A Haunted Player - Part 1 of 2

What "unnatural" power got a talented catcher banished from every league in 19th century America?

This is Project 3.18, a newsletter where we remember moments when baseball didn’t go as planned, tell stories with fans, and write about history and culture through the lens of the National Game.

If you enjoy this article, you can use the provided button to subscribe and receive future stories for free in your inbox. And don’t miss the archives, full of forfeits, ejections, and wild tales from every era of baseball.

Recently, we got a request from a very important reader: our mom. She wanted a Halloween story…from Project 3.18. A baseball nonfiction Halloween story? Is that a thing?

To make it a little easier on ourselves, we approached Halloween as more a state of mind than a date in late October. Even then, this was a tough order to fill.

The breakthrough came as we were digging into the evolution of baseball superstitions for another project. We expected ladders, backwards caps, broken bats, etc., and we certainly found that stuff. But—at the bottom of a 1906 list of ill-omens and jinxes—we were surprised to encounter an actual person:

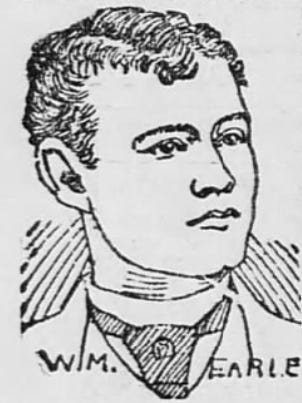

There was one ball player who was driven out of the business and almost to death by superstition. That man was little Billy Earle.

Order up!

The first mystery of William Moffat Earle’s life is why everybody called him “little.” Billy Earle was not little; he was five-foot-ten. In his time—the late 1800s and early 1900s—the average height for men in America was five-foot-seven, making Earle comfortably above-average, but we suppose “above-average Billy Earle” doesn’t have quite the same rhetorical snap.

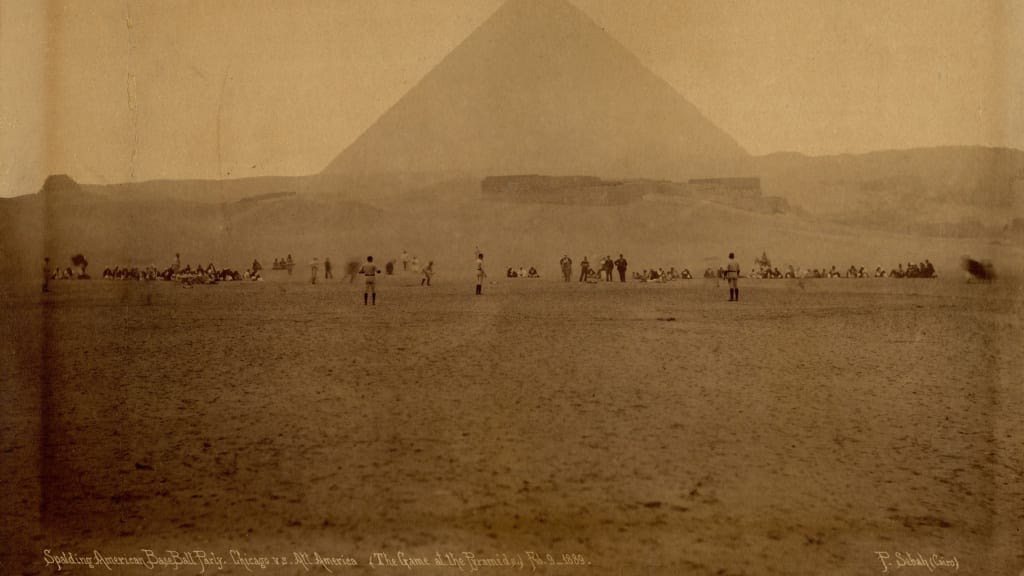

The other go-to honorific for Earle was “globetrotter,” and that one definitely fit. In parts of 1888 and 1889, Earle participated in A.G. Spalding’s baseball world tour. The tour took two teams—Spalding’s Chicago White Stockings and an All-American team of “all-stars” from the other clubs—to play exhibition games all over the world. The goal was to create thousands of new baseball fans on every continent but Antarctica (all of whom would buy their equipment from Spalding, who owned a sporting goods company) and demonstrate America’s capabilities as a cultural exporter.

Uniquely among the “Tourists,” Earle hadn’t played a single game in a major league, but he was signed to begin playing for Cincinnati and he wore their uniform on the trip, catching for the All-Americans. He and the other players who participated weren’t paid much, but they received enduring fame and an extraordinary travel experience for people of their backgrounds:

We played everywhere from the catacombs of Rome to Cheops in Egypt, in the shadow of the Pyramids, and out through India and the island of Ceylon (Sri Lanka). I remember one game in Ceylon where 17 nationalities witnessed the contest. In Egypt we were playing on a diamond over 6,000 years old. It wasn’t “Hit it to the fence,” but “Hit it to the sphinx” in that series.

Traveling the world on Spalding’s tour was an enduring badge of honor, but back at home, the goal was to stay in one place, playing for one team. By that standard, Billy Earle was a truly remarkable failure.

Here is a back-of-the-envelope list of the clubs Earle played for and/or managed between 1884 and 1897. We’ll bold the major league teams, for whom he played a combined total of just 152 games.

Nashville Memphis Duluth St. Paul Cincinnati St. Louis Tacoma, Sioux City Pittsburgh Seattle Birmingham Pittsburgh (again) Louisville Brooklyn Minneapolis Dallas

Throughout his career, Earle seems to have played only catcher. How good a player he really was is hard to say. Reports of his throwing arm varied, but he was often lauded for his offense. In the majors, sometimes he hit .230 and sometimes he hit .350, but the number of at-bats was always tiny. Earle was forever sliding off the last seat on the bench, signed as a third catcher and then quickly released or sold for reasons unclear, or at least undisclosed. “It didn’t work out,” was the gist of Earle’s entire major-league career.

“It is a peculiar fact,” one newspaper observed in 1895, “that sober, steady Earle is never held long by any league club, no matter how well he plays, and he is feeling discouraged.”

But he’d always pop up somewhere else, often halfway across the country. In some of his minor league seasons, with more playing time, he’d hit over .400. He may have been what we today think of as a “AAAA” player: someone too good for the minors but not good enough to stick in the majors, stuck in baseball purgatory.

The Cincinnati Enquirer kept close tabs on Earle, who played for the major-league Cincinnati Red Stockings in 1889 and made the city his offseason home. According to the Enquirer, Earle’s nomadic difficulties had nothing to do with his on-field work. The problem was that the other players couldn’t stand to be around him. Billy Earle, the paper explained, was a living, breathing “hoodoo.”

The term hoodoo has roots in African spiritual practices (perhaps related to the term voodoo, but perhaps not) and was brought into the American vernacular by some of the millions of Africans who were kidnapped, enslaved, and transported to the United States via the Atlantic slave trade. The term has a complex and nuanced history, but given our purposes here, we’ll use the definition from Paul Dickson’s excellent Baseball Dictionary:

[A hoodoo is] an object, sign, player, or anything else about which a player, coach, or manager is superstitious; An object, animal, or person used to bring bad luck.

So how did Billy Earle become the human version of a broken mirror? The Enquirer explained:

Earle, wonders why he is released, but nobody else does. It is not his ball-playing that [makes him strange]. It is his talk about his powers. His companions on the ball field do not like it.

According to the paper, Billy Earle was a practitioner of hypnotism, able to overrule people’s conscious minds and make them do his bidding. And this was not just a rumor—the catcher admitted it. He even humble-bragged about it, to another Cincinnati paper, the Times-Star:

I cannot describe how I am able to control these subjects, but I have failed just seven times in experimenting with 115 people. Of course, the conditions were not as hard as those encountered by the mesmerists whose subjects are placed before a large audience.

Hypnotism was a subject of uneasy fascination in Victorian society, considered either a taboo, semi-supernatural art or an emerging pseudoscience, depending on who you asked. The practice had the kind of mixed reputation a Ouija board1 has today. Some saw it as harmless fun, while others saw it as a reckless and potentially dangerous embrace of unnatural and unexplainable forces.

We found the first public account of Earle’s connection to hypnotism in 1890. At that time, he was in Tacoma, Washington, playing for their minor-league club in the Pacific Northwestern League.

That season, the Times-Star reported that “Earle’s mind runs largely to mesmerism,” and provided testimony from a former teammate, Jerry Harrington, who witnessed “some experiments on a hypnotized subject (a young woman) which made his eyes search for the door and a mode of escape.”

“Blessed if I didn’t get scared,” said Harrington. “[Earle] stuck her arms full of needles and ran a hairpin through her tongue, but the girl never moved. When he brought her around, I asked her: ‘Didn’t he hurt you, putting all those pins in you?’ ‘Why, he didn’t do a thing like that, did he?’ she replied.

These early2 reports were often tonally neutral and sometimes even approving. According to The Sporting News, Earle could have a promising second career as an stage hypnotist.

Should circumstances compel his retirement from the baseball profession, Billy Earle need never lack for a means of livelihood… The little catcher is a mesmerist of no mean ability. This season he has furnished pleasure and amusement to his comrades, and he has helped them to while away many an hour.

According to the paper, “under Billy’s instructions,” one player broke into song. Another player “was forced to succumb to [Earle’s] will and make a ‘monkey’ of himself,” without saying what this entailed. Perhaps Earle literally made him act like a monkey.

The Sporting News article on Earle was a baseball-centric take on hypnotism’s amusing and/or disconcerting power to disrupt a particularly uptight society, as shown in the illustration below from the same general period:

Hypnotism could be amusing, but many Victorians distrusted anything they couldn’t fully explain via science or the Bible. In 1845, Edgar Allen Poe wrote a short story about the sinister, ghoulish power of hypnotism that many readers mistakenly took as nonfiction. Bram Stoker’s last novel wasn’t a sequel to Dracula, but instead featured a villainous, predatory mesmerist.

Even The Sporting News could not resist a comment on the possible risks of hypnotic suggestion in baseball, delivered via a joke about bad umpiring:

Possibly this unnatural power of Billy’s [explains] the strange actions of the umpires in the recent Seattle-Tacoma series of games, as their duties kept them in the Earle’s immediate vicinity.

More and more of Earle’s teammates began to worry about playing with a hypnotist. In his unusually-piercing eyes, some of his teammates feared “the evil eye” that could be weaponized against them in Earle’s quest for victory, or at least more playing-time. Some opposing players were known to walk backwards to the batter’s box to ensure they did not make eye contact with Earle during a game, lest they be hexed.

By 1894, strange stories of Billy Earle had spread from player to player, from Cincinnati to Tacoma, Tacoma to Pittsburgh. The emerging consensus was that Earle was too close to the supernatural for anyone’s comfort; that he was cursed by bad luck as a result of his dabbling in the unexplained. And—worst of all—whatever he had might be contagious.

Earle would later recount his struggles during that particularly nomadic year:

I began as a manager of the Birmingham team, but the Southern League blew up on July 4th. I was then signed by Pittsburgh and was then loaned to help out Louisville.

Just for a joke one day on the train, I hypnotized a woman. The players saw me and began to freeze me out. My roommate refused to have anything to do with me. [Teammate] Jack Grim hadn’t hit even a foul for three weeks and yet he declared that I had hoodooed him.

One of our pitchers lost his arm. They said I was the hoodoo. I was sent back to Pittsburgh. Up to that time the Pirates had been playing great ball, but when I rejoined they went to pieces and played miserably.

My manager declared the hoodoo and fired me–although I was playing the best [baseball] of my career.

Jake Stenzel also played for Pittsburgh in 1894. “We [players] were not afraid of [Earle],” he said in 1899, “but it used to be mighty unpleasant to have him stealthily following us about trying to use his ‘power,’ as he called it.”

Stenzel appears to have been one of the players who witnessed Earle’s “joke” on the train.

The team was coming from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh during the World’s Fair, and the trains were crowded. Earle was in the seat with a girl about 16. The first thing we knew, the girl and Earle were almost facing each other and she was answering all kinds of questions.

The players didn’t understand what happened next, only that something had gone wrong.

Earle became frightened and began running his hands through his hair and snapping his fingers to bring her out of it, but it was useless, and in an instant Earle had turned and lunged through the open window. This seemed to break the spell and the girl recovered and said she had had such a funny dream.

There were also stories of strange behaviors in the dark. In one such account, Earle’s assigned roommate woke up in the middle of the night to find the catcher sitting up in bed and shouting: “Knowledge is what we want!” Despite his open eyes and clear voice, Earle was not responsive. His frightened roommate eventually grabbed a bat for protection and yelled: “This is what you’ll get if you don’t cut that business out!”

During a very brief stint with Brooklyn in 1894, only one player would share a room with Earle. Tom Burns told the catcher he was aware of his reputation, but didn’t believe in hoodoos. Burns and Earle shared a berth on an overnight boat trip between New York and Boston. As Earle told it, while climbing into his top bunk bed late one night, he accidentally touched Burns’ arm with his foot.

“He jumped out of his berth with a roar,” Earle said, “opened the door, ran through the cabin to [the owner’s] stateroom, and woke up the whole boat. He told Mr. Byrnes that I was trying to hoodoo him.”

Other accounts suggested perhaps Earle was deliberately trying to pull a prank on Burns. We don’t have Burns’ account, but the fact that he refused to return to the room and spent the rest of the night on the ship’s open deck speaks for itself.

The next morning, Byrnes, the Brooklyn club president, pulled Earle aside.

He told me confidentially that the players were all afraid of me, though he didn’t really believe there was anything in Burns’ accusation. I had to leave the team. All the rest of the year I was boycotted by ballplayers and couldn’t get a job.

Because of Earle’s Tourist pedigree and pleasant demeanor, many press outlets were sympathetic to him. One editorial used 500 words to say that Earle’s problems were caused by baseball players being the dumbest and most backward segment of American society, worse, even, than actors.

It seems almost inconceivable that in this land of free popular education there should exist, outside of the lunatic asylums, any large body of adult males ignorant and superstitious enough to dread what they call “hoodoos.”

By October of 1897, Earle claimed he had gotten out of hypnotism years earlier, presumably circa 1894, when he’d received national attention for being a kind of baseball bogeyman. Now his baseball career seemed to be circling the drain. He was reported to have “a chicken farm somewhere out near Richmond, Virginia,” but was still trying to get back into baseball, with increasing desperation.

In 1897, many teams needed catching help, and Earle said he was ready to work for free until he’d proved his worth. That autumn he left the chicken farm and made his way to Baltimore, where he was a guest of the National League Baltimore Orioles.

If you are a regular Project 3.18 reader, believe it or not, you actually know a couple of guys on this 19th century team. Their best player was their irrepressible 28-year-old shortstop—and hit-by-pitch specialist—Hughie Jennings. And their third baseman was the pioneer of hard-nosed, bang-up baseball, John McGraw, just 24 and already regarded as as much of an on-field terror as Earle was off of it.

Billy Earle had somehow maintained a friendly relationship with the rough-and-tumble Orioles. Even though they didn’t need a catcher, the first-place club invited Earle to hang around and meet up with any teams passing through Baltimore who might want to sign him. He was in town between August 31 and September 3, hoping to try and catch on with the St. Louis club, but nothing panned out.

Around the time that Earle visited, the Orioles entered a 14-game winning streak and claimed a narrow lead over Boston in the standings. But in mid-September, the Orioles scuffled, finishing the season 5-6 and losing the title to Boston as a result. Even though he had not so much as appeared on their roster that season, some of the Baltimore players traced their demise straight back to Billy Earle.

The story came in the Louisville Courier-Journal, who had it from Tim Hurst, an umpire.

In a recent game that Hurst officiated, the Orioles’ catcher, Wilbert Robinson, made several errors that cost three runs, resulting in a crucial loss. After the blown plays, Hurst said he heard Robinson “holding conversation with himself,” saying strange things like, ‘I’m a miff, I’m a Jonah3, I knew these shoes would turn the trick.’”

Hurst: Robbie, says I, what do you mean by shoes turning the trick?

Robinson: Billy Earle came to town last week and he was broke. He touched me for $5 and I asked him what he could give me for [collateral]. He produced a pair of baseball shoes and they fitted me like an old slipper. I gave Billy the $5 and took the shoes. This is the first day I have worn them, and I’ve been catching a bum game. Earle has Jonahed me. I always said he was a Jonah, ever since I heard he put guys to sleep with that hypnotism racket he springs.

After the game, Hurst said he’d heard the Baltimore players talking and agreeing that Earle’s cursed shoes had put them out of the race.

The umpire himself was not superstitious. The moral of the story, he said, was that all of these grown men were evidently idiots.

A month later, Billy Earle wrote to the owner of a startup semi-professional team in Butte, Montana, one among 31 applicants for a volunteer club (the owner promised to help with local job placement). Earle promised he would change his name in order to keep anonymous and avoid disrupting the other players. His bad luck continued; not only was he passed over, someone shared his application letter with the local newspaper so they could report on his strange circumstances and accelerating fall from grace with ghoulish frankness:

Earle is known as a haunted player. … He says he would rather be dead than not play ball, but he can’t get a chance to play anywhere.

In other words, watch this space.

Of course, if past was prologue, the public would surely not have long to wait to learn where the strange but doughty Earle would turn up next. He always did.

Except this time he didn’t. At the end of 1897—despite living in the Victorian equivalent of a media bubble—little Billy Earle suddenly vanished.

Here’s an embed to the conclusion!

On October 28: A Fiend in Need

Yes, we are in the latter camp. Hard nope with extra nuh-uh.

Doing our final read-through and just noticed this accidental pun. Keeping it.

”Jonah” was another popular expression for a person cursed with perpetual bad luck, a reference to the biblical figure of the same name, who famously spent 72 hours inside a whale, or at least a large fish.

That was a delightful historical account, Paul, and I can’t wait until next week. I promise I won’t go to Google or Wikipedia in the interim. I found it funny that the reputation of a “hoodoo” was “even worse than actors.” And we all know that in prior centuries, that actors were of ill repute. Meg

I came here to say that

Thanks Melissa.