Jackie Robinson’s Bad Bounce

On a stormy night in 1954, a baseball hero let his temper (and his bat) get away from him.

It all started with the weather. Bad weather is bad for good baseball, as one contemporary writer observed: “Poor visibility, slippery bats and balls, and mud underfoot all make the job more difficult. Tempers grow short and then the rhubarb1 sprouts.”

A garden of rhubarbs would grow at Milwaukee County Stadium on June 2, 1954, seeded by persistent rains that threatened to wipe out a much-anticipated clash between two National League rivals.

The Brooklyn Dodgers had been a perennial power in the league for a decade, and any contending team knew they’d have to get by Brooklyn on the way to the top. The Milwaukee Braves were making such a push in 1954, aided by some of unscrupulous local fans. During the first game in the series on June 1 a person or group of people seated in the outfield used hand mirrors to try and reflect the sun and dazzle Brooklyn’s hitters, prompting a police dragnet in the bleachers. The culprits were never caught, but the Dodgers squinted their way to a 2-0 victory.

A big crowd was expected for June 2, a Wednesday evening. The Braves’ owner, Lou Perini, could see the turnstiles spinning in his dreams, but when he woke up that morning the local weather report promised rain and threatened rain checks. Rain fell on and off all day long, but the conditions were (as assessed by Perini and the Braves) good enough to start the game on time. Barely.

The Dodgers immediately got to pitcher Lew Burdette, scoring a run in the first via a Jim Gilliam double and a Pee Wee Reese single. In the top of the second, it began raining in earnest. Brooklyn’s Don Newcombe struggled with his control in the wet conditions and issued a bases-loaded walk that tied the game. Burdette had similar problems, and the Dodgers managed their own bases-loaded walk in the top of the third. Now it really began to pour, and the umpires finally called for a delay.

The parties retreated under cover as the grounds crew rolled a tarpaulin onto the field. An hour passed, and the still-soaked players began to get impatient. One of the Brooklyn outfielders approached an umpire sheltering nearby.

“You’re not going to be able to play this,” the player said.

“We’ve got to wait,” said the umpire.

“But we’ve waited over an hour now. That outfield is like a soaked sponge.”

“We’ve got to wait a little longer.”

The home plate umpire, Lee Ballanfant, later admitted the weather had been “terrible,” producing results to match. “I wanted to let them play as far as they could.” As to why he wanted this, Ballanfant wouldn’t—or couldn’t—say.

73 minutes later, it was still raining when the game resumed. As the players tried to warm up, fans from the higher parts of the grandstands helped themselves to uncovered seats closer to the field, whose occupants had long ago fled. A local sports editor observed this migration and had the feeling that some in the crowd were “feeling no pain,” apparently having drank their way through the delay in relative comfort.

The crowd was pleased when the first two Braves’ batters hit doubles, tying the game, 2-2, in the bottom of the fourth. The Dodgers’ pitcher, Bob Milliken, was struggling, and he hit the pitcher, Burdette, putting runners at first and second.

This brought up the Braves’ shortstop, Johnny Logan. Logan had a 2-2 count when Milliken threw another ball. Ballanfant surprised everyone by calling it ball four.

The umpire insisted the count had been full, but that contradicted the information up on the scoreboard and the reckoning of the journalists present. To top it all off, the Dodgers employed a team statistician, a man named Allan Roth, who charted every pitch of each game. Roth also had the count at 2-2. But only Ballanfant’s vote counted, and he told Logan to take first base.

The Dodger bench erupted. Milliken ran in to argue and Brooklyn’s first-year manager, Walter Alston, joined him in front of the umpire’s face. “We were sure the count was 3-2,” Alston said. Infielders Gil Hodges and Pee Wee Reese joined, and so did Jackie Robinson, voicing his displeasure from all the way out in left field.

The Dodger bench mob howled and threw towels out onto foul territory in front of their dugout. The pain-free fans seated just behind them took the cue and began throwing paper cups, some still full of beer, into the visitors’ dugout. Brooklyn pitcher Russ Meyer reportedly arose and declared himself available for single combat. Several people in the crowd expressed interest.

Milwaukee police and uniformed ushers descended on the area and successfully kept the two sides apart. Meanwhile Walter Alston finished his remarks and the Dodgers’ rhubarb seemed to be withering.

The next batter, third baseman Eddie Mathews, hit a grand slam.

More shouting and more towels from the Dodger dugout. Ballanfant had reached his limit. Seeking some peace and quiet, he ordered the entire Dodger bench players to return to their clubhouse.

It rained harder in the fifth inning, the crucial frame under the rules of the time, which said that a suspended game would count only after five innings. The Dodgers’ lead-off hitter in the fifth was Jackie Robinson, and he was certain Brooklyn was about to lose.

“I didn’t think we had a chance of pulling [the game] out of the fire,” Robinson said later. He’d decided to go out on his own terms. As he walked up to the plate the left fielder gave Lee Ballanfant a few words he’d been saving up for the occasion.

“Lee, that is the worst decision I have ever seen; giving a man a walk on three balls.”

“Get in there and hit,” Ballanfant said.

“We’re going to lose a game just because you blew one.”

“Get in there and hit or I’ll throw you out.”

“You might as well. You’ve messed up the game as it is.”

The umpire obliged Robinson, who was ejected for the 14th time in his career.

At this point the details briefly diverge. How mad was Robinson as he trudged toward the dugout? He said not very, but a Wisconsin journalist seated near the dugout saw him “fuming.” According to that account, the still-riled fans nearby “really gave Robinson the business,” but the player himself said he wasn’t paying any attention to the fans.

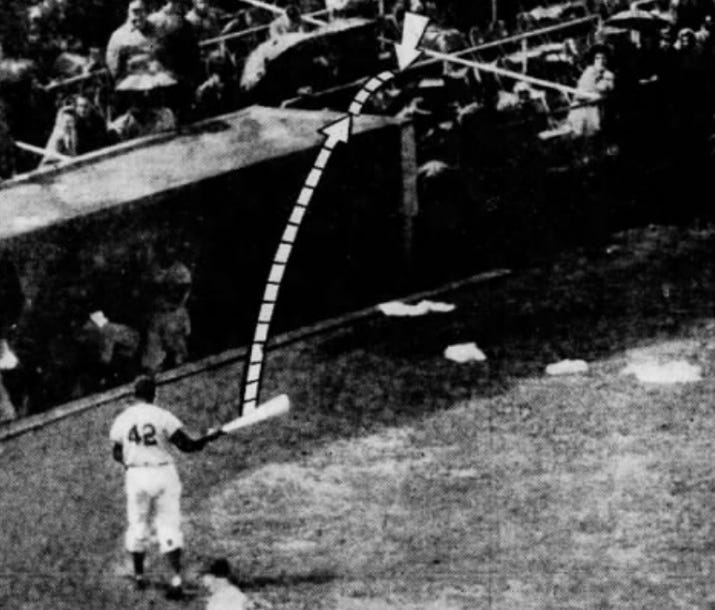

Everyone agreed on what happened next. Jackie Robinson suddenly threw his bat.

He said he’d intended to toss the bat back into the dugout, 20 feet away, aiming for a corner near the bat rack. “But I held it too long,” he said, “and it went too high.”

What he described as a “toss” others saw as a sidearm fling. The whirling bat rose over the concrete roof of the dugout and bounced off. It would have flown straight into the mass of fans leaning over the railing except for the presence of a uniformed usher, Harry Yelvington, trying to keep the crowd in its place.

The bat struck Yelvington on the head, but his uniform cap took most of the force. He lost the cap and his glasses and was left with a small bruise on his forehead. The bat spun away, making contact with a man and woman seated nearby.

Robinson was observed to “shrink in dismay.” He ran over to speak to Yelvington. “I apologized,” he said. “That was all I could do. I wouldn’t throw a bat into the grandstand. Hell, I’d be crazy to do that.”

Police spoke with the usher and the couple behind him. Yelvington, a Braves’ employee, was inclined to play proverbial ball. “I don’t think I’ll prosecute,” the usher said. “Robinson said he was sorry. I accepted his apology. I know he didn’t do it intentionally.”

And while the the couple behind Yelvington also declined to enter any charges against Robinson, the man reportedly told the police they planned to “file suit” over the incident. They soon left the park, still clutching the bat that Robinson certainly wished he could have back in more ways than one.

Dick Williams pinch-hit for the banished Robinson and the game continued in persistent rain. Williams hit a fly ball into left field, where it should have been an easy out for a 20-year-old rookie named Henry Aaron, but nothing came easy in these conditions. Aaron’s try for the ball missed and Williams ended up on second base. Gil Hodges singled him to third. Soaking wet, the Dodgers stalled, interrupting play and asking for towels to use to dry off their bats, still trying to end the game before it would count. They didn’t realize they were in the middle of a soggy, sloppy rally.

Another error. Another single. Another bases-loaded walk that chased Lew Burdette. His replacement fared no better and the Dodgers batted around. When Dick Williams grounded out to end the inning, Brooklyn was astonished to find they had scored five unearned runs and taken a 7-6 lead.

Now it was their turn to try and get three outs, and this they did, stranding the tying run at second base. The umpires called for yet another rain delay and made everyone wait another 33 minutes before officially calling the game at a quarter past midnight, sealing a highly improbable Dodger victory.

Six police officers accompanied the Dodgers’ bus back to their hotel in the early morning hours, but there was no further trouble for Robinson or his teammates. Everyone was too busy torching the Braves’ ownership for playing the game in the first place, and the umpires for letting it continue. The sports editor of the Milwaukee Journal was sure the two parties were in cahoots:

The umpires saved the ball club about $50,000 by letting the farce continue for the necessary five innings, but if that was baseball we’ll eat Lou Perini’s Borsalino2 fried in axle grease.

The June 3 conclusion to the series was washed out by Wisconsin’s summer monsoon, freeing one of baseball’s biggest stars to focus on damage control. Jackie Robinson said he was “ashamed” of himself and knew that the kind of behavior he’d engaged in was bad for baseball. “It was purely accidental and I hope people realize that.”

“The bat was wet and slipped out of my hand,” Robinson said. “I certainly had no idea of throwing it into the crowd. I flinched as soon as I saw where it was going. Then I told [the usher] I was sorry. I wasn’t even angry—just disgusted. I felt we had lost the game. I didn’t imagine we could come back with five runs in the next inning…”

In the grey light of day, the injured parties made ginger examinations of their respective skulls. Yelvington, the usher, still had a headache but said he intended to “forget the whole thing.”

The couple hit after the bat glanced off Yelvington were finally identified as “Mr. and Mrs. Peter Wolinsky3,” and it was clear that Robinson had more work to do with them. The Wolinskys had apparently found a lawyer, James Stern, even before they’d left the ballpark. Stern had been seated nearby and didn’t even have to chase down an ambulance to land this promising case. Mr. Wolinsky reportedly had a knot on his forehead while Mrs. Wolinsky remained in bed, suffering from dizzy spells. “I was stunned and shocked,” Mrs. Wolinsky said of the incident. “I didn’t know what hit me.”

Robinson arranged to call the Wolinskys at home and apologized. “He was very nice,” Mrs. Wolinsky said. She told a reporter that Robinson told her it was unintentional and said she accepted that. “The bat probably slipped.”

Stern, the lawyer, seemed an understanding sort, too. “I am not interested in seeing how much money I can collect from either Robinson or the Brooklyn club. My clients do not need money.” So long as they were medically cleared, the couple’s attorney thought the whole thing could be wrapped up with a public apology. “I’m sorry it was Robinson, who seems to be a nice fellow. I don’t blame him for getting upset.”

After all, Stern said, Johnny Logan had walked on ball three.

Digging into this story, we wondered what people at the time would make of Robinson’s short-sighted and damaging lapse in judgement. This was the man who promised Dodger executive Branch Rickey he could turn the other cheek when segregated baseball lashed out at him, who had then gone on to successfully turn cheek after cheek and turn the Great Experiment of integration into the Great Status Quo. What would people have to say when a blown call was all it took to get Jackie Robinson to do such a dumb thing?

The overwhelming majority of commenters we found accepted Robinson’s assertion that he’d never meant to throw the bat into the crowd, but many added hypocrisy to the indictment against him:

Jackie Robinson, the Brooklyn Dodger Negro star who claims he doesn’t want any trouble with anyone but usually manages to find it, staged another of his tantrums last night at Milwaukee County Stadium.

Some sidestepped Robinson’s legacy, preferring to focus on more basic aspects of his identity:

Robinson just had too damn much, but for a 35-year-old college-educated man who has been around, there was no excuse.

More than one writer pointed out that Robinson’s tendency to run hot had always been there, and had in fact been integral to both his selection as the first modern Black player and his success in that momentous role:

Baseball’s first Negro player since before the turn of the century had to be not only a great ballplayer, but a tough, pugnacious competitor. This was no spot for a gentle, retiring disposition.

There was general agreement that Robinson should be punished, and that his punishment should fit the crime:

It seems that a stiff fine and at least a week’s suspension ought to be in order to cool off this hot-headed Dodger.

Warren Giles, the National League’s president, was eager to cool things off, but from his view punishing a star was like throwing brush on an already raging fire. So hot was this blaze that reporters managed to track Giles down at his mother’s home in rural Illinois while he attended the funeral of a relative, asking what he was going to do about Robinson. No, this was not how Giles wanted to spend his summer.

On June 7 the league president sent Robinson a telegram informing the player he’d been fined $50 for arguing with Lee Ballanfant. In a separate statement, GIles explained there was no punishment for the bat-throwing “mishap,” declaring he was “convinced beyond doubt that there was no intent whatsoever on Robinson’s part to cause the bat to go into the stands.”

Or, as bone-dry columnist Red Smith put it:

Warren Giles has concluded that Jackie Robinson didn’t know the bat was loaded.

Robinson paid his fine and said, rather too assertively, that he “considered the bat incident closed.”

“Everybody knows it was an accident. I’m certain the people in Milwaukee know it was an accident.” He was off by three.

The Wolinskys reemerged in July. The couple had fired their original lawyer, James Stern, because (and this is a real quote) “he turned out to be a Dodger worshipper.” Stern had been replaced with new counsel, presumably a Braves fan.

The new attorney reported that Mr. Wolinsky had missed significant amounts of work due to recurring headaches, and Mrs. Peter Wolinsky had hardly gotten out of bed for several weeks. The couple was now looking for a “proper settlement.” In other words, a free bat wasn’t going to do it.

Stern, the secret Dodger worshipper, denied he’d been sacked. “I asked [the Wolinskys] if either of them was hurt, they said they weren’t, so I told them to count me out. I couldn’t see any point in pressing the matter if no harm was done.”

The 1954 season continued at a swifter pace than civil litigation ever could. Brooklyn finished in second place and Jackie Robinson had another productive year. Shuttling between left field and third base, he batted .311, but, at age 35, he was slowing down, playing the fewest games of his career and stealing only seven bases.

The lawsuit didn’t come until May 1955, arriving in the midst of one of the most exciting Dodger seasons in recent memory. When it came, the plaintiffs named Robinson and the Dodgers as defendants, seeking $40,000 in damages.

Robinson was served notice of the suit when the team arrived in Milwaukee for the first time. “I don’t know what their point is,” he said. “Maybe they’re trying to upset me to hurt our season.”

Hurting the Dodgers’ season was probably not the Wolinskys’ primary objective, but if it was, the ploy failed in historic fashion. At 36, Robinson wasn’t the central force he’d once been, but he and the Dodgers won the pennant and finally bested the New York Yankees, securing Brooklyn’s first World Series championship.

Brooklyn won another pennant in 1956 but Robinson’s batting average continued to drop, even as his advocacy for racial justice in baseball and elsewhere intensified. The combination became too much for the Dodgers’ owner, Walter O’Malley, who had dispensed with Branch Rickey in 1950 and preferred that his players stick to baseball. In the winter of 1956 the Dodgers traded Robinson to the New York Giants. He chose to retire instead.

Robinson announced his retirement on January 22, 1957. Two weeks later, February 5, the parties involved in the Wolinskys’ $40,000 lawsuit announced they’d settled out of court. The matter was finally resolved for a payment of $600.

It can be hard to find Jackie Robinson, the person, in Jackie Robinson, the legend, a civil rights pioneer who was also so good at baseball that he once stole home during the World Series. Today Robinson is mostly remembered via the baseball equivalent of a hagiography—tales of his discipline, talent, and courage. This particular story is not in that collection, but it serves to remind us that there was a real person in the middle of all those remarkable deeds, powered by a combination of strengths and failings.

The combative instinct that flared on June 2, 1954 wasn’t a virtue in the strictest sense, but without it, Jackie Robinson would have been somebody else.

The estimable Dickson Baseball Dictionary defines the “rhubarb” as “a noisy argument on the field of play,” often involving an umpire.

Borsalino, then and now, is a company that specializes in making luxury hats, so you know we had to get that quote in here.

This being a story from the 1950s, “Mrs. Peter Wolinsky” was never identified by her given name.

This was great!! Thanks Paul! I NEVER heard that story before. Thank you for the great in depth piece on it. And in '54 the Dodgers finally did "Wait till next year."

What a great read! Thanks for the story and the good writing.