Arms and Armor - Part 2

How baseball's first modern “safety cap” was invented in the early 1940s. Just don’t call it a helmet.

This is the second installment of a multipart series on the first coordinated attempt to get major league batters to wear something to protect their heads. In Part 1 we covered a series of notorious 1940 beanings that pushed the National League to action, resulting in an unsightly protective liner.

Here’s Part 1, if you need to start from the top.

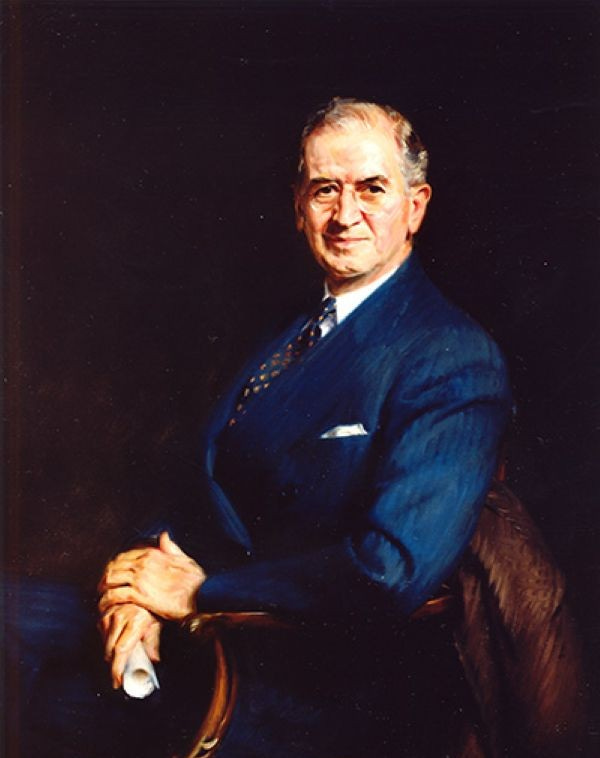

In today’s Part 2, the Brooklyn Dodgers’ president and general manager, Larry MacPhail, teams up with world-renowned doctors and petrochemical industry experts to come up with something a little more flattering.

In the winter of 1940, Ford Frick, president of the National League, had his hands full. Both leagues faced the looming threat of the Selective Service Act of 1940, which instituted a peacetime military draft and promised far greater disruption should the United States actually enter the second World War. Several players had already been drafted, including Hugh Mulcahy of the Philadelphia Phillies, who was the first, and Hank Greenberg of the Detroit Tigers, who was the best. The NL was also embroiled in a spat with baseball’s imperial commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, over club rights to minor league players.

On top of these headaches, Frick had promised to seek a leaguewide helmet mandate, but no helmet worth requiring existed as 1941 began, and the president didn’t have the time or resources to make one. Instead, he asked his close ally, Larry MacPhail, to come up with something. Anything.

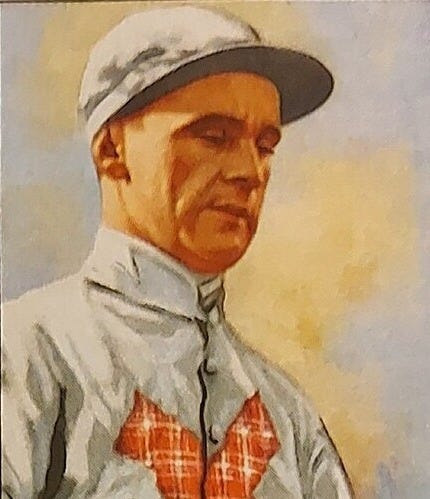

According to MacPhail, the first seeds of inspiration came from his friend, Alfred Vanderbilt Jr., an enthusiastic promoter of thoroughbred horse racing. So enthusiastic (and rich) was Vanderbilt that before the war he owned both Pimlico Racecourse and Belmont Park, two of the three legs of the prestigious Triple Crown. Knowing MacPhail was searching for a helmet that would work for baseball, Vanderbilt brought him a jockey’s light cap, which provided all-around protection while concealed under a colorful silk covering.

The jockey cap, though still too heavy, was a place to start. Now it was MacPhail’s moment to delegate. He turned to baseball’s Doctor to the Stars, a guy named George Eli Bennett.

Bennett, an orthopedic surgeon affiliated with Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, had long been part of baseball’s supporting cast. He had played semi-pro ball in his youth and kept a bat in his office, and his background helped him earn the trust of the clubs and their players. Bennett enjoyed becoming a baseball insider of sorts, though he hated the press scrutiny that came with being the doctor who decided someone like Joe DiMaggio had to have season-ending surgery. But he was usually right, and players like DiMaggio, Joe Medwick, Pee Wee Reese, and many others credited Bennett for helping extend their careers.

MacPhail sent the jockey cap to Bennett, “with the request that he indicate the parts of the cap which could be eliminated in order to reduce weight and still furnish protection.”

Bennett shaved off everything he could, notably most of the crown, or top. The idea was to fit the liner, made of stiff fabric, underneath a standard field cap, but the design was such that the bottom of the liner extended below the bottom of the cap.

Despite the concessions, Frick was pleased with the result, perhaps motivated by a desire to check this particular box and move on to other, more pressing issues. Bennett’s solution was presented to the eight NL clubs in early February and by February 4 they had made a deal to try them out during the upcoming spring training. Perhaps it was telling that no players were lined up to show off the new protector. Instead, Larry MacPhail wore it for the cameras, while the president of the St. Louis Cardinals, Sam Breadon, sort of picked at it on Larry’s head.

MacPhail smiled through the flashbulbs, but he knew he looked ridiculous, a feeling most players would not tolerate even at the risk of life and limb. “We thought it was too heavy, too bulky, and too conspicuous,” he said of the Frick helmet, “and did not feel it would be satisfactory to players.” Fearing this outcome from early on in the development process, MacPhail had pushed Bennett to work on another option.

Having reached the limit of his capabilities, Bennett tapped into the Johns Hopkins brain trust, seeking an expert on the physiology of the skull and brain. Those qualifications led him to Dr. Walter Dandy, one of the foremost neurosurgeons in the world at that time.

Described as “brusque,” “forthright,” and “a strict disciplinarian,” Dandy loved playing baseball in his youth but had no preexisting links to major league baseball. He came to JHH as a medical student in 1910 and never left, developing breakthrough techniques, such as a method for locating tumors inside an intact skull. In one notable episode from 1930, Dandy made news for demonstrating that “almost two-thirds of a man’s brain might be cut away without damaging his intellectual powers.” We’ll take his word for it.

Bennett came calling at the perfect time. Dandy was deep into his own “skull insurance” project, designing something that would give more protection to professional boxers during their bouts. This project, commissioned by the Maryland Athletic Commission, was doomed—boxers were even more stubborn than ballplayers—but Dandy had made some significant progress, and he agreed to throw in with Bennett and MacPhail.

The neurologist made an immediate impact, suggesting a material to make a protective baseball cap lighter and less obtrusive: plastic.

Dandy’s boxing protector would have relied on thin panels of a proprietary material manufactured by plastics technicians working for the DuPont corporation. Called “Plastacele,” it was a type of cellulose acetate, a kind of plastic that is derived from wood pulp. Today cellulose acetates are mostly used in synthetic fabrics, but they are also used to make frames for eyeglasses. The first plastic Lego bricks were made out of a similar material in the 1950s, so imagine two large, thin, pieces of primitive Lego and you are on the right track.

Dandy knew the panels he’d commissioned from DuPont could be precisely molded to hold a compound shape while “distributing the shock from a hard and swiftly thrown baseball so that it amounts to little more than the shock of a run-of-the-mill hailstone.” The first panels were reportedly a quarter of an inch thick but over time they would get thinner. They were an opaque, milky white, weighing an ounce each, and covered the side of the head from the temple to about an inch behind the ear. Following Bennett’s idea to prioritize key areas, Dandy proposed to insert a few of his protective plastic panels in the sides of a soft baseball cap and call it a day.

The first test models were reportedly stitched together by Dandy’s wife and daughters. From a visual standpoint, the results were outstanding. This was no contraption; it was just…a cap:

Seeing the prototype, MacPhail’s hopes soared and he rushed the specially made caps into production. Partnering with the A.G. Spalding Sporting Goods company, the first batch included zippered pockets, allowing the cap to offer protection on both sides of the head, one side, or neither. The design was far from perfect; Bennett was unhappy to leave so much of a player’s temples exposed and the ear remained vulnerable. But, in theory, Dandy’s hybrid head gear would provide as much coverage as the Frick helmet while looking 90% less ridiculous.

Eager to avoid the baggage of past efforts, MacPhail steadfastly refused to call the new creation a “helmet.” He preferred “protector for batsmen,” but that didn’t sound snappy enough for branding purposes. Thus did the last-minute creation become the “Brooklyn Safety Cap.”

The Spalding Company rushed the safety caps into production with remarkable speed, but not in time to debut before the Frick cap was adopted by the NL in early February.

On February 14, just days after the Frick helmet plan was adopted, two airplanes landed in Havana, Cuba, carrying MacPhail, manager Leo Durocher, and most of the Brooklyn Dodgers. The club would do their spring training on the island, then in the hands of a friendly government and a popular Caribbean destination for Americans. Government officials and a band welcomed the Dodgers at the airport and a police motorcade ferried them to the presidential palace for a tour.

The manufactured safety caps arrived several days later, by boat. Their design features reportedly caused some concern among Cuban customs authorities, who wondered if the zippered pockets were meant for some kind of smuggling scheme. It took MacPhail four days to straighten things out, but in late February the new equipment quietly arrived at Tropical Stadium in Havana.

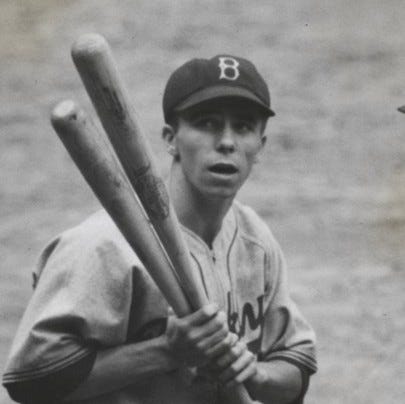

On March 8, 1941, MacPhail conducted a little experiment. Saying nothing to the press, he asked Reese and Medwick to wear Brooklyn safety caps during an exhibition game against the Cleveland Indians. The symbolism of putting these two players, who had survived grisly 1940 beanings, in the new helmets was powerful, but that was not what MacPhail had in mind. Quite the opposite: he told the players to keep quiet and just play.

Brooklyn battered Cleveland, winning by a score of 15-0, and with all the offense Reese and Medwick got to spend plenty of time with the merchandise. Afterward MacPhail asked the players to give the safety cap its first reviews.

“You’d never notice you had it on,” Medwick said. “There’s not enough difference in the weight or the feeling to bother anybody.” Reese had a similar reaction. But the best review came from the crowd, the press, and the other players. No one pointed, no one laughed. In fact, no one noticed at all.1

After the game MacPhail gathered the test subjects and held a triumphant press conference, showing off the Brooklyn safety caps and his satisfied customers.

“No one noticed the players wearing it,” he bragged, “and shortly thereafter [pitcher] Freddy Fitzsimmons wore it while throwing batting practice.” No one noticed Fitzsimmons’ cap, either.

“Both Pee Wee and Joe pronounced the helmets 100 percent okay,” MacPhail told reporters. And even though boxes of Frick helmets were being delivered to camps all over the Western hemisphere, MacPhail was ready to declare it obsolete.

“The objection I heard from other club owners was that the players would never wear [the Frick helmet],” he said. “They wouldn’t wear a thing that was cumbersome and so conspicuous that everybody could see it. Well, my players are solid for this one, and they’re all going to use it.”

Every player in the Brooklyn organization would wear one, he announced, from the big stars to the lowliest benchwarmers in Class D. At the big league level, players who batted unprotected would be assessed a $100 fine.

MacPhail saw the new caps as “the biggest thing that’s happened to the game since night baseball” (another innovation he had pioneered). They were so unobtrusive that he allowed himself to hope they might catch on even without a leaguewide mandate. The Dodgers could show the rest of the players that safety didn’t have to be an embarrassment, and when that sunk in, the dominoes would begin falling. “Every player in the majors will be wearing this helmet within a year,” MacPhail promised.

Between Bennett, Dandy, Dandy’s family, the DuPont technicians, and the horse guy, at least a dozen people contributed to the development of the first viable head gear for batters. For his part, Bennett didn’t mind seeing his earlier effort, the Frick helmet, quickly discarded in favor of something that was unquestionably more sophisticated.

“The credit belongs almost entirely to MacPhail,” the doctor said, later in life. “MacPhail liked the idea, but, most important, he pushed it.” If he was anything, Larry MacPhail was a pusher.

The Chicago Tribune described MacPhail’s helmet order as “the climax of the campaign for protection against both accidental and deliberate bean balls,” but the safety caps had come together so late and so quickly that there had been no time for field testing. To find out how much safety the new caps actually provided, some unlucky Dodger was going to have to risk disaster.

For better and worse, Brooklyn had the perfect guy for such a hazardous assignment. His name was Pete Reiser, and he needed all the protection he could get.

As an early holiday gift for our readers, we’re going semi-weekly for this story, with installments releasing on Mondays AND Thursdays.

Part 3: “Pistol Pete takes a bullet.”

Remember those pictures we showed, of Dr. Bennett’s famous Dodger patients, Reese and Medwick? That was our little experiment. We chose those two particular photographs, from later in the 1941 season, because Reese and Medwick are shown wearing Brooklyn safety caps. Did you notice?

I didn’t notice the Brooklyn Safety Caps, but you got me to scroll back and look, and yep, that’s what they were wearing! As far as Pistol Pete, I don’t think of Pete Reiser, rather basketball great Pete Maravich pops in my head, who played for the Atlanta Hawks in the early seventies, and for LSU in his college days. I don’t like waiting for Monday because this story has me hooked! I am dreading the next beanball, because that plastic material probably doesn’t dissipate the shock and there just isn’t enough coverage. I will do this the old school way; I’m not going to Google the history of the baseball helmet, and am going to let the story play out with your telling.

I remember Pete Reiser as a coach later with the Cubs - those guys hung around forever.