Today Project 3.18 is very pleased to present what is, by our reckoning, the most inexplicable thing to ever happen during a major league baseball game.

Later, Sparky Anderson would say he thought it was a Piper Cub, though he, like everyone else, had no way of knowing for sure.

The old manager’s wild guess had some sense behind it. Thousands of the single-engine J-3 Cubs were in civilian hands in 1971. The plane was known for handling well at low speeds. That was important.

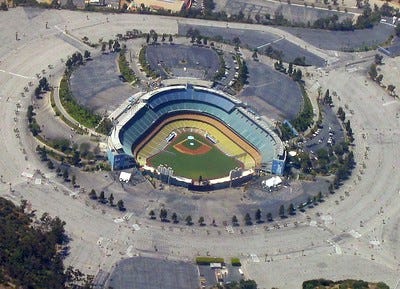

But the fact was, no one knew the make or model of the Plane because no one saw it. They were distracted and looking elsewhere as it flew overhead. Few recalled even hearing it. All anyone knew was that the Plane had come and gone, leaving an eight-foot impact radius in the infield of Dodger Stadium and two men wondering if they had just escaped an unexpected and farcical death.

They had.

But the Plane was the last plane. If we start with that story, you won’t believe us. Instead, we’ll start with the first plane, two years prior.

The first plane came to Dodger Stadium on the afternoon of July 1, 1969. This one was a Cessna 172, another ubiquitous light aircraft of the period.

It dipped low over the grandstand, buzzing the playing field somewhere between 200 and 400 feet off the ground. As a point of reference, the light towers at Dodger Stadium were 185 feet high. Federal rules required any plane above a gathering be 1,000 feet above the lowest obstacle below it, for self-evident reasons. The crowd of nearly 12,000 people didn’t know what to think. The plane whined away over the center field fence and was gone. The Dodgers beat the Philadelphia Phillies 12-4.

Until it returned, on August 7, as the Dodgers shut out the Pittsburgh Pirates. According to the unimpeachable assessment of Vin Scully, the Dodgers’ radio broadcaster, the plane looked like the same one that had visited a month earlier, and it flew, Scully said, “exactly the same pattern” that the first one had. All told, Scully thought it was the same plane, which should be good enough for all of us. This time, the 29,000 fans in attendance were ready, and one or more of them got a good look at the Cessna’s registration number—written in large, black characters on its light-colored fuselage—and took a note.

A week later, the Los Angeles Times reported that the Federal Aviation Administration had identified the craft, which was based at nearby Hawthorne Municipal Airport, and its owner.

The owner reported that he had “given the keys [to his plane] to two friends,” as well as loaning it to a flying service based out of the airport. He denied being the pilot during either incident in the skies above Dodger Stadium.

According to Ned Zartman, the FAA attorney who spoke to the Times (whose name doesn’t matter but which we are nonetheless including on its own merits), the actual pilot, if found, faced the revocation or suspension of their flying license or a fine of up to $1,000. Let us wholeheartedly hope the FAA went with the most former, if they were able to single out the culprit from a large list of friends and strangers flying this guy’s Cessna.

The skies immediately above Chavez Ravine were quiet once again…

…for less than a year.

During the 1970 baseball season, another plane appeared. We don’t know exactly when. Details on this incident are perishingly scant, but multiple accounts agree that it did happen and that it happened during that particular season. This plane flew a little higher, but as it passed overhead, at least one and possibly several “sacks full of glass bottles” were thrown away, falling perfectly onto the field below. The following year, Walter Alston, the Dodgers’ manager, recalled that the sack(s) “landed near first base. Not too far from where [Dodgers’ first base coach] Jim Gilliam was standing in the coaching box.” Why Alston had cause to recall this incident shall soon become apparent.

This wasn’t the Plane, either.

On the night of September 4, 1971, 19,000 came to see the Dodgers host the Cincinnati Reds at Dodger Stadium. The night was warm, the weather clear, affording good visibility. The Dodgers’ starter, Al Downing, was in the midst of retiring 17 Reds in a row. Sparky Anderson, the Reds’ manager, was unhappy.

In the fifth inning, the Reds’ starter, Jim McGlothlin, pitched into a little trouble and soon there were runners at first and second, with Dodgers’ shortstop Maury Wills the lead man.

McGlothlin had a good pickoff move to second, and there was a chance he would try to nail Wills if he got too adventurous. “Luckily, we had the pickoff on at the time,” said Reds’ coach Alex Grammas. This may have saved a life. The Reds’ shortstop, Woody Woodward, drifted to his left, out of the shortstop’s standard post between second and third, moving closer to second base and preparing to receive a throw from McGlothlin.

Two things happened next, so closely sequenced that there’s little consensus on which came first. We present them in no particular order.

Someone in the right field bleachers dropped a live rooster out of the stands and onto the field, drawing many thousands of eyes in that direction. Umpire Andy Olsen called time.

In the Reds’ bullpen, several players heard the drone of a single-engine, light-body aircraft. They were among the few to hear any noise overhead, and it is possible that the plane then cut its engine, gliding over the brilliantly-lit ballpark like some great, dark chicken in flight.

Then, all accounts agree, came the impact, which no one saw but everyone heard. A great, explosive thud, centered midway between second and third base, kicking off an enormous cloud of white dust.

Ten to fifteen feet away, the pickoff now forgotten, Woody Woodward looked toward the spot where he’d moments ago been standing and where he’d soon return to stand again.

Maury Wills looked at Woodward. “If that hits you, it’s all over.” Wills did not yet know what “that” was, but there was no denying the truth of his words.

There was no need to call time, the rooster had already taken care of that. Members of the grounds staff emerged to do the obvious thing, which was to retrieve and remove the animal. Doing so took three staff—roosters are no joke when agitated, which this one likely was, given the circumstances.

It was “not known,” the Cincinnati Enquirer later reported, “how anyone could sneak a live chicken into Dodger Stadium.” Also not known is what the Dodgers did with the rooster, which—wherever and however it came—had been rather spectacularly upstaged.

The grounds chief sent other men out to shortstop with rakes and brooms, to clean up whatever they found there. What they found, after some very brave soul apparently decided to taste it, was baking flour, approximately ten pounds of it, distributed across a wide radius of impact, along with the remains of a tightly bound paper bag.

Only later did anyone discover the second flour package, detonated in one of the parking lots beyond the right field pavilion, further back along the path the Plane took to fly over the field. This may have been a range-finder.

It took approximately ten minutes to catch the bird and clear the field. Vin Scully, baffled and alarmed by the plane and the flour, stuck to making light of the rooster.

When play resumed, Woodward gingerly made his way back out to his normal position, keeping, he said, “a wary eye on the heavens.” The batter, center fielder Willie Davis, hit into a double-play. Woodward, the pivot man, got a putout and an assist.

“There’s not too many things I haven’t seen now,” Woodward said after the game. “I’ll tell you this—I don’t drink much beer but I’m gonna have me a couple tonight.”

Woodward then added a tantalizing detail to the Bottle Bag Incident from 1970. Following his own near-miss, he said that someone told him that this was kind of a “thing” at Dodger Stadium of late: “[I heard that] last year a guy dropped a bag of bottles out of an airplane here and he was caught.” Was he, though? If he was, it got kept really quiet.

After the game, Ted Kluszewski, the Reds’ hitting coach, showed a knack for improv by fashioning a pretty solid joke from the disparate nouns and verbs that the game had brought together. “That was Chicken Little out there in right field and he was trying to tell everyone the sky was falling,” he said, laughing. And then he seemed to reflect a little more: “If anyone had been hit by it, they’d have been killed for sure.”

Jim McGlothlin did not have a joke. “When that thing hit it sounded like a mortar shell going off. It was an eerie feeling, like being in war. The rest of the game you were waiting for another one to hit you but you couldn’t hear that coming like you can hear a mortar shell.”

“They ought to get that guy for attempted murder.”

The national sports pages were not used to investigating aerial bombardments, a blind spot that showed in their coverage of what had happened.

A 50-word blurb from the Associated Press, inexplicably titled “Flying Flour Sack Aid to LA1,” was particularly frustrating (emphasis ours):

“The flour sack apparently was dropped from an airplane, or was catapulted from beyond the outfield fence.”

Really. A catapult. Did no one check the acres of parking lots and the rest of Chavez Ravine for catapults over the course of the next four innings? One imagines that a medieval siege weapon in the area would have been hard to miss.

Furthermore, the players’ accounts suggest the flour fell straight down from overhead. We are not sure it is even physically possible to make a catapult that produces an arc so large that by the end the projectile is coming straight down at a ninety degree angle, but we’ll leave that to the physicists and engineers.

If you are a physicist or engineer:

The other press syndicate at the time, United Press International, made a wholly unsatisfying report that a white, powdery substance “floated down on portions of Dodger Stadium, holding up play briefly.” Facts, we suppose, but not truth.

The Cincinnati Post reported that “radar showed a number of planes in the vicinity of Dodger Stadium,” suggesting (with quite unnecessary use of quote marks) that this made it “unlikely that the ‘bomber’ would be apprehended.” Did the Post beat writer happen to have a radar station running out in the parking lot during the incident?

The Dodgers do seem to have reported what happened to the Federal Aviation Administration, but another account said that the Dodgers’ organization itself was “investigating several low-flying planes” in the area, without bothering to explain how exactly the Los Angeles Dodgers franchise had the capacity to investigate rogue craft in their airspace. These days, such an assertion would make perfect sense, but this was 1971.

Within a day or two, the story was subsumed by the regular accumulation of other, more easily-digested sports news. Neither the Plane nor its pilot were ever (publicly) identified.

And though the whole thing quickly left public awareness, those who’d been there did not forget. In 1980, Sparky Anderson was managing the Detroit Tigers, who were experiencing some difficulties with their bleacher fans2. Sure, there were some beach balls falling in the outfield at Tiger Stadium, but the manager described the strangest thing he’d ever seen happen during a baseball game.

“Woody Woodward was playing shortstop, and Maury Wills was the runner on second base,” Anderson recalled.

“All of a sudden there’s a big explosion of white between them and this big white cloud goes up maybe 10 or 12 feet from Woody. My God, this cloud went up in the air like a bomb. Some guy in a Piper Cub had cut his engine and glided over the field and dropped a 10-pound sack of flour right on the field. Can you imagine if it had hit one of those guys on top of the head? It would have driven him right down in the ground like a fencepost!”

Most of the time, in a story set in a baseball game, we will be sure to state, even briefly, what happened in the game, whether or not that matters to the story. We do that because saying what happened in the game is the Baseball Story equivalent of the Lord’s Prayer, offering a way to center oneself in disorienting and challenging experiences, e.g.: “Anyway, the Tigers won (amen).”

But we’re not going to do that here.

Quite the opposite: We believe that all details3 from the Reds-Dodgers game of Saturday, September 4, 1971 should be subsumed in the historical record by the more noteworthy cultural event the game produced. Henceforth, we should speak of “The Plane!” the same way we refer to other proper-noun events that happened to occur during a baseball game: the Earthquake, the Bird, and so on. Does it matter what else happened in a game where Randy Johnson accidentally vaporized a most-unlucky dove with his fastball? No. Does it matter what else happened in the game where a shortstop was nearly killed by a plane-borne, gluten-based munition?

It does not.

On September 17, 1971, just thirteen days later, the Weirton Daily Times covered a strange local event. Weirton, we should tell you, is in West Virginia, near the very tip of the spike at the top of the state, with a population around 27,000 at the time.

“Wintersville High School Bombed With Flour,” the article announced.

Earlier that week, a single-engine plane was spotted circling the high school and its football stadium at an unusually low altitude. The students were indoors during the incident, but several custodial workers and Robert Kettlewell, the football coach, noticed the craft and followed its progress. Kettlewell said the plane buzzed the school twice before flying off briefly and returning, and on the final pass it flew so low it barely cleared the stadium lights.

According to the eyewitnesses, the plane was cream-colored with a second accent color they couldn’t make out. None of them knew the make or model. After it flew off for good, staff found “two paper bags of flour outside the school,” apparently dropped from the aircraft. The school said they reported what happened to the police, but there were no follow-up reports.

This last incident begs a question.

Rather than landing at a nearby airport, had the Plane flown on from Dodger Stadium and across the country until it ultimately reached its second target: Wintersville High School in Weirton, West Virginia?

Don’t be ridiculous, you say?

…

You know, you're right. It would be our mistake to tarnish this story by adding anything ridiculous.

Thank you for reading (and liking and sharing, etc.) this true Baseball Story from Project 3.18. If by some miracle you are (or know) an elder Dodger fan who remembers being present at the strangest game of the 1971 season, please reach out to us at project318@substack.com and share those memories.

And if you remember being at a different game that featured strange surprises or Proper Noun-level events, leave a comment. We’ll be sure to pass any relevant information on to the FAA.

We’re having a blockbuster week here, so we’ll be back tomorrow, bringing you the story of a fashion fad that took over baseball—and everywhere else—coincidentally (we think) in very same year that the Plane flew over Chavez Ravine.

Tomorrow: “Good Legs and Guts”

How would almost killing Maury Wills, second-closest to the point of impact, aid the Dodgers?

Stay tuned for more on this in a future piece.

With one exception. We must all remember Woody Woodward’s subsequent assist and putout. Under the circumstances, that was a heroic play.

The rooster first, then the flour bomb, what an insane one-two punch.

There was a nice write-up of this event in the Athletic in 2020 I think, they didn't have all my background stuff but they did, in the way of journalists, have some nice quotes from people like Woody Woodward in present-day. But even more interesting was the lengthy comment posted by someone claiming to have been the person who got the rooster into the park, having been sent the article by a friend. He was sketchy on his methodology, so I couldn't give it the Project 3.18 seal of authenticity, but if was really him, he claimed to have let the rooster out just before the bomb fell. He had told some other friends coming to the game that night to "expect a surprise," or something vague like that, and, having not even noticed the rooster, they looked at him with a combination of fear and awe when they saw him later.