Arms and Armor - Part 1

In 1941, major league baseball players started wearing helmets. All it took was an obsessive executive, a world-renowned neurologist, and a historic swarm of bean balls.

Eyewitnesses compared the sound to the report of a faraway rifle, but with soft, queasy edges. It was variously characterized as a crack, a thwack, or a thwock. But what made the sound unmistakable was its dreadful flatness. When a fastball struck a batter’s head, there was no echo.

In 1940 concerns for the batter’s safety reached levels not seen since the death of Cleveland Indians third baseman Ray Chapman, 20 years earlier. Ever since Chapman was struck and killed by an errant pitch, people had wondered what it would take for professional baseball to realize that players’ heads were worth protecting.

This is what it took:

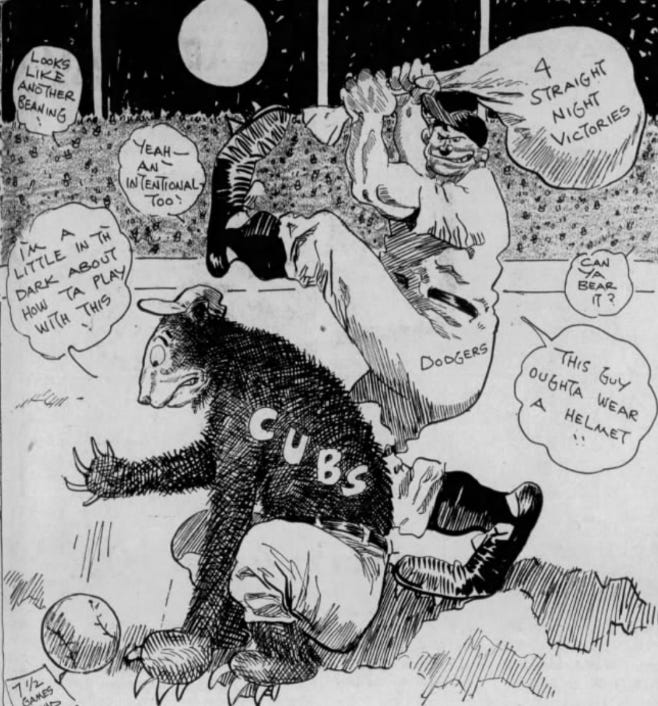

On June 1, Pee Wee Reese, the Brooklyn Dodgers’ promising rookie shortstop, was hit in the head during a game at Wrigley Field.

It was an accident; the ball “got away” from the pitcher and “sailed” inside. Reese said that he might have avoided it but he lost sight of the ball in the backdrop of people wearing white shirtsleeves in the packed Wrigley Field bleachers. To accommodate more fans, the park’s batter’s eye had been opened for seating. Reese’s injury was serious enough that doctors, wary of a sudden turn for the worse, refused to give an update on his condition for several hours after he arrived at the hospital.

“I never thought anyone could hit me in the head,” Reese said, “but that’s what happens if you can’t see the ball. I stepped right into it. They took me out on a stretcher, and I was out for 18 days.”

On June 18, Joe Medwick, the Dodgers’ newly-acquired slugging left fielder went down amid suspicious circumstances. During an argument in a hotel elevator earlier in the day, St. Louis Cardinals starter Bob Bowman had reportedly threatened to hit Medwick with a pitch that evening. Not only did Bowman hit Medwick, he hit him on the side of his head, sending the brand-new Dodger to the hospital. Brooklyn’s District Attorney, William O’Dwyer, went so far as to investigate the beaning as a possible crime. In the investigation, Bowman acknowledged making the earlier threat but said it was only trash talk; he insisted the subsequent beaning was just an awful coincidence. O’Dwyer quickly learned what baseball authorities already knew—it was almost impossible to prove that a pitcher hit a batter intentionally. The DA (a future New York City mayor) soon dropped the case and never spoke of it again.

On June 23, the same day Medwick returned to action, it was the New York Giants’ turn to lose a precious asset. Shortstop Billy Jurges was hit in the head by a pitch so high and hard that he was said to have had “no chance” to avoid it. When he woke up, Jurges found himself comforting the Reds pitcher, Bucky Walters, who was more upset than he was. Another accident, another lost month.

Three of America’s finest players, three hospital visits, three bedside pictures of bruised, bandaged men smiling reassuringly up at their alarmed wives. The United States wasn’t at war in 1940, but the rest of the world was, and Americans saw enough pictures from that foreign conflict see similarities in these images emerging from their national pastime. “The batter is flirting with the obituary column every time he steps to the plate,” a Brooklyn Eagle columnist named Ed Hughes wrote, “probably needlessly. It appears that a fracture-proof helmet is the only real remedy. Baseball, as an organized industry, owes such protection to its employees. To my mind it should at least be given a thorough trial.”

The biggest obstacle to such a trial were the reservations of the employees themselves. An armored cap, paradoxically perceived as “soft” and “weak,” infringed on some players’ vanity. Ask any player whether it was worse to get brained or be laughed at, and he would, at least, need to think about it. So it had been with every protective innovation.

The Giants’ Roger Bresnahan, who pioneered several pieces of catching equipment in the early 20th century, was ever the butt of such jokes. “There goes Roger, what kind of crazy contraption has he got on now?” But as the years went by people couldn’t help but notice how well Bresnahan was holding up. Unlike so many old catchers from previous generations, he seemed to have avoided the mangled fingers and bent limbs that were the curse of his profession. Eventually the players stopped laughing at Roger Bresnahan and started asking where he did his shopping.

The dilemma was more complex for hitters, engaged as they were in an eternal struggle for psychological dominance with the opposing pitcher. In this contest, courage was essential. Certainly every player was scared on some level; no player wanted to get “skulled,” but they had been taught to never show any fear. In that tradition, head protection became an admission of mortality, one that might tip a precarious battle of wills toward the pitcher.

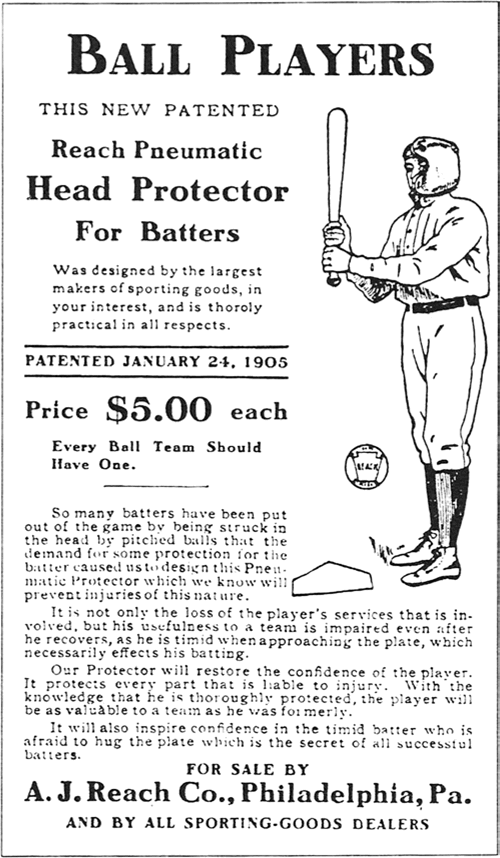

Still, helmets had been tried. Bresnahan wore one in 1907. As with so many of his firsts, this one was motivated by earlier miseries. While batting on June 18, he was beaned by a Reds pitcher and spent 10 minutes unconscious on the field. When he returned to action a month later, Bresnahan tried out something called the “Pneumatic Head Protector,” manufactured by a sporting goods company, A.J. Reach. Originally designed for firefighters, the PHP was essentially a little air mattress that wrapped around one quarter of the head. You put it on, then somebody else blew it up. Not even Roger could get comfortable in that setup, and from there inventors moved on to hard materials that could be made into thin, unyielding shapes.

Some players, current and former, cheered these innovations, however unsightly. Many believers had survived their own beaning or helped bear a teammate off the field. “It is better to wear a helmet than be carried away on a stretcher,” Hall-of-Famer Nap Lajoie said in 1940.

Lou Gehrig was more practical in assessing the helmet’s chances: “Helmets are a sensible, intelligent idea.” Therefore, he predicted, baseball players would never go for them.

Gehrig knew his people. After a rogue pitch ended the stellar career of Tigers catcher Mickey Cochrane in 1937, several players, including the Cardinals’ outspoken outfielder, Pepper Martin, put the beaning on Cochrane’s “carelessness.” Despite being nowhere near the incident in question, Martin claimed Cochrane “had taken his eyes off the ball because his head was turned sideways. If a dopey fellow stands brooding over his troubles he’s bound to get clipped.”

Some hitters seemed remarkably willing to blame themselves and end their own careers, if it came to that. “When I have to wear a helmet to protect myself at the plate,” a Reds player said in 1941, ”then I haven’t got any business playing ball and ought to go quietly.”

For their part, managers, executives, and owners usually encouraged players who wanted to wear protection. Since Bresnahan’s first, short-lived experiment in 1907 additional prototypes—typically with major aesthetic drawbacks—regularly found their way way into major league dugouts, peddled by sporting goods companies or motivated inventors looking to solve a pernicious problem and maybe make a little money.

“Our firm tried to put out a helmet,” a salesman reported in 1940. “It was a sort of light helmet guaranteed to protect a batter from glancing beaners.” Connie Mack, the manager of the Philadelphia Athletics, heard about the helmet and bought one. “He hung it up in the dugout and said any player who wanted to use it could. But it didn’t get any play to speak of, and we heard no more about it.”

Mack’s effort, though well-intentioned, was guaranteed to fail. No player was going to don a helmet while the rest of his teammates went without. The first half of the 20th century was littered with the debris of similar attempts, each one crushed by the limits of technology and the overwhelming forces of peer pressure. Yes, some of them might die, but it was a sacrifice the players seemed collectively willing to make.

The fates of Reese, Medwick, and Jurges did little to change their fellow players’ attitudes in 1940, but the epidemic of what one writer characterized as “near-death-in-the-afternoon” moved baseball’s leaders, who—despite the costs of paying salary to the convalescing and concussed—had previously seemed all too willing to let the players risk their skulls. In the wake of the Three Beanings it seemed like that might finally change.

In late June, with Jurges hospitalized and Medwick still suffering from dizzy spells, Ford Frick, the 46-year-old president of the National League, said he was tired of the many roundabout proposals floated in lieu of greater protection:

“They’ve suggested automatic suspensions, advancing all runners, awarding two bases, and automatic home runs. No use. Penalizing the pitcher won’t work. Most beanings aren’t deliberate. Most are caused by ‘sailers’ of rough balls and ‘freezeups’ by batters.”

The NL president was ready to try the obvious. “[Head protection] is the only way I know that we can prevent injuries, and the only way we can make the players wear them is to make it a league rule.” Frick said he was circling “a light helmet, worn over the baseball cap,” and planned to discuss the matter with the club owners at their traditional All-Star Break meeting in early July.

“If they should unanimously pass my measure requiring a batter to wear protection at the plate,” Frick said, “we would wipe out hospital cases and head injuries in short order. The way I look at it, the helmet will help the pitcher as well as the batter.”

It might even help both at the same time. On July 12, during an exhibition game with one of Brooklyn’s’ minor-league clubs, Dodger pitcher Hugh Casey was beaned while taking his at-bat, becoming Brooklyn’s third casualty of the year.

At their midsummer meeting the owners supported Frick’s idea in theory, but an idea was all he had to show. The helmet prototypes were not yet available, so any decision on a rule requiring their use would have to wait. The group agreed to revisit the issue over the winter, when Frick expected there would be something to look at.

In February, 1941, there was…something, all right:

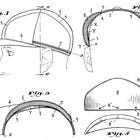

What would briefly be known as “the Frick Helmet” was more of a liner. It was constructed of buckram, the same kind of coarse, stiffened fabric that would soon be used to give the crown of a regulation baseball cap its upright bearing. Several accounts indicate the liner was to be worn underneath a player’s field cap, but photos exist of unhappy-looking players wearing it on the outside, with their soft cap crushed underneath it.

The Sporting News reported that a specific Brooklyn haberdashery had assembled the new helmet, which weighed between three and five ounces. Not bad, by weight, but its clunky aesthetics set players’ teeth on edge. Larry MacPhail resolved to fight for it anyway.

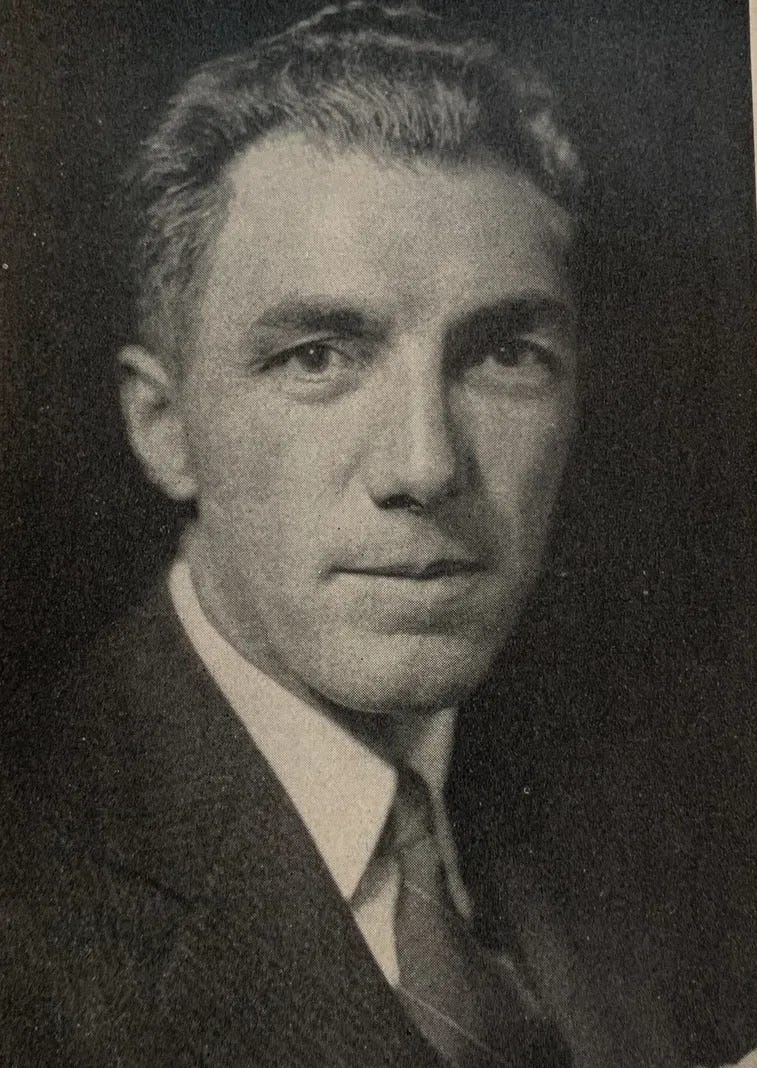

MacPhail, the bombastic president and general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, hated beanballs with a passion that suggested some past, unresolved trauma. He would try anything to stamp them out, including a yellow baseball, a 1938 innovation intended to improve the ball’s visibility. Despite the yellow ball’s mixed reviews, MacPhail (unsuccessfully) advocated for its widespread adoption.

When Joe Medwick was beaned in 1940, MacPhail became so angry that he marched down to the visitors dugout at Ebbets Field and challenged the Cardinals to come out and fight him, mano a mano. He found no takers, but his public declaration that St. Louis pitcher Bob Bowman hit Medwick on purpose created a scandal and two separate investigations.

Now, seeing a chance to bring helmets into baseball on a widespread basis and curb the beanball scourge, MacPhail brought all of his creativity, charisma, and volatility to bear in exhorting the other owners and executives to support Frick’s helmet, even posing for a photograph wearing one himself. But MacPhail privately worried that the league’s best effort would nonetheless repel the image-conscious players.

In February 1941 the NL owners voted to accept Frick’s helmet as a standard piece of equipment and pay to make it available to players during spring training for a kind of widespread trial. However, there was no appetite to make the helmet mandatory, even during the preseason. MacPhail stood behind Frick, saying the Dodgers would fully participate in this trial, but by his all-or-nothing standards this was tepid support. In reality, he was merely buying time.

While publicly supporting Frick’s adventures in hat-making, Larry MacPhail—with the help of two renowned physicians from Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore—had been running a side operation, trying to come up with something the players might actually tolerate.

Thanks to their collective efforts, there was another option; a secret option. With the start of the 1941 season a month away, MacPhail prepared to throw this new hat into baseball’s ring of fire.

As an early holiday gift for our readers, we’re going semi-weekly for this story, with installments releasing on Mondays AND Thursdays.

In Part 2: “A neurosurgeon, a chemical engineer, and a jockey walk into a ballpark…”

Seatbelts in automobiles were patented by Volvo and then opened the patent in 1959 for free use in the interest of safety for everyone.

At first they were an option in many vehicles. Customers didn't want to pay for them. So the US govt made them mandatory in 1968 to protect it's dumb dumb citizens.

Despite all the scientific evidence on the safety of seatbelts, including doubling your odds of dying in an accident by not wearing one, many people still refused to use them. Myself included. Yes, I admit to this. In my defense, I was a teenager and therefore immortal.

The government again had to step in for the safety of it's dummies. State laws starting mandating seatbelt use in the mid-to-late 1980s (in my state of Michigan it was 1985).

So as crazy as it seems to me to not want to wear a helmet to the plate, I can look back at my own history and realize how machismo can direct one's decision making. Almost always for the poorer.

On a personal note: my doctor told me I have low testosterone and offered to treat it. I declined, noting that every single bad decision I made in life was on high testosterone. :)

Really well done, Paul.

Fashion be damned! Safety first, Paul.