The Folsom Game

For more than four decades, a dedicated group of local heroes brought major league baseball inside a notorious California penitentiary.

Welcome to Project 3.18, a free weekly publication where a fan-first writer tells strange and surprising stories from baseball history and culture.

On February 8, 1942, a baseball game featuring two very talented groups of players, some of them major-leaguers, was delayed. The visiting team had arrived on time, the weather was clear and fair. Given the Northern California setting, an earthquake was a possibility, but the actual cause was even stranger.

This game—played inside Folsom California State Prison—was delayed for two hours on account of a prison break.

Elvia “Doc” Mead, 43, originally of Los Angeles, was the brains behind the escape. Mead was either convicted of first degree murder or robbery, which seems like a pretty big discrepancy. Either way, he was doing a life sentence at Folsom. The second escapee was Phillip Gardner, 35, also of Los Angeles, doing “five years to life”—for burglary.

Taking advantage of the distraction generated by a major event on the prison’s social calendar, Mead found a way to cut through a metal fence and slip by three concentric rings of guard surveillance to escape the prison grounds.

Mead jumped into a manmade canal connected to the nearby Folsom Dam, swimming across the treacherous, fast-moving water. From there he had to scramble 130 feet down a rocky and perilous embankment to the American River. To help manage this Mead had fashioned a rope made of knotted socks, but he had apparently underestimated the distance and the rope ended before he reached the bottom of the steep slope. He skidded the rest of the way, injuring his leg.

Back inside the prison, Gardner stared at the hole in the fence for a long time before he found the “courage” (is that the right word to use in this context?) to crawl through. He survived the canal and clambered out and helped himself to Mead’s rope, still secured at the top of the embankment. Gardner was trying to make his way past the final guard perimeter near the prison’s Tower 14 when he was caught skulking behind a pile of rocks. A guard informed Gardner he had a rifle trained on him. “Come out or I’ll fire.”

Mead got further, picking his way south along the American River as the prison staff began a manhunt. Their break came an hour later when three teenagers from nearby Orangevale spotted a “mysterious man” in a natural recreation area a few miles south along the river. The boys had come to the Mississippi Bar (as in sandbar) to hunt blue jays1, but when they spotted a man resting by the water’s edge in what were obviously prison pajamas they put two and two together and went to find a guard.

The injured Mead was probably waiting for the inevitable when the boys spotted him. He was quickly apprehended and did not put up a fight. Some later accounts of these events mistake the Mississippi Bar for the kind of bar that serves drinks. It would be a much better story if Mead gave up on his flight for freedom at the first prospect of a cold beer, but as usual you only get the facts from us here at Project 3.18. Mead didn’t get any alcohol before being recaptured, but maybe he saw a blue jay.

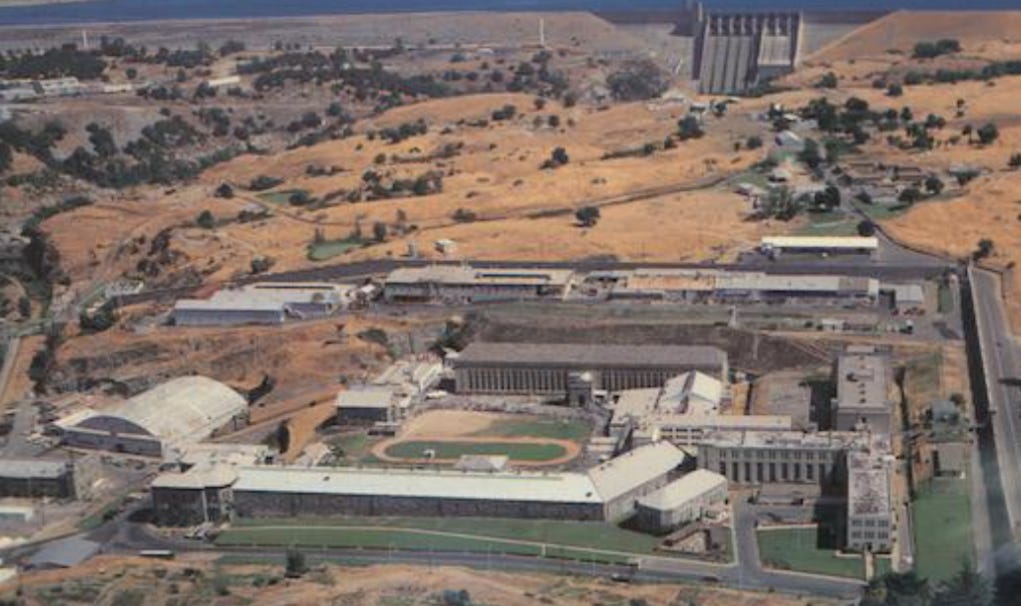

Folsom California State Prison first opened its solid steel doors in 1880. It was the second mass incarceration facility built for the state, after San Quentin. The prison land was donated by a family who made a deal with the state to use convict labor in the building of a hydroelectric dam across the nearby American River. The facility was built within the Folsom city limits but when the prison received its own post office in the 1890s the mailing address was affixed to nonexistent city: Represa, California. “Represa” is “dam” in Spanish.

In those early years the conditions at Folsom mirrored those of Northern California during and after the Gold Rush, with human comforts being an afterthought at best. As the state grew up so did the people running its prisons, and reformers promoted humane conditions that would better prepare inmates to lead productive lives upon their release.

Folsom had organized baseball as early as 1894, when a notoriously strict but progressive warden named Charles Aull organized several intramural teams inside the prison, with games being played on a diamond on the recreation yard on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays. A kind of “varsity” squad emerged from the four initial clubs, and this group had enough talent to challenge some regional competition. To avoid confusing their brand with any teams affiliated with the city of Folsom, the inmates called their club the Represa Eagles or the Represa All-Stars.

The baseball program got a true champion in 1913 when a former railway worker named William Ryan took a job as a guard at Folsom. Ryan, then 29, was a Sacramento baseball nut who seemed to draw endless satisfaction from arranging baseball and other sporting activities for the prisoners. He established a Fourth of July event that brought in professional athletes from basketball to boxing to tennis, and forged ties with the minor-league baseball team based in nearby Sacramento. Ryan soon became the prison’s first official athletic director.

By 1928 it was clear how much the philosophy of mass incarceration had changed. According to the warden at the time, recreation was the big thing:

We have a concert band of 36 pieces that would compare favorably with the best musical organizations in California. We also have a splendid twelve-piece orchestra. We have all kinds of track and field athletes, boxers, and wrestlers. The Represa All-Stars are considered one of the strongest semi-pro teams in Northern California.

Semi-pro teams were paid to play part-time. These teams were frequently organized by the company the players worked for; other clubs were backed by a professional or trade organization. The Folsom team was so good that it was periodically loaned out to fill out various semi-pro regional leagues when another team unexpectedly withdrew. Inserting the Represa club helped keep more than one league going, and the teams that made the trip inside Folsom often showed their gratitude by donating equipment to help the inmates refresh their well-used bats and balls.

The full-time Represa players sometimes ran circles around these weekend warriors. In 1926, for example, the Eagles’ record was 30-2-1. “Of course,” a local writer noted, “the Represa nine has the advantage of home grounds for all games.”

It was around the mid-1920s that Folsom athletic director Bill Ryan found a partner on the outside. Charlie Clark was a Sacramento baseball organizer, instrumental in setting up various teams and leagues in the region. Clark wanted to do something special for the talented players inside Folsom. His idea was use major-league and AAA Pacific Coast League players who lived in the area to play an off-season game against the Eagles. Clark found lots of players willing to make the trip.

The participants received no money for their appearance and they had to make their own travel arrangements—many carpooled. Some players signed up for the “adventure” of a visit inside Folsom’s four-foot thick walls, but many kept coming back for years, long after the thrill had worn off.

“Bringing a little light into an otherwise drab life is a good deed well done,” a 1941 editorial in The Sporting News said of the major league players helping out inside the prison, “and those who have lent their time to these games deserve merits in the scorebook of life.”

Charlie Clark stepped back from arranging the Folsom game in the late 1920s and the job went to his apprentice, a Sacramento businessman named Bill Morebeck. Other than playing baseball as a kid, Morebeck had no ties to the sport. He ran a flower shop and put the game together in his free time, a process which took about 10 months each year. Morebeck inherited Clark’s contacts and also greatly expanded them through his initiative and enthusiasm. In 1940 he secured the services of 24 major leaguers. The teams played as the “Bill Morebeck All-Stars,” and there were a decent number of actual All-Stars among them.

In 1941 he nearly got a San Francisco native named Joe DiMaggio to come. DiMaggio told Morebeck he wanted to participate but unfortunately didn’t arrive back in the area in time. In 1942 Joe’s brother Dom seems to have been offered up by the family as a consolation2 prize. That same year Morebeck heard from another big-name player, Brooklyn’s Dolph Camilli, who was in the area and interested in helping out, but apparently had no equipment to use. Morebeck found Camilli a suitable glove, shoes, and a uniform that fit.

That 1941 team was regarded as Morebeck’s triumph, representing “some $400,000 of baseball talent.” Earlier and later squads often made do with a “sprinkling” of name players but the 1941 crew even featured a future Hall-of-Famer, Cincinnati Reds catcher Ernie Lombardi. That team would have been good enough to beat any big-league club on any given day.

As for the Eagles, their best might have been the 1943 squad. On February 21 of that year Represa held Bill Morebeck’s All-Stars to six hits and beat them, 6-4. While World War II had already diminished the quality of the visiting teams, a number of enlisted professionals were made available from nearby Mather Field, a training base for the Army Air Forces. There weren’t nearly as many big leaguers on that club, but that surely did not keep the Represa players from cherishing memories of that win for the rest of their lives.

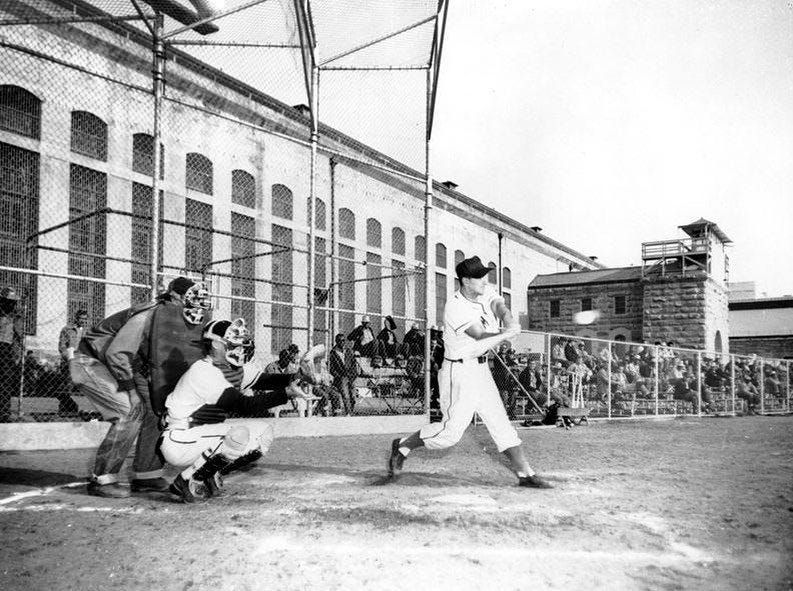

It is not clear whether Mead and Gardner’s escape delayed, interrupted, or ended the much-anticipated 1942 Folsom game. We tend to think it was the former. Baseball games at Folsom always began at 11:00 a.m., during the inmates’ recreation time, and there was a strict four-hour curfew. For understandable reasons, the prison officials did not tolerate the prospect of rain delays or having a yard full of inmates after the sun began to set. Whatever the exact sequence of events, the crisis ended quickly enough to allow seven innings to be played before the curfew time.

Morebeck’s All-Stars romped in the shortened game, scoring 24 runs. In some years it had been the practice to “loan” the Eagles a professional pitcher and catcher3 to somewhat level the playing field, but on this day the prisoners seem to have thought they had enough pitching, and clearly they were wrong:

Eddie Lake, a major leaguer unsigned that year, walked four times, got a hit in three official at-bats, and scored five runs in the leadoff spot.

Gus Suhr, who played in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia between 1930 and 1940, hit five singles in six-at-bats. Suhr was a dedicated supporter of the annual game, participating in at least 11 consecutive years.

Joe Marty of the Phillies was another regular participant, and he went 3-4. Marty was a “fan favorite” at Folsom. A few years earlier he had accepted an assignment as a major-league correspondent for the prison newspaper.

Dom DiMaggio was the biggest name among the players in 1942, a fact that did not stop the Sacramento Bee, which published a box score, from spelling that name wrong. “DiMago” got a hit in the game and his glasses make him easy to spot in a group photo:

The Eagles did pretty well at the plate, under the circumstances. The first pitcher they faced, Tiny Bonham (6’ 2”, 215 pounds, in case you were wondering) of the New York Yankees, would win 21 games that year. The other pitcher, Manny Salvo of the Boston Braves, would also have a good season. Both pitchers regularly took part in these games, and they may have been going easy on the prisoners, nearly all of whom got at exactly one hit off a big leaguer that afternoon, enough to secure bragging rights forever.

Neither the escape attempt nor the 24-5 final score kept those involved in the game from having a great day. Afterward the players were hosted and toasted in the prison’s officer commissary, which was much fancier than it sounds. Folsom’s grounds included significant plots of working farmland, and the postgame meal featured a bounty of farm-to-table delicacies.

A menu for the 1941 game lists ten courses, featuring dishes like “celery en branche4,” “young tom turkey with sage stuffing,” and “small club steak persillade.” Hopefully the players saved room for dessert, which included three different kinds of pie, all served a la mode on cedar planks.

Major leaguers had been playing inside Folsom for nearly 15 years, and no one involved would let a little thing like a prison break end that streak. Many of the players around those commissary tables would return in 1943 and regularly thereafter. There was something about the experience they found fulfilling, and it wasn’t just the pie.

Bill Ryan was promoted to Associate Warden in 1944. He eventually spent over 40 years with the men inside Folsom. When he started in 1913 the inmates wore black-and-white striped uniforms and there wasn’t much recreation beyond breaking rocks. He spent his life changing that.

Folsom could be a brutal place, and brutal things happened there. In 1937, a year after Ryan became the guard captain, a group of inmates rioted and took the warden, Clarence Larkin, hostage. In the ensuing chaos Larkin was stabbed to death. Ryan was stabbed seven times but recovered, in part thanks to an inmate who volunteered for an emergency blood transfusion.

After being released from the hospital Bill Ryan allowed himself two weeks off. Then he was back at work full-time inside the prison. Less than seven months after the riot Ryan and the new warden arranged for the AAA Sacramento team to come to Folsom to play the Represa club.

When Ryan retired in 1954 he was 70 years old and the oldest state prison employee. The inmates threw a “Bill Ryan Day,” gave him a custom-made rocking chair, and put on a vaudeville show acting out his life.

Writing a farewell salute to Ryan, a Sacramento paper observed that he had been at Folsom long enough to see prison theory “change from rock-breaking to modern industrial training and rehabilitation programs.” In fact these changes were made by people like Ryan, who refused to think of prisons solely as places of punishment. On his last day at Folsom he gave a speech to to the inmates and described the responsibility of his work:

There have been bad days and there have been good days. But when I think back on it, most of them have been good. It may, from your point of view, be hard to understand that remark. You may say it is another world for those of us who go home at night. You would be right. Nevertheless, let me say this to you: Going home at night doesn’t mean I forgot about this place. I did not. Wherever I was, your welfare, your well-being, your protection, and your interests, were always uppermost in my concern.

Rehabilitating incarcerated people is a game of failure, too. Many inmates would never get out, and others would walk through the gates only to return, again and again. But Bill Ryan knew that some of the men he met inside the prison had the potential to lead better lives. He believed sports could help give them the tools they’d need to escape for good.

The long odds and high stakes may have struck a chord with the players who kept coming back to play at Folsom. They all owed their professional lives to someone in their past who had given them a chance to show they could succeed despite errors, bad at-bats, cold stretches, and down years. Baseball was a hard and unforgiving game, but one hit at the right time could be all it took to win. Every chance mattered.

Is “hunting blue jays” a thing? Is this like birdwatching or like getting dinner? If you have ever hunted blue jays, please find us in the comments.

Dominic DiMaggio was a seven-time All-Star for the Boston Red Sox. If not for the prime years he missed while serving in World War II he might have been a borderline Hall-of-Famer. Only in the context of his own family might Dom be considered a consolation prize.

We know the convict team was happy with their catcher for the 1942 game, because a few months later he came up for release and the other players felt there was no one to replace him. They posted an ad in the prison newspaper, the Folsom Observer, asking law enforcement officials to be on the lookout for a new catcher. “He should have a fair knowledge of baseball and a keen batting eye,” the listing said. “Any sheriff who can dig up a likely prospect is requested to ship him to Folsom Prison.”

We think “celery en branche” might just have been celery sticks?

Paul, are you sure the Mississippi Bar wasn’t a group of attorneys?

Get Ebbets Field Flannels on the Represa All Stars cap STAT!