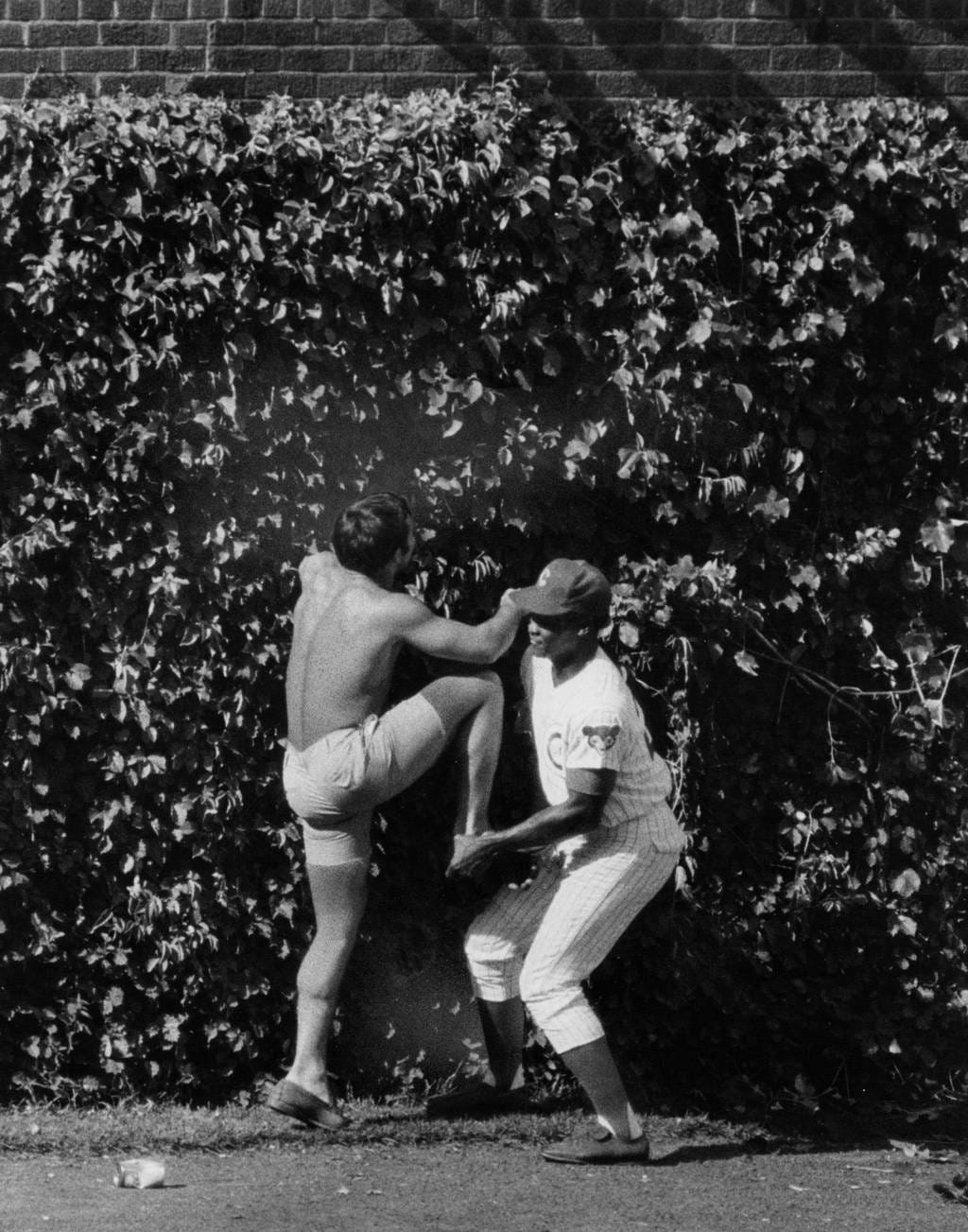

Every so often, practiced Bum cheerleaders standing on the outfield walls got too excited and fell the 12 feet down into the outfield, one of the shortest drops of any park in the major leagues. Rather than tackling them or leaving them to the onrushing attention of ushers and security staff, Cubs’ outfielders like Billy Williams and Willie Smith would lend a knee and a boost to a hapless fan, letting them scamper back up to safety before they could be captured.

Above, Cubs outfielder Willie Smith helped a fan avoid a $25 fine on July 13, 1969. We love everything about this photograph, including how perfectly it works as a flip-flop visual metaphor of the boost the Cubs’ players said the fans gave them.

By now you may be starting to get a sense of where the basket really came from. But the truth is, in the summer of 1969, from the Cubs’ perspective, all was well with their wonderful, eccentric fans. Mr. Hunky Moccasins up there was probably on the plane to Atlanta a month later, paid for by P.K. Wrigley himself.

But after August came September, and with September came the fall.

The last two games of the season were played with the NL East already decided and the Cubs already toast. There would be one last knife-twist, as Wrigley hosted the victorious New York Mets for a last, meaningless pit-stop before the Mets flew on to Atlanta to begin their playoff with the Braves.

To mark this embarrassing occasion, the bleacher crowds (what was left of them) leaned into pageantry, leading marches from their outfield haunt into and through the grandstands and to the very top of the visitors dugout, where they hung black and purple funeral bunting and prayed for a Braves’ victory.

The procession also visited the home dugout, where dozens of Bums and novice Bums paid homage to the risen Durocher, who was delighted to have something positive to reflect on. Flattery got the Bums everywhere with the Cubs’ manager, who reached up and shook hands with many. “These are some kind of fans,” he marveled. “They’re the best I’ve ever seen. Even better than Brooklyn.” A few years later, the Bums’ chants would call for his head.

Once the game ended and the season with it, the Bums took over Wrigley Field, gently tumbling over the outfield walls. They ran the bases, practiced their slides, and staged a sing-along around the pitcher’s mound that lasted an hour. Meanwhile, the Cubs’ organist hammered away at “Happy Days are Here Again.”

“The bloom began to fade from the Bums’ rose after that,” pitcher Fergie Jenkins remembered. Now that their powers of luck seemed spent, the Bums were newly exposed to resentful skeptics, and a reappraisal of the Special Relationship really began on that last day in 1969. Chicago Tribune writer Edward Prell had grit his teeth and put up with it all season, but no longer:

The Bleacher Bums should have been thrown out long before their disgraceful performance yesterday…They started making nuisances of themselves early this season, but were nowhere in sight when the Cubs were losers a few years back…The Bums got into action in the eighth and showed utter disdain for the rights of other fans.

Prell ended with a question that read more like a challenge to the Cubs organization: “Will the Bums be welcome next year at Wrigley Field?”

Philip K. Wrigley seemed to be asking similar questions (of himself). In a postseason postmortem interview, the Cubs’ owner said:

Naturally I’m disappointed, but after so many years of disappointment, I’m used to it. It was a good year and we gave the fans a lot of excitement—but they may have become too excited. They idolized the players and our players suddenly became heroes, celebrities in demand. I think it had a lot to do with their failure to win.

Wrigley’s comments boded ill for any future sponsored trips to the Sun Belt. On that note, the Cubs and Bums went on a needed break, hibernating apart during a long, rueful winter.

At first, the spring seemed to promise renewal. Despite temperatures in the low 40s, people slept on the street to buy unreserved tickets to the 1970 Cubs’ home opener, on April 14. Not even the team’s recent, spectacular collapse could overcome Chicago fans’ notoriously poor short-term memory.

“I never saw so many people lined up,” Durocher said.

There were at least 10,000 out there when I got to the park at nine this morning. I couldn’t believe it. They were standing all around this damn ball park. I said, ‘where the hell did they come from?’ And there must have been a lot of sick grandmothers because many of them were kids who should have been in school.

The excitement built as the crowd waited for the ticket windows to roll up. When they did, a dangerous surge towards the front resulted in several broken bones. A few people fainted and had to be bodily passed back to the rear. Something had changed.

The Cubs, for their part, came on strong behind Ken Holtzman, who pitched a complete game, surviving a dicey ninth-inning rally by the Philadelphia Phillies, who scored four runs but needed five.

Despite the on-field success, ugly and dangerous energies had overridden the skewed exuberance of the year before. There were numerous fights in left field, rolling disturbances that kept 200 ushers and 30 security officers running ragged. One usher was knocked down and nearly trampled. Other usher injuries included chipped and knocked out teeth, a fractured thumb, and severe cuts and bruises. Many of the ushers were kids themselves, working a part-time job while going to college. They’d use the alcohol confiscated from insufficiently-sneaky fans to throw their own parties. This was not what they’d signed up for.

Once Ken Holtzman coaxed that last elusive out from the Phillies, hundreds of people, perhaps as many as a thousand, burst through usher cordons along the first base line and spilled onto the field. One celebrant fell awkwardly out of the right field bleachers and had to be carried away. When this kind of thing happened in ‘69, it was inappropriate, but the fans were there to celebrate, or at least, to have a relatively innocent good time, base stealing and mound-singing, etc.

In 1970, people from the crowd (we must retract the “fan” descriptor for this part) attacked both the staff trying to restore order and even the Cubs’ second baseman, Glenn Beckert, who was assaulted by a group of three persons who had decided they wanted (and deserved) his cap. Beckert resisted, and the group tried to wrestle him to the ground. His chief attacker was a young person “with a wild look in his eyes.” “He acted like he wanted to claw at my face,” Beckert said. “Earlier I was hit by a thrown orange as I was waiting in the batters’ circle. But that was nothing compared to this boy. He was spooky.”

According to the Chicago Tribune, the level of antagonism between some of the spectators and the authorities got so bad that one usher took off his blue uniform jacket and “adopted a boxing stance reminiscent of John L. Sullivan,” daring some especially abusive fans to come and take him on.

The Cubs quickly called for police presence inside the ballpark, a request that was denied on the basis of an antiquated policy decision that prevented police from working inside the city’s stadiums2.

The rule didn’t make a lot of sense and after April 14, the city’s mayor would rescind it. In the meantime, though, none of the Cubs’ staff could make arrests, and the police wouldn’t step in, so ultimately no one was arrested that day. The police superintendent, James Conlisk, was quoted as saying “[The organization] might be happy to see the same boisterous crowds in July, especially if the Cubs aren’t doing well.” Found the White Sox fan.

Breaking down this opening mess, the Tribune made sure to emphasize an important point with a six-word, one-sentence paragraph:

The Bleacher Bums were not involved.

The Bums had become so well-known in the media that the regular reporters could spot them in any crowd, helmets or not. And certainly the modus operandi didn’t fit. Not a Bum in the city would take a swing at Glenn Beckert. Most would have tried to take the punch on his behalf.

The Sporting News correspondent echoed the sentiment of his colleagues from the Tribune: “The original yellow-hatted group that is noisy and likes to do its thing, but had no hand in the ugliness.” To make that point, he even had a quote from a Bum whose day had been ruined: “[Those people] were animals,” said the anonymous member. “Some of those kids wear the hats and try to look like Bums, but they’re just plain bums.”

After April 14, the real Bums moved quickly away from hats, which were too easily copied (and too easily picked out in a crowd). They switched to official membership cards.

The next day, Ernie Banks had a usual word of cheer, but this one carried a note from what would soon become a primary motif of 1970s baseball. “There ain’t gonna be no rioting in the friendly confines of Wrigley Field today!” Mr. Cub sunnily promised, and he was right. On a cold and windy day, Banks was the warmest part of the experience. The weather drove down attendance and exuberance, with just 7,120 in the stands.

People were still trying to process what had happened the day before, without much success.

“You can see the troublemakers aren’t here today,” one guard observed. “Maybe they went back to school. The people who fought the ushers yesterday didn’t come out here to watch the ball game. They were the kinds who were just looking for trouble.” Yes, but why?

No one seemed to know. Fergie Jenkins later mentioned in passing that he thought “an anti-Vietnam War group” had been behind the storming and assaulting, but didn’t elaborate.

What had so transformed the tenor and character of Wrigley’s crowds in less than a year, going from chants and songs and cheers (and yes, the occasional soft-bodied missile) to riot, violence, and general disorder? It was, and remains, a mystery.

“I don’t know what was wrong with the opening day fans,” Vice President and General Manager John Holland said. “I don’t know what came over them.” Nor, in fact, did he much care.

The old-school general manager had never been comfortable with the team’s increasing coziness with the fans. When the players tried to get the Bums’ leadership on the team’s charter flight to Atlanta the previous August, Holland vetoed the idea and insisted all Bums fly coach. The unexpected difficulties on April 14 provided Holland an opportunity to correct what he (and now Wrigley) saw as a well-intentioned mistake, and he earnestly set to work.

Three days later, on April 17, the Cubs announced a series of security changes, collectively representing “the most comprehensive move ever undertaken by any sports organization for crowd control.” Among them:

Standing room had been eliminated in the bleachers, taking ticket capacity from 4,000 to 3,200

Vendors would no longer sell beer in the bleachers, only at concession stands

A new, zero-tolerance policy for selling alcohol to minors

A closed-circuit television scanning system would be installed throughout the park (“the same type of camera system used in banks”)

Holland seemed like Big Brother on Christmas morning after discovering Santa had gotten him all the tools of repression he’d asked for:

Undoubtedly, the most effective thing will be the introduction of these video cameras. They will enable us to pinpoint where disturbances are and also the troublemakers involved.

The lenses of these cameras will be able to zoom in so that we can positively identify whoever is involved. And that will help us in court to prosecute them. The rowdies will no longer be able to insist, ‘It wasn’t me.’

The splashiest change would have a measurable impact on baseball at Wrigley Field, for the Cubs, visiting teams, and fans alike. A 42-inch wire-mesh fence would be added to the top of the bleacher wall and set at an angle. In the initial design, the fence was installed at the top of the outfield wall and rose up, obstructing the view of the first two rows of bleacher seats, but it was ultimately installed several feet lower, closer to the field, so as to remain out of view, where it remains today.

“We don’t want to change the home run trajectory any more than we have to,” Holland said. “That’s one of the reasons we’re going to [slant] the screen out into the playing area. Furthermore, the umpires shouldn’t have any more problems with fan interference on questionable balls that hit the top of the wall. Everything that drops in the park will be in play.”

“Sounds good, no notes,” came the reply from first-year National League president Chub Feeney, or some similar feedback. Feeney and the National League waived a rule prohibiting changes to the field dimensions during the season, despite the fact that this particular change would have significant implications for scoring.

It was a substantial change, but “we’re determined to stop this rowdyism so that enjoyment of the game will not be ruined for the great majority of decent people who come to the ballpark,” Holland said. “We hope the screen will prove to be a deterrent to the youngsters who have been jumping on the field.”

The basket was not added to catch what Cub fans threw. It was added to catch Cub fans. Or, more precisely, to deter them before they required catching. Trespassers could no longer expect a soft-hearted outfielder to bail them out, and a rope journey up and over that obstacle would require Batman-levels of physical conditioning.

Holland’s reforms were the equivalent of delivering divorce papers to the common bums in the outfield bleachers, but one minor item, barely noted in the list of bigger-ticket capital asset purchases and ordinance changes, specifically targeted the formerly-sponsored Bleacher Bums cheerleaders.

Henceforth, standing in the bleachers, including on the top of the outfield walls, was banned.

“Keeping standees out of the aisles will insure freedom of movement for security when trouble arises. And anyone going out for a beer will still have a seat when he returns,” Holland said. In other words, the Bums would need to take a seat or face the consequences, same as everybody else.

The outfield baskets were installed between the end of April and early May while the Cubs were out of town. It took a few games before the park’s notorious winds turned outward enough for a slugfest, but on May 10, none other than the Cubs’ future Hall-of-Fame outfielder Billy Williams had the honor of hitting the first “basket homer.” Also hitting home runs that day were four members of the visiting Cincinnati Reds, including Pete Rose, whose two-run shot in the ninth inning cleared the strange new contraption along the wall and ultimately won the game.

It was an infuriating outcome, perpetrated by the vilified Rose, but the only thing thrown onto the field in response was the home run ball itself, a Wrigley tradition started by the Bleacher Bums, back in those golden days of ten months earlier.

We hope it has been a very happy Opening Week for all of you who practice!

We’ll probably come back to the Bleacher Bums in the future—we’d really like to bring you the full story of that Atlanta series at some point. So much to get to!

Until then, we’d love to hear from those of you with Wrigley Field bleacher memories to share! None of our reader-shared anecdotes thus far have disappointed, so feel free to add yours.

We’ll be back next Monday to start a new (!) segment, one we know you’ll enjoy, and we’ll probably have another piece later in the week to show off the concept.

Coming on April 8: “A Bevy of Tearful Departures”

Rose’s choice of euphemism (“the goat run”) calls back to the nickname of a similar feature in his first ballpark, Cincinnati’s Crosley Field, but was never actually used for the fence at Wrigley.

My favorite part of this great story:

"Once, late in the season, the third baseman (Ron Santo) walked out to left field on a bad knee to inform the left field fans he wouldn’t be starting that day because of said bad knee and that he was sorry."

Gosh, ya just gotta love baseball!

I remember seeing Bill Veeck camped out in the leftfield bleachers at Wrigley Field, in the mid-1980’s - shirtless - had to be pushing 80 at that point - I don’t recall him wearing a Bleacher Bum hard hat, but those had been retired years earlier.