Cash Grab - Part 1 of 2

When baseball’s popularity waned, a creative and determined promoter threw money at the problem...but only in small bills.

We’re back! Offseason’s greetings, and may all your freed-up time be joyful. Winter sure is a great time to catch up on some quality reading.

It may be the offseason, but Project 3.18 is on a twelve-month baseball calendar, so we’ll continue to appear in your inbox weekly with a little bit of summer. Thanks for having us.

We’ll continue to deliver baseball stories you aren’t going to find anywhere else—strange and surprising tales from the game’s extensive back catalog, and that’s just what we’ve got for you today. After spending most of the postseason way outside our comfort zone (with back-to-back stories from the 21st century), we’re starting the winter with a deep dive into a 20th-century fad.

1967: Something Borrowed

As far as we can tell from a week’s worth of intense, semi-professional research, the first major league team to throw cash money all over the sacred preserve of the infield was the Houston Astros.

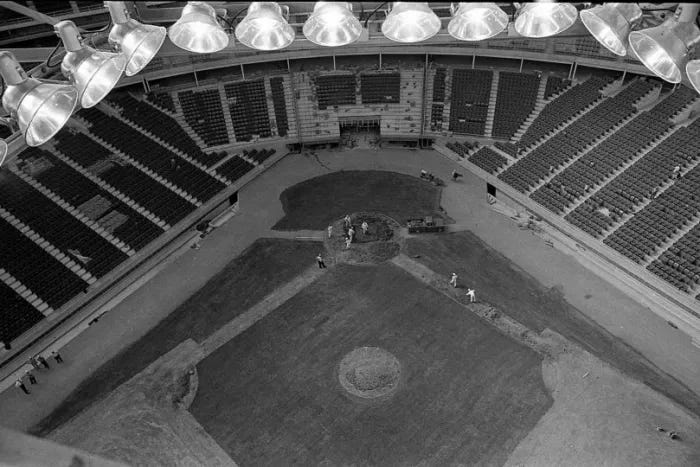

The Astros held their first “Cash Scramble” in 1967, during a home game against the Philadelphia Phillies on July 24. It was “Bank Night” at the Astrodome, and all fans in attendance would receive a souvenir piggy bank in the shape of the futuristic sports temple. Before the game, a few lucky fans would get to scramble for $1,000.

The rules that night established a standard for the promotion. Astrodome employees spread 900 $1 bills and a single $100 bill (to stimulate urgency) on the infield grass, and three fans would have an opportunity to temporarily set aside decorum and dignity and scoop up much money as they could in a few minutes of frenzied action.

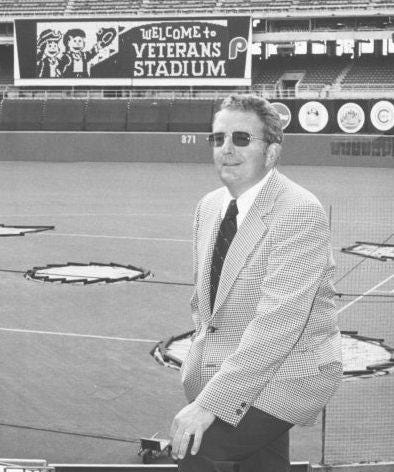

The cash scramble was a product of the improvisational and irreverent mind of the Astros’ promotional director, a lifelong baseball man named Bill Giles. Giles, 33, was the son of Warren Giles, the National League President at the time, and he had literally been raised inside the sport. Giles the Younger got his professional start with the Cincinnati Reds in the 1950s when his father was the general manager of that team. He came to Houston in 1962, along with several other rising stars from the Reds’ front office, tempted by the opportunity to help put the expansion Colt .45s on their feet.

Unfortunately for Giles and the other Reds ex-pats, the expansion draft used to stock the Colt .45s with players from existing teams was so weakened and watered down that it would be several long, lean years before Houston could expect to be competitive. In the meantime the club was going to have to give fans other reasons to come out to the ballpark.

“Let’s face it,” Giles said in 1967, “when you’re losing, you promote. When you’re winning, you don’t have to.”

Giles and the Astros were promoting in the summer of 1967. Never mind the fact that the team had yet to have a winning record; instead, fans were subjected to what writer Wells Twombly called “an all-out assault on the customer’s imagination.” In July alone, the team held a Millionth Fan Night (cumulative), Button Night, Scout Night, Straight-A Students Night, a Miss Astro Contest, and even a softball exhibition pitting members of the Houston press corps against the radio-TV brigade.

In addition, the schedule was peppered with giveaway nights, or, as Twombly put it, “two solid weeks of a bombardment of ornate boz-woz.” Giles used one of these, “Helmet Night,” to explain the basic economics of promotion:

We gave away 12,000 helmets that cost us about $4,200. That’s a pretty sizable investment, but it paid off. We got about 6,000 more fans than we expected. You can guess that added about $18,000 to the gate. So we made an excellent profit.

And there was a knock-on impact, here at the dawn of team-licensed apparel. After a helmet giveaway, helmet sales picked up: “Seems one kid would go home and tell all the kids in the neighborhood where he got the helmet. So every kid afterwards wanted a helmet of his own.”

Giles also gave a report on the results of the Astros’ first-ever Cash Scramble. The three contestants picked up less than $500 between them (the $100 bill went unclaimed) and attendance that night was 6,000 more than expected. $500 had turned into $18,000. The fans might as well have put their own money on the field and let Giles gather it up.

Giles said the scramble promotion had been “borrowed” from a minor league promoter named Joe Engel, who had done something similar in the 1950s while he was making the AA Chattanooga Lookouts one of the most interesting tickets in any league. We may circle back to Engel’s “Cash & Carry,” but let’s stay with the majors for now.

And though it had bush-league roots, Giles’ cash scramble performed wonderfully in the majors, and, so long as the Astros remained rather bush themselves, the promotion was staying. In 1968 the team moved it to a prime-time position before the Fourth of July game, with fireworks to follow.

In 1969 the “third annual” Cash Scramble was held in early May. Three randomly selected fans were given just 90 seconds to grab the money. The Astros would continue the promotion into the 1970s, but 1969 was the last year that Bill Giles oversaw the club’s promotional calendar. In 1970 the Philadelphia Phillies poached him to be their vice president of business operations. The Phillies were soon to move from Connie Mack Stadium, the derelict baseball palace, to a state-of-the-art new park, Veterans Stadium, and the team wanted a business leader with a bit of flair.

With Giles in transition there was a lull in major league scrambles, but the Astros carried the flickering torch, holding a barely mentioned event on May 8 that attracted no surplus fans. What had begun as an enticing stunt seemed on the verge of growing stale.

1971: Bread and Carnivals

As television cameras proliferated and football took over as the nation’s most popular sport, many baseball teams were scrambling for ways to draw crowds they’d long taken for granted. Promotional events littered home calendars, inserted into doubleheaders, juicing big series, or trying to salvage a clash of also-rans. Once islands in an ocean of baseball, fans could now cross the entire season on promotions without ever getting their feet wet. “It’s gotten to the point where people won’t go unless they’re giving something away,” a San Francisco Giants executive complained.

Many old-line baseball men were unhappy. “It’s degrading,” one said. “It’s stopgap, panic-type promotion. Even the clubs that do giveaways wish they didn’t have to.” This statement contained some projection. In fact, several clubs were all-in. The Los Angeles Dodgers were one of the most financially successful (and popular) clubs in this era, but the ruling O’Malley family was nonetheless doubling down on promotion. That summer the Dodgers held the first-ever “Helmet Weekend,” with plans to give away 100,000 helmets and capture the hearts of Los Angeles’ children for a generation.

Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, baseball’s senior fun-ruiner, was asked about the fad transforming baseball’s business and his response seemed unusually tolerant (this was because promotion was helping teams make money).

“If you ask me I would just as soon see baseball do without the giveaways,” Kuhn said, protecting his dignity even as he prepared to sell out. “At the same time, I think that baseball has a different atmosphere than any other sport. There is a carnival feeling to baseball. I think it comes down to this: If the promotion is done in good taste, then I’m for it.”

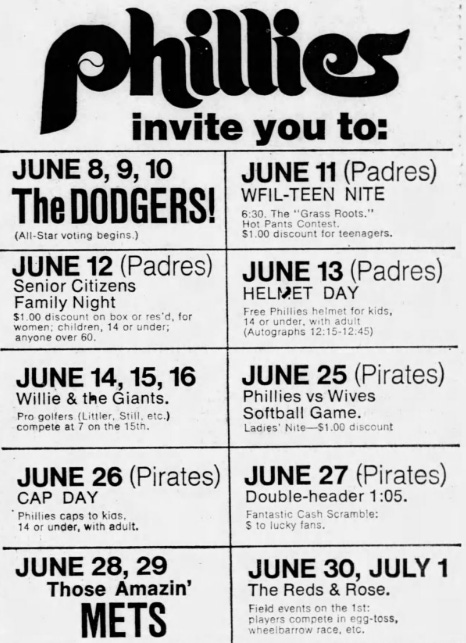

And while Dodger promotions were always tasteful, with a year under his belt in Philadelphia (and with a last-place team to prop up) Bill Giles was going full-carnival, as evidenced by this promotional calendar from June 1971:

Here is a promoter nearing the top of his game. We see the Cash Scramble, now “Fantastic,” having made the trip east in Giles’ bag of tricks; and we see other classics, including Cap Night, Helmet Day, and an intergender softball game between the Phillies’ players and their spouses. Because this is 1971, there’s even a “Hot Pants Contest,” on June 11.

Even the man who had hired him, the Phillies owner, Bob Carpenter, found the Gilesian promotional calendar to be a bit much. “Bob would listen to one of my ideas and say, ‘Jesus, why do we have to do that?’” Giles recalled. “I’d just say, ‘Bob, we’re in a huge new ballpark with a lousy team. We’ve got to do a lot of things to get the fringe fans we’ve lost to come back.”

Giles continued to iterate in 1972. The wives’ softball game got more competitive, pitting the Phillies’ wives against the wives of the visiting Mets. The team hosted “Surf and Sand Day,” tempting residents of a city with no on-premises surf or sand with $18,000 worth of beach stuff, from sailboats to surfboards and even a dune buggy. As if that wasn’t enough, all “youths”—liberally defined as anyone age 19 and under—would receive a complimentary frisbee.

On June 10, the visiting Braves put a huge hurt on the Phillies, as Hank Aaron hit his 649th home run and took sole possession of second-place on the all-time home run list, beginning what would turn out to be a grueling 22-month odyssey to reach the top spot and unseat Babe Ruth. Given the drubbing on the field, the highlight that night was surely the returning Cash Scramble, the prize pool now pumped up to $2,000. According to one observer, one of the three lucky fans selected to participate was a nun, who produced the night’s second-most memorable sight (after Aaron) when she joined two other women in a hands-and-knees showdown on the AstroTurf surface of Veterans Stadium.

The Phillies continued to innovate in 1973, presenting an Amazing Cash Scramble in between two games of a June 26 doubleheader against St. Louis. “Amazing” was a stretch, but this time five fans could participate, plus the team was adding a “Change Scramble,” in which, as best we can tell, fans competed to haul off the largest sack of loose change.

It had taken half a decade, but the rest of the industry was finally taking notice of Giles’ success with his pet promotion, which had twice become a ballpark tradition and occasional cash cow. Scrambles, once relegated to the minor leagues, were about to blow up.

1974: The Golden Age of Gimmickry

The Cleveland Indians were first to light a fuse, announcing their (more formal) “Money Scramble” would be held later that summer. The Indians had tanked on the field and at the gate in 1973, so badly that there were real questions if the city could sustain a team going forward. The Indians’ promotional staff, led by a whiz kid named Carl Fazio, Jr., was going all-out to boost attendance and stifle the murmurs of relocation. Yes, there would be baseball, of some unknown quality, but—forget the carnivals—Fazio was determined to turn Municipal Stadium into a three-ring circus, with promotional activities lined up for nearly every other home game. It was no coincidence that the Indians added a cash scramble; their promotional onslaught had been inspired in part by a fact-finding trip to Philadelphia.

“We want to make the ballpark a very entertaining and exciting place again,” Fazio said that spring, “and we think a good schedule of promotions will do a lot to complement the games. We’re shooting for a million attendance; that’s no secret. [Hitting that target] depends on so many things…it’s all part of the show.”

The show would feature, among many other things, a man being shot out of a cannon and a different man walking on a metal wire stretched across the roof of the ballpark. There would be giveaways of all shapes and sizes and the team was bringing back a popular discount beer promotion, not once but four times in 1974 (at least, that was the plan on paper). The Money Scramble was planned for June 28, when three fans would get a crack at $2,000.

Meanwhile, the Astros were still at it, and in 1974 the game and the promotion would come together in a perfect moment of Texas-sized spectacle.

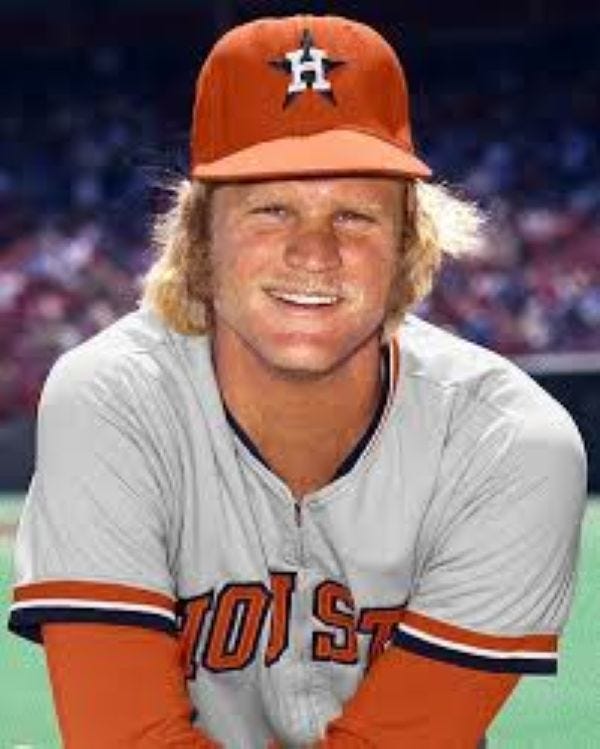

This was the tail end of the “Big Orange” period, when the Houston players looked like Dreamsicles and the club tried to do its own version of a “Big Red Machine” with vastly inferior parts. And while the franchise appeared to be turning a corner—with winning records in 1972 and 1973—the Astros continued to lean hard on promotion, and May 22 would be “Ladies Night,” with discount entry for women, along with a special competition:

Every woman wearing Orange will be allowed on the field to participate in the Cash Scramble as $1,000 will be dropped from the gondola at the top of the Dome to the AstroTurf below. Then watch those gals scramble for the green, thanks to the Orange.

The “gondola” was a circular walkway suspended just underneath the center of the dome, several hundred feet above the playing surface. The Astros were going big.

Approximately 1,000 “gals” turned out in their best 1970s orange. The participants were told to gather at a certain spot in the stadium near the end of the game and wait. As soon as play concluded the money would drop and they would be allowed to charge out onto the playing surface to catch as much as they could.

When the entrants began gathering in the late innings the Astros were still locked in a 1-1 tie with the San Diego Padres and for a moment it appeared the Cash Scramble would have to stand by. In the bottom of the ninth inning the Astros managed to load the bases. There were two outs when catcher Milt May pinch hit, taking the last at-bat before the game went into extras. “All I wanted was a base hit,” May said. The catcher hadn’t had much success as a power-hitter, especially in his home park. “It’s probably the toughest park in which to hit home runs. All I can do with mine is scrape the back of the wall.”

And that, of course, is just what May did, hitting a wall-scraping, walk-off grand slam and sending the crowd into delirium. As May rounded the bases the Astros dumped the money and gave the “go” signal to 1,000 orange-clad revelers. If Bill Giles had been there, his soul would have left his body.

The celebrating Astros retreated to their dugout, as did the vanquished Padres, all of them staring at the pandemonium on the field as dollar bills sailed in all directions with at least two women chasing after each one. Thanks to Milt May’s impeccable timing and the team’s creative use of their unique home ballpark, Cash Scramble ‘74 was going to be a hard stunt to top.

Two weeks later Cleveland said, “Hold my beer,” and gave the world Ten Cent Beer Night.

Here’s the conclusion:

Over on the Podcast:

And on Clear the Field, we had a great time dissecting Joe Niekro’s personal grooming habits and our own personal conspiracy theories.

Plus, a new episode drops this Thursday! Hint: We’re sticking with 1987.

I thought for sure this was going to be a Bill Veeck story. Never heard of this before, Paul. Great stuff! Now I’m hoping to find some video.

Everybody loves free stuff… no doubt about it. Maybe an alternative would be free food (2 hot dogs maybe) or maybe reducing ticket prices so a family can afford a game.