Shadow Play - Part 1 of 2

A devastating blackout changes the game (and the city).

If you glance at the details for the July 13, 1977 game between the Chicago Cubs and the New York Mets, at first, nothing seems particularly amiss. All nine innings are present and accounted for, and the Cubs won the game, 5-2.

The record shows the game began at 8:05 pm at Shea Stadium in the borough of Queens in the city of New York. 14,000 people came to see the Mets play their old (relatively speaking) rival.

And we can see that it was hot, with evening temperatures at the ballpark nearing 80 degrees1.

But if you look a little closer, you see a disclaimer:

Game was suspended in the bottom of the 6th with the score 2-1 and was completed September 16, 1977.

That innocuous text is the only clue hinting at this box score’s…ahem…dark secret.

When the game began, the Cubs were in first place in the National League East, powered by an overperforming lineup featuring several players hitting well over .300, including center fielder Jerry Morales and third baseman Steve Ontiveros.

Across the diamond, the Mets were having a tough month. Sure, they were riding a three-game winning streak, but those three were the only games they’d won since June. Off the field, the team had literally traded away their Franchise: Tom Seaver had been shipped to Cincinnati less than a month earlier, shocking fans and souring people on the team’s leadership, particularly that of M. Donald Grant, the Mets’ chairman and chief decider. Pieces from the great Mets teams remained: pitcher Jerry Koosman, shortstop Bud Harrelson, catcher Jerry Grote, and first baseman Ed Kranepool, but ten years after they burst out of their expansion doldrums, the Mets were all out of miracles and back in the cellar.

Koosman started the game that night, facing Ray Burris of the Cubs. The veteran had really good stuff that night, striking out ten batters in the first six innings, but in the second inning, Jerry Morales walked and Steve Ontiveros hit a home run behind him. Koosman rallied and struck out the next three batters.

The banks of arc lights illuminating this scene were powered largely thanks to the Indian Point nuclear power station, some thirty miles north of the city. The New York regional power grid was managed by the Consolidated Edison Power Company, which was also responsible for delivering Indian Point’s electricity to the city in a usable voltage. Three days earlier, on July 10, as a suffocating heat wave descended on the area, Con Edison’s chairman, Charles Luce, said the utility was in its strongest position in years and that he anticipated no blackouts or brown outs that summer. On the evening of July 13, as the Mets and Cubs played to the south, heavy storms moved through the Hudson Valley, throwing off prodigious qualities of lightning, some of which struck the main power lines that connected Indian Point to the regional power grid, severing the links.

To those without electrical engineering credentials (moi) the particulars read a bit like Star Trek technobabble2, but the upshot is that three successive lightning strikes exposed some hidden system flaws and exacerbated the usual human failings. At one point Con Edison tried to activate a “fast-start” backup power facility only to discover there were no staff on site to throw the switch.

Plenty of power was available from nearby regions via the New York Power Pool, but without three main points of connection, the city grid found itself trying to drink from the proverbial fire hose. After two successive brown-outs (reducing voltage) failed to ease the strain, Con Edison began desperately “shedding load” (reducing overall usage by cutting power to specific places). The grid system, unfortunately, interpreted the targeted black outs as signs of a major short-circuit, and, to protect itself from greater damage, the whole thing shut down.

At 9:34 pm, nine million Con Edison customers, including the entire city of New York, were abruptly plunged into darkness.

The good news, if there was any, was that the outage had missed the evening rush by several hours and transit officials had seen the power spikes and fluctuations as the danger signs they were. Across the city, dispatchers ordered subway trains to head for the nearest station and stay there, a decision that left only a handful of trains and a few thousand people stuck between stations when the power failed. During the last major blackout, in 1965, nearly 800,000 people had been stuck on rush-hour trains that had no warning before the power cut.

New York’s mayor, Abraham Beame, was at a campaign event in support of his reelection, the prospects of which were about to take a huge hit. After the lights went out and the scope of the outage became evident, Beame quickly declared a state of emergency.

9:34 pm was the bottom of the sixth inning at Shea Stadium. Jerry Koosman had just grounded out, and the leadoff hitter, Lenny Randle, had stepped into the box to face Ray Burris.

Randle, a Project 3.18 alum who we last saw in 1974 with the Texas Rangers, involved in the precursor brawl to Ten Cent Beer Night, had been traded to New York at the start of the 1977 season. As he stood in, Burris began his wind-up, and then everything went dark. The banks of arc lights above the field, the concession lights, and the corridor and ramp lights flickered and then went out.

“I thought, ‘God, I’m gone,’” said Randle. “I thought for sure He was calling me. I thought it was my last at-bat.”

“I stayed at the mound for a minute, thinking it was just temporary,” Burris said. “Then I looked around [at the city] and realized we were in trouble.”

There are conflicting accounts regarding what happened as the power failed. Did Burris throw a pitch? Did Randle swing? Did he connect? At the time, no one reported any of these things occuring.

“I’m just glad he didn’t throw that pitch,” the Cubs’ catcher, George Mitterwald, said in the next day’s Chicago Tribune. Mitterwald said that another Cubs catcher, Steve Swisher, was in the bullpen warming up reliever Pete Broberg at the time. “[Swisher] had just caught a pitch when the lights went out. I don’t know what I would have done if [Burris] pitched. Bail out, I guess.”

But in more recent tellings, at least Randle and perhaps Burris also recalled a pitch thrown and some creative effort by Randle to end up on base. If Randle did swing at something, at least we know it didn’t count, because he’d be up to bat again when the game resumed much, much later.

Shea Stadium had an emergency backup generator, and the team soon switched it on, powering a few dim overhead floodlights. The crowd gasped and cheered and hooted and waited for the power to come back.

Outside the park, the city was quickly transforming, for good and bad. Walk-ups and high-rises went solid-black against the dim light of a waning summer moon, until people inside found their flashlights and candles, making building windows flicker like medieval castles.

The traffic lights were out, of course, and the roads snarled. It would be hours before the NYPD and eventually the state police could get ahold of the traffic situation, and in the meantime, civilians armed with flashlights and portable lanterns left their homes to stand in the streets and direct traffic. “The drivers need help,” one amateur traffic controller said. “You don’t realize how dark this city is until this happens.” The headlights of all the cars, buses, and trucks transformed each street and avenue into a rope of light, weaving an illuminated net over the darkened boroughs.

There was plenty of generosity, kindness, and bonhomie on the streets as New Yorkers responded to their new circumstances. Toll gates on bridges across the city were without power, but the toll-takers remained at their posts and many cars stopped to hand over their coins.

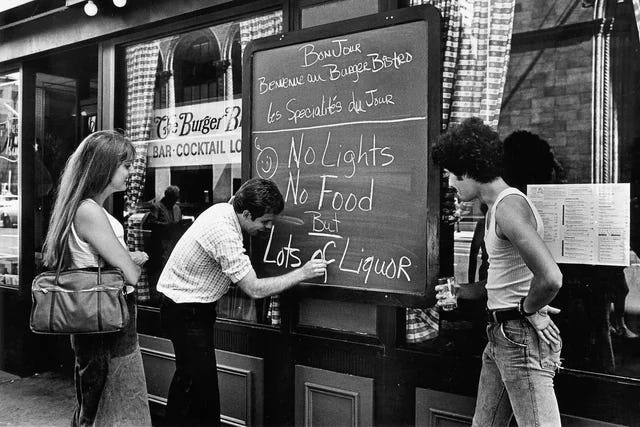

People passed out drinks and snacks to neighbors and passersby, and many restaurants stayed open as long as they could, a few even offering free food that was otherwise about to go to waste. Many bars remained open, of course.

Crowds filled Rockefeller Center, eager to look up at the darkened towers looming overhead and see the city from an entirely novel perspective.

At least one Broadway show went on after the cast and crew of Anna Christie decided to finish the third act by flashlight for any who wanted to stay to the end, earning a standing ovation they couldn’t see.

The dynamics of supply and demand were about to be turned upside-down, but anyone sitting on a good supply of candles quickly set up shop at street-level, where light cost 50 cents apiece “That’s regular price, mind you,” a defensive stationary store-owner told an inquiring reporter.

In the pitch-dark alcoves of Grand Central Station, candles were all anyone had to go by. A few workers there claimed to have been carrying candles in their pockets since the 1965 blackout, just in case it ever happened again.

The backup generator at Shea Stadium ensured that public address system and the organ remained on, and within seconds of the failure, Shea’s organist, Jane Jarvis, got busy. As we saw with Ten Cent Beer Night, organ music didn’t always keep people calm, but Jarvis, an accomplished jazz pianist away from the ballpark, played the hits, including “God Bless America,” “Jingle Bells,” and, wryly, “White Christmas,” which got many in the crowd to sing along.

Meanwhile, Mets officials tried to figure out what was going on. The stadium was surrounded by darkened New York on three sides, so the scope of the issue was clear, but not how long it might last. Some patrons began to file out, but many more sat and waited for news.

Without identifying himself (to avoid the inevitable Seaver-related boos) Chairman Grant used the PA system to address the crowd. In calm, assuring tones, Grant explained that the power failure was citywide, and that Con Edison was working on the problem. The power utility was not well-regarded in the city or in the Mets’ broadcast booth. “I have about fifteen remarks I could make about that,” radio broadcaster Lindsey Nelson said, “all of which would get me in deep trouble.” For the Cubs, Jack Brickhouse got back on the air over a special phone connection and told WGN listeners that the power cut was more proof that nighttime baseball was fundamentally unnatural.

Chairman Grant encouraged fans to stay if they wished until more information was available. “This is the safest and coolest place to be–right here,” he said. “Thank God for our auxiliary power. There is no fan like a Met fan. God bless you.”

Con Edison officials wasted no time in framing the incident as the result of “an act of God” and warned New Yorkers that turning on a power grid was a “long and tedious” process, one that would take at least six hours (the goalposts moved overnight and officials targeted a late morning restoration for most of the city).

Mayor Beame urged people to stay indoors and stay in their homes, but this was easier said than done, even for the majority of the population who wanted to be helpful. This was the city that never slept, with hundreds of thousands of people out of their homes when the lights (and traffic lights) went off. Midtown Manhattan’s main traffic arteries quickly became sclerotic and the baking night air was filled with the sounds of horns and sirens that never seemed to move. The sidewalks were filled with conversation and adrenaline.

5,000 off-duty officers joined the 3,000 who’d been working before the lights went out. Before the night ended, all 25,000 officers of the NYPD were called in to work and placed on indefinite 12-hour shifts.

Hospitals across the city shut down or went into emergency operations. The backup generator at Bellevue Hospital failed, forcing staff to manually provide life-support to intensive-care patients—despite their heroic efforts, several people died.

The city’s two major airports closed, and the tunnels providing a key means of escape were also shut down—without their ventilation systems, the tunnels could fill with poisonous carbon dioxide and other exhaust fumes.

The New York Telephone Company reported a “capacity problem” on its system and asked residents to stay off their phones barring emergencies, but there were plenty of those, with thousands of people stuck in high-rise elevators. Rescuing these stranded became the fire department’s immediate priority after the blackout, and the entire FDNY undertook a “leg day” to remember as they trudged up and down unending flights of ink-black stairs.

New Yorkers began setting up camp in their lobbies, unwilling or unable to brave those same stairs and the stifling, darkened conditions that awaited them above street level. Some began lighting fires in trash cans and other receptacles, and the elevator calls soon gave way to reports of fires that had gotten away from their creators, accidentally or on purpose.

Jane Jarvis’ Shea Sing-along playlist had started over. One columnist felt she’d played “God Bless America” “at least 25 times,” but there were still thousands of people in the stadium, waiting.

The Mets’ business manager, James Thomson, had quickly and wisely closed the concession stands to keep beer out of the equation. He now suggested the players do something to keep the crowd diverted, leading to ten minutes of baseball like no other in the history of the game.

The gate out into the parking lot behind center field was opened and two of the Mets’ players, Joel Youngblood and Craig Swan, along with an obliging groundskeeper, drove their cars onto the outfield grass, pointing their lights towards the darkened stands. “They owe me a lot of gas for this,” Swan said.

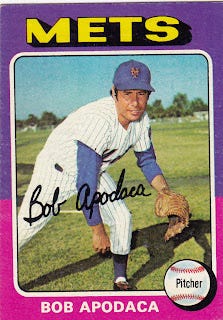

Next, six of the Mets took the field. Illuminated by the car headlights in center, reliever Bob Apodaca took a bat. Jerry Grote was behind the plate. Jackson Todd at first, Doug Flynn at second, Bud Harrelson at shortstop, and Bobby Valentine at third. Harrelson’s presence was particularly strange, as he had a broken right hand and was wearing a cast, but it didn’t really matter, because there was no baseball.

Instead, Apodaca pretended to hit a ball and the infielders would drill, executing a flurry of defensive plays and phantom relay throws. Not having many in-game opportunities, Apodaca even practiced his base-sliding, sending clouds of dust into the light of the hi-beams. The display was so serious that at one point, writer Red Foley, the night’s designated scorekeeper, determined that Bobby Valentine had made an error. The shadowy game went on for ten minutes and then ended as spontaneously as it had begun.

The “team” dispersed to the foul lines to talk with fans and sign autographs. The Mets’ manager, Joe Torre, visited with his wife and children, who were seated near the home dugout.

“I’m not scared,” Torre said. “If we had 30,000 or 40,000 people in the stands, that would have been scary.” “It’s a good thing we didn’t,” Rube Walker, the pitching coach, said. “People would be playing bumper cars in the parking lot.” As it was, the few thousand remaining in their seats compared destinations with many drivers offering carpool services to the unfortunates who’d arrived via the subway.

The delay stretched on into its second hour, and no end seemed in sight. The lights flickered briefly at around 10:30 pm, but that was all. Chairman Grant met with the Cubs’ manager, Herman Franks, and the umpire crew chief, Harry Wendelstedt, who decided to suspend the game until the following day. Grant made the announcement and everybody left.

Baseball had not exactly been an oasis of calm during the 1970s and certainly not in New York, but as the city went increasingly wild, Shea had kept its peace. Things had been so serene inside the stadium that the Mets director of security had sent his staff out into the streets around the ballpark, where there was, unfortunately, much more to do.

The fans and the Mets made their way back to their homes as best they could, but for the 25 visitors from Chicago, home was a hotel in Midtown Manhattan, and their ordeal was just beginning.

Do you have memories or stories of New York and the 1977 blackout? Share them in the comments!

Here’s the conclusion:

Temperatures are in Fahrenheit—we’re home at last!

“Slow-acting upgrade cycle;" “Line reclosure;” “EPS system failure;” “Phase shifters;” “Thermal overload.” Four of these terms relate to the 1977 blackout and one is a problem if you’re traveling at maximum warp. If you can tell which is from Star Trek without looking it up, well, we’ll see you at the next convention.

The ‘65 blackout was more eventful for me. I was in HS & involved in CB radio at the time. I had jumped up on our roof to play with the antenna which was also close to our TV antenna. When I got back into the house I turned the TV on to find no channels broadcasting. I thought I had done something. My Father was on his way home & I got paranoid thinking I had done something; he wasn’t a fan of my CB by any means. Little did I realize the NY stations were off the air. We had power in Jersey but man…. I was SO relieved to find NY was in the dark, as horrible as it was.

Another good one, Paul! The ten minutes of shadow baseball was really creative. I particularly enjoyed hearing about the organist, as well as the non-price-gouging stationer selling candles. New Yorkers are the best.

If and when you ever run out of ideas, I would love to hear about the 1972 All Star Game: such greats on both the AL and NL rosters! Carl Yastrzemski, Jim Palmer, Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, etc. Meg