Metsomania - Part 3 of 3

In which a group of very nice-looking young men perform a song from their album on The Ed Sullivan Show.

Welcome to the conclusion of “Metsomania: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment.” If you missed them, here are the other parts of our story:

Now that we’re finished, it’s a particularly great time to share this story with Mets fans—particularly those who were lucky enough to be around when the Art Shamsky was in action. Invite them to reach out to us to share their own stories and memories of the Mets’ first decade.

After the New York Mets clinched the Eastern division and cleaned off the strawberry yogurt, the team left town to finish the season on the road, a trip which fittingly concluded with a meaningless two-game visitation…er…series at Wrigley Field. Meanwhile, the organization busied itself learning a new task: preparing for postseason play.

In that process, the club announced that about 7,000 playoff tickets would be made available for purchase directly from the stadium box office on September 27. The line began to form immediately, several days prior to the beginning of the sale.

In the earliest hours of September 26, a group of a hundred or so people left the ticket line and broke into Shea Stadium. Inside, they picked at the damaged turf, snake-danced, and chanted “Shea belongs to the people!”

A solitary night watchman stood by as the kids commandeered bullpen carts and drove around the infield, shouting the favored slogan: “We’re No. 1!” at no one in particular. Some found hoses and staged a water fight. Still another group somehow managed to find and turn on the stadium lights and use the PA system.

“We couldn’t take it anymore, it was just too much being so near to the real thing,” one trespasser said to a reporter who somehow happened to be on the scene (our hypothesis is that the reporter was waiting in the same line for tickets).

This particular incident received little more than a blurb of coverage in the New York Times, written so matter-of-factly that it reads like satire. In a city wracked by Metsomania, it seems to have become broadly understood and accepted that happy fans celebrated with property crimes. The Times offered no explanation for how the trespassers managed to get in, how they were eventually removed from the stadium or what happened to them after. Absent these details, we can only assume they got back in line and bought their tickets.

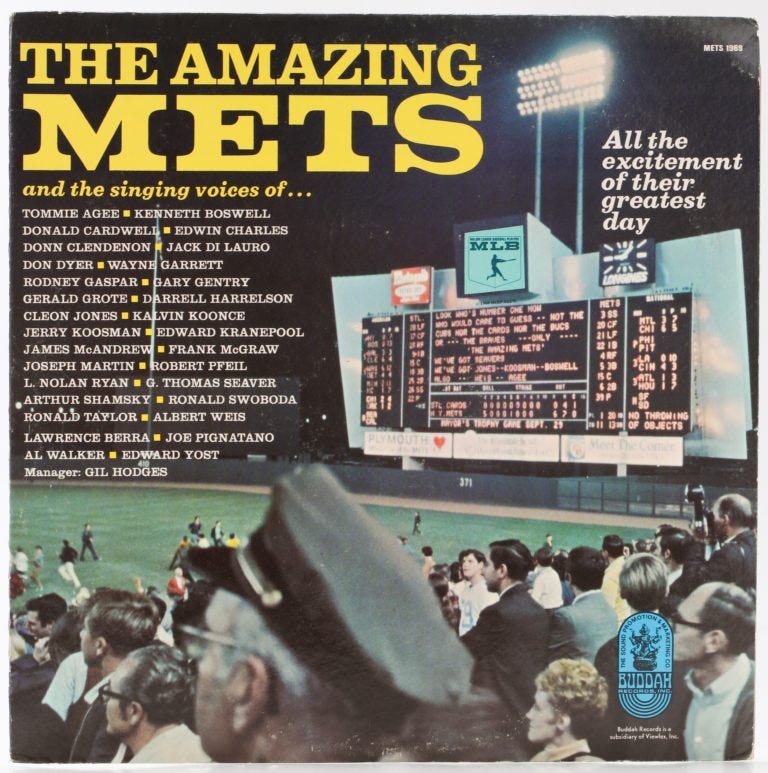

Actually, the Mets did one thing before they left town. On September 25, an off-day, the entire team recorded “The Amazing Mets,” a choral album of baseball-adjacent rah-rah that featured the players singing on top of canned band music. “It’s not bad,” said one of the crooners, right fielder Ron Swoboda, “if you’re sitting in a bar and have had a few drinks before you hear it.” Only the most afflicted Metsomaniacs could bear it, but the album nonetheless sold 50,000 copies.

In the National League’s first divisional playoff, the Mets faced the NL West champion Atlanta Braves. During the first two games in Atlanta, both teams combined to score 31 runs, but the Mets scored two-thirds of them and won both games. The offensive fireworks celebrated manager Gil Hodges’ triumph over the perceived limitations of his club. No one doubted the pitching, but many had doubted whether the Mets’ modest and motley collection of hitters could keep up. During the season Hodges proved a master compiler, fashioning solid hitters from platoon parts. In the playoffs he ensured that the Braves’ pitchers only saw New York’s offense from flattering angles. Under Hodges, as one well-read fan in Shea’s upper reaches observed, the Mets were “pure gestalt.”

The series returned to Shea Stadium for Game 3, and the Mets came from behind twice to sweep up their first pennant, carried by seven innings of relief pitching from the overpowering Nolan Ryan, who was having one of his Good Days at the perfect time.

25 men tried to repair the damage inflicted on Shea’s surface by the second crowd in as many weeks. “It wasn’t as bad as last time,” Groundskeeper McCarthy reported. “They got home plate and second base, but they couldn’t get the pitching slab.”

The celebration in the clubhouse was also tame in comparison to what had taken place on September 24. Mrs. Payson was at the ballpark, so this time the players kept their champagne corked and their trousers on until after she visited.

Over in the American League, the Baltimore Orioles swept their playoff against the Minnesota Twins. Baltimore’s rotation was arguably the best in baseball, anchored by the AL Cy Young-winning Mike Cuellar. Their pitching was backed by one of the era’s most formidable lineups, including Frank Robinson, Boog Powell, Davey Johnson, and Brooks Robinson. The club had no weak points worth mentioning. Anointed a “Team of the Decade” before their season even ended, the ‘69 Orioles were historically successful, winning 109 games to the Mets’ 100.

Pacing is essential to great comedy, and in drawing this Orioles behemoth, the beats of the Mets’ latest tragicomic gag became apparent. The Mets had gotten good just in time to get wrecked by one of the most dominant teams in modern history. This was new material, but the spirit was familiar.

Except that, for many New Yorkers, Metsomania had become a different condition in 1969, one that invited a different perspective. If you really thought about it, wouldn’t beating the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series be the most nonsensical, confounding thing the Mets could possibly do?

New York Daily News sportswriter Phil Pepe was badly ill with this evolved strain, so much so that it was impacting his work. On October 10, previewing the World Series, he gave Baltimore the edge over New York in eight of eleven aspects of the game. “The Mets and Orioles are a mismatch,” he concluded. “They do not belong on the same field.”

So informed, Pepe then made his prediction: “There’s no way the Mets can win—but they will. Say, five games. Why not?”

Game 1 went to the favorites, with Cuellar holding the Mets to one run while the vaunted Orioles lineup got the better of the Mets’ own Cy Young ace, Tom Seaver. But after that first game, the Mets’ pitchers seemed to have pilfered every bat from the Orioles’ dugout. During Games 2 through 4, Baltimore’s vaunted lineup managed just two runs.

The World Series came to Shea with Game 3. Rookie starter Gary Gentry pitched seven scoreless innings and Nolan Ryan earned a save. The Mets’ all-time undefeated-at-home streak went from one to two as they took a 2-1 Series lead. Tom Seaver pitched all 10 innings of Game 4 and gave New York time to win a weird, wild, walk-off.

Game 5 saw the Mets play their Greatest Hit: the journeyman first-baseman. Donn Clendenon was one of Hodges’ Platoon Gang: if lefties pitched, the 33-year-old veteran played. Otherwise, he sat, as he had throughout the entire playoff with the Braves. Clendenon finally got his turn against the Orioles’ left-handed starters and made the most of it. He hit three home runs in five games, a series record, capped by a two-run home run in Game 5, tying the score 3-3.

In the bottom of the eighth, the Mets took the lead on a pair of doubles from Cleon Jones and Ron Swoboda and added an insurance run from there. It was 5-3.

For seven years, the eternally-positive Mrs. Payson had promised every day that the winning would start “tomorrow.” But now it was the top of the ninth and the Mets were ahead. NBC’s cameras captured two fans holding a sign offering the Mets and their owner a new mantra: “THERE IS NO TOMORROW.”

Working on a complete game, Mets’ starter Jerry Koosman got around a leadoff walk to Frank Robinson and from there made two quick outs. “If they get one more here,” telecast announcer Curt Gowdy promised, “you’re going to see, probably one of the doggonest sights you’ve ever seen in sports.” Davey Johnson hit a fly into left field, where a beaming Cleon Jones squeezed the last out on one knee, completing the Mets’ reinvention. Formerly Amazin’, they were now, formally, Amazing.

Everyone then and everyone now knows what came next. The fans entered the field from every point along both sides and in the outfield, where people began scaling down the foul poles to ease a fifteen-foot drop to the playing area below. To avert disaster, the police quickly threw open every gate between the stands and the field, waving people through and shouting, “Four at a time!” over and over, giving the surging crowd somewhere to go.

Once safely out of the stands, the jubilant horde ripped the infield and outfield apart for a third, decisive time, stuffing grass chunks into lunch boxes, drinking cups, and pockets. One couple took so much turf that they fashioned it into hats and coats and beamed when a photographer took their picture.1 Fireworks and smoke bombs rattled off all over the park. 30 fans collapsed in hysteria and required medical treatment, more than the Beatles had laid out during their Shea appearance four years previously. Police had to wrestle home plate away from a sobbing teenager.

As she was leaving her seat after the game, a young boy came running up to Mrs. Payson holding a clump of sod, greeting the owner and offering her a chunk of his prize. Mrs. Payson later confessed that, not only did she accept, “I took it home and planted it in the middle of my lawn.”

The next day, the Daily News captioned an iconic shot of the smoking, seething playing surface with a message that provided both explanation and accommodation: “They believed in the Mets. Let ‘em have a field day.”

Safe in the clubhouse, some sadist put on “The Amazing Mets” album, though just as Ron Swoboda promised, it started sounding better as the champagne flowed.

VIPs made their way through in various states of shock. William Shea arrived, looking around in disbelief. “In my lifetime–they did it in my lifetime…” Just ten years after Shea had gone all the way for New York, his Mets had done the same.

Casey Stengel was everywhere. The old manager had retired in 1965 after breaking a hip (he fell off a bar stool at a celebration prior to the Mets’ Old Timers’ game), but Mrs. Payson kept him on the payroll in another position in which he had considerable experience: ceremonial vice president. Wearing his dark banker’s suit, the sage of this upside-down turned right-side-up world was the picture of delight as he roamed the chaotic locker room, sharing a glad if indiscernible word with everyone he encountered and otherwise shouting “A-mazin’” until he went hoarse. “This,” he said, after taking some time to gather his thoughts, “is the best thing that’s happened in the last five or six weeks.”

The mayor of New York, John Lindsay, was front-and-center, where he’d made a concerted effort to be since as far back as early September. When the Mets caught the Cubs, the mayor—up for re-election and facing some stiff headwinds—had practically stitched himself to Gil Hodges’ uniform, becoming the Mets’ Fan-in-Chief despite having no significant interest in or practical working knowledge of baseball. The story goes that when he attended baseball games, Lindsay brought an aide who would watch the game and discreetly let the mayor know when it was appropriate to get up and cheer.

“You can’t love the Mets and hate a Mets lover,” one political strategist noted. On November 9, Lindsay would be re-elected on the strength of a strong performance in Manhattan and, crucially, a better-than-expected showing in Queens.

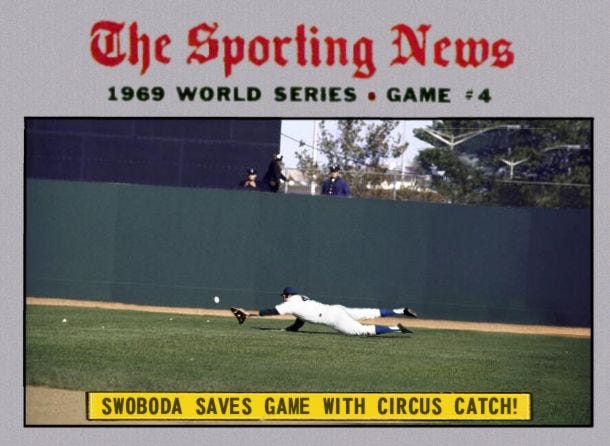

In the locker room, a reporter asked right fielder Ron Swoboda if the Mets had done something particular to earn the many blessings St. Jude bestowed upon them that season. “St. Jude?” the outfielder replied. “From now on, “WE’RE the patron saints of lost causes.” Swoboda, not necessarily known for his fielding, became one of the Mets’ chief apostles after making a no-return diving catch in right field that cut off an Orioles rally in Game 4.

“We weren’t supposed to do anything this year and we did it all,” Swoboda went on. “Nothing else will ever be as good as this. The only thing left for us to do is to go to the moon.”

Groundskeeper McCarthy made his last report of the baseball season: “[That celebration] was a lot worse than the other two times.” His crew would work 13-hour days trying to patch up the field before the upcoming New York Jets home opener, three days hence. The groundskeepers tried, but their efforts to quickly graft down new sod failed. They dyed the visible dirt green and hoped the Jets and Oilers wouldn’t notice.

For the players, life kept speeding up. The night after they won the World Series, the entire team sang on The Ed Sullivan Show. Before they went on air, someone had jokingly told Sullivan that one of the Mets’ rookie pitchers, Jack DiLauro, did a fair impression of him, and in front of the cameras, Sullivan asked to see it. DiLauro’s chortling mates obligingly shoved him out of the chorus line to stand next to the famous entertainer. He had not pitched in the Series and was out of baseball a year later, so doing his Ed Sullivan impression for Ed Sullivan may have been the most nail-biting moment of Jack DiLauro’s professional baseball career. Watching, one does not get the sense that Sullivan enjoyed the performance very much, but for those five seconds, DiLauro was the gutsiest player on the club.

(If you want to skip the singing—a choice we here at Project 3.18 might make ourselves—Jack DiLauro’s finest minute begins around the 2:10 mark)

The ticker tape parade was held the next day. The Mets’ open cars took the iconic ride through the city’s man-made canyons under a blizzard of man-made snow, stopping for three different rallies along the route. It was the third such parade of the year, after the Jets, who’d won the Super Bowl in January, and the returning Apollo 11 astronauts over in the summer. Those were grand affairs, but Mayor Lindsay had promised this one would be “the biggest celebration in the city’s history,” and it was, according to the Department of Sanitation, who had to clean it all up. Between four and eight million people attended the festivities.

At City Hall, New York’s City Council president accepted the Game 5 pitching rubber, signed by Seaver, Koosman, and Gentry: “To the greatest city with the greatest fans, from the greatest team.”

At another stop, an honorary “Gil Hodges Place” street sign was erected near the manager’s Brooklyn home. Despite the honor and adulation, the all-business Hodges remained on duty and vigilant. When Donn Clendenon skipped out on one of the rallies, his manager hit him with a $500 fine.

Still later on that endless day, the Mets were whisked off to a recording studio to bang out their follow-up Christmas album, which, mercifully, appears to have never been released.

On it went. The Dating Game. The Tonight Show (second time that year). Seven of the more prominent Mets booked a November show at Caesar’s Palace in Vegas. Many of the players canceled their winter plans to remain in New York and ride the wave of fame wherever and as far as it would take them. For DiLauro and the other young players like him who ended up playing only a few seasons, 1969 must have seemed like a year spent living inside a dream.

Back in September, a New York Times reporter profiling the rising Mets had listed off some of the many handmade signs that were a central part of the decor at Shea Stadium. She gave them in no particular order but inadvertently highlighted the clash of old and new underway at the park:

“To err is human, to forgive is a Met Fan,” one sign read. This was how it had always been, but some fans were already thinking about a different future: “One small step for Hodges, one giant leap for Met-kind.”

1969 showed millions afflicted with Metsomania that despite their condition, they could still root for a winner and live relatively normal baseball lives. After taking that leap with Gil Hodges, the old counterculture of failure fell apart, all mania for losing swept away with 1200 tons of ticker tape, toilet paper, and computer cards.

The Mets would remain in contention during the first half of the 1970s. During that era, attendance continued to crackle and the Shea crowds gleefully threw themselves into their new role: being the heavy…but that’s a Baseball Story for another time.

Between 1977 and 1983, the Mets again descended to their well-worn trench in the National League cellar, but this time the fans would have none of it. Attendance at Shea plunged. The ‘77 Mets drew a third of what the ‘69 club had. Going forward, New Yorkers would demand only competent baseball teams. In a city of winners, this was the most sensible approach.

That’s it for Project 3.18’s inaugural story! We hope you have enjoyed this visit with the Miracle Mets and their maniacal followers.

We came right out of the gate with a long-form piece, so let’s take a short breather.

In our next piece, a one-parter, we’ll (re)visit Cleveland in 1974 and illustrate just how readers and fans can play a role in telling wonderful stories with us here at Project 3.18.

Next: “Surprise Begonias”

And yes, Curt Gowdy, you were right. The picture of a couple wearing Shea Stadium is, probably, one of the doggonest sights I’ve seen in sports.

You’re overlooking the essential part of the Ed Sullivan clip: Frank McGraw’s belt buckle.

Oh my goodness I DID. The whole jacket is wild. I still can't accept the choice to use everybody's Christian name. Frank McGraw was Tug to his own family, but not to Ed Sullivan.

When I started this project, I had no idea it would become a vehicle for pointing out and critiquing mid-century fashion choices but I'd be lying if I said I'm not enjoying it.