The Night They Caught Gaylord - Part 2 of 2

There was a rule in place to stop Gaylord Perry, but nobody had ever dared to use it. In 1982, somebody dared.

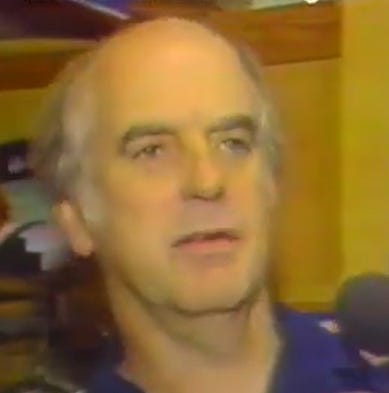

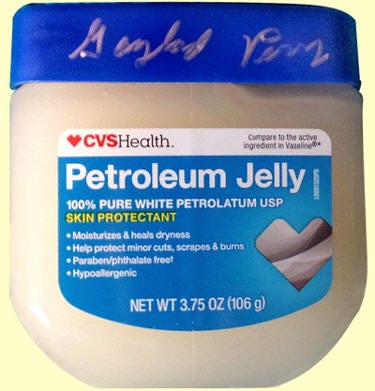

This is the story of how one of the most impressive streaks in baseball history ended. Until August 23, 1982, Gaylord Perry—the Sultan of Spit, the Viceroy of Vaseline, the King of K-Y—had never been ejected for throwing a loaded ball. But after umpire Dave Phillips saw his own fingerprint in one of Perry’s grease balls, the Mariners’ pitcher had been put on probation. One more whiff of Vicks VapoRub and he would face the wrath of the American League…and a small fine.

Here’s the first part.

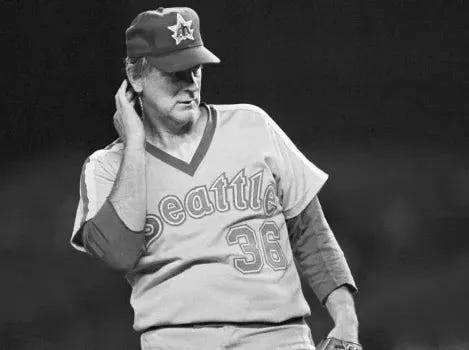

Gaylord Perry had been warned. Two innings later the pitcher was still on the mound, looking for his 305th win against the Boston Red Sox. But his stuff didn’t seem as good as it had been earlier in the game. In the sixth he gave up a walk and a run-scoring triple. Boston went ahead, 1-0. He was 42 years old; maybe he was getting tired.

In the top of the seventh, Reid Nichols, his earlier accuser, led off again, but this time there was no drama and Nichols grounded out. The next two batters singled and Boston had runners at first and third with one away. Whatever Perry had been using in the first half of the game was either gone or just stopped working. He was now in a jam.

He got second baseman Jerry Remy to fly out, but even Remy made solid contact. It was clear to the Mariners’ manager, Rene Lachemann, that the Red Sox had gotten a grip on Perry at last. He walked out to the mound to have a conversation about next steps.

“I breathed a sigh of relief,” umpire Dave Phillips recalled in his autobiography. Given the circumstances, a pitching change was called for, and no matter who replaced Perry, they would be much easier to deal with. Phillips got out his lineup card and prepared to cross out that dreaded name.

When he looked up, Lachemann had returned to the dugout, leaving Perry on the mound. The old pitcher had talked his way into one more batter.

“Rene came into our dressing room the next night,” Phillips told writer Kevin Czerwinski in 2021, “and I said, ‘I thought you were going to take him.’ Rene told me that Perry said he could get the out. I’m assuming that when he made that comment about getting him out he had a particular pitch in mind.”

Perry’s last chance was center fielder Rick Miller. The first pitch was a ball, but then Perry threw a pitch that invited Miller to take a big swing.

“The pitch was a doozie,” Miller said. “The best I’ve ever seen. It dropped down six inches and moved away a foot. There’s no way a baseball does that without doctoring or whatever.” Miller hadn’t even finished his follow-through before turning back to Dave Phillips, pointing at the ball, and making the traditional howl of protest. A chorus of similar howls emanated from the Red Sox dugout.

Phillips appeared to begin asking for the ball, but Essian, the catcher, had wasted no time and was already throwing it back to Perry for rapid decontamination. Phillips stood up and waved his hands to signal a time out. For the umpire it was the moment of truth. “Now either I can turn my head and say I didn’t see it, or do what I told him I was going to do.” He began moving toward the mound.

“It was clearly an illegal pitch,” Phillips recalled. “It looked like it was about an 88-mph fastball and about the time Miller swung the ball dropped straight down.” As he marched toward Perry he yelled four history-making words:

“That’s it, you’re gone!”

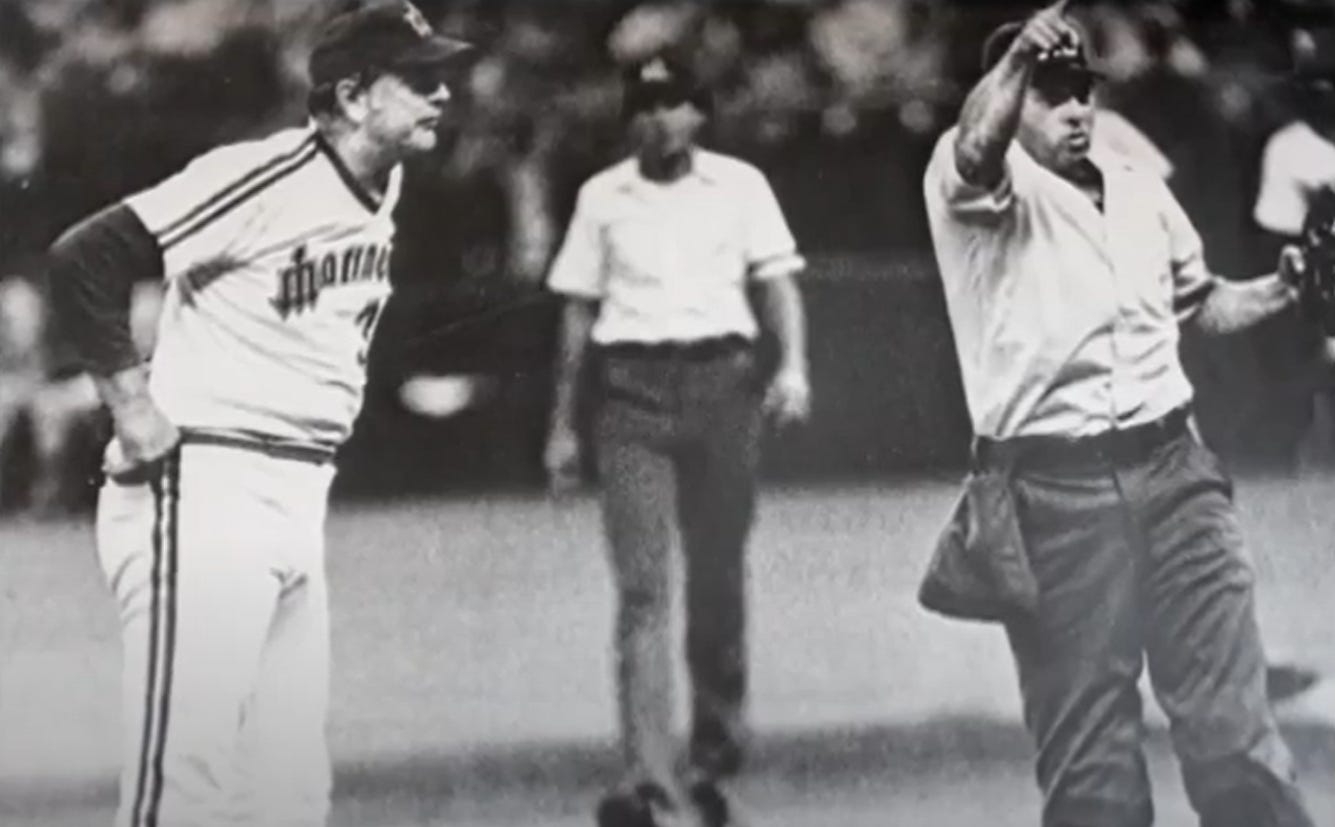

Perry raised his hands in the air, feigning confusion Or, perhaps, he just couldn’t believe it. Phillips doubled down, giving the pitcher the unmistakable gesture of banishment. Perry came off the mound looking like an old buzzard being shooed away from a meal.

Phillips said he looked embarrassed, “like a deer in the headlights.” That’s hard to say, but Perry must have been confused. He and the umpires always played their little games of cat-and-mouse, each side putting on their own show, but for most of 20 years there had been an unspoken understanding. The fans came to see Gaylord Perry pitch; they didn’t come to see an umpire throw him out.

Phillips remembered that the fans in the Kingdome, 11,700 of them, “let me know how they felt.” The field was awash in boos. “But I knew I was right. There was absolutely no doubt in my mind.”

Lachemann came out to argue, probably regretting his earlier deference to Perry, who had more time in the majors as a pitcher than Lachemann had as a player, coach, and manager combined. He instinctively put himself between his pitcher and the offending umpire, but there was no need. Perry seemed to be taking it rather well, and soon he was on his way to the Mariners’ dugout.

As he headed there, the crowd’s boos turned to cheers. They knew what they were seeing. This was July 17, 1941, the day Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak ended. It was June 8, 1968, the day Don Drysdale allowed a run after a record 58 and 2/3 scoreless innings. This was history.

The people rose to give Gaylord Perry a standing ovation for being ejected. Just before he disappeared into the dugout, the pitcher doffed his cap and waved.

Phillips was already thinking about the bright lights of the television cameras he’d have to face after the game, but there was more baseball to play. The Mariners scored three runs in the seventh to take a lead, but Reid Nichols, the back-up outfielder who’d initiated Gaylord Perry’s downfall, hit a go-ahead two-run home run and then threw out a runner at home plate to kill a Mariners’ rally and preserve Boston’s 4-3 victory. We don’t know much about Reid Nichols’ playing career (he also had a lengthy run of success in player development) but we have to assume the night of August 23, 1982 is pretty high up there.

In the press gaggle he’d been dreading, Phillips, slightly wild-eyed, did not come across like an umpire who enjoyed attention: “Believe me, it’s a whole lot easier when you don’t have a situation like this. An umpire would rather go through a game without any problems, but that’s not always the way it happens.”

“In our judgement it was definitely an illegal pitch. And not only did I know that it was an illegal pitch, everybody that’s out there that has anything to do with baseball knows what it was. The ball came in and the bottom fell out. He went two innings without throwing it, then he got into a jam and he went to it again.”

Phillips told reporters that in the fifth inning he’d found a “foreign substance on the ball,” the one Reid Nichols had wisely requested be checked. Asked what Perry had been using, Phillips said, “I’m no chemist, so I don’t know what it was, but the ball was extremely slippery.”

Listening to Phillips, we don’t get the sense that the umpires saw Perry as a nemesis they were eager to bring to justice. Instead, they seemed to see him like a third rail. While never said directly, you get the feeling the officials had decided—or been told—that avoidance was the best way to handle him. Keep him honest (as much as possible), keep him in the game, but above all, keep things moving.

“I feel Miller has every bit as much right to the field as Perry,” Phillips said. “The game’s supposed to be fair. I wasn’t looking to be a martyr. I was trying to do what was right. And if I hadn’t, the Red Sox had every right to be screaming at me.”

In the Mariners’ clubhouse, Perry addressed the media, as he always did. An innocent man has nothing to hide.

“Was it a forkball?” a reporter asked him, probably with a straight face.

Perry shrugged. “It was just…something that sank,” he said, looking off into space. “[Phillips] just wanted to stick it to us and that’s what he did.”

The pitcher was impassive as he methodically tried out various indictments of his accuser, looking for one that could get traction.

The umpire was a zealot: “He just wants to make a scene, to clean up the world…”

The umpire was singling him out: “It was a forkball. Bruce Sutter’s forkball does that too. Are you going to throw him out of a game?”

The umpire was misinformed: “He better check the rule book.”

The last accusation was weak sauce coming from an obfuscator of Perry’s talents. He was grumbling about the fact that Phillips had not inspected the ball he’d thrown to Miller. His usual catcher, Rick Sweet, took up the same complaint:

“I feel it was a setup. [Phillips] said he detected an illegal substance in the threads of the ball, but he never checked the ball.” But according to Rule 8.02a, the umpire didn’t have to do so, and Perry knew it.

The relevant passage described what would happen to pitchers that used loaded balls:

If in his judgment the umpire determines that a foreign substance has been applied to the ball, he shall: a. Call the pitch a ball and warn the pitcher; b. In the case of a second offense by the same pitcher, the pitcher shall be disqualified from the game…

This particular rule had been instituted in the wake of a 1973 season in which frustrated umpires regularly strip-searched a certain pitcher on the mound, looking in vain for the “proof” they needed to make a conviction stick. No more. Rule 8.02a—informally known as “Gaylord’s Rule”—erased the gap between suspicion and guilt.

”Now,” one official observed after the change, “all the ump has to do is pull the trigger.”

“He was warned [earlier] for having a foreign substance on the ball,” Phillips said. “I called the second one based on the flight of the ball.”

“Phillips hasn’t heard the end of this yet,” Perry said, suggesting he was considering legal action.

Hearing this, Peter Gammons of the Boston Globe observed the pitcher “would appear to have absolutely no case.” Gammons pointed out that in all this talk about improper procedure, no one was actually denying that the pitch to Miller had been loaded.

News of Perry’s apprehension made the expected headlines in America’s sports pages, but seeing the longtime offender receive a measure of justice seemed to confuse people.

Why had Perry been thrown out of a game for doing something virtually everyone knew he’d been doing for two decades? Looking at it from one perspective, a criminal had finally been brought to justice. But from another perspective, here was proof that the same criminal had been allowed to roam free for years.

“I’m surprised that any umpire would challenge him now,” said Sal Bando of the Brewers. “It’s a little late. The guy’s already won 300 games.”

So, why now?

“I don’t know why now,” Phillips said. “I wasn’t aware this was the first time for this until somebody told me after the game. I don’t keep statistics on things like this.”

The umpires had impounded two balls and these would be sent to Lee MacPhail, president of the American League, for inspection. On the morning of August 24 the league president had a 20-minute phone conversation with Perry. After that, he made up his mind.

“Gaylord Perry has been suspended for 10 days, effective immediately, and fined $250 for violation of official playing rules 3.02 and 8.02.” It had taken a decade, but the first victim of Gaylord’s Rule was Gaylord.

“He’s a [expletive] weak human,” Perry said of MacPhail. “I told him I’d played this game 20 years and I never saw anybody out to get somebody like [Phillips was] Monday night. They’ll have so many appeals that MacPhail will have to hire 10 assistants.”

Perry promised a blizzard of appeals, but really there was only one to make under the collectively bargained rules. With the help of the MLB Players’ Association Perry asked MacPhail to reconsider, automatically putting off his suspension so he could tack on a few more career wins.

At Detroit on August 29, he said the umpire, John Shulock, “checked the ball about 25 times” during his five innings (he gave up three runs and took the loss). Perry claimed Shulock told him he was “trying to find something” to support Phillips.

The pitcher also reportedly filed a petition to keep Phillips’ entire crew away from the Mariners for the remainder of the season. This maneuver doesn’t seem to have even merited a response from the umpires or the league, and the same crew worked a Perry start in Boston on September 4. The umpire behind the plate that night, Steve Palermo, checked a few balls but did not seem to be on a mission of revenge. The M’s won and Perry finally notched his 305th victory.

Perry’s appeal was heard on September 9. He was not present, reportedly tied up with “other commitments” which turned out to be a commercial taping in Seattle. Everyone else involved took it seriously. Lee MacPhail heard testimony from Phillips and Palermo, inspected two soiled baseballs, and watched game tape. A freelance court reporter took notes. A lawyer for the Players’ Association, Peter Rose, represented Perry, but we have no idea what he said in the absent pitcher’s defense.

A vexed MacPhail told the lawyer that he would hold off on a ruling for a few more days but justice was not going to be deferred forever. Perry (perhaps being advised to avoid any kind of recorded testimony) submitted a written statement a few days later. On September 18, MacPhail affirmed his earlier decision and the 10-day suspension took immediate effect.

“I was pleased that the league president seemed glad a stand had been taken,” Dave Phillips said later. “After all, baseball is difficult enough under normal conditions.”

A Mariners’ spokesperson called Perry to discuss the verdict, and he seemed resigned. “It looks like I’m going to be digging up peanuts for a while.”

Perry was, by everyone’s assessment including his own, nearing the end of his career, and the Mariners had no hope of a playoff run. Some wondered if Perry would just retire on the spot and set himself up to later insist that he never served a day of time for doctoring the baseball. But he felt there was a little more left in the proverbial tube. He served his time and returned on September 27, beating the Chicago White Sox and earning his 307th victory.

The story of Perry’s ejection resurfaced in October. He agreed to participate in the first (and only) season of a tabloid-style television show called Lie Detector. Hosted by F. Lee Bailey, a similarly tabloid-style criminal defense attorney, the show featured public figures taking polygraph tests to “settle” controversial allegations. The angle proved too icky for daytime television at the time and the show was canceled after just six installments, but it was a perfect vehicle for Gaylord Perry, whose episode made it to air.

It was harvest season at Perry’s peanut farm in Williamston, North Carolina (“Four hundred and forty thousand pounds a year. Keeps you busy.”) so the show came to him.

“They brought the whole crew here,” Perry said, “and set up their machine on the table in the den. It looked just like you see on TV police shows. They hooked me up, then everyone but two guys running the machine left so I could concentrate.”

After two dozen questions to establish baseline readings he was asked 15 questions regarding the events of August 23. Perry was quite pleased by the results.

“Passed with flying colors,” he declared. “Four practice runs and two film runs and I passed every time. I told everyone, and now they can see for themselves.”

Dave Phillips was not impressed: “Maybe that’s why the lie detector is inadmissible in court. Or maybe Gaylord has been throwing ‘his’ pitch so long that he has forgotten it’s illegal.”

One viewer noted that Perry’s polygraph session had been narrowly focused. The questions addressed only the fifth inning pitch (which caused Phillips to issue a warning). No questions about the seventh inning (when Perry was actually ejected) were asked.

It was just another farce, but Perry had mixed great pitching with performance for so long that nobody could tell the difference anymore and that was the point. In the spring of 1983 he debuted a new T-shirt in the Mariners’ clubhouse: “I’m innocent—proven by a lie detector test.”

After a final season playing for the Mariners and the Kansas City Royals, Gaylord Perry retired from baseball. But that didn’t mean he stopped working.

Despite being one of the most successful pitchers of his generation, Perry had, as the players said, “missed the money.” When he began pitching in the early 1960s he earned four-figure salaries and when free agency arrived in 1976 he was already 37 years old and looking even older. He got his biggest contract in 1981, when he made $300,000 with the Atlanta Braves. He seems to have earned about $2 million playing baseball, averaging about $100,000 per year.

He became a fixture at collector and memorabilia shows. At one show in October 1983 fans paid a $2 entry fee and a $3 fee for his signature; personal sentiments were extra. Bags of Perry-branded peanuts were available for $4. (The peanut farm would go bust in 1986.)

“Do you get paid for this?” a kid asked him as he signed a ball.

“Yep. I’ve got to make a living, too.”

Memorabilia was also for sale. On this particular day he was wearing a Royals cap. A fan asked him if he had made a strong connection to the Royals in his brief time there. He shrugged. “I had a Mariners’ hat on a while ago. Somebody bought it.”

He was always asked about the “super sinker,” but to Perry this was like asking a retired magician how he’d marked his cards. As the inquiries piled up he’d get testy. “Isn’t there anything else I did in my career that’s worth talking about?”

But what about that time in 1982, somebody would say. They got you that time, didn’t they? Can you talk about that one?

Perry smiled. He’d talk about that one. “There wasn’t anything on the ball that time,” he said.

“I took a lie detector test to prove it.”

Got any good Perry stories? We’d love to hear them!

One More Thing

He wasn’t going to spill any secrets at the convention tables, but Perry figured what people paid him to sign was their business. Once word got around that he would do it, fans often asked him to sign one item in particular:

Thank you

I just laughed and giggled while reading this. Well done, you should win a Pulitzer!

What makes baseball different than other sports is the stories. You tell them well.

Somewhat of a footnote, Perry was with the Royals when the Pine Tar Game happened, and of course Perry helped smuggle the offending bat back to the locker room, trying to hide it from the umpires (and the AL office). I'm not sure if Perry ever took back his comments about MacPhail after the Royals' protest was upheld...