In One Boat - Part 2 of 2

After a devastating regional flood, Cincinnati's expert groundskeeper battled the elements to bring the Reds' ballpark back to life.

This is the conclusion of a baseball story from the Great Ohio River Flood of 1937, a disaster that filled Cincinnati’s old Crosley Field with 20 feet of water. The flood prompted two curious Reds to return to the pitcher’s mound in a rowboat, where today’s piece picks up. Here’s the first part:

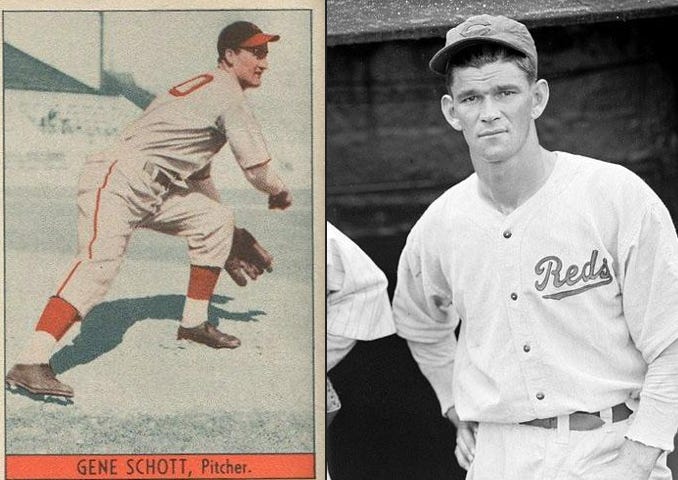

It would soon reach newspapers all over the country, but the photograph of Lee Grissom (waving) and Gene Schott first appeared in the Cincinnati Post, on January 27, 1937.

According to an accompanying caption, the two Reds “went hunting this week for the Crosley Field mound from which they are to pitch for the Reds next season.”

The words were written by the Post’s primary Reds correspondent, Tom Swope, who explained how the photo had come to be:

After they had obtained a boat on Findlay Street, quite a ways from the ball park, they rowed over the top of the centerfield fence, picked up Matty Schwab, superintendent of the park, and then rowed back over the diamond. They are not sure but believe they were 21 feet directly over the mound when this picture was taken.

Swope’s knowledge of the journey suggests he was a co-conspirator—a 1940 account says the idea for the shot “sprang from the imagination of a Cincinnati baseball writer”—but he was never placed directly at the scene. He was, at least, a booster, writing:

That stunt gave a lot of persons all over the country a better idea of what the flood really meant to Cincinnati than anything else that was published about the disaster or said about it over the radio.

Swope probably wasn’t at the scene, but we know groundskeeper Matty Schwab was—in another version of the photo, Schwab sits in the boat along with the players. There must have been a fourth person, behind the camera, and we wanted to find out who. Several weeks later, Swope finally ID’ed this baseball-history-famous photographer:

Grissom, manning the oars, merrily rowed himself, Schott, and Gabriel Paul, publicity director of the Reds, into the park before the flood had attained its peak.

Hey, it’s Gabe Paul—a general manager in four different decades and architect of the 1977 World Series Champion New York Yankees!

Everybody has to start somewhere, and in 1937, Paul, 28, was a protege of the Reds’ general manager, Warren Giles. As the club’s traveling secretary and press agent, Paul wrote “dispatches” (really press releases) that looked so much like actual news articles that many outlets just ran them as such. On January 27, he wrote about conditions at Crosley Field:

At the height of the flood the water covered all but six rows of the lower deck of the grand stand, and the depth at home plate was estimated at 20 feet. The left and center field fences were completely covered. Boats were able to go over their tops.

Paul was likely the chief architect of the players’ boat journey. According to Swope, a “baseball man” thought up the trip, “to get some national publicity out of the flood.” He may have been the photographer, too. “Because lack of pure water makes printing difficult,” he wrote to a Brooklyn sports editor, “we are unable to send you more than this one reduced-sized photo!”

Paul initially tried to stay out of the story, but he later acknowledged his role. “We met some guys on Freeman Avenue,” he told a journalist in 1980. “We borrowed a boat from them and we just started rowing.”

A three-block open-boat journey with an eccentric1 lefty apparently produced some tense moments. None of the men could swim, but Grissom appears to have tried to “dunk [Paul] over the side,” for fun. Later on, Paul “cried out in terror” when Grissom grabbed hold of some trolley power lines, hanging just a few feet above their heads.

”You’ll electrocute us!”

“Don’t worry,” Grissom said, “I know what I’m doing.”

The power to the trolley system had been shut off for several days. Did Grissom know that when he grabbed for the cables? There was just no telling with lefthanders.

“We made it to the stadium” Paul remembered, “and we rowed right over the center field scoreboard, went right over the top of it. I don’t know why we did it, I guess we thought it would be a cute thing to do.”

Whoever thought it up, the picture of Grissom and Schott floating in their office became a sensation. It had baseball, so Americans were automatically interested. Swope was right to think that a familiar landmark like a major league park would help people nationwide appreciate the awesome scope of the Ohio River disaster.

Opening in tragedy, the photo finished with joyful defiance. In a sad and sorry time, Grissom and Schott found a fun moment, but more importantly, they were on the offensive, setting a tone of revival and recovery. The bases might need buoys, but the two players’ presence on the diamond promised the city that there would be baseball again, one way or another.

The photograph launched a flotilla of imitators, and boats soon began arriving in the West End to make the passage over the ballpark. They entered over left field, rowed around the diamond as the players had, and exited via a low spot next to the right field bleachers. Some briefly tied up along the grandstand. There, one visitor with a piece of chalk wrote on a dry wall: “No Game Today. Wet Grounds.”

Disaster tourists soon became a citywide nuisance. With nothing better to do, they trooped down from dry areas to see the devastation up close. Matty Schwab and his grounds crew complained that the parade of boats through the park was pushing more oily waters toward the grandstand. The city emergency manager, Clarence Dykstra, solved the problem on January 31, declaring all flood zones citywide off limits to civilians unless he himself had signed their travel permit—and he didn’t sign many.

With the National Guard sealing off nearby streets and thoroughfares, the Reds could fully turn their attention cleaning up.

“We were lucky,” general manager Warren Giles recalled a few weeks later. “The water was back-up from the Mill Creek, and it had little current. Had there been a current, the damage unquestionably would have been serious.”

Giles said several dozen men patrolled the field in boats night and day. “They kept dragging the floating oil drums, whiskey casks, auto tires, timbers, packing cases, etc. away from the stands and clubhouse before they could do damage. Yes, I spent much time myself on the rowboat patrol.”

The slow current was enough to keep the grounds crew on their toes. On January 30, Matty Schwab “rushed to a boat and rowed frantically up the street,” chasing a ticket box office that had come loose from a temporary anchorage.

This kind of flood did have a downside: a fast-moving current might help clean up its own mess. A backwash would not.

As evident in the famous photo of Grissom and Schott, the water inside Crosley Field wasn’t just water, in the strictest chemical sense. The two pitchers floated in an “evil-smelling” toxic soup of Mill Creek water (filthy even in good times), untreated sewage, and petrochemical products.

In his January 27 “dispatch,” Gabe Paul explained the real trouble:

“When the waters recede, a coating of mud, slime, and debris will remain on the field.” But fear not, he assured anxious readers, “groundskeeper Matty Schwab is confident this will not prevent him from retaining the smooth playing surface the field has always had.”

The presence of oil meant that hosing down the ballpark would not be sufficient—the whole place had to be scrubbed and cleaned by hand.

The Reds were already estimating $35,000 in damage ($772,000 in 2025 dollars). The clubhouses at Crosley were located outside the park itself, beyond the third base grandstands, and they had been wrenched partially off their foundations by the floods. “It is doubtful,” Tom Swope wrote, “whether these buildings can be repaired satisfactorily.”

Swope documented the park’s rehabilitation with keen interest. He was a big admirer of Schwab’s work generally, this was surely the groundskeeper’s finest hour. “Matty promises that if the flood is not repeated in March or April, he will have everything spic and span by the time the Reds get home.”

Matty Schwab was “astounded” to find water in the press and office areas high above the diamond, leaving “a thick coat of goo, oil, and slime.” The groundskeeper, who reckoned he’d seen 20 floods in his time, declared this to be the “daddy” of them all.

By the end of January, the flood had officially become the worst water-disaster event in the nation’s history to that point. A record-breaking 13.5 inches of rain had fallen, resulting in an 18-day ordeal that took 330 lives and did $10-15 million in damage in Cincinnati and $400 million across the region. A million people were temporarily or permanently displaced from their homes.

Cincinnati limped along as the river slowly fell back. On January 31 it dropped to 74.8 feet and there was finally enough power to permit each household the use of one lightbulb and their electric radio.

By February, the river was in full retreat. 71 feet on February 1, 67 feet on February 2. Water service was restored the next day. On February 5, the Ohio fell back below flood stage for the first time in more than two weeks. Clarence Dykstra ended all flood-related restrictions and gave up his emergency powers.

Hundreds of people were hired by the Works Progress Administration and issued government brooms, tasked with sweeping debris into the water so the receding river would carry it away. At Crosley Field, Matty Schwab had also found a way to make the flood lend a hand.

As soon as the power came back on, the groundskeeper connected an electric pump to the network of drain hoses running under the playing area. Without running water, he pumped flood water from the field up into the stands to begin washing down the park’s infrastructure.

By February 8, Warren Giles was happy to deny reports that the Reds were shifting from baseball to water polo, saying “the diamond should come up for air in a few days.”

“The flood was no joking matter,” he said, “but I do not think it will have a harmful effect on the Reds’ baseball season. We already have sold more tickets for the opening day game than were sold at this time last season.”

All through the first week of February, baseball fans made their way to the Union Central Building, placing orders for tickets for the Reds’ home opener, scheduled for April 20. In the Post, Tom Swope declared Cincinnati to be “the nation’s No. 1 baseball town.” Where else would fans claim seats sitting under 10 feet of water?

On February 11, freezing weather arrived, transforming the field “to the finest skating rink you ever saw.” Two remaining feet of water iced over, covering all of the outfield and all but the top few inches of the pitcher’s mound.

In mid-February, Tom Swope reported that the damage to Crosley’s playing field was actually less than what had been inflicted by a weaker flood the year prior. Damage to the park structures was worse, however: “Some of the visiting players probably will be pleased to hear that the visiting clubhouse has been condemned.”

The remarkable Matty Schwab could find a silver lining in anything, and in this case, the upside was dirt:

Once the water is entirely gone, Schwab will let the mud dry enough to be raked up and carted off. Schwab was enthusiastic about this, which would leave him with “the greatest collection of top soil he ever has been able to assemble in his 22 years as superintendent.” He had already had some of the mud “analyzed” and found it rich in the sorts of fertilizers required to keep the grass green. He will let the soil cure for three years to kill weed seeds and let the oil degrade into less toxic forms.

Later in February, after the water-stained surfaces were cleaned and repainted, Swope added markings to the steel support columns, the center field flagpole, and the scoreboard, preserving the maximum height of the water inside the park for posterity.

Opening day has long been a tradition in Cincinnati. Acknowledging the 1869 Red Stockings, the first professional baseball team, the Reds opened every season at home, come hell or high water. In the 1930s, with fewer major team sports (and recreational activities generally) battling for attention, the return of baseball was a semi-religious event. Accordingly, many residents gave opening day tickets as Christmas gifts.

The tradition continued on Tuesday, April 20, 1937, when the Reds hosted the St. Louis Cardinals at Crosley Field. The Reds dressed in office spaces above the park and the Cardinals dressed in a repurposed storeroom, but the field was dry and playable.

By tradition, a group of die-hards stayed up all night waiting for the right field bleacher gates to open, and the seats of the “Sun Deck,” were packed by midday.

34,374 fans made it in to the 27,000 capacity ballpark before city officials ordered the ticket windows shut and barred. It was the third-largest opening crowd in the park’s history. “Plain and fancy, the carriage trade and the guys and gals from over the tracks, they jammed every nook and cranny of Crosley Field.”

Members of a fan organization, the Findlay Market Club, passed out flower arrangements to the Reds’ players. The manager, Chuck Dressen, received a large baseball made entirely out of white and red roses.

The fine day and happy occasion brought out the “color” in Lee Grissom, who demanded photographers take a picture of him standing on his head (we couldn’t find that one, unfortunately). He also snatched the band conductor’s cap and led the musicians in the “Organ Grinder’s Swing.”

After the game, Grissom married a waitress he’d met while trapped in Cincinnati during the flood. Lefties, you know?

The Reds debuted new attire: red satin jackets, white trousers, and black caps with red peaks. They looked modern and crisp and stood in stark contrast to the dusty, faded uniforms of the Gashouse Cardinals, whose jersey-material jackets made them look like the flood refugees.

Dizzy Dean had not become a Red that winter, but he had become the highest paid pitcher in the National League. Facing off against Roy “Peaches” Davis (guess where he was from?2), Dean was supremely confident before the game, in his usual cracked style. “Get me 12 runs,” he told his teammates, ”and I’ll sail through.”

For the first nine innings, the Cardinals got Dean zero runs, and just as he’d prophesied, he struggled mightily. The Reds logged 13 hits off Dean—but never the right ones, stranding 14 runners on base. Their pitcher, Davis, was better, and the game went into extras with a 0-0 score and both starters still working. Davis and the Reds lost in the 10th, beaten with back-to-back doubles.

The circumstances of the flood went unmentioned across every account of the game we could find. Either people in this time had short memories, or they just didn’t want to dwell in the past.

Regardless, a tough Reds loss was also an enormous victory for Cincinnati—and for Matty Schwab.

If anyone deserved a giant baseball made out of roses, it was Schwab. The Reds did name the new home clubhouse after him in 1947. He was able to enjoy that honor for a long time; Schwab retired in 1963 at age 83. He had been in his post for 60 years. His grandson, Mike Dolan, took over.

Cincinnati’s flood-prone Bottoms district was eventually torn down, making way for some big, hard-to-break public projects and stronger flood defenses. One early idea for the reclaimed land, emerging as early as the 1940s, was to build a new ballpark for the Reds. Riverfront Stadium opened there in 1970, secure behind a new network of flood control dams and protective walls that rose several dozen feet higher than the 1937 crest.

All the enhanced protections were made possible by the Flood Control Act of 1936, which gave the federal government primary responsibility for managing and preventing regional floods. A government-built Mill Creek control dam was completed in 1948. From that point on, the dugout at toilets at Crosley Field only went the one way, making a hardworking groundskeeper’s life just a little easier.

Next time: It’s spring training, so let’s do a spring training story. For anyone following MLB’s pilot of automatic balls and strikes this year (including some skepticism and even resistance among the rank-and-file), this 1971 story will play some familiar notes…but there will be more name-calling.

On March 17: “The Three-Ball Walk”

Left-handed pitchers were commonly held to be weird and unpredictable. Lee Grissom did his part to keep this stereotype alive.

Did you guess Georgia? Wrong! Peaches Davis was born in Texas and raised in Oklahoma. Even he wasn’t sure how he got his nickname—“Seems as how I must have eaten a lot of peaches at one sitting or something like that. Anyhow, [my brother] called me Peaches and Peaches I’ve been ever since.”

Davis didn’t sweat names very much. 50% of newspapers called him Ray, the other half went with Roy, but he seems to have remained neutral.

Great read as usual!

Cool stuff as usual Paul. Thanx! Loved Grissom was yanking on the trolley cables. Good thing some bimbo didn’t flip the switch accidentally!