Tomatoes in the Outfield

In 1975, Detroit kicked off an urban agricultural movement and the Tigers offered up a little bit of center field.

Hi Everybody—

Project 3.18 was on a go-go family vacation last week, beginning in the San Francisco/Oakland area and going as far south as we could on the Pacific Coast Highway before turning back due to landslide1.

The closest thing we got to a baseball attraction was a walk past the Joe DiMaggio Playground in San Francisco’s North Beach/Little Italy neighborhood. Apparently this is where Joe, Dom, and Vince DiMaggio, San Francisco natives all, played as children. It’s a lovely place, but if you want to play baseball you better hope no one is using the artificial turf kickball lot. That’s as close to ball as Joe DiMaggio Playground gets.

Now, this isn’t Project Family Travelogue, but we do have a little platform here and we’re going to stand on it and make one travel-related comment. Here we go:

Every hotel room should come furnished with the same number of towels as there are sleeping spots.

In hotel after hotel, our two-queen, sleeps-four rooms came stocked with just three towels. We see no possible efficiency to be gained by this strategy, even under capitalism.

There are a lot of serious problems in today’s world, and this sure isn’t one of them, but it does seem solvable.

Please. Give everyone a towel.

We didn’t have much time to write out on the road—too busy calling the front desk to ask for another towel—so our deep-dive into the forgotten history of the rawhide laces in the baseball glove will have to wait2, but we made enough time to write up a little morsel of a tale that we’ve been saving for the dog days of summer, which are certainly here.

No one knew when exactly it arrived, but by late June in 1975 it was five or six inches high and unmistakably a tomato plant.

The warm Michigan summer nourished the sprout and it grew happily. By the Fourth of July the plant was eight inches tall.

Tomatoes grew all over Detroit in 1975. Some in private garden beds in small yards of patios, and others on the empty lots that the city had turned over to citizen gardeners in a pioneering effort to fight urban decay. But this plant was special, because it was growing near the 440-foot marker in the deepest part of center field at Tiger Stadium.

It had grown through the gray gravel evenly spread along the wall to create a warning track for barreling outfielders. And as such it was unquestionably in-play, growing just a few inches inside the outfield wall.

Nothing on the turf at Tiger Stadium went unnoticed by the park’s head groundskeeper, Mike Fenell3. He said the plant had been growing there all through June.

But even Fenell couldn’t say where it had come from. “Maybe it just started to grow after some fan threw a tomato out there.”

Our research suggests tomato plants take around six weeks to grow eight inches tall. Working backward, the seed that produced the plant must have come to rest some time in mid- to late-May, where it went unnoticed in the gravel and was gently pushed into the ground by any one of the region’s late-spring rains.

But how did it come to center field in the first place? Was it originally a part of someone’s lunch, an errant bit of sandwich, lost in an exciting hand-waving, fist-pumping celebration? Or had someone in 1975 really emulated the behavior of prior generations by bringing a tomato to a public event with the express intent of throwing it at a performer?

We found no reports of vegetable-throwing at Tiger games in early 1975, not at the visitors and certainly not at the Tigers’ center fielder, Ron LeFlore, who had one of the better springs of anyone on the team.

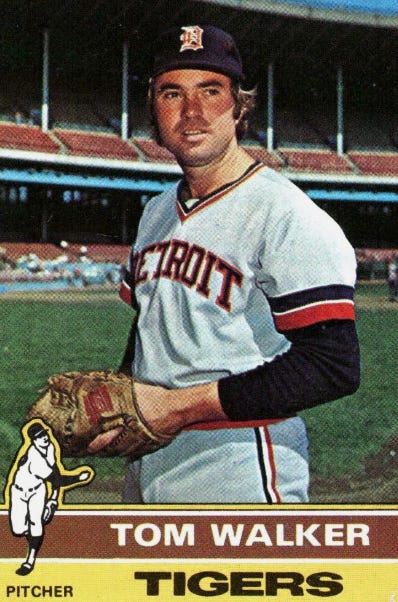

Fenell offered another theory, naming Tom Walker, a member of the Tigers’ bullpen. Fenell said Walker had “brought a few plants” to the ballpark. “But I don’t know if he put that one out there.”

Some pitchers have cutters, but Tom Walker apparently had cuttings. At first we thought maybe this was about marijuana plants, but there’s no way that would have been publicly traded knowledge in 1975, even if it was happening. It seems like Tom Walker just liked plants.

“I brought in some plants because somebody wanted some,” the pitcher said. “But I didn’t put [the tomato plant] out there.”

What plants did he bring, though? Who wanted them? Why is everyone so vague? Why is no one following up?

We don’t know what plants he brought or who had requested them, but it’s clear Walker had something of a green thumb, probably on his non-throwing hand. Made aware that a tomato was growing in center field, he frowned and grew concerned. “Somebody needs to give it some fertilizer.”

Fenell was way ahead of him. “I’m going to keep taking care of it.” The grounds crew were instructed to add the plant to their daily duties. First water the grass, then water the tomatoes.

By the end of July the plant was near a foot high. It had entered the local discourse and threatened to become a phenomenon.

“Have you noticed that since the tomato plant popped up the Tigers have been unbeatable?” one local resident asked in a letter to the Detroit Free Press’ sportswriter, George Puscas, whose regular “Love Letters” column encouraged this kind of whimsical discourse.

Maybe they should turn center field into a garden. This might help the Tigers go undefeated for the rest of the season; if not, they could always sell the produce.

The letter-writer was not overselling the alignment between the plant and the team. In early July, right around the time the plant became famous, the scuffling Tigers had ripped off a nine-game winning streak that no one thought they had in them. On July 10, the day of the ninth victory, the Tigers even managed to briefly vacate last place. A James and the Giant Peach-type scenario was on the table.

Turning forlorn spaces into gardens was all the rage in Detroit that summer. This was the second year of the “Farm-a-Lot” program that allowed residents to garden in city-owned vacant lots. The program had started with 35 lots in 1974, but 200 lots were given over to gardeners that summer. Behind walls of camouflage weeds and temporary fences, veritable crops of corn, tomatoes, squash, and kohlrabi were growing. Some gardens were 2,000 square feet.

The Farm-a-Lot program director was already thinking ahead to a loaner library of tools, using hydrant water to provide irrigation, and even bringing in gardening advisers paid for by a federal grant. Farm-a-Lot was clearly a success, as long as the money held, but could center field at Michigan and Trumbull really be considered unoccupied?

“Personally,” Puscas wrote, “I figure it is a bad idea for last-place teams to have tomatoes sitting loose around the stadium.“

After a two-week delay that was standard in the lost world where people communicated by writing letters to a newspaper, another Detroiter assured Puscas that tomatoes were the perfect crop for these Tigers.

I think you miss the point as do so many others. The reason the Tigers have that tomato plant in center field is so that, when the time is ripe…

…they will be able to play ketchup ball.

“Good grief,” Puscas said.

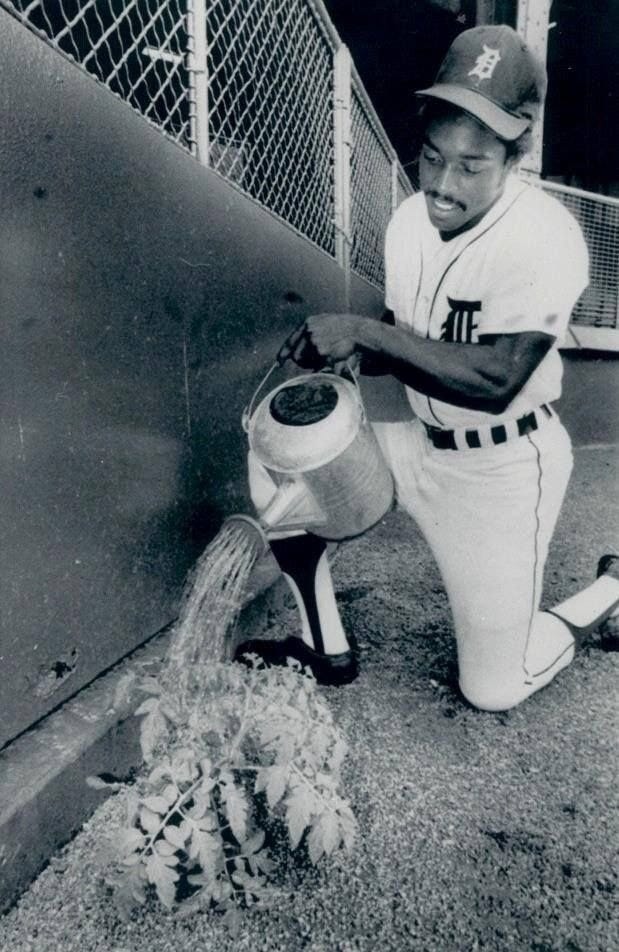

Ron LeFlore, the Tigers’ center fielder, did not mind the company out there. He helped water the plant when his schedule permitted, and a photo of him doing so is how we discovered this quietly wonderful little story. Presumably Tom Walker chipped in some fertilizer.

By this point in our research we were all-in on this little plant. How big would it get?

Would LeFlore reach down to pick up a rattling double and come up with a tomato by accident? Were the park’s ground rules updated in anticipation of this scenario?

Would the team make a special commemorative ketchup4 to be enjoyed by fans on Fan Appreciation Day?

Or, dared we hope, might the Tigers host one of the most winkingly irresponsible promotions in baseball history, hosting a “Free Tomato Day” for the center field bleacher fans?

We eagerly looked for the next report on its progress and the first fruiting, but August came and went without an update, and then it was September—harvest season.

On September 2, Joe Falls, the senior statesman of Detroit sports journalism, broke the bad news in his usual rough-grain prose, in a small and offhand line item titled “The Great Robbery.”

Is there not enough thievery in this town of ours? Who stole Ron LeFlore’s tomato plant from center field at Tiger Stadium?

Shame.

There was plenty of shame to go around at Tiger Stadium in 1975. That August the team endured a nineteen game losing streak that must have soured the ground under the field so badly that anything grown there would surely be inedible. Tomatoes should have been raining that summer, in which Detroit eventually lost 102 games.

Generally we are very happy working with non-fiction, but there are moments when the truth disappoints, and is definitely one of them. Robbed of Tomatoball and perhaps the Rally BLT, we should have at least gotten one of the finer moments in investigative sports journalism as the tomato thief was hunted down and sentenced to a stern talking-to, administered by Mike Fenell. Alas, there was no follow-up. The tomato plant disappeared as quietly as it arrived.

But in between arriving and disappearing, it was there.

We’ll be back next week with something a little more lively. Perhaps an ejection. But be warned: our first thought is to try and find something that involves produce, so we can make it three weeks in a row with a fruit or vegetable in our title.

A nice server in Big Sur told us that the NorCal equivalent of winter features late-year rains and related mudslides that disappear chunks of the PCH for years at a time. Really puts having to shovel our driveway into perspective.

The leather laces story is fake, but it sounds plausible for us, doesn’t it?

Mike Fenell—great groundskeeper name.

Do Detroiters/Michiganders say ketchup or catsup? Does anyone say catsup anymore?

The Mets in the early 70s had a sprawling tomato patch in their bullpen, just beyond the transparent part of the outfield wall.

Never, ever turn away a volunteer tomato. I’m going to blame that one on a bird depositing the seed.