The Disallowed - Part 1

"Deja vu is usually a glitch in the Matrix...it happens when they change something."

During a 2024 Spring Training game, Ángel Hernández, an umpire with an inconsistent strike zone and particularly thin skin, ejected St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Lance Lynn twice. The first hook was for arguing balls and strikes, and Lynn probably earned that one, being himself something of a grouch. When Lynn retreated to the bullpen to finish his necessary pre-season throwing, Hernández had another official go out and re-eject the pitcher for having not left far enough, creating yet another spectacle.

Wondering for the umpteenth time how in the world Ángel Hernández still has his job, we tried to think of all the active umpires we could name. It was not a long list, and Hernández was high up, with CB Bucknor lurking just below. As with anything else, the more problematic umpires receive disproportionate attention.

In fact, most of us spend most of our baseball time watching umpires work with quiet competence and discipline, even as we fail to notice them. There are innumerable examples of umpires acting nobly, bravely, and with poise and dignity as they try to hold things together while the ballpark goes mad around them, and we expect they’ll be heroes more often than villains in our work, or at least sympathetic characters. We expect to say this often of umpires at Project 3.18: “They did their best, in a bad situation.”

But every so often, you find an umpire who just wants to watch the world burn.

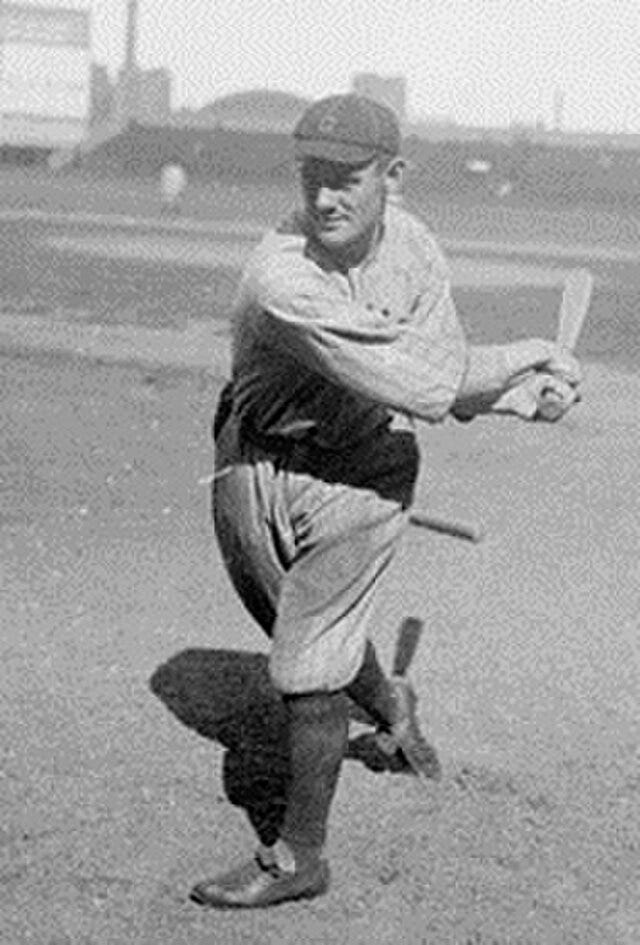

In 1920, Cleveland third baseman Ray Chapman failed to see an errant pitch stray up and inside until it was too late. The ball struck him in the temple and Chapman died several awful hours later.

The pitch that killed Chapman was thrown by the New York Yankees’ Carl Mays, but most observers felt the beaning was accidental. Some of Chapman’s last words were used to make this point, spoken as he was helped off the field, the seriousness of his injury not yet evident: “Tell Mays not to worry.” He lapsed into unconsciousness soon after.

Carl Mays was a member of the order of spitballers, a group of pitchers who regularly and openly used their saliva and other substances to make thrown pitches do unpredictable things in flight. The spitball’s erratic movements helped it miss bats, but throwing them was something of an art to get right, a practice of controlling chaos. This legitimate pitching methodology was made viable by the fact that in the Deadball era, major league baseball games used a single baseball for as long as possible, even as the ball took on more dirt, damage, and who knows what else.

This became the prevailing theory of why Ray Chapman failed to bail out of May’s errant throw: in the fading afternoon light at the Polo Grounds, a baseball increasingly discolored by Mays’ ministrations and prolonged use moved so erratically that Chapman failed to track it or even spot it plowing inside.

Chapman’s death shocked the baseball world, and while Mays was held mostly blameless, his chosen method of pitching ended up taking the fall. The spitball had already been on its way out—in 1919, baseball adopted a new rule limiting the number of spitballers to two per team, both of whom had to be declared. In the aftermath of Chapman’s passing, baseball went further, requiring umpires to remove dirtied or discolored balls from play immediately, and making the “spit” ball illegal with a rule that said pitchers could not bring their hand to their mouth while on the mound and in the act of pitching. If a pitcher did that, the umpire would call a ball and issue a warning. A second offense would result in ejection, in theory.

Reluctant to penalize veterans who’d built their careers on what had been up until that point been a perfectly legal practice, a group of 17 pitchers known to be dedicated spitballers were grandfathered out of the new rules. This was, the league would tell any future widows, the fairest way to handle it. Fortunately it never came to that, and Burleigh Grimes, the last sanctioned spitballer, retired in 1934.

Ray Chapman remains the only major leaguer ever to die in the line of duty. He lies at rest in Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland, Ohio, and more than a hundred years later, baseball fans have not forgotten him. Hopefully we never will.

The spitball and its relatives did not retire with Burleigh Grimes, however. They remained in constant, covert use, in every decade right up to and through the present day.

Enforcing the spitball ban depended on an umpire spotting a pitcher touching their mouth, so pitchers just stopped doing that. Instead, they began secreting various fluids, oils, and tacks in all manner of creative places on their uniforms and bodies. Discreetly catching these creative and determined cheaters proved nearly impossible, so much so that for several decades, umpires made only halfhearted attempts to try, and the practice quietly flourished, particularly among pitchers whose pure stuff didn’t quite play in the major leagues.

And then came 1968, the Year of the Pitcher, when offensive output cratered and the group of batters able to go toe-to-toe with big league pitchers dwindled alarmingly. As baseball scrambled to fix its broken offense, umpires were urged to crack down afresh on “doctored” pitches and the pitchers who relied on them. Their next inquisition would start (and end) at Wrigley Field on August 18, 1968.

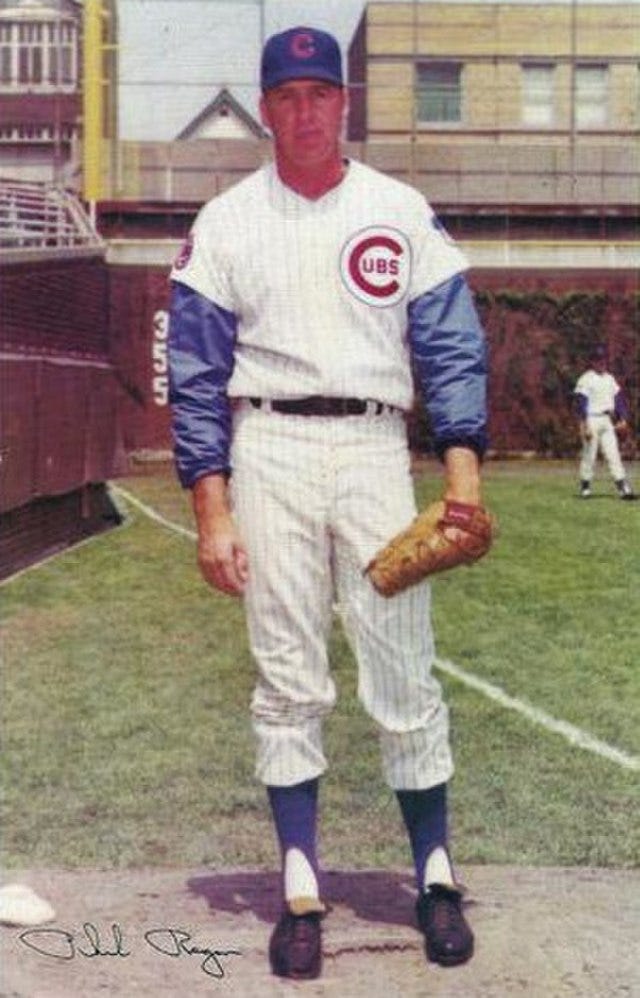

Signed by the Detroit Tigers in 1960, Phil Regan, a native of Byron Center, Michigan, had long had what one commentator described as “a rather ugly, stiff-armed delivery, the opposite of poetry in motion,” though his skills were good enough for an up-and-down career that took Regan from Detroit to Los Angeles. Regan had broken into baseball like almost every pitcher of his era did, as a starter, but with the Dodgers he shifted to relieving, where he began to flourish.

In 1966, Regan made his only All-Star appearance and earned his terrific nickname: “the Vulture,” for his uncanny ability to enter close games with his team behind or tied, only to see them pull ahead, granting him the pitcher win. That year he went a remarkable 14-1 despite not starting a single game. 1967 brought a step back and mixed results, and early in 1968 he was traded from the Dodgers to the Chicago Cubs.

Long before Regan arrived in Chicago, he was rumored to be among the pitchers doctoring some of their pitches. Sy Burick, the same columnist who critiqued Regan’s “stiff-arm” delivery went on to say (with the removed air of a man who understands how libel laws worked) “...it has been suggested that his delivery had been aided and abetted by ‘foreign substances.’”

Regan, Burick continued (carefully, oh so carefully) “…has been accused of using saliva, often generated by chewing a kind of lozenge whose basic ingredient is the spit-inducing slippery elm. It has also been suggested that he makes baseballs take unnatural dips by secretly rubbing Vaseline on them, obtained from a hidden source on his person.”

Such illicit methods were regularly called upon by pitchers who felt they needed an edge. Larry Shepard, then manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates, told Burick he could name 15 pitchers off the top of his head who doctored the baseball, and that was just in the National League. It is extremely likely Regan was on his list.

As a Cub, Phil Regan regained much of his earlier form. He became the most essential piece of the team’s relief corps. Unlike the closers of today, tasked with only going the last one or two blistering innings with the team ahead or at least tied, “firemen” like Regan were called into games whenever a starter was in trouble and the game seemed salvageable. Once brought in, they were expected to go the rest of the way. On August 11, 1968, for example, Regan relieved the Cubs’ starter, Ken Holtzman, in the eighth inning of a game against the Cincinnati Reds. The Reds managed to tie things, the game went into extras, and Regan just kept pitching. He ended up throwing eight innings, more than Holtzman, and the Cubs eventually won in the 15th.

31 years old, Regan was having a fine year in 1968, the second best of his career. He was 10-2 at that point and would finish with a career high 25 saves and an earned run average of 2.27, becoming the most trusted late-inning weapon of the Cubs’ manager, Leo Durocher, on an increasingly-competitive Chicago squad.

As he was on August 10, during a game against the Reds at Crosley Field in Cincinnati. When the Cubs’ starter, Joe Niekro, began to falter, Durocher replaced him with Regan in the middle of the sixth, a typical deployment. Soon thereafter, the Cubs pulled ahead, Regan held on and earned yet another win. The last batter he faced in the bottom of the ninth with the bases empty and the score 8-5 was Pete Rose, who grounded out to shortstop. Game over, Cubs win.

Walking off the mound, Regan said something to Rose, the type of communication we might refer to today as “chirping.” We don’t know what specifically he said, and Rose said he didn’t know, either, but whatever your imagination plugs into the context will probably be pretty close. It was enough for Rose to charge at Regan as he walked off the field and throw a running punch in his direction. Both benches cleared and the two were quickly separated. The game already ended, there was nothing to eject anyone out of, so it was over. Besides, boys will be boys, sometimes they attack each other, etc.

“He said something to me and I wanted to know what it was,” Rose said of the incident. It was, in his estimation, “a minor confrontation. One swing and nobody connected.”

According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, spitball pitchers had long been “a mental block” in the “happy-go-lucky” makeup of Pete Rose. The altercation with Regan was, Rose said, the first time in his major league career that he’d picked such a fight, and that it happened with a spitballer did not surprise him. “I hate to go to the ball park when I know one of ‘em is going to pitch. They’re cheaters.”

And this was an essential ingredient of the spitter’s magic. Whether Regan threw one or not, whether he threw any at all, having batters think he did created an advantage he could exploit with his legal arsenal. The best spitballers of the modern era were masters of misdirection and manipulation, throwing far fewer wet pitches than their early ancestors while simultaneously making hitters see crimes and cheats everywhere.

Pete Rose, a man of the deepest blacks and whites, found this liminal and uncertain psychological space deeply frustrating, and this represented a weakness in a player known to have few. The next day, the Enquirer reported that Leo Durocher, long a master in the arts of psychological warfare, had needled Rose during at least one of his two at-bats against Regan, calling from the dugout, “Hey Petey, can you hit the spitter? You’re going to get it.”

Even if the manager knew for a fact that Regan had never touched Vaseline in his life, that would not stop Durocher from using an imaginary greaseball to torment opposing batters. A batter guarding against the threat of a Bugs-Bunny pitch would end up watching as a bone-dry, mediocre fastball sailed past for strike three.

The Reds and Cubs reunited a week later, at Wrigley Field, for a four-game set which culminated in a Sunday doubleheader on August 18 and two games that Pete Rose would frequently recall as among the most memorable from all 3,562 in which he played.

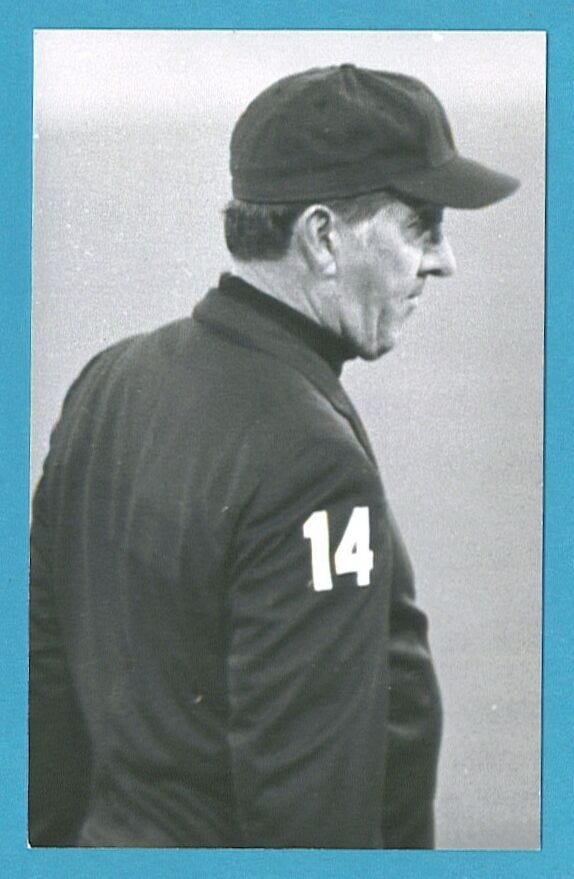

The umpire behind the plate for the day’s first contest was Chris Pelekoudas, 50 years old, small in stature, proudly Greek, and in his eighth year as a National League arbiter. Pelekoudas had a crusty, tough-as-nails reputation, but was not known as a showboater or any kind of zealot. He had made the rounds, working 3,000-some minor league games across four minor leagues before he got the call to the big leagues in 1960. He was secure in his job and in himself; in retirement, Pelekoudas would say that what he missed most were the boos of the fans when he made what he knew to be the correct call.

Like Rose, Pelekoudas didn’t care for shiftiness and prized straightforward combat. He spoke mainly in crisp, declarative barks, as when he summed up the state of managers in 1977: “They couldn’t work their way out of a wet paper sack. They have relievers for this and that, there’s a specialist for everything!”

We know that Pelekoudas and the other umpires of the four-man crew working the Cubs/Reds series had discussed Phil Regan, his reputation for using “illegal pitches,” as Pelekoudas would call them, and they probably also discussed the business with Rose in Cincinnati the week prior. Later, Pelekoudas wanted to make sure that no one thought what happened that day had been impulsive or accidental:

The umpires as a team had discussed this thing about Regan before the game and decided to bring it to a head.

Why they chose this third game of the series and not the first one “to bring it to a head” is unclear. Project 3.18 alum John Kibler worked behind the plate during the first game and Regan’s innings proceeded without drawing complaint from any party. At this point, Kibler was a junior man, only three years in. Maybe the crew wanted the more senior Pelekoudas to do it. Or maybe he volunteered.

The Cubs struck first in the contest, scoring one run off of the Reds’ starting pitcher, George Culver, in the first inning. The Reds came right back with one of their own, helped by an error from Cubs shortstop Don Kessinger in the second, and added another in the fourth via a Tony Perez home run. After six innings, his team down 2-1, Leo Durocher came to collect the Cubs’ starter, Rich Nye, and replace him with Phil Regan.

Once Regan entered the game, Pelekoudas did not wait long to spring his vulture trap. Before he threw a single pitch, he spoke to Regan and warned him against throwing any “illegal pitches.” It is unknown how the pitcher responded to that.

The inning began and Regan built a 1-2 count on the Reds’ lead-off hitter, Mack Jones. The pitcher made his next offering, and Chris Pelekoudas stopped the game and walked out to the mound, declaring that Regan had just thrown an illegal pitch.

Out came Leo Durocher. The manager was understandably not happy when he learned what the issue was, but Pelekoudas was within his rights to make such a determination. Durocher stalked back to the dugout. Under the rules, the count should have been 2-2, the illegal pitch having been counted as a ball, but as everyone settled back in to resume play, Pelekoudas gave the count as 3-1. The Cubs’ catcher, Randy Hundley, jumped back up to argue. Durocher had barely sat down but was now back out, his face two or three shades redder. After some discussion, it was established that Pelekoudas had gotten mixed-up. The party agreed that the count was 2-2, reflecting the illegal pitch as ball two. Sorting this out had taken a full five minutes.

Regan threw another pitch, which Jones fouled off. Jones then hit a fly ball to center field which was caught for an out.

Except, it wasn’t.

Pelekoudas summoned Jones back to the batter’s box. Regan had thrown another illegal pitch, the umpire announced, and he “disallowed” that pitch and the resulting out. As such, Jones’ at-bat would continue, with a 3-2 count.

Under the rules, Pelekoudas should have ejected Regan right there, having warned him previously and now observing what he deemed another infraction. But the umpire ignored the rules. Later, he would be pretty honest as to why:

I warned him, and at first I decided to throw him out of the game when he threw the next Vaseline ball. Then I had second thoughts. I said, “To hell with him,” let him stay in the game and suffer. Every illegal pitch will be a ball. It’s up to me to decide whether he stays in or not and I thought this punishment would be more severe than throwing him out.

As long as he was going to defy me, he was going to suffer.

Say what you will of the man’s judgement (and oh, we will), but Chris Pelekoudas shot straight.

Leo Durocher stormed out onto the field again, screaming at the umpires, arguing the decision and the rules, which he knew intimately—Durocher often kept the rule book in hand while arguing with umpires, citing it chapter and verse like a traveling preacher in front of the parishioners he aimed to swindle. He knew a non-standard penalty when he saw one, and there was nothing the Cubs’ creative manager loathed more than an innovative arbiter.

Pelekoudas, now accompanied by crew chief Shag Crawford, headed to the mound to perform a direct examination of Regan’s person while Durocher observed. They asked the pitcher to remove his cap and they inspected it. There, according to Pelekoudas, “we found Vaseline inside his cap, and on his forehead.” Shag Crawford wiped Regan’s head, hair, and cap with a towel that Durocher himself provided and then improbably handed him the next game ball.

Pelekoudas explained to Durocher how he determined Regan had been cheating. Rather than finding any evidence of a substance on the ball or seeing Regan go to his mouth or anywhere else unusual before throwing, Pelekoudas had gone off the flight of the pitch: “A sinker spins when it breaks. And a ball with Vaseline on it breaks down without spin. I know an illegal pitch when I see one.”

Leo Durocher’s reaction to this logic model resulted in him at last being put out of his misery, oddly, by umpire Doug Harvey, the least-involved official on the crew. Since arriving in 1966, Durocher had already built a thriving cult of personality at Wrigley Field and after Harvey threw him out, the bleachers erupted in petulant wrath, dumping all manner of debris onto the warning track, adding further delay while that was cleaned up.

Not to be excluded, the Cubs’ bench bristled with jeers and epithets, and crew chief Crawford, finally hearing enough, chose diminutive reserve outfielder Al Spangler to be sacrificed, the game’s second ejection. Spangler leaped off the bench and charged Crawford; such was his fury that it reportedly took Cubs coach Pete Reiser and four of Spangler’s teammates to restrain him.

Keeping muted tabs on all of this was the Reds’ manager, Dave Bristol. When he learned what was happening, Bristol found himself mildly agreeing with Durocher that a cheating pitcher should be ejected, but seeing something very strange playing out between the umpires and the Cubs, he fell back. “I didn’t want to antagonize the umpires too much, though. We were ahead, and we were getting the best of it.” The Chicago fans thought so, too.

After an enormous 30-minute delay, play resumed with Mack Jones and his new lease on life. His at-bat would continue in a changed ballpark, now a miasma of indignation and remarkable uncertainty. There was a wild card squatting behind the catcher and he’d revealed himself. Under Pelekoudas’ oversight, anything could happen next in this game, but what would?

Nobody had any idea, and they were all still wrong.

Thanks for reading the least crazy half of “The Disallowed.” We’ll be back next week to finish it and we promise there will be at least one thing that you’ll accuse us of making up. Nope, all true. Didn’t even have to embellish.

Coming on April 22: “The Disallowed - Part 2” - Retirements; Forced and Otherwise

Thank you for reading and the words of affirmation. ALWAYS appreciated.

I'm enjoying the bejezus outa these tales. Thanks. Please keep it up.