Clash of the Gardeners

In the 1970s Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium nourished a hypercompetitive friendship and the biggest tomatoes in sports.

A few months ago, we ran a tomato-centric baseball story and, honestly, assumed we’d cleared out that particular vault. But a few wonderful readers provided leads on other such stories and after some further investigation we can confidently report that baseball tomatoes are, at very least, a sub-genre. Our first tomato was an accident, but today’s tomatoes are art, the fruit—yes, fruit—of an enduring baseball friendship.

“Baseball fields don’t just happen. You need somebody who cares and knows what he’s doing.”

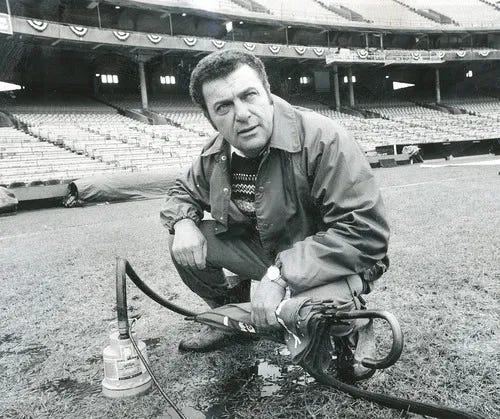

Pasquale “Pat” Santarone was in his office—the indoors one, under the left field stands. It was early April in Baltimore and the 49-year-old groundskeeper for Memorial Stadium was as glum as the weather. “We opened a week later last year,” he said. “This was a bad spring,” he said of 1979. “Snow up to our ass.”

Santarone had been in charge of the Baltimore Orioles’ home turf since 1969. He’d become renowned for both his craft and his competitive nature. In his hands, “caring for a ball field became a subversive art form.” He studied opposing players like an ambush predator and then did his best to literally rig the playing field against them. How the grass was cut or how hard the ground was depended on who’d be standing there. He once buried a wood plank under the batter’s box to stop the Twins’ Tony Oliva from indulging in his habit of digging a hole in the dirt with his foot. Santarone was particularly proud of what he’d once done to the A’s Bert Campaneris:

He always stepped in the grass between first base and the coaching box. I watered that spot real well before the game. Sure enough, Campaneris got a hit and swung wide. He went head over heels and the ball got back in time to tag him out.

Groundskeepers weren’t necessarily expected to be formidable, but this one was. He’d been known to utter dire threats to anyone who littered on his field, and the Orioles’ outfielders quickly learned how to replace any divots in the grass they made with their cleats. “I respect their profession,” Santarone said of the players, “and they better respect mine.”

As soon as football season ended in January, Santarone and his crew of 24 went to work restoring a natural grass surface torn to shreds under the churning feet of the Baltimore Colts. The first task of each new year was the installation of 37,000 square yards of a special variant of bluegrass sod. Next came the infield dirt, which was of his own recipe, a mix of sandy loam, clay, and soil. As the season approached the crew fine-tuned, building up the mound, measuring and measuring again, and ruthlessly hunting rogue pebbles.

He was credited with several innovations, including his design for a hand-made wooden rake for smoothing infield dirt. He invented a portable screen that could be rolled out to protect players in the field during batting practice. That was the one that got away: “I wish I’d gotten a patent on those. Now everybody in the league has them.”

“People think groundskeepers are just ditchdiggers,” he once said. ”I like to think of this job as an art form—a gardening art form.” If gardening was art, Santarone was its da Vinci, and every March and April a new masterpiece began life in his little left field office.

On a table across the room from his desk 10-15 small plants grew under fluorescent lights in a specially made bed of infield dirt and ground-up sod. A visitor moved to inspect them more closely. “Get away from those plants with that cigar,” Santarone snapped. “Nicotine knocks the hell out of them.”

The unwary smoker had come too close to Santarone’s second pride and joy. His office nursery was currently sheltering an essential part of Memorial Stadium’s character—and his own: a dozen tomato plants and a few pepper plants, bound for a one-of-a-kind baseball garden.

In the great tradition of baseball’s groundskeeping families, Pat began learning his trade at age seven, brought along to assist his father. Val Santarone was an immigrant from Italy who spent 27 years as the head groundskeeper at Dunn Field in Elmira, New York, home to the Double-A Pioneers. He gave Pat a push lawnmower and his first official job, and once child labor laws allowed he made his son Assistant Groundskeeper. Val died on the job in 1952, felled by a bee sting. Pat, 23, immediately took up the family business.

In 1962 the minor league managerial carousel brought Earl Weaver to Elmira. Weaver was an up-and-coming leader in Baltimore’s system, known for his short stature, competitive fire, and a tendency to occasionally carry off a disputed base after being ejected. In Elmira he became a fan of Santarone’s work, pronouncing him “as good as any groundskeeper in baseball,” and the two became good friends.

The groundskeeper also impressed Weaver with his extraordinary home garden, bursting with fresh produce from July to October, which he routinely gave away to the many cash-poor baseball transients passing through Dunn Field each season.

“I really like fresh vegetables,” Santarone said, later in his career, “and I like what I grow better than what I buy, so it’s just natural for me to grow them. And then it’s good for the peace of mind, too. Get out in the yard and nobody bothers you.”

The wonders emerging from Santarone’s garden sparked Earl Weaver’s imagination, and the prospect of a little peace of mind sounded good, too. In their three seasons together with the Pioneers, Santarone took the manager under his wing, teaching him the Way of the Trowel. “But I didn’t teach him all my secrets,” Santarone said. “That’s what makes him so grouchy—sitting up all night trying to figure out what I haven’t told him.”

In 1968, Weaver took over as manager of the Orioles, and a year later Santarone heard from Baltimore—he was being called up.

Baseball history is overstuffed with interesting dudes, but Pat Santarone is one to remember. He was a renowned groundskeeper, yes, but that was just his day-job. He made a little side money as a consultant for recreational landscape developers; one of his biggest clients was Pimlico Race Course, home to the Preakness Stakes, the second leg of thoroughbred horse racing’s Triple Crown. In his free time he kept a sprawling, Eden-like garden at his home in Phoenix, Maryland, growing vegetables, fruit trees, and roses. Even the greenest thumb couldn’t get good grapes to grow in the Chesapeake weather, so Santarone had those shipped in from California, but he took it from there, making his own wine.

When not growing prize-winning produce (he reported at least one blue ribbon at the Maryland State Fair—for tomatoes, of course), Santarone was a photographer with his own in-home darkroom. He scuba dived. He took regular trips to Europe. He was said to be an amateur mycologist and a darn fine cook. One of his favorite boasts, which he repeated like clockwork over the years, was his prize in a 1976 chicken-cooking contest in which his “Chicken Campania,” a dish he dubiously took credit for inventing, beat out 24 other entrants. Oh, and somewhere in all of this he raised seven kids.

At harvest time Santarone was known to give away a big portion of his garden crop. “People look forward to my little Italian care packages.” Lucky staff in the Orioles’ stadium offices could use these to chart the passage of the seasons, as midsummer strawberries turned to softball-sized tomatoes.

The groundskeeper waited a year, but in the afterglow of the Orioles’ 1970 World Series victory he decided to try something. In an awkward, fenced-off notch just beyond the end of the left field grandstand, he put down a few planter boxes and started growing tomatoes.

The plants benefited from regular sprinkler coverage and from the illumination provided by the massive bank of lights directly overhead, which were left on until midnight. From a tomato’s perspective, the ballpark garden was a pocket world with an open bar and a hundred impossible suns that kept the party going late into the night.

There were some drawbacks, of course. Santarone had to give the plants a special rinse after every ballgame, washing off spilled beer and soda from seats directly overhead. “I don’t want alcoholic tomatoes1,” he said.

Worse were the rifled foul balls that could prune an unlucky plant in half. Santarone didn’t mind when that happened, though; he liked the challenge of bringing the plant back to life, and invariably did.

Foul balls also made Santarone’s ballpark tomatoes (a proprietary hybrid strain of beefsteak varieties) famous, as they received more time on-camera and under discussion than any other vegetables in the country. By early fall you could hardly miss seeing them—the best specimens weighed as much as four pounds.

“I’ve gotten letters literally from people all over the world,” Santarone said. Many included requests for seeds. The plants became as much a part of the Memorial Stadium experience as the lawns and trees out beyond center field. “People come down and visit. When they come to the ballpark a lot of them will come down and see how the tomatoes are doing.”

Inspired by his grandparents and molded by Santarone, by the early 1970s Earl Weaver was a horticultural force in his own right. At his home in Perry Hall, a small suburban community northeast of Baltimore, Weaver managed a 600 square-foot garden, growing peppers, zucchinis, strawberries, and tomatoes.

Once growing season started Weaver would wake up early and make his way out to the garden for a few hours of planting. He’d come in for lunch, take a nap, and then make his way to the ballpark. Like Santarone, Weaver found something almost spiritual in the work.

“When you’re gardening,” he said in 1971, “you can think of anything or nothing. Mostly I think about baseball because the atmosphere helps put me in the right frame of mind. After a loss, gardening is especially good because then I’m chafing to get to the park so we can start winning again. After a win, I’m not so itchy.”

That year the hot new thing in the Weaver garden was eggplant, reportedly the size of footballs, but the tomatoes remained the star; 36 plants yielding dozens of tomatoes each. The Weavers couldn’t give the stuff away quick enough and they’d regularly can 40 quarts of tomatoes and just as much tomato sauce. Some of Weaver’s best were reported to be “as big as baseballs.” Impressive to most people, but not to Pat Santarone.

“I’ve always grown the biggest, juiciest, sweetest tomatoes. There’s no change.”

The Tomato Wars would ebb and surge over the course of the 1970s and early 1980s, featuring a rotating list of belligerents around Weaver and Santarone, the two great powers of the conflict. There were documented skirmishes as early as 1971, when a Baltimore Sun profile of “Weaver at Home” reported on the World Series-winning manager’s gardening prowess and competitive streak, saying, “he enjoys competing with Boog Powell, his first baseman, Harry Dalton, general manager, George Staller, coach, and Pat Santarone, groundskeeper at Memorial Stadium, to see who can grow the largest tomato.” Only in this particular ring would Boog Powell be considered a lightweight, but he was knocked out early and never came back for a rematch.

For his part, Santarone said he’d once battled another of baseball’s high-profile Italian gardeners, Billy Martin. Apparently Martin also grew tomatoes in Yankee Stadium and once brought some to compare to Santarone’s—but only once. “Mine were much bigger.”

The long-running contest drew national attention in the summer of 1979. The Orioles spent most of that season in first place, raising national interest in Baltimore’s cast of characters. Santarone’s profile would be further elevated by a waterlogged start to the World Series that October, when he ushered Bowie Kuhn around the swampy park, holding an umbrella over the commissioner and vowing to make the field playable in time for its date with national television, only a few hours away. One New York Daily News headline put the groundskeeper up for World Series MVP.

But Santarone made even more news with his tomatoes—and the way he trash-talked Earl Weaver with the brash ease of an older brother. “This is one game he knows he’s not going to win,” the groundskeeper said.

“I wouldn’t lower myself to lay claim to scrub tomatoes like that,” Weaver said of Santarone’s output. “They’re nothing much. I’ve got a lot better ones in my garden in Perry Hall.”

Fed up with hearing of the miracles Weaver was working in his home garden, Santarone had offered to make it interesting in 1979. He gave the manager room for four plants in the Memorial Stadium plot and—in a flash of bravado Satchel Paige would have admired—a three-week head start before the groundskeeper planted four vines of his own. The gardener with the largest tomatoes at the end of the season would win $25 and priceless bragging rights.

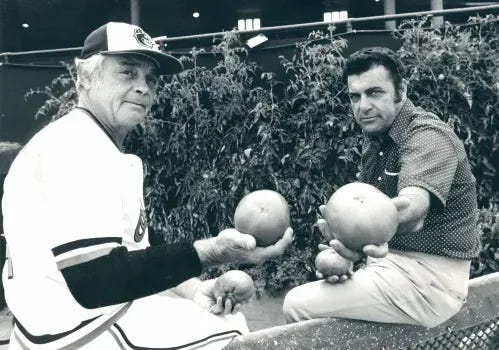

In August, a Baltimore Sun reporter named Isaac Rehert brought Weaver and Santarone together in front of the left field garden to check in on the hottest rivalry in sports.

Pat Santarone had the loose, boastful air of a man who knew he was up big. Weaver, in contrast, was described as “irate” and “contentious.” The groundskeeper gladly showed off some of his crop, still a work in progress, but even these looked to Rehert like “sure prize-winners.” Weaver just then did not have any results he was comfortable showing off. Santarone pounced.

“He’s never grown that big a tomato in his life. He wouldn’t know how.” The groundskeeper accused Weaver of using chlorinated water from his pool to water his tomatoes.

“That’s a rotten lie,” Weaver shot back. “The truth is that in weak moments I imagine this guy is my friend and I invite him to dinner and when I’m not looking he gets a bucket and draws water out of the pool and dumps it on the plants.”

Weaver held up one of Santarone’s finest. “Cut these open and you’ll see they’re not very good.” He accused his rival of crossing his tomatoes with a watermelon. “It makes them big as all heck, but they’re all pulpy inside. Mine are all juicy, like a good beefsteak.”

But the biggest story to break that day, one that received national attention, was on the subject of proper fertilization. Santarone was ready to reveal at least one of his secrets, a tactic few gardeners in America were in a position to steal.

“I’m a consultant for Pimlico Race Track,” he said. “I always get manure from the best horse that’s been racing there. This year my tomatoes are growing in manure from Spectacular Bid. Last year it was Secretariat. Do you know anybody else who just missed having Triple Crown manure in his garden?”

On May 19, 1979, Spectacular Bid, a battleship-grey three-year-old colt, handily won the Preakness Stakes to complete the second leg of his ongoing Triple Crown attempt. While everyone focused on the winner’s circle, Pat Santarone grabbed a bag and a shovel and made a beeline for the horse’s unoccupied stall, where he proceeded to help himself to some free memorabilia.

Spectacular Bid failed in his attempt to win the Triple Crown after a freak mishap prior to the Belmont Stakes (he stepped on an open safety pin) but the horse’s legacy continued in Memorial Stadium’s tomatoes2 (and, we suppose, in his hundreds of offspring).

Weaver knew he couldn’t top that one. His manure came from boring old cows. He stood up. “Look—I’ve gotta go play baseball.” The beaten manager wandered back toward the field, offering a parting shot as he went. “Ask [Santarone] about eggplant. Ask him every year who he has to come to for eggplant.”

Hearing Weaver allege that he, the winner of the 1976 Delmarva Chicken Cooking Contest, could not grow his own eggplant, Pat Santarone’s jaw dropped. “Why, that dirty…”

But, notably, he did not offer a denial.

When the competition ended in late September, Santarone’s tomatoes were reportedly so large they would not fit inside a baseball cap. Weaver’s tomatoes, on the other hand, were rumored to be so underwhelming that he had picked them and buried the evidence. Instead of a lopsided victory, Santarone won via forfeit.

It was a tough fall for Weaver. The Orioles lost a seven-game World Series to Willie Stargell, Dave Parker, and the rest of the Pittsburgh Family. His share of the World Series money more than covered the $25 he owed his longtime friend, but didn’t come close to recouping the loss in pride. When the results of the contest broke in October, the manager claimed foul play.

“I had some beautiful tomatoes growing,” he said. “But every time I would go away on a road trip Santarone would pinch the buds off my plants. I deliberately marked a couple of my buds one time before leaving town, but they never grew.”

Santarone wasn’t flustered by the accusations3. “I’ll say this for [Weaver], he’s a tenacious S.O.B. He hates to be beat, whether it’s baseball, golf, cards, or growing tomatoes. He’s a good manager at baseball. But everybody around here knows—just ask them—who grows the best tomatoes.”

Weaver never did beat Pat Santarone at gardening. But the joy was in the struggle. When the retired groundskeeper died in 2008 Weaver was asked to comment for a Baltimore Sun tribute. He went right back to the tomatoes, extending the feud that made Santarone so happy for one last round.

“He was there when I’d go out on the road,” Weaver said, “and I think there was a little tomfoolery. He might have been pinching off some of my buds.”

Alcoholic tomatoes are an actual thing and somebody please tell us the Orioles offer these at Camden Yards.

In the unlikely event that you were wondering, Santarone said that the most effective tomato fertilizer came from the 1971 Preakness winner, Cañonero II.

In April, 1979, the day Santarone displayed the tomato seedlings growing in his office, he admitted to the crime Weaver later accused him of committing. “I always win,” he’d said of their contests. “When the team is on the road, I tie a string around the stem of Earl’s plants and strangle them. I take the string out before he gets back and Earl always wonders why his plants haven’t grown.” He was joking—probably.

Entertaining story. Enjoyed it immensely.

Every ballpark should have a garden nearby with something growing.

Awesome article Paul. I remember Phil Rizzuto mentioning Weaver’s tomatoes when the Yanks were playing Baltimore one time. And I always liked Weaver & Sparky from Detroit - two great managers.

Far as manipulating the field goes, I wonder if that still exists. In my book that’s really cheating but so is ‘framing’ the ball but MLB allows that a well as ‘sliding’ gloves for the runners. Wouldn’t shock if you see the runners running with pool noodles next.

I think it was Abbot & Costello once saying, “I’m a diamond cutter.” When they were referring to running a mower for a baseball team.