Cash Grab - Part 2 of 2

The history of baseball’s “cash scramble” promotion, from the highest highs to the lowest lows.

Today we’re finishing our deep dive into baseball’s “cash scramble” promotion The scramble was unveiled in the late 1960s but really took off in the 1970s, and this installment picks up in 1974, when the fad spread across the majors from coast to coast.

Here’s Part 1 of the story; you’ll want to read that first!

“Now I’ve heard it all,” a wary national columnist wrote on June 26, 1974.

Those Cleveland Indians, who were more than partially responsible for that riot during which the Texas Ranger players were attacked by the fans, are about to run a “money scramble” after their home game with the Red Sox on Friday.

Keep your eye on this one.

Could Cleveland be trusted to responsibly manage this kind of excitement? In the wake of Ten Cent Beer Night, the June 4 beer promotion that ended in a calamitous forfeit, doubting Cleveland was very much in vogue. But Carl Fazio, Jr., the Indians’ director of sales and marketing, trying to draw a million fans, was determined to press his spectacle offensive.

Cheap beer promotions were currently on hold, pending American League review, but no other stunts had been banned, leaving Fazio and the Indians free to host clowns, choirs, and, according to one observer, exhaust all promotional possibilities “short of a public execution.”

“When,” an anonymous player grumped, “do they bring in the donkey?”

The donkey, in Oakland, was trademarked and therefore unavailable, but Cleveland’s first money scramble would proceed as planned on June 28.

Even the Indians’ players were pitching in—by playing surprisingly good baseball. The team was 36-33 at the end of June, good for second place in their division. Much of that success was coming courtesy of pitcher Gaylord Perry, who had won 13 consecutive starts and was threatening the American League record of 16 straight pitcher wins. By virtue of an excellent forkball, a superior slider, or some cleverly concealed lubricant, Perry was threatening to put baseball back in the center ring of Fazio’s Cleveland circus.

Only the weather stopped June 28 from being a huge night at the gate. Heavy rains earlier in the day delayed the game a full hour, but 33,000 people came anyway, lured by the chance to see Perry win 14.

“I was hoping for 50,000 tonight,” the Indians’ chief executive, Ted Bonda, said. “But this turnout, considering the weather, does show something. There’s definitely a revival of baseball interest in this town.”

The wet conditions left the field unsuitable for scrambling, but Perry did what he could to make it up to the fans, pitching a complete game and allowing just three hits. A George Hendrick walk-off double sealed a 2-1 Cleveland win and moved Perry’s record to 14-1. Nobody went home any richer, but everybody left happier.

Cleveland rescheduled their scramble for a few days later, lining it up with another promotion, “Family Night,” wherein the “head of household” would pay full price while all associated spouses, children, and live-in grandparents got in for half-off. In front of that domestic crowd, three lucky fans, chosen at random by ticket number, would scramble for $2,000 while the sporting world held its collective breath.

And things went…fine!

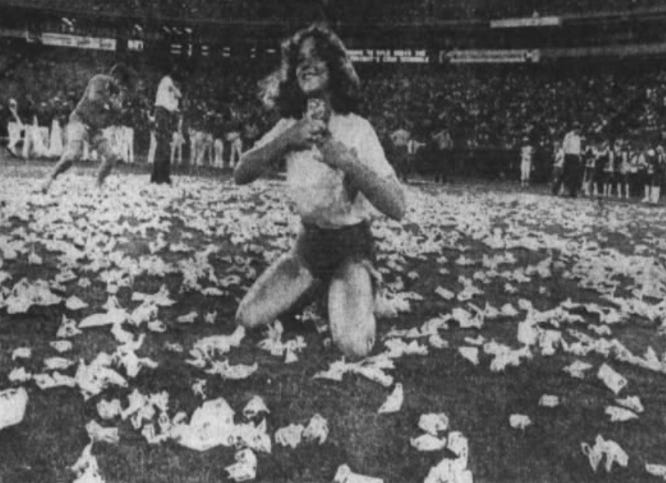

The three scramblers were Tony Overly, age 7; Debbie Brown, age 15; and Ella May Scott, an adult of sufficient age that it was not polite to ask. The Indians’ promotional staff distributed the two grand and a kindly camera operator handed Debbie Brown an equipment bag to use—her short-shorts and halter top left her without a realistic place to stuff any cash. The three combined to collect $582. In a classy touch, the Indians donated the unclaimed remainder to the American Cancer Society.

When the night ended, Fazio was nearly halfway to his goal of a million fans, and was already more than 100,000 over the apocalyptic sales of 1973. No matter what happened, he’d weathered the disaster of Ten Cent Beer Night and proven that there was plenty of hope for Cleveland baseball.

From that perspective, the team’s cash scramble was almost a noble deed. It would have been all too easy for the team’s ownership to say the town had given up on the team and pick up stakes, bound for somewhere exotic, say, Seattle, Denver, or Toronto. But the Indians did the opposite, rolling up their sleeves and embracing what Bowie Kuhn had described as baseball’s “carnival side.” Even the commissioner himself had noticed. Unfortunately.

On August 1, Bonda, the Indians’ senior official, heard from Kuhn by mail:

Dear Ted,

Several weeks ago, your club staged a fan scramble for money scattered about the field. I have intentionally let some time slide while I thought about whether I should write you on this subject. While I am quite reluctant to get involved in club promotions and while I believe that imaginative marketing is a critical need of our game, I have a real concern about the desirability of this particular event. Even though it has been used in the minors, I think it reflects badly upon the image of Major League Baseball and that is something about which I have to be concerned as all of us have a common stake in that image. I would appreciate your giving serious thought to the views I have expressed in this letter.

Sincerely yours,

Bowie Kuhn

Cleveland just could not catch a break. Bill Giles was soon to stage his seventh “fan scramble for money,” in Philadelphia, but here were the Indians catching a stray scold, as if the offending stunt had been lifted right out of the lost diary of General Moses Cleaveland himself.

It was unfair, but Ten Cent Beer Night had put a target on the organization’s back, especially when it came to promotion. For a few months that summer all of the game’s huckstering, hustling sins were laid on Cleveland, where taste was apparently optional.

The Indians finished the season with an 77-85 record and 1.1 million in attendance. With Fazio spinning every plate he could find, the club had its best box office showing since 1959. It was a victory for the little guy, and a timely one, because the big guys were about to get involved.

The San Diego Padres were under new ownership in 1974. The woebegone team had been acquired by Ray Kroc, better known as the Found and Chairman of the McDonald’s Corporation. At 72, Kroc was taking at least a half-step back from his duties at McDonald’s and looking for new, part-time challenges.

The Padres certainly qualified. Having lost 102 games in 1973 the team drew such little interest when it hit the market that it was almost sold to a consortium based in Washington D.C. Kroc stepped in late in the process in order to keep the team in small-market San Diego.

Kroc, who would have been worth somewhere around $500 million in 1974, had an uneven first year as a club owner, typified by an incident on April 9 when a Padres’ miscue drew Kroc to the public address microphone, which he used to berate the players (“This is the most stupid baseball playing I’ve seen my life!”) and apologize to the fans.

The outburst didn’t endear Kroc to his new employees but it went over great with the frustrated fans, who believed the team finally had an owner who would try, and attendance picked up.

By the end of June, the Padres had already passed their all-time season attendance record, and the owner reportedly wanted to give something back. “Mr. Kroc wanted to show his appreciation to the fans for breaking the attendance record so early in the season,” a team official said. The Padres announced “$10,000 Cash Jackpot Night,” scheduled for a July 14 game against the Montreal Expos.

Kroc’s five-figure scramble also expanded the participant pool to 20 individuals, to be symbolically chosen from five different sections of San Diego Stadium. Each contestant would be issued a shopping bag with which to hold their loot, avoiding any unseemly stuffing of shirts and pants. An armored truck added a little theater, bringing the bags of money—in denominations from $1 to $20—out onto the field for distribution. There was even a single $1,000 bill for one lucky fan to find.

Jackpot Night was also the first scramble that proceeded using fake money, to deter any overeager volunteers from joining. The contestants would turn in what were essentially chits after the event and walk away with a check.

The new procedures helped Kroc’s Thank You go off smoothly, despite the larger and more tempting amount of money in play. Two minutes provided quite enough for the 20 chosen fans, who scooped up all but $114 of the cash.

One lucky fan found the $1,000 bill and carried away $1,521, three times the average “share” of the pot. There was just one small problem: Raynald Savoie was an Expos fan, having traveled from Montreal to San Diego with the Expos’ booster organization. Ray Kroc said “mille mercis” and paid Savoie off anyway.

Jackpot Night was framed as Kroc’s kindness, but consider that $10,000 amounted to .002% of the fast food mogul’s estimated net worth at the time. If you were worth, say, $1,000,000 and wanted to make a comparable gesture it would cost you 20 bucks.

But even this miniscule generosity was theater—Kroc had set the team up to be financially independent, and the ten grand came out of its promotional budget. That expenditure yielded a tidy profit when 17,000 fans bought tickets on a Friday to see a last-place team.

Bill Giles and the Phillies seemed to not know they were in an escalating arms race. Or perhaps the fact that the team was in first place led them to stay out of the fray. The team did hold its traditional scramble in late June, but Giles’ original recipe now failed to inspire. Three fans? 90 seconds? Just $2,000? Where was the old showmanship?

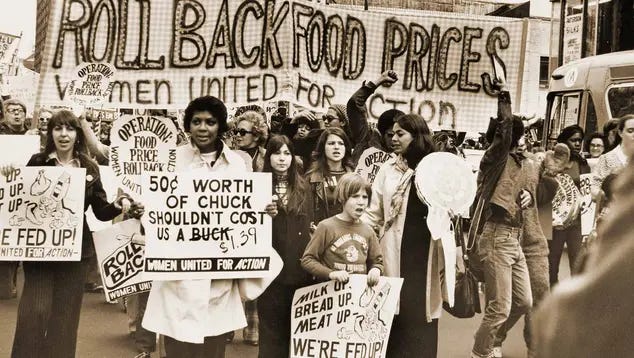

The formula had never really been fresh, not when it was appropriated from the minor leagues circa 1952. But the optics around the cash scramble had shifted significantly since its major-league debut in 1967. America had entered a pronounced and protracted economic downturn and in the fall of 1974 the storm was expected to get even worse. With manufacturers and retailers poised to respond to relentless inflation by raising prices on everything, Americans were warned to buy now and prepare for “sharp” increases that fall.

Food prices were growing and not just fresh, premium products. Canned goods were doubly hit; the cans were more expensive, too. The art of buying groceries on a tight budget was revived.

A cotton shortage was driving up clothing prices. Home and auto repair costs rose and forget about buying new; there was a shortage of materials and labor. And all of this was before the impact of ongoing petroleum price wars in the Middle East, certain to bring big markups to everything that used oil, gas, or plastic. In this context perhaps the cash scramble, unseemly to begin with, was now hitting too close to home. Some people certainly thought so.

“In a time of escalating prices and inadequate wages, I was sickened at the decadent throwing of thousands of dollars on a baseball field,” a Cleveland woman wrote in the Plain Dealer after the Indians’ scramble. “I wonder, too, what we are doing to the self respect of those involved in the contest. It is certainly a step backward to promote cheering as women crawl and grasp for money or to teach a child that it is OK to make a fool of himself in front of 30,000 people if there’s money in it.”

To attract distracted fans, baseball had increasingly abandoned its dignified pedigree, and this strategy worked well for a time. But as the 1970s went on there seemed to be a nationwide shortage of dignity, too. In that context, the sight of people “crawling and grasping” for money—in amounts that the team owners (and soon some of the players) wouldn’t bother bending down to pick up off the street—well, maybe Bowie Kuhn was right about this one.

1975: “Don’t Choke”

That was the message from the Atlanta Braves in July 1975. Try not to do a spit-take, Braves fans, but “YOU could be a big winner in the $25,000 Cash Scramble!” Six fans, 90 seconds, and a format that generally copied what the Padres had done the year before, featuring play money, a $1,000 bill, and an armored truck, now with even more cash.

The resulting promotion “was fairly successful,” the Atlanta Journal wrote. “The six contestants grabbed a total of $3,705. No one got hurt. No one rioted. No one—yet, anyway—has sued.” Such were the standards of the times. One of the hopefuls, an 11-year-old girl from Columbus, gathered $288 and was sure “I could have gotten a lot more if I had a bigger shirt” in which to stuff it.

The cash scramble’s drawing power seemed to be waning as it neared a decade in rotation. The last-place Braves drew only 10,000 fans on July 25, and there was so much play money left over that the team desperately threw another scramble on the schedule for mid-August; only 4,700 fans showed up for that one. The Braves were on track to have their worst year at the ticket office since the team’s final year in Milwaukee in 1965.1

The team’s competitive prospects had collapsed and Hank Aaron wasn’t chasing anyone’s home run record. Aaron wasn’t even around—he was back in Milwaukee with the Brewers. Bob Hope, Atlanta’s promotions director, acknowledged that the scramble was a part of a rearguard action:

We’ve given away every item imaginable. Right now our major problem is performance. It’s not near as much fun to lose as it is to win. And if you look at our record, some 25 or 26 games out of first place, it’s not hard to understand why fans stay away. This year everybody is in a slump and the city is in a recession. Right now we’re fighting for the hundreds as opposed to thousands.

Just like the scramblers.

In Houston, the Astros tagged their annual scramble onto “Ladies and Senior Citizens Night,” but nobody had to wear orange and the thousand bucks was just dumped out on the field. Short of ripping a hole in the Astrodome roof and dropping the money from a hovering helicopter, the Astros’ cash night had literally hit its ceiling in 1974, and now there was nowhere to go down.

1981: “The Team Got Good”

Between 1976 and 1980 the Braves and Phillies scrambled on. For the Phillies it was a matter of tradition, but for the cratering Braves it was a matter of desperation, forcing Bob Hope to take over as the game’s most renowned purveyor of questionable antics.

The cash scramble’s big-league career seems to have ended in 1981, when the Toronto Blue Jays, arriving at the bar after the staff had begun putting up the stools, held three consecutive cash scrambles on the final three home dates of the strike-shortened season, with $10,000 up for grabs each night (if you stuck around for the end of the games).

What started with actual bills in 1967 had been progressively watered down, first to “play money” in the 1970s and now to bags of shiny plastic tokens in Toronto, which the Jays spread on the infield of Exhibition Stadium after the games. The scramble itself seemed rather mean-spirited for Canadian sensibilities, as one writer observed from high up in the press box:

I watched a man in his 60s picking up tokens, dropping them into his plastic bag, then the bag broke, and two other fans moved in and…robbed him. There is no other word for it. As the tokens spilled out of his bag they snatched them up and stuffed them into their bags. I’ve never seen a mugging in public.

After that last gasp, the cash scramble and any number of other equally shameless baseball promotions were largely thrown back into the minor league swamp from which they had earlier been fished.

Perhaps it was just a generational change in tastes, but there were business reasons, too. Television contracts had gotten bigger, padding profit margins and reducing the urgency to fill physical seats by any means necessary. And the proliferation of moving image recording devices at the ballpark led surely teams to reconsider earlier tactics. It was easy to imagine a nightmare scenario in which footage of a nun stuffing Monopoly money into her habit played on the national evening news and then the Tonight Show.

1981 was also the year that Bill Giles joined an ownership group and successfully purchased the Philadelphia Phillies. Promotions in Philadelphia had slowed down dramatically in the late 1970s as players like Steve Carlton, Mike Schmidt, Tug McGraw, and Garry Maddox made the Phillies regular contenders. The team won the World Series in 1980 and that sort of accomplishment tended to promote itself.

As he took over the team in 1981, Giles was credited for “shoving the Phillies into the 20th century.” Born and raised in the grand old game, Giles could recall a time when his father’s Cincinnati Reds promoted their games merely by hanging a sign outside Crosley Field displaying the start time. When he himself got into the business, those days were over, but Giles adapted, giving the fans what they wanted at the time: surprise, spectacle, and more than a dash of irreverence.

“I created a lot of crazy promotions,” he said in a 2007 interview, “with the philosophy that if we could get [people] in there once to see whatever the crazy promotion was, that they would like the experience and then come back when there was just a little old ballgame.”

New podcast episode is up! Ted and I are sticking with the 1980s and exploring a modern version of a very old promotion (with the same inevitable result):

The Braves had hoped to make 1965 their first season in Atlanta, but protracted legal wrangling essentially forced them into playing one more desultory year in Milwaukee. That must have been a really tough year for promotion: “Come see your Milwaukee Braves…here by court-mandated settlement!”

It is difficult watching your team lose over & over but the true fans should back their team… problem is at least at today’s prices going to the park is not what every one can afford. And a family??? Forget about it.

Bowie Kuhn was no P.T. Barnum, apparently. Good story, Paul.