Of Apples and Lemons

In 1938, the biggest innovation in baseball was all yellow.

On May 25, 1937, the career of one of baseball’s greatest catchers ended on a full count.

Batting in the fifth inning of a game at Yankee Stadium, the Detroit Tigers’ player-manager, Mickey Cochrane, worked a 3-2 count against the Yankees’ Bump Hadley, an affable pitcher with whom Cochrane was friendly. Hadley’s next offering was accidentally wild and inside. Cochrane froze. The ball struck him on his right temple and the lights went out and stayed out for ten days. When he woke up, the doctors told Cochrane he’d suffered a skull fracture and warned him to never risk playing again. He listened.

Mickey Cochrane was in his prime in 1937—maybe in anyone’s prime. A two-time MVP, a .320 lifetime hitter, a shoe-in for the soon-to-open Hall of Fame…felled by a fastball he didn’t see coming.

Cochrane’s beaning and forced retirement led to a serious conversation about requiring batters to wear helmets. And while there was some smoke, the idea ultimately failed to catch. Not even the most serious head injury since the death of Cleveland’s Ray Chapman in 1920 could get players to wear a hard hat.

In the wake of Cochrane’s injury a New Yorker named Frederick H. Rahr got to thinking.

A native of Massachusetts, Rahr was sometimes identified as “a Harvard man,” and he did apparently receive a Harvard degree—from the fine arts1 department—in 1929. In 1941 Rahr’s interests were given as “hunting dogs; hunting quail and pheasants; painting; golf; travel; and the theater.” Notice anything conspicuously absent from that list?

By 1936 Rahr was doing quite well for an arts major in the midst of the Great Depression. He was the sales promotions manager for a New York-based company, the Certain-teed Products Corporation, and his main job was to drum up consumer interest in home renovation projects that were then being subsidized by a New Deal piece of legislation called the National Housing Act. In other words, his job was to get people to spend on things like new roofs while the government paid part of the cost.

But since most homes already had roofs, Rahr had to get people interested in a new roof, and one of his big selling points was color.

“Color can stimulate us mentally, depress us in spirits, make us fighting mad, make us happier, or make us feel young or old,” he said. And a colorful roof would definitely make you happier.

After Mickey Cochrane was beaned, Certain-teed’s chief salesman updated his résumé. In 1938 Rahr described himself as a consultant and a “color engineer,” or a “color architect” in some accounts. He was sometimes identified as doctor or a professor (of what was never said) affiliated with Columbia University. Roofs were still a specialty, but he’d expanded into other domestic spheres including clothing and fashion, housewares, and the baseball.

In April 1938 Rahr announced he’d come up with an idea for stopping loss-of-visibility accidents in the national pastime, one that didn’t require players to armor their heads. He claimed that 80% of beanball victims later reported that they’d lost sight of the pitch that hit them and Rahr believed the ball’s visibility could be improved by making it yellow.

“Science has proved that you can see yellow farther and faster than any other color,” he said. Having completed what he characterized as an extensive testing process, Rahr was now satisfied that yellow was the optimal color for a baseball, “providing the greatest contrast to the white shirts of players, blue sky, and green grass on diamonds.” What’s more, Rahr believed a yellow ball could boost offense, improve umpire accuracy, and help fans see better, too.

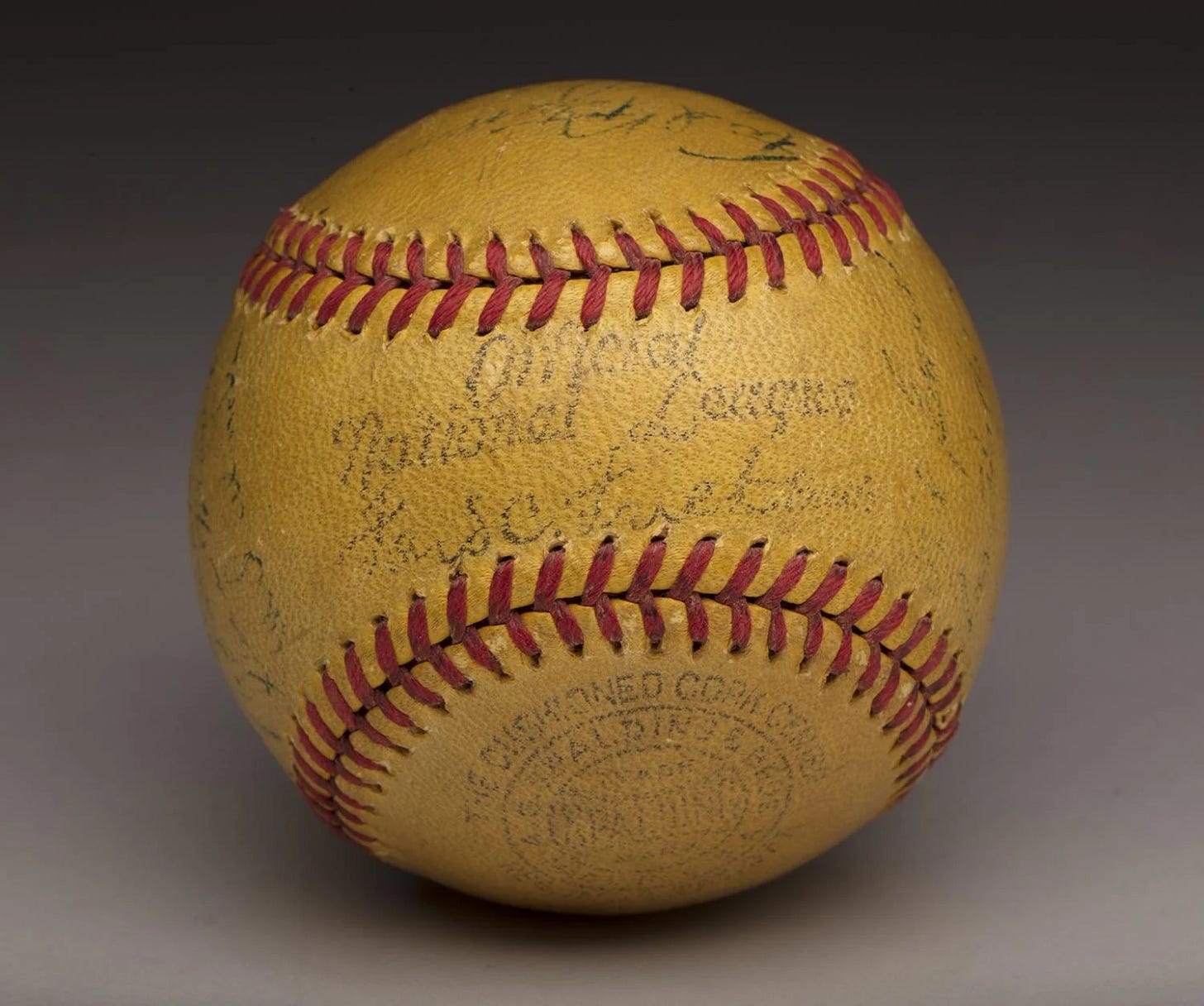

By the time he went public, Rahr had already made contact with Ford Frick, the president of the National League. Frick was interested enough to get Rahr into the Spalding facility that produced the National League’s balls. A special prototype line of Rahr-modified yellow baseballs was soon put into production.

“We’ve been playing baseball for 99 years with a ball of the wrong color,” Rahr said. “Let’s start the second century right.”

The baseball wasn’t always white. Early baseballs, home-made from horsehide leather, were often brown because that was the easiest color to get. There was some benefit to a dark color, however. Henry Chadwick, who set down some of the game’s first proper rules, recommended the baseball be dark red as late as 1875, feeling that a dark ball helped fielders tracking it through bright daytime skies.

The A.G. Spalding Company, which built an early monopoly on baseballs and other equipment, was still selling a red ball as late as 1891, but as ballparks became increasingly enclosed by dark-painted walls, a white ball became the standard.

It started white, at least. Over the course of a game the ball increasingly took on the color of dust and dirt, and batters sometimes struggled to pick it out, particularly in larger ballparks where people wearing white shirts and dresses in summer months sat in elevated seats ringing the playing area. Meanwhile pitchers threw harder and harder, and batters might have just two-fifths of a second to pick the mottled ball out of a mottled background after it left a fast pitcher’s hand.

After Ray Chapman’s death, new rules required a cleaner, whiter ball be used at all times, changes presumed to give an advantage to the batter. Many teams began leaving the sections of seats directly behind the pitcher empty, creating the “batter’s eye” area that is standard today—but in the 1930s those seats would still sometimes be sold as a last resort to meet demand. Sorry, batters.

In this historic march to a white ball, Frederick Rahr argued the sport had gone the wrong way. In no other field was white used to draw the eye’s attention. Yellow was the color of runway markings and construction signage for a reason.

Though he had somehow managed to get Frick’s support, Rahr knew that baseball’s owners were “some of toughest fellows in the world to sell.” He stressed that his yellow baseball was just that—a baseball dyed yellow, with no other changes to the ball’s liveliness, weight or stitching. But a ball that improved offense and helped umpires alarmed some of the powers-that-be, including the owner of the Washington Senators, Clark Griffith, who came out against the yellow ball as soon as its existence was announced:

What with Gehrig and DiMaggio, Greenberg and Gehringer, and a few other blokes, the pitchers are having a hard enough time now, without making it any easier for hitters.

Besides, Griffith said, helping umpires was never a good reason to do anything.

But Frick had allies, including the first-year president of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Larry MacPhail, who had something of a soft spot for hare-brained schemes.

Leland Stanford MacPhail was a baseball operator, innovator, and functional alcoholic. He got his start as one of the many disciples of the great Branch Rickey, who eventually recommended MacPhail to run the Cincinnati Reds (“he’s a bit of a wild man at times, but he’ll do the job”).

MacPhail helped put the struggling Reds back in the black and also pioneered night baseball in 1935, making Cincinnati the first major league team to play under the lights. But his hard-drinking ways soon turned off his bosses in Cincinnati and he left for the banking industry in 1936.

Meanwhile, the Brooklyn Dodgers were a mess on the field and nearing insolvency. Their primary creditor, the Brooklyn Trust Company, was desperate to install new leadership and Ford Frick recommended they talk to Larry MacPhail.

When he arrived in Brooklyn the Dodgers were $1.2 million in debt. Phone service to Ebbets Field had been shut off and the office waiting room was filled with bill-collectors and process servers. “I was handed about 17 summonses a week for quite a stretch,” MacPhail recalled. Half a million in debt to the Brooklyn Trust Company, he nonetheless took out another $200,000 loan to rehab the deteriorating park. He repainted the seats, built a free beer bar for the press, announced plans to pipe radio music into the bathrooms, resodded the grounds with turf from a Long Island polo field, and brought in the necessary equipment for night games.

MacPhail was expressive, flamboyant, and had a carrying voice akin to that of an adult moose. The executive’s outsized personality was a perfect fit in Brooklyn, where eccentricity was a core value. On mornings after tough Brooklyn losses, small crowds would gather on the sidewalks directly below his offices and listen in on his conversations three stories above them.

Larry MacPhail had a particular sensitivity to beanball incidents. During a game in 1940, one of the Dodgers’ stars, Joe Medwick, was hit in the head by a pitched ball. The team president surprised everyone by leaving the press box and wading through the grandstand with “a look of anguish” on his face, shouting that the beaning had been intentional. Making accusations like that, one of the umpires present described MacPhail as “coming down here to provoke a riot.” MacPhail was so convinced of foul play that he tried, unsuccessfully, to get a New York district attorney to press charges.

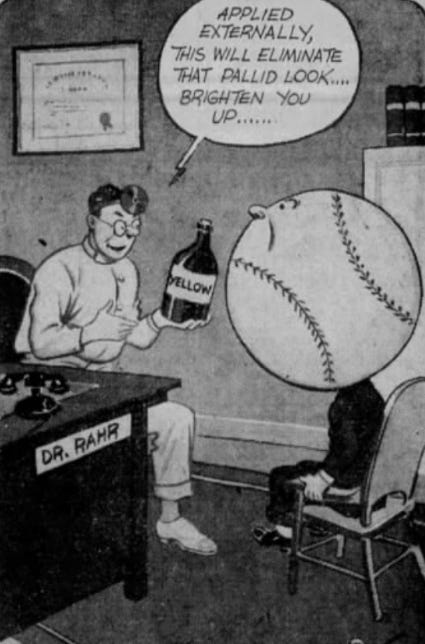

When Ford Frick needed someone to test out a new baseball that aimed to reduce beanballs and generate some extra fan interest, the perennially creative Dodger executive gladly volunteered. In the first game of a doubleheader against the St. Louis Cardinals on August 2, the “old apple” would become the new lemon.

Some of the yellow ball’s beta-testers possessed impressive credentials. The Dodgers’ manager, Burleigh Grimes, had a central role in the history of baseball (dis)coloration; Grimes had been baseball’s foremost spitball pitcher and the last player legally allowed to use the pitch.

Grimes said he liked the yellow ball, which he felt had been easier to follow from the bench. He thought it would help in places where there was no batter’s eye—or when greedy owners filled said eye with bleacherites in shirt-sleeves.

His counterpart, Frankie Frisch, at the helm of a sinking Cardinals ship, was pretty much up for anything2. “Oh, what the hell, try them out,” Frisch said. “The way my players are hitting nowadays, it doesn’t make any difference whether they use yellow balls, white balls, or red, white, and blue balls.”

From the Dodgers’ coaching box, an even more impressive authority weighed in.

That June, MacPhail had spent $15,000—an enormous sum—on a new coach for the Dodgers’ staff. His new hire was to periodically stand at first base, regularly pose for photographs wearing a Dodger uniform, and make provocative statements like “Brooklyn is the best baseball town in the world” in front of reporters.

The new guy’s name was Babe Ruth.

Ruth had retired from playing after 1937 and his only unfulfilled professional ambition was to manage a big-league team. Spurned by the Yankees and the Boston Braves, he was looking for any chance to show he could lead. Larry MacPhail made it clear this was not an audition for a future Dodgers’ managerial vacancy, but Ruth took the coaching job anyway. It sure paid3.

As a coach, Ruth encouraged the players, gave batting tips (solicited and otherwise), and sometimes took batting practice, giving New Yorkers one last chance to see him swing. Coach Babe was unimpressed with Rahr’s creation:

I didn’t even know it was yellow until somebody fouled one down there by me. The color don’t make no difference. It’s the guy who’s chucking them at you that counts. When a good pitcher is throwing that ball they all look like aspirin tablets.

The opinions of the active players varied and, tellingly, focused only on performance. Safety was not a consideration.

Joe Medwick, then the Cardinals’ left fielder and one of the game’s premier offensive players, was left lukewarm after hitting just a scratch single with the new ball. “It seemed sorta soft to me. It didn’t seem to have that hard clicking feeling that the white ball does.”

Leo Durocher, the Dodgers’ shortstop, “couldn’t find any fault” with the yellow ball, but there was a catch. “When you hit the way I do, they can throw a red ball, a green ball, or a fancy dress ball, even, and it doesn’t make any difference. I can miss any and all kinds.” Durocher, fondly dubbed “the All-American Out,” backed up his boast by going 0-for-3 with a walk.

St. Louis’ Johnny Mize clubbed the first yellow home run, turning it into a vanishingly rare souvenir for a bleacher fan. But Mize still wasn’t sold on using what he called “stitched lemons.”

No one spent more time handling lemons than Freddie Fitzsimmons, Brooklyn’s starting pitcher that day. The Cardinals made only three hits off Fitzsimmons, “whose saffron shoots acted like little suns, dazzling St. Louis’ batters,” according to one extravagant account. Fitzsimmons “went the route” that day, pitching a complete game, but afterward the front of his white jersey was streaked with yellow and his hands were stained.

“That dye started coming off all over my hands before the first inning was over,” he reported. “And as soon as the dye started coming off the ball got so slick I could hardly get hold of it.”

Larry MacPhail was satisfied by the yellow ball’s pilot performance in the 6-2 Dodger victory. He was so convinced of the blow he’d struck for progress that he had one of the game balls mounted for display in his office.

In the spring of 1939, Frederick Rahr stumped for his creation, though, lacking a groundswell of supportive players, he had rebranded. The yellow ball was now for the fans. Fans like him.

“Rahr is a baseball fan,” one 1939 profile asserted.

He’s near-sighted. He has trouble keeping his eye on the ball. He says the yellow baseball will help thousands of fans with poor vision and thereby help club owners with increasing attendance. To hear Mr. Rahr, it should be a unanimous choice.

If the sport wouldn’t go for the most visible color, Rahr told influential writer Grantland Rice, “then let’s have black or green baseballs with lots of deception. Why do this thing halfway?”

His pointed question begged another question: what was in it for Rahr, an avid quail hunter who may or may not have even liked baseball?

Money is the obvious guess. One period report put the number of baseballs in circulation across America at 7.2 million. If the majors changed colors the rest were sure to follow. But Rahr’s financial stake in that great yellowing is unclear. He doesn’t seem to have sought a patent for a yellow ball (you’ll be glad to know simply taking a thing and dying it another color does not constitute an invention) and we found no records showing he’d applied to protect anything, not even a proprietary mix of chemicals.

Rahr certainly seemed to imagine a rainbow-hued empire of sporting equipment. He talked about using colored sticks to help hockey players identify one another and a new color scheme for football uniforms.

But the baseball, his “gilt-edged pellet,” would determine the success or failure of the whole venture, and though the ball got more tryouts in 1939, it still wasn’t catching.

On July 23, 1939 the Cardinals and Dodgers tried again, and this time the Cardinals won overwhelmingly, using a yellow ball to inflict a 12-0 thrashing. Rahr, watching from the press box, had no explanation for how the ball’s offense-boosting power had seemed to miss one team entirely. In a second game that day the teams used a white ball but the result was the same: a lopsided 8-2 Cardinals win.

Opinions continued to vary along with outcomes. St. Louis’ Johnny Mize (4-for-5, plus that home run in the 1938 tryout) was now a true believer: “I can see the yellow ball much better than the white one.”

But Joe Medwick (1-for-5) jeered when he saw a Brooklyn official holding a box of “Rahrfied” balls between games. “You can keep those yellow ones!”

The teams tried again in St. Louis a week later, but the results on June 30 offered no insight. Hits and errors ended up comparable regardless of the ball used.

Even the once-fiery MacPhail was starting to cool on the yellow ball. Having pushed hard for the ball at the winter meetings, he now said its adoption should be driven by the players, who were driving in all different directions.

The next attempt came in a game between two previously uninvolved teams, the Philadelphia Phillies and the Boston Bees. They used the yellow ball in the second game of a September 3 doubleheader (related coverage described Rahr as a “doctor).” The game produced yet another set of unremarkable results and few strong opinions either way.

On September 17, the yellow ball took its final bow, fittingly at Wrigley Field, where many had thought it would be particularly helpful. Brooklyn won both games, and no assessments of the ball’s performance even made it into the record. The Dodgers never used one again and neither did anyone else.

Larry MacPhail would later say he hadn’t given up on the yellow ball, but his primary job was building a competitive Brooklyn team, a task at which he was succeeding. As the Dodgers increasingly raced for pennants, MacPhail wouldn’t risk embracing an innovation which might become a scapegoat.

Contention made the normally daring MacPhail sound downright pragmatic, a shift which illustrates the enormous difficulty innovating in any competitive space. The have-nots may be willing to shake things up, but the haves are determined to stick to what’s working.

By 1941 the yellow ball was mostly reduced to a stunt, the sort of thing independent teams broke out to sell a few extra tickets. A national semipro conference was still high on it, but this was a loose conglomeration of whackos who also favored giving two bases for an intentional walk and, most absurdly, using a “10-man” lineup in which a different batter would hit for the pitcher. As we said—whackos.

Rahr knew his window of opportunity had closed. In February 1941 he gave a “one-minute” interview to the New York Daily News, referencing a string of recent Dodger injuries and sounding like a scold:

Baseball has gone to sleep on the yellow ball for safety’s sake—bad! Why don’t you try to get them to go all the way this year? Reese, Medwick, and Case could have kept the Dodgers in the pennant race but baseball’s traditional “hard to see” white ball kept them in the hospital.

He continued as a color guru, “planning colors and color schemes for shingles, floor coverings, and everything in between for business firms.” World War II gave him opportunities to explain how camouflage worked, and he helpfully recommended war-worried homeowners distract themselves with renovation projects. His recipe for an emotionally restorative home: “a roof with blue-green shingles; interior walls painted pale coral, and a red-orange front door.”

Rahr’s prominence diminished with that of his baseball, and we’re not sure what happened to him after 1941. But whatever else he did in his life and no matter how many roofs he ultimately sold, at least one of his creations is now among the collection in the Hall of Fame:

But Rahr’s color revolution may have had one other victory—one so significant you have probably benefited from it many times. In 1941 the owners of Shibe Park in Philadelphia used Rahr’s favorite color on another high-visibility object:

“The foul poles at Shibe are now painted yellow,” the Brooklyn Eagle reported that May, “and are much more clearly visible than those elsewhere.”

As a proud MFA holder, we’re not knocking, we’re just saying.

After the game, Frisch remarked that the yellow ball “smells on rye bread,” and we think that’s criticism?

In 2025 dollars, Babe Ruth was making $340,000 to work June, July, August, and September.

I had no idea about this. I love learning about weird movements in baseball.

Whether Dr. Rahr was a color analyst or architect, it seems he was ultimately color blind about the concept of a yellow ball. Baseball players are a superstitious lot, so I imagine some might have liked a yellow ball if they were winning. To me, it would have been a deal breaker when it was discovered the yellow balls were not colorfast. Eeesh, who wants yellow hands, not to mention what it did to the palm of the glove. (Yes, I am OCD. ☺️) How long after the tragic Chapman incident in 1920 did batting helmets get adopted? And how much after that did the helmets have the attached ear/jaw protection? This was a fascinating read, Paul. Glad I neglected my work to read it.