Sensible Send-offs

Ejection stories for each of the five senses.

Here at Project 3.18, we like to write about ejections, particularly if we organize them around a theme. We’ve written about rain-related ejections, lying-down ejections, and even an episode perfect for Father’s Day.

For this week’s theme, we wondered if the breadth of our senses could be encompassed in baseball ejections?

Well, let’s see!

I. Sight

On May 28, 2002, the Seattle Mariners played the Tampa Bay Devil Rays at Tropicana Field in St. Petersburg, Florida. Before the ninth inning began, the Rays’ production crew queued up a video highlight package built around the team’s one big inning that night. In the third, with two outs and the bases loaded, right fielder Ben Grieve worked a full count and drew a walk, driving in a run and prolonging the inning. The pitch was close, but with the benefit of replay and a superimposed strike-zone graphic, it looked like a strike. The Mariners’ manager, Lou Piniella, also thought the pitch looked strike-ish, and he came out to share these sentiments with the home plate umpire, John Shulock, who let the famously combustible Piniella say his piece. That would have been the end of it, but the next batter, catcher John Flaherty, hit a grand slam.

The eighth inning highlight package offered the fans a big-screen review of the whole sequence, including Grieve’s contribution: failing to swing at a strike and allowing Shulock to put him on base.

As Grieve’s free pass was shown on the big board, Piniella could not resist. “I told [Shulock] they were showing him up on the scoreboard,” Piniella said. “I told him to take another look at his calls.”

Piniella wanted a fire and he’d tossed a match. Shulock went up quickly, telling Piniella to “get the hell out of here” and giving the jerking thumb motion that made it official.

Sweet Lou marched out of the dugout and began raving. “Nothing you could put in the paper,” he said afterward. Shulock stood back and watched impassively as the manager kicked dirt onto home plate once, twice, and then, with the improvisational skills of a true virtuoso, Piniella knelt down and scooped dirt over the plate with his hands. 10,000 fans filled the roofed stadium with echoing calls for “L-O-O-O-U” and dreamed of the day he’d blow his stack for them. Nearby, the Rays’ leadoff batter, Flaherty (again), tried to make himself as unobtrusive as possible. “That’s one of the best ones I’ve seen,” he said of Piniella’s performance.

Once home plate was entirely buried, Piniella stormed off, leaving a dilemma of responsibility. Seattle’s catcher, Dan Wilson, waited for Shulock to excavate the plate, but the umpire settled into his pitch-calling crouch. A point was being made.

“If he wasn’t going to clean it,” pitcher John Halama said, “I’d have walked in from the mound to do it. How can you throw a strike—or call one—if the plate is underground?”

Wilson bent over and began clearing the plate with his hands, then stood to have a quiet word with Shulock. The umpire handed Wilson his brush. “I can’t talk about an umpire,” the catcher said afterward. “I don’t argue balls and strikes. He didn’t tell me to clean it. We had a discussion, but I can’t tell you what was said.”

Shulock said almost the same thing. “What was said out there doesn’t need to be discussed. He asked for my brush.” Wilson swept up his manager’s mess and the game continued. Piniella saw none of this, of course, but he was told of it afterward.

“If I’d still have been out there, Danny wouldn’t have [done that],” Piniella said.

It’s the umpire’s job, that’s why they give him a broom. The catcher doesn’t have the broom. I wish I’d been catching. I’d have put more dirt on the damn plate. I would have gotten one of those wheelbarrows full of turf and dumped it on the plate. He’d have needed a broom and a towel and some Windex.

Someone asked Piniella if he thought Shulock had “taken kindly” to his advice to watch the big-screen replays of his calls. “He didn’t take it too kindly and you know something? I really don’t give a [unspecified expletive]. How’s that? I don’t give a [unspecified expletive] if he took kindly to it or not.”

Elsewhere, Ichiro Suzuki could not have been more thrilled (except if the Mariners had won). Ichiro had been with Seattle since the start of the 2001 season, but Mount Lou had been rather inactive since then. “Before I came to the United States, that was exactly my image of Lou,” the outfielder said of the night’s eruption. “I often saw him that way on television.”

In a world of bigger screens and ever-clearer resolution, there was still nothing like seeing greatness with your own eyes.

II. Smell

For smell, we circle back to 1907, an excellent vintage for forfeits, ejections, and related hijinks, it seems.

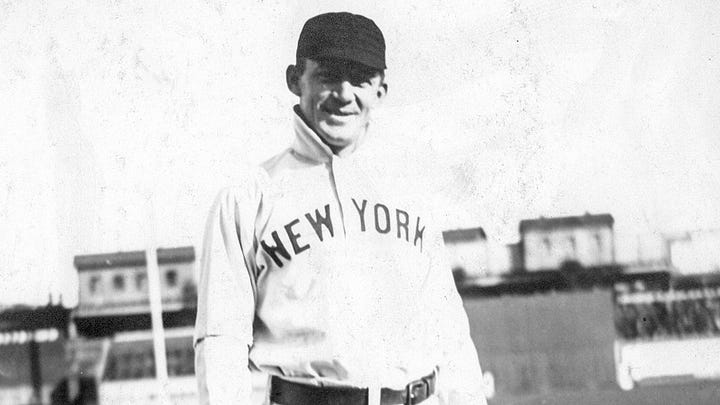

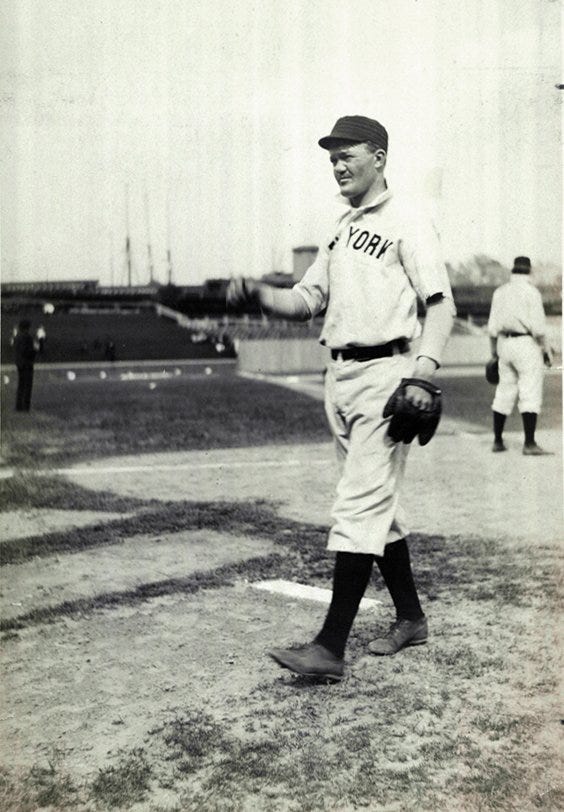

And it’s the New York Giants, naturally. Under manager John McGraw, the Giants were were regarded as the bad boys of the National League. This reputation clearly followed to them in Pittsburgh, where they played on September 25, 1907.

“TRIED TO MAKE FARCE OF GAME”

blared the next-day headline in the unfriendly Pittsburgh Press. The sub-headlines were key in those days:

“Rowdy Tactics by New York Giants Repeated Yesterday When They Saw They Were Being Overwhelmed”

The series at Exposition Park was officiated by the Giants’ regular nemesis, umpire Bill Klem, and it was just like old times. In the first two games of the series, six New York players had already been ejected, and “in each case,” the Press wrote, ”Klem’s action was justified.”

Before the third game even started, Klem added another notch, ejecting catcher Roger Bresnahan (who was coaching at third base, a responsibility typically handled by players at the time) for “making some reply.” Bresnahan was told to sit down, but when he refused to shut up, Klem threw him out of the park, so call it seven-and-a-half.

The game quickly went south for the Giants, whose least-accomplished starter, Mike Lynch, gave up an enormous seven runs in the second inning. McGraw replaced him with Cecil Ferguson, who would also give up seven runs. This was an absolute drubbing by dead-ball standards, and the Giants knew by the third inning that they were toast.

To amuse themselves, some of the New York players decided to workshop a bit of vaudeville. In the third inning, the Giants’ shortstop, Bill Dahlen, walked up to the plate to bat. Just as he settled in, George Browne, one of the team’s outfielders, ran out of the dugout with a bouquet of flowers, but “Dahlen turned up his nose and said, ‘They’re not for me. Give them to Klem.’”

Other than refusing the flowers, it is not clear how the umpire reacted to this stunt. Technically, we must say, Dahlen was not ejected for the flowers (nor was Browne). Klem let Dahlen proceed with his at-bat, for a single pitch, which Klem called a strike. Dahlen turned to argue1 and then Klem told him to “vamoose.”

The party was not quite over at that point, according to the scornful Pittsburgh Press account. In the sixth inning, the Pirates’ player-manager, Fred Clarke, slid hard into third base, “barely touching” third baseman Art Devlin with his upraised spikes. Devlin may have disagreed with that characterization, as he subsequently “quit the game” with an injury. The end of the season being four days away and the game score being what it was, manager John McGraw threw in the towel, inserting one of his favorite players, pitcher Luther Taylor, to fill in at third base.

The Press was rather hard on this decision. Here’s what they said, and then we’ll explain.

McGraw tried to turn the game into a farce by sending ‘Dummy’ Taylor, the loud-mouthed mute, to cover third base.

Luther Taylor was deaf, and the writer used a pejorative nickname often assigned to deaf people in this era, including Taylor and his baseball contemporary, Billy Hoy. Taylor’s lifelong condition had not stopped him from becoming an accomplished pitcher, so much so that when McGraw took over the Giants in 1903, Taylor was one of only a handful of players that survived the ensuing purge and played under the new regime.

Taylor was so integral to the team that new Giants players were expected to learn sign language in order to be able to communicate with their teammate, who was also frequently deployed to the sidelines as a coach.

The pitcher was known for his sense of humor and he often used his disability to make others laugh. When he figured out that some people didn’t like the way his voice sounded, he used it liberally in the coaching box, making piercing and hopefully distracting vocalizations, which explains the “loud-mouthed” reference in the quote above. In 1904, an umpire, Chief Zimmer, actually ejected him2 for making too much noise.

And while it was true that Taylor had never played the infield before that day in 1907, he was still a ballplayer and a fine athlete. He held his own at third and even got a defensive chance. When he threw out a fast runner at first base, he was saluted by the Pittsburgh crowd, which, according to one account, “applauded Taylor to the echo.”

III. Touch

We were worried about this one. How does one get ejected for touching? This isn’t the NBA. Fortunately, the perfect candidate was right in our archives, a 2022 incident we mentioned in a footnote in our overview of ejections.

On May 4, 2022, Madison Bumgarner started for the Arizona Diamondbacks, facing the Marlins in Miami. Bumgarner had a rocky start, giving up a leadoff home run to John Berti, and though he proceeded to strike the next three hitters out, he was visibly unhappy with the strike zone of home plate umpire Ryan Wills, with much glowering, muttering, and performative body language. First base umpire Dan Bellino didn’t appreciate it.

As he finished the half inning, Bumgarner continued to chirp at Wills, but he stopped in front of Bellino to receive the requisite sticky-substances hand check, which…went a bit long. Really, you just have to watch it. Words can only do so much.

Once he realized that Bellino was messing with him, the ill-tempered Bumgarner did exactly as Bellino hoped, yelling and swearing and earning the ejection Bellino wanted to give him. The pitcher had to be held back by teammates and coaches and it’s hard to blame him. This was entrapment, plain and simple.

“You guys have seen the video,” Bumgarner said to reporters afterward. And yes, they had. “I don’t know if I could say anything that would make the situation better. Obviously I didn’t go into the game with the intention of throwing one inning. Everyone picked me up today.” The Diamondbacks had rallied in the ninth inning to come away with an 8-7 victory.

Across the ballpark, Bellino told a reporter that Bumgarner’s profanity resulted in the ejection. Context being everything, the umpire was asked about the distinctly non-regulation hand check. “I wouldn’t say he took exception to it. It was just a hand check,” Bellino said.

Two days later, it was no longer just a hand check, and Bellino issued a statement of apology.

“When I began my MLB career almost 15 years ago,” Bellino wrote, “I received some good advice. I was told to umpire every game as if my children were sitting in the front row. I fell short of those expectations this week.”

ESPN reported that Bellino faced some unspecified discipline for the run-in, but he was not suspended. The Bumgarner incident appears to be the only time in his career when Bellino was featured in an episode of the “Ump Show.” In 2023 he was promoted to crew chief and we say good for him.

IV. Taste

This episode was originally filed under “smell,” because, according to the Retrosheet ejection records, Bobby Bragan’s July 31, 1957 ejection came after he “held [his] nose” in response to a call at second base.

Bobby Bragan, it turns out, is something of a major deity in the pantheon of bad baseball behavior. He managed for approximately 4.5 years between 1956 and 1966 across three teams, but he was ejected 22 times, which, per capita, is a lot.

According to LIFE magazine, Bragan’s shadow was already long when he arrived to manage the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1956:

At Hollywood in the [minor] Pacific Coast League, he once registered a complaint by lying down on home plate and pretending to read a newspaper. At various times he did a strip act in the dugout, sent up eight successive pinch hitters for the same batter, and sent one of his coaches onto the field wearing eight wrist watches after a dispute over a curfew.

Yes, Bobby Bragan is a man Project 3.18 is glad to know of.

On July 31, 1957, the second-year manager was in the midst of a feud with one of the National League’s four umpire crews, headed by Frank Dascoli. Just the day before, Bragan told reporters that he’d sent a cable to Warren Giles, president of the National League, requesting that Dascoli’s crew be “broken up.” The issue was this crew’s atypically-short fuse.

Bragan had not gotten a response by the next day, but reporters confirmed the president had gotten his message. “I will tell him we appreciate his interest,” Giles told them.

During the July 31 game at Milwaukee’s County Stadium, in the Braves’ fifth inning, their pitcher, Bob Buhl, advanced from first to third on a single by Red Schoendienst. The Pittsburgh defenders believed Buhl failed to touch second base on his way around the diamond, and argued this point with the second base umpire, Stan Landes. According to Bragan, “Landes called [Buhl] safe looking right at me in the dugout,” a gesture the manager interpreted as showing him up. “I looked right back at him and held my nose and sat down.”

Landes ejected him for this trivial offense, but Bragan was not one to accept a badge he hadn’t earned. He quickly sent one of his coaches, Danny Murtaugh, out to see one of the concessionaires. Murtaugh procured a pint carton of orange soda, with a straw, and returned, handing the beverage off to Bragan.

The manager jogged back out onto the field, casually sipping his soda. The crowd, who knew his prior work, began howling with delight. Bragan strolled calmly over to the umpire crew, gathered behind the pitcher’s mound, and offered each one a drink. All four men declined. “I guess they weren’t in the mood,” Bragan said. Dascoli did the only thing he could do and ejected the already-ejected manager once again, as theatrically as he could manage. Now Bragan could depart, to the sounds of applause.

Like any great artist, Bragan saw room for improvement in the performance. “We tried to get a hot dog, too. My only regret is that the hot dog was a little late in arriving.”

“I wouldn’t pull this stuff with other crews,” he added. “Other crews will listen to a beef and then tell you you’ve had your say. These birds won’t let you get a word in.”

Bragan told reporters that Dascoli and his crew were responsible for 30 of the 40 ejections in the league thus far that season. Giles, who managed the umpires, would say this figure was “far from correct.”

But was it? To the spreadsheets!

By August 1, 1957, there had actually been 54 ejections in the National League (including Bragan’s pop-comedy; which we’re only counting as one offense). Members of the Dascoli crew were responsible for 20 of them, 37% of the total. And while 37% is far from 75%, it’s not 25% either, which is what you’d expect from each of the four umpire crews if all things were equal. And we’re not even counting August 4, when Bill Baker, the most junior on the umpire team, would throw out four more players in one day’s work.

So, Giles was right to say Bragan was exaggerating, but Bragan was right to say that this crew was no good at listening.

After the game, reporters found Dascoli, Landes, et al. in the umpires’ dressing room, where they took turns calling Bragan “bush,” and talking with Giles via phone, giving their report of what had happened.

“Why don’t you get a picture of Bragan drinking that soda,” Dascoli suggested, “and say, ‘This is Manager Bobby Bragan of the Pittsburgh Pirates performing his duties,’ and then tell where the club is in the standings.”

Giles fined Bragan $100 and threatened an indefinite suspension if he ever pulled a stunt like that again. Unfortunately for Bragan, his indefinite suspension actually sounded pretty appealing to the Pirates, who went ahead and fired him on August 4, “for the general welfare of the club.” Considering that Danny Murtaugh replaced him, we’d say the Pirates got that right.

Sight, smell, touch, and taste (and smell again). That’s four out of the five, and all five if you count the mention of the time that Luther Taylor got ejected for making too much noise.

We did find a “sound” story, but once we dug in, we realized it was too good to bury in an ensemble. So we’ll do it right, next week. Bring ear plugs.

On September 30: “Hughie’s Tin Whistle”

In the dead-ball era, arguing with an umpire was nearly always described as “kicking,” evoking the image a recalcitrant stock animal. Often you get no details on the dispute, just that someone “kicked” and “got the thumb” or “was banished.”

The Retrosheet ejection records cite Taylor’s offense as “bench-jockeying.”

Once again a bang up job. The efforts necessary to produce these articles would wear me out. This political year it's Monday's smiles that keep me going. Thank you for your hard work.

Nicely done, Paul. Bobby Bragan is a name I’ve heard, and I think he was around the game a very long time (Wikipedia pegs his career at 73 years) but don’t really know much about - he sounds like quite a character.