On Ejections: You Have to Tip Your Cap

How have three different players gotten thrown out for giving respect?

Like most people, we enjoy the occasional perusal of a spreadsheet listing all major league ejections since 1889, and we thought this would be a good week to dip in. After writing about robberies and strikes and floods, looking into petty interpersonal nonsense can feel downright restorative.

We also like looking for patterns in the data, the stranger the better, and this time we noticed that three players have been ejected from a game for the same unlikely offense: tipping their cap. Not for throwing it, not for using it as a weapon; three players have been ejected for raising the brim of their cap slightly up off their head using two fingers, a traditional gesture of respect.

How did three different people get thrown out for doing this? Could sarcasm have played a role? Let’s find out.

1943: Buzz Off

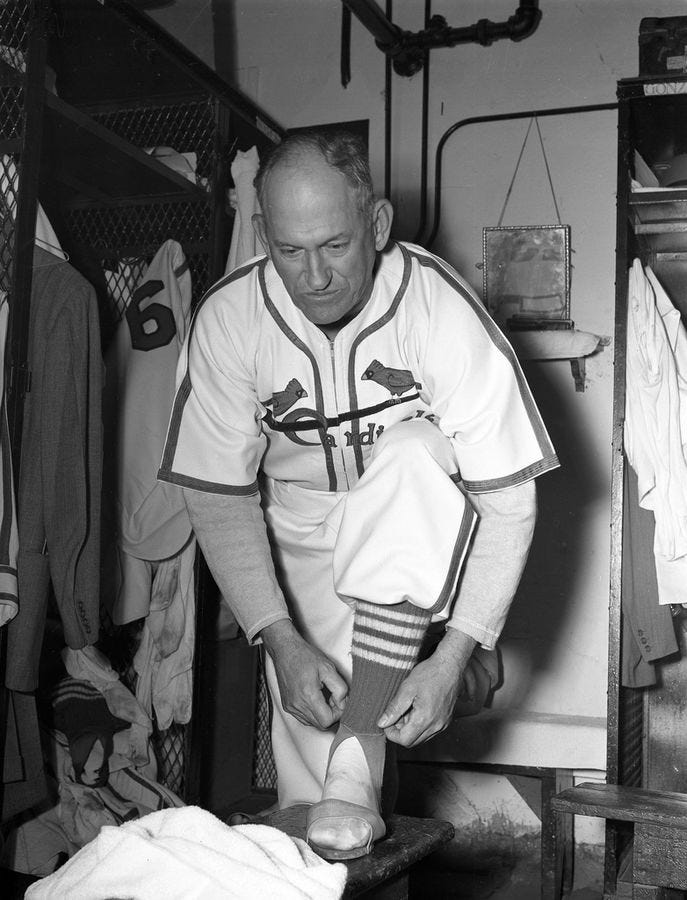

The first player to get tossed for tipping his cap was actually a former player and present coach of the St. Louis Cardinals. His name was Clyde Wares, but everyone called him Buzzy.

First hired by St. Louis general manager Branch Rickey in 1930, Wares was an institution, coaching for eight different Cardinal managers over 23 seasons. He was a mild-mannered man on a series of teams known for big personalities and flamboyant play, and he retired with more rings than LeBron James. He got two of these during World War II, an era in which the Cardinals were a National League power, winning two World Series and losing the other. In July of 1943 St. Louis was three games ahead of the Brooklyn Dodgers, their perennial rival at the time.

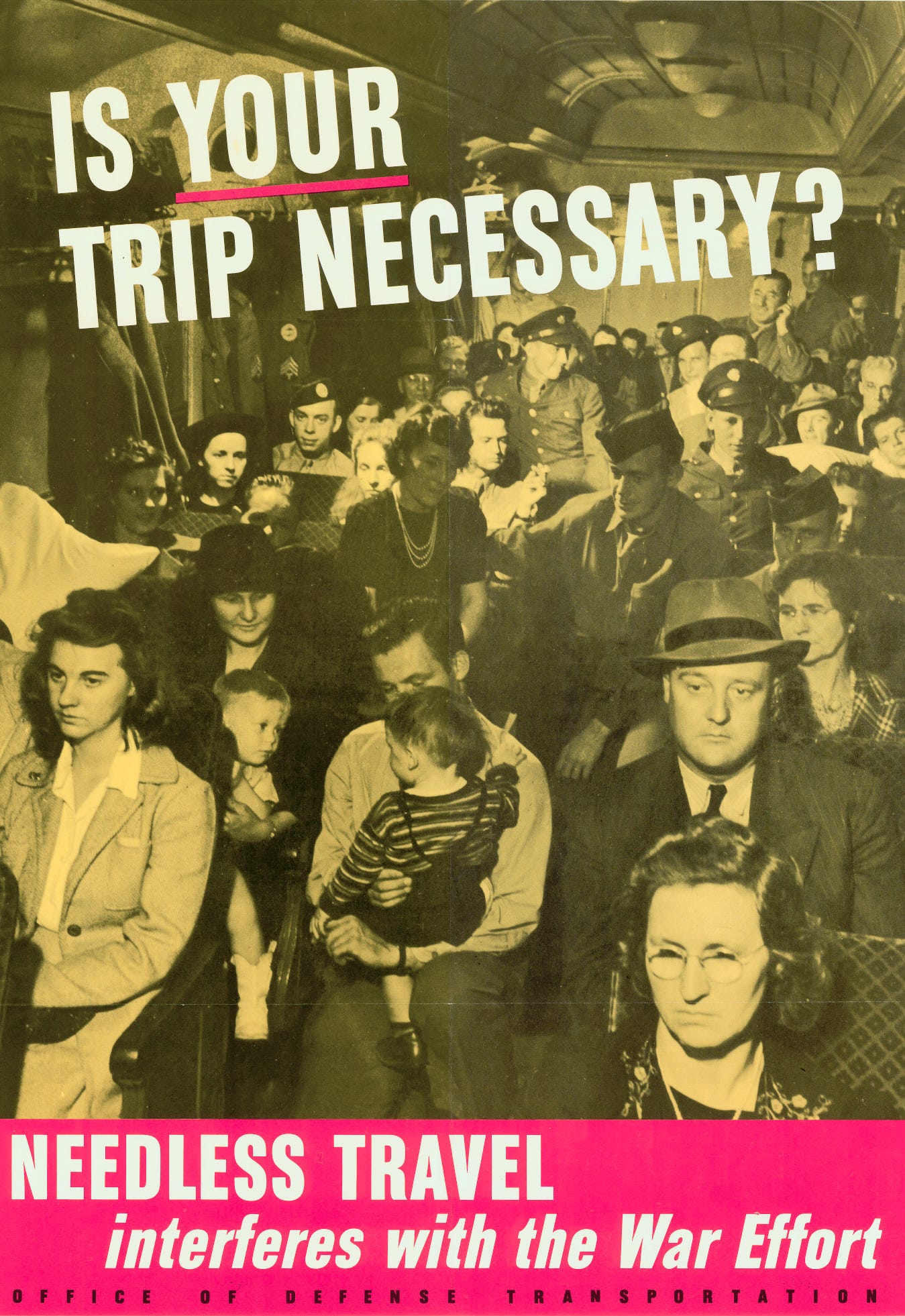

July 18, 1943 was the last day of a long road trip for the Cardinals, and that meant something different in World War II than it does today. Wartime travel restrictions required teams to change the way they scheduled games, and rather than returning home every two weeks or so, clubs spent up to four weeks’ time on the road, limiting their drain on precious domestic rail capacity.

Before the war, major league baseball players were the kings of the rails, traveling in luxurious Pullman cars and making their own timetables, but the needs of the military and related industry had moved them—and all other nonessential travelers—to the back of the line.

The Cardinals had been on the road since June 21, hitting every NL team on a tour now wrapping up at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. Even by wartime standards this was one of the longest road trips by any team, and everyone was understandably a little worn out.

This final series was particularly brutal for the Cardinals as it also included two games from an earlier visit that had been postponed due to rain. Wartime series were usually longer to begin with, four games being the norm, so before they could go home the Cardinals would have to play six games in four days.

The series turned out to be a rare speedbump for the 105-win Cardinals, who lost the first four games, the only time all season they lost that many in a row. Sunday July 18 was therefore the ultimate Getaway Day for the club, with just one doubleheader remaining to try and salvage something before they could at last go home.

A Sunday doubleheader was even trickier in Pennsylvania. Regular readers will recall that the state’s blue laws placed strict limits on when games could be held; only in 1933 did the state begin permitting baseball games in a limited afternoon window (after morning church and before evening church, the thinking went). Both games had to be completed by 7:00 PM.

The Cardinals won the first game, which was notable only for the team’s battery. The Cardinals’ wartime ace Mort Cooper threw nine innings of shaky ball and all of them were caught by his brother, Walker. Of the 13 sets of brothers to play big league pitch-and-catch during the modern era, the Coopers were one of the most accomplished, working both All-Star games and World Series games together. The Coopers helped the Cardinals break the team’s losing streak with a 7-4 win, but the sun was beginning to hang heavy in the west.

In the second game, Buzzy Wares did a very uncharacteristic thing.

The trouble started when the Cardinals’ pitcher, Murry Dickson, batted in the fourth inning. Dickson had been experimenting with a quick-pitch, and the umpire, Jocko Conlan, didn’t like it.

“If you don’t quit using that quick-pitching delivery, I’m going to call a ball each time you do,” Conlan told him.

Dickson had a ready retort: “Is that why you called three balls on the last batter?” This “sharp reply” apparently set Conlan off.

As Dickson and Conlan argued, the Cardinals on the bench began popping off in support of their pitcher, who eventually sacrificed a runner to second. As second baseman Lou Klein took his turn, the bench kept after Conlan, who heard “three players let loose a muted boo” in his direction.

The umpire spun toward the dugout, demanding to know who had made the offending noise. The players didn’t move, but their coach, Buzzy Wares, “widely regarded as a quiet sort,” looked right at Conlan and tipped his cap.

“You’re out!” Conlan barked. “Besides it’ll cost you $25, and I’ll make it stick.”

Wares rose and left the dugout without a word. On his way out to the clubhouse he walked right over home plate and just in front of Conlan’s nose. To protect his travel-weary players, Wares had literally taken one for the team.

The Cardinals were leading 6-5 in the seventh when bells sounded to announce the onset of curfew hours. To cut down on teams trying to manipulate games1 in an effort to gain a curfew-aided win, a new rule required that any game cut off in this way be completed during a future series. In this case, the final innings would have to wait until September 1, the next time the Cardinals visited Forbes. Two months later, Wares was required to spend those innings in the clubhouse, and, in true Buzzy fashion, he finished his sentence without complaint.

One More Thing:

The Pirates had joined several other clubs in posting a soldier and sailor to collect any stray baseballs donated by fans during games. Apparently it had become a popular practice to donate caught foul balls to local military training facilities, but fans often just passed their ball to anyone in uniform, and people gradually realized that few of these balls were ever making it to base.

Formalizing the donation process had helped ensure the gifted balls reached the army camps they were intended for—instead of ending up in somebody’s backyard.

1960: Oh, Brother

Of the three, the next cap-tip ejection is the weakest. We had almost crossed it off, until one last bit of poking around produced both the necessary proof…and an amazing coincidence.

This one took place on May 13, 1960, at Candlestick Park in San Francisco. The Giants’ new ballpark had first opened its doors on April 12, and everything was so fresh you could still smell paint. While nobody fully understood how the new park would play over the course of a season, it was already clear that folks coming out to Candlestick should wear a windbreaker over three shirts.

Almost 42,000 people paid to chill their extremities that night, and 1000 more were turned away. Everyone was eager to see a stellar pitching matchup, with Don Drysdale starting for the Dodgers and a hot pitcher named Mike McCormick starting for San Francisco. McCormick was starting the year off with real…ahem…buzz. The lefthander, just 21, had a 4-0 record, the best in the league. “McCormick,” one overeager writer said, “pitches as if ready for the Hall of Fame.” And Don Drysdale was pretty good, too.

McCormick would win again that night, pitching a shutout against the Dodgers and extending the Giants’ winning streak to seven.

Drysdale pitched very well, but got no run support. All it took to make him a loser was an Orlando Cepeda single in the fourth inning followed by an RBI double from Willie Mays.

Three innings later that was still the only run Drysdale had given up, but the Dodgers put two men on and he was lifted for a pinch-hitter (who struck out). Manager Walter Alston had been comfortable subbing Drysdale out of the game because he had one of the hottest relievers of that moment ready to replace him in Larry Sherry.

Sherry had come out of nowhere to help the Dodgers strangle the Go-Go White Sox in the 1959 World Series, and that performance set a high ceiling for him in 1960. He would pitch a career-best 142 innings out of the bullpen, being on the mound so much that he was the team’s pitcher of record 24 times, with 14 wins and 10 losses.

Sherry pitched a smooth seventh inning and got the first two batters of the eighth before he ran into trouble. The next two batters singled and doubled, and Sherry tried to escape facing Giants right fielder Willie Kirkland. He was determined to stay out of the middle of the strike zone, but umpire Augie Donatelli declined to call any of his edge-case sliders for strikes. With a 3-0 count, Sherry intentionally walked Kirkland but ended up facing pinch-hitting Willie McCovey, who singled in a run, as did the batter behind him.

That was the end for Sherry. Alston came out to get him before the deficit grew any larger.

Few experiences irritate a pitcher more than seeing an inning fall apart with two outs already in the bag, and Sherry decided to blame all his troubles on Donatelli’s stingy strike zone. As he walked past Donatelli on his way to the clubhouse, Sherry put a hand to his own throat and looked at the umpire, giving him the “choke” sign2.

Donatelli wasn’t going to take that, and he ran Sherry out of the game. An argument ensued, and none other than umpire Jocko Conlan had to come over and talk Sherry into leaving the field under his own power. As he finally departed, the pitcher tipped his cap to Donatelli.

So, there was a sarcastic cap-tip involved, but Sherry was already ejected when he did the deed. Still, it’s pretty weird that Conlan, the only umpire to ever be involved in a cap-tip ejection, 17 years prior, was also a part of the next one. But Conlan’s presence is only the second-best coincidence of this story.

The Dodgers’ primary catcher in 1960 was John Roseboro, but he had that night off. Instead, the team’s new backup, Norm Sherry, worked behind the plate. Norm Sherry was, you got it, Larry Sherry’s brother.

Just a week earlier, on May 7, 1960, the Sherrys had become the 13th and last sibling battery in modern baseball history.

We have about 70 Project 3.18 stories under our belt at this point, and we had never encountered a single brother-brother pitching tandem. Today, writing on an entirely unrelated subject, we ran into two.

1978: Four-letter Words

We’ve moved all the way up to 1978, safely within the Quotable Era once again. It never ceases to amaze us that for a period of several decades sports journalists just didn’t bother asking the athletes about their day.

History’s last cap-tip ejection didn’t feature any remarkable coincidences or a memorable sociopolitical backdrop, but it does involve another Cardinal, one of the better ones—Ted Simmons.

Simmons might have been the second-best catcher of the National League in the 1970s, and in 1978 he was one of the only good things going for the St. Louis club, which struggled to stay out of the basement of the NL East.

A switch-hitter who hit for a high average with decent power, Simmons was a four-time All-Star in his tenth year of big-league service. He was a talented, outspoken leader playing a crucial position, and as such he felt entitled to a little deference.

In a May 27 game against the Cubs at Busch Stadium, the Cardinals were down, 2-1, in the ninth inning when Simmons came up to bat and hit a 400-foot home run off the Cubs’ best reliever, Bruce Sutter, tying the game. It should have been a celebratory moment—especially because a St. Louis bakery had promised a free cake to any Cardinals’ player who scored a run last night—but the celebration ended abruptly as Simmons crossed home and was ejected by umpire Paul Runge.

The ejection ended Simmons’ outstanding night at the plate. He’d already hit a double, a triple, and a home run, and with the game now going into extra innings, he should have had at least one more chance to bat. Instead, that last at-bat went to backup catcher Tony Scott, who ended up making the final out in a game the Cardinals lost, 3-2. It was their 15th loss in 16 games.

It took a few days to get the whole story of what led to Simmons’ ejection. After the game Simmons insisted he was blameless. “You’ll have to ask Runge. He’ll tell you what happened.”

The umpire only did a little better, saying Simmons was ejected for “a gesture and a remark,” but when pressed he said Simmons hadn’t used profanity.

“Simmons didn’t cuss me,” Runge said. “When I talked to him earlier in the game I told him, jokingly, to not be so uptight. Something was working on him, it seemed to me.”

No profanity—that was a head-scratcher. When players were thrown out, the offending comments tended to be unprintable.

Now even some of the Cubs were sympathetic. Chicago manager Herman Franks felt it was a sad sign of the times. “I always thought as long as you didn’t swear you couldn’t get thrown out of a ball game. It ain’t so anymore. I got chased once last year for throwing up my hands in the dugout.”

Only the next day—presumably fortified by some delicious cake—did Simmons give his full side of the story to a St. Louis columnist:

I learned from the veteran [umpires] when I first came up, from Al Barlick and Chris Pelekoudas and Ed Sudol. And ever since [Runge] has been in the league, this guy has been trying to teach me all over again and I ain’t got the time. The other night we’re down, 2-1, in the ninth and Sutter throws a forkball for strike one. The next pitch is way inside, almost hits me, and Runge calls strike two. I turned around and looked right through his mask but I didn’t say anything. I hit the next pitch out but as I round second I see him staring right through me and as I round third he’s got his arms folded on his chest, glaring. So just as I get to the plate, I tip my cap to him. And I’m gone.

Now Runge had to respond, and he revealed what Simmons said to earn an early shower:

“He tipped his hat and said, ‘take that.’”

Take. That?

“He definitely showed me up,” Runge insisted. “It was a perfect opportunity for him, and he took the opportunity.”

The Cardinals protested the ejection. “The only job [Runge] had was to see if Simmons touched the plate,” manager Ken Boyer said. What if Simmons cap-tip had been intended for the cheering fans, he asked. How could a player “show up” an umpire if no one else could tell anything was happening? “I don’t think the average fan knew they were having words,” Boyer said. “Teddy never once turned around.”

Runge said he and Simmons had earlier words in the seventh inning over another pitch, and the slate between the two didn’t seem to have been particularly clean to start with. “I think this has been happening, or brewing, over a long period of time,” Boyer said. “But unless you call an umpire a name, you shouldn’t be kicked out.”

So here we have the “truest” ejection of the three. Buzzy Wares wanted to be thrown out; Larry Sherry was already thrown out; but Ted Simmons was ejected for a sarcastic cap-tip and saying, “Take that.” after hitting a home run.

Is this enough disrespect to provoke an umpire? Or did Runge overreact?

The next day the Cubs were ahead in the sixth inning when the game was paused by heavy rains. The umpires eventually gave up and called the truncated game, giving the Cubs the win. The rain stopped for good ten minutes later. The Cardinals protested that game, too. Boyer, the manager, said it couldn’t be helped:

“You seem to do more complaining when you’re losing.”

Next week we’re going to start a story that somehow manages to include fights, strikes, riots and one of the most remarkable lineups in baseball’s long history.

How do you find a story with all that? Just start with Ty Cobb. The rest takes care of itself.

On May 12: “Sandlot Corner”

Use blue laws to manipulate game outcomes? Who would do such a thing…?

One account referred to Sherry’s offending gesture as the “apple up,” but we couldn’t find any explanation for what that meant.

A tip of the cap to you, Paul, on an interesting piece. Here’s a link to a Rule of Three cap-centric column. . .

https://ruleofthree.substack.com/p/hats-off-to-you?utm_source=publication-search

Umps over reacting ‘ya think? I miss the old days of umps getting dirt kicked at them from Billy Martin. If I remember correctly (which hasn’t been done in a while) I think Earl Weaver did also. Then again they take it more personally… to them it’s an ‘F You’ message perhaps.

Why can’t we all just get a long.

Maybe every ball park needs to be playing ‘What the world needs now is love.’ Which brings me to a pet peeve of the Red Sox besides their common Yankee foe. But some other time for that.

Thanks Paul!! Loved it.