Hughie's Tin Whistle

In 1907, a rookie manager makes some real noise in the young American League.

Last week we looked at some sensory-adjacent ejections, and our pick for “Sound” was easy. In late July, 1907, Hughie Jennings, the manager of the Detroit Tigers, was ejected twice in three days for the same offense: “Blowing [a] whistle.” And while most of our ejection tales begin and end in a single day, wiped away with the turn of the calendar, this story went delightfully onwards, becoming a pop-culture moment and shoving its way into baseball’s stodgy halls of power and even the World Series.

On July 25, 1907, Hughie Jennings was ejected from Detroit’s game against the Boston Red Sox. The matter of dispute is not clear in the immediate coverage, nor was Jennings’ offense, but the manager was reportedly “meek enough when he was sent to the bench from the coaching lines” by the series’ lead umpire, Silk O’Loughlin. The incident would have gotten no more attention than that, except for what happened two days later.

Jennings was a first-year manager in 1907, brought in to revive a flailing Tigers club on the strength of his 18-year career as a player, notably as a member of the revolutionary Baltimore Orioles teams of the late 1890s, where he played alongside John McGraw, Wee Willie Keeler, and Joe Kelley (collectively the Four Horsemen of Scrappiness). Jennings was the Orioles’ shortstop and specialized in managing to get hit by pitches to earn free bases, setting up the running game. He and his teammates were renowned for coming up with shrewd and ruthless ways to gain an edge in what was supposed to be a genteel sporting contest. As a manager, he was now trying to bring this same sense of urgency to the Tigers.

On July 27, Jennings was ejected again, but this time, there were more details. The manager’s offense was noted—indeed, it could not be missed by anyone in the park that day. He was ordered off the field “for using a whistle on the coaching lines, after having been warned by the umpire it was against the rules.”

Now, you know what our next question was: “What kind of whistle was it, exactly??”

And we have answers, if not an answer, because descriptions of the instrument varied. It was referred to as a “tin whistle,” a “silver whistle,” a “small, harmless whistle,” and, intriguingly, a “postman’s whistle.”

The tin whistle, also called a penny whistle, is basically a very simple and very cheap six-holed recorder. It’s meant for playing simple melodies, and it has a gentle, rather inoffensive sound.

The postman’s whistle, on the other hand, is an ear-splitter. There was nothing mellifluous about these nickel-plated brass monstrosities. Compact and one-note, their function was to make noise. The name derives from the fact that postal workers in turn-of-the-century England and the United States carried such whistles, which they would blow when arriving in small communities so people could come and meet them for services (buying stamps, that sort of thing), and also after dropping off mail in rural areas where the mailbox might be a long ways from the house. When blown forcefully, these little shriekers could carry over 900 yards.

Here’s a clip of such a whistle being blown, and it’s helpful to have that shrill blast in your mind as this story continues.

During that July 27 game against the Red Sox, O’Loughlin endured a few piercing shrieks before sending Jennings back to the bench, but did not immediately remove him from the game. This was a mistake, as the manager whistled again from the dugout. Now O’Loughlin “fired him off the bench and sent him to the dressing room,” but Jennings instead embarked on a little tour of Boston’s Huntington Avenue Grounds, “wending his way to the shail1 between the stands near his own bench, giving vent to his war cries and blowing to his heart’s content.” The Tigers, sufficiently inspired, won 5-4.

This time, Jennings appears to have been suspended, but it’s not clear when or for how long. In any case, he was definitely back on the sidelines by August 2, when Detroit continued their road trip against the Washington Nationals at American League Park. As was his whistle.

Per the Washington Herald:

The most amusing and entertaining feature of the three games … was the unique and original coaching of Hughey Jennings. The outlandish language used by Jennings in encouraging and directing his men from the coaching lines kept the crowds in good humor, but the biggest hit was when the manager pulled out a little tin whistle and blew it to his heart’s content.

This time, nobody threw him out, the Tigers won four out of five games in the series, and—for the first time all season—moved into first place in the American League. There could be no doubt: Hughie Jennings had found a good luck charm.

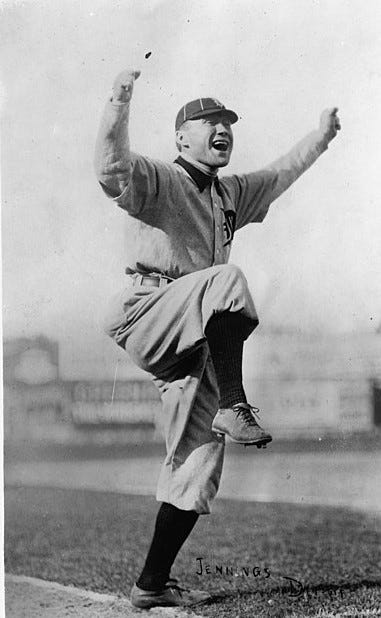

As a manager, Jennings quickly distinguished himself through sheer exuberance. Building on habits he developed as a player, he would stand in the coaching boxes next to first and third and keep up a constant stream of verbal patter, a good portion of it unintelligible nonsense, sprinkled with the occasional baseball word that, if you knew what to listen for, gave a coded signal.

He had developed a habit of celebrating his players’ arrival on base with delighted shouts, throwing his limbs in the air and shouting “Ee-yah!” or “Attaboy!” (the latter expression may be more familiar to modern readers—Jennings claimed credit for inventing it).

When he wasn’t jumping or marching, he was restlessly plucking grass out of the coaches box and generally endeavoring to be a distraction. The persona seemed to be working; the Tigers had finished in last place the year before, but throughout 1907 they had steadily risen in the standings.

But all that yelling and whooping had come at a cost: at the opening of the July series with the Red Sox, Jennings had reportedly come down with “a throat affliction.” Requiring an alternative instrument, he procured a whistle, from which he “let loose a shrill blast” each time a Detroit player got on base. This is what had gotten him ejected on July 25, the game from which he went “meekly,” but after being removed he’d decided he’d done nothing wrong, and resolved to bring his whistle back again, on July 27, the day on which he made his roving performance and ultimately received a suspension.

The suspension would have come from the president of the American League, Ban Johnson (who we last saw in 1918, instituting march and drill training in a futile effort to keep baseball players out of World War I). In 1907, the American League was just six years old and Johnson was its powerful father figure. The president had reportedly “set down his foot, and 300 pounds of superstructure, on the use of a whistle or any other ‘mechanical device’ for coaching purposes.” He was quoted as saying, “whistles will do for postmen and policemen but they won’t go in the American League.”

The dispute made national news, for the same reasons we’re covering it here: the whole thing was absurd. Nonetheless, the Herald reported, “while they may appear ludicrous, Johnson and his umpires are as serious over the situation as a set of old owls.”

But so was Jennings. The manager might be new to his trade, but he was not new to the rules—he knew them cover to cover, and there was nothing in them about whistles. Jennings happened to be a stickler for the rules—he was a practicing lawyer.

While a player for Brooklyn, Jennings had decided to study the law as a means to an offseason vocation and enrolled in Cornell’s law school. Despite having only a high-school education and missing the last year or so of classes, he passed the bar exam in New York and maintained an active law practice for the rest of his life.

He vowed to fight the whistle ban by taking the matter up with the full National Commission, baseball’s governing body, at its next meeting. Until then, the whistle seems to have made several follow-up appearances. At one of the Washington games, a fan presented Jennings with a toy trumpet, but this risked pushing it, even for a professional button-pusher. “He stuck to his little whistle, which he blew with great joy every time the Tigers scored, which was not seldom.”

By September it was clear that the Tigers were the real deal and Jennings had moved into managerial heads across the league, rent-free.

His antics were making the game unserious, some of his peers warned, including Clark Griffith of the Nationals, who wrote Ban Johnson to threaten escalation: “If Jennings can use his whistle,” Griffith warned, “we’ll use megaphones and base drums.”

Trying to make a point or steal some publicity during a home game against New York, Monte Cross, a player and part-time coach for the Philadelphia Athletics, showed how escalation would look in practice. Cross reported to the third base coaching box carrying a squeeze horn of the kind that were mounted on period automobiles. The umpire on duty, Tim Hurst2, did not appreciate this stunt at all:

As soon as he could get over his astonishment, [Hurst] rushed at Monte and tore the horn out of his hands, throwing it over a fence.

“Ye fule,” yelled Hurst, “what thee divil are ye tryin’ to do with the great national pastime, make a comic op-ry out of it? Hey! Get out of here!”

(Just to be clear, we’re not doing voices—that’s the verbatim quote from the published report.)

Cross was apparently loaded for bear, with “a whirl-a-gig, a tin pan, and other instruments of torture to amuse himself with.” It was all part of a plan to try and stymy Jennings’ growing popularity, even among fans in rival AL ballparks.

As Hughie Jennings’ sideline whistling boosted his Detroit Tigers to an unlikely pennant, the manager’s antics entered into broader cultural awareness. For example, a Pennsylvania vaudeville performer made headlines in September with his Jennings-focused rendition of a popular ballad: “When You Know You’re Not Forgotten By the Girl You Can’t Forget.” (A big hit in 1906; careful, it’s catchy)

And he’ll know he’s not forgotten By the fans who can’t forget That he’s reaching for the pennant, And he swears he’ll land it yet. If old Ban won’t let him whistle, We’ll whistle for him, you bet; And he’ll know he’s not forgotten By the fans who can’t forget.

By September, the Tigers were locked in a battle for the pennant, pitted against the closely-trailing Athletics. Detroit’s secret weapon was its 20-year-old center fielder, playing full time for the first time after two part-time seasons while still a teenager. Ty Cobb was tearing a hole in the circuit, on his way to collecting 212 hits, 119 RBIs, and 53 stolen bases, leading the league in each category. His .350 average was similarly good enough for a batting title, but future seasons would show that early number to be rather modest for Cobb.

Jennings, for his part, had quickly realized that Cobb was probably the best player the sport had yet produced, and he let him play his game without much interference. As he once told Cobb, there was nothing he could teach the younger man, who had seemed to arrive fully-formed as a perfect engine of the game.

Cobb and his teammates locked up their first ever pennant with a four-game sweep of Washington in early October, setting them up to face the repeating National League champion Chicago Cubs in the fourth iteration of the World’s Series between the two league champions. The Cubs, having won 107 games, were clear favorites, featuring stars around the diamond (Joe Tinker, Johnny Evers, player-manager Frank Chance) and on the mound (Mordecai “Three-Finger” Brown).

The Tigers had momentum going into the World Series. Detroit had finished their season with a 15-game road trip and won 11 times. Two of their losses happened on the last day of the season when the pennant was already decided, and once they tied in an epic, 17-inning clash with the rival Athletics. Between September 24 and October 5, they did not lose .

Before the Series began, representatives from both teams would appear before baseball’s National Commission, the three-person governing body that managed the bicameral sport, composed of both league presidents and August Herrmann, the owner of the Cincinnati Reds and chairman of the panel. The two umpires who would work the series would also attend: Hank O’Day representing the National League and Jack Sheridan representing the American League.

The pre-Series meeting was held in Chicago before the start of three games at the Cubs’ West Side Grounds. The event was part business meeting and part media day, open to reporters who could cover the ceremony and interview the participants to hype the series.

At 5:00 pm on October 7, Jennings and Chicago’s Frank Chance presented themselves at the Auditorium Annex building. Chance reportedly showed the “nervous strain” of a manager whose favored team had blown it in this same spot the previous year (against the rival White Sox, no less), while Jennings was reported to be all smiles and confidence, an “auburn hair electric battery, as happy as the kid with the proverbial red top boots.”

Once business got underway, Chairman Herrmann did most of the talking for the commission, while American League president Johnson was reported to have slept through most of the proceedings.

Hermann congratulated the teams and urged them to observe the rules, saying the umpires had been instructed to “observe the strictest discipline” and that he hoped there would be no occasion for them to put any player out of the games.

After hashing out a few profit-sharing matters, the day’s old business was concluded, and Jennings raised his hand.

“Mr. Chairman,” he said, rising to his feet. “Will there be any objection to the use of an inoffensive little tin whistle in the world’s championship series?”

“As far as I am concerned, I have no objection to the use of the famous little noise maker,” said Herrmann. Jennings seemed to have triumphed, but then Herrmann showed his colors as a true bureaucrat.

“You understand that I said ‘personally,’ Mr. Jennings, as the use of the whistle on the field will be in the hands of the umpires.” The chairman clearly did not want to be recorded as the bad guy, leaving the officials to take the fall, which they gladly did.

“The coaching rules will be strictly enforced,” said O’Day. “And there will be no tin whistles used.”

He ended up being half-right.

Without the whistle’s supernatural powers, the Tigers plummeted back to earth. They managed a 3-3 tie in their first game against Chicago, but a 3-1 loss in Game Two seemed to suggest the 107-win Cubs were correctly identified as favorites.

Jennings, to his credit, largely honored the sport’s decision to keep his whistle out of the series, but by then his throat was recovered and he made typically good use of it.

He was initially scolded by Hank O’Day for making too much noise on the lines and for clapping hands when there was no one on the bases, but Jennings won the argument that noise made by “natural” means was not limited under the rules. “Jennings has forgotten none of his antics,” an admirer wrote.

In Game Two, he even made history by arguing a caught-stealing decision at second base to the extent that O’Day sent him to the bench. It was the first-ever ejection from a World Series game.

Jennings was reportedly a long way from being discouraged or uneasy after the Tigers’ first loss. “Sir,” he told a reporter, “we have not yet begun to fight.” A nearby Chicago loyalist had a quick response: “He’d better begin pretty soon.”

Jennings maintained his spirited coaching “and the grass around his box suffered accordingly,” but the air was steadily let out of his Tigers. The Cubs won both decisions at the West Side Grounds in front of huge crowds, and the Tigers returned home down two games to none.

Against the Cubs’ two best pitchers, Three-Finger Brown and Orval Overall, Detroit managed just one run at their home park, in front of increasingly-smaller crowds. The Cubs ended the World Series with a 2-0 shutout on Friday, October 12.

It was a disappointing ending, but the Tigers and their manager had much to be proud of. “Jennings took a tail-end team and moved it to the top of the ruck.”

Detroit appeared in back-to-back-to-back World Series between 1907 and 1909, but they could never quite make the summit, losing twice to the Cubs and then to the Pirates. They were missing something. It was as if, in 2002, commissioner Bud Selig banned the Rally Monkey from appearing for the Angels. Or what would have happened here in 2024 if commissioner Rob Manfred declared the Grimace to be persona non grata at Citi Field in New York. In baseball, stupid things hold deep magic.

Ban Johnson and his umpires had tried to stop him, but Hughie Jennings was an early leader of baseball’s eternal insurgency of fun. In both Detroit and Chicago, the stands had bristled with a motley orchestra of noisemakers, while opportunistic vendors even sold “Jennings whistles” outside the park gates.

The officials could strictly enforce their rules on Jennings, but he was no longer alone: “Noise ran riot” during the World Series “ … and every man, woman, and child was equipped with some instrument that lent to the general din.”

If old Ban won't let him whistle, We'll whistle for him, you bet; And he'll know he's not forgotten By the fans who can't forget.

You know who could use some love right about now? Chicago White Sox fans. They haven’t had much to cheer about this season, when their team somehow managed to be both worse than the 1962 Mets and far less charming. What better time to dust off a wildly happy White Sox moment from happier times and give it the Project 3.18 spit and polish? That’s what we’ll do, next week.

On October 7: “Celebrating Ugly”

We tried and failed to figure out what exactly “shail” meant in this context. Our best guess is some kind of rocky or gravel patch, but don’t start saying it at parties or anything.

Tim Hurst seems like a treasure. An example of “old school” from 114 years ago, he had a disinclination to report misconduct to the league office, being of the belief that umpires should personally “settle up” with misbehaving players after the game was over, which means exactly what you’re thinking.

Another fun & educational article. I never heard of the monkey. Of course I was bummed out to hear about Pete Rose last night. I knew they were gonna screw him over before he passed! It was unfair to say the least. But anyway I loved your story Paul. Thanks again.

Interesting Paul. And not one mention of what was Hughie Jennings' special talent! Officially, the all-time leader in times hit by a pitch with 287. And befittingly there were a bunch in which he actually tried to get hit as was the custom pre-1900! Maybe his noise then was...OW!