Shadow Play - Part 2 of 2

In 1977, the Chicago Cubs struggle to escape from New York.

We began with the Mets, but our story switches to the Chicago Cubs as they navigate the 1977 New York City blackout.

Here’s the first part, if you missed it:

In 1977, most nationally-distributed news originated in New York. All three major television networks broadcast from the city, and after the power grid failed, all of those channels briefly went off the air while secondary systems were turned on (or hurriedly worked out).

In that era, most national news printed in the country’s small and even medium-size newspapers was delivered via the “wire reports,” transmitted by teletype from organizations such as the Associated Press and United Press International, based in New York.

Depending on this system (whether they knew it or not), many Americans picked up their papers as usual on July 14 to read up on the overnight sports scores, only to find a brief, explanatory blurb of apology in their place: without the wire services, many papers actually didn’t know the outcomes of the previous day’s games. In modern America, the free flow of information has become effectively disaster-proof, but less than fifty years ago, one localized event effectively dammed the nationwide distribution of news.

Up in the Shea Stadium press box, now illuminated by candlelight, some 35 reporters tried to submit their usual dispatches. The New York reporters were out of luck—the local phone lines were jammed and their newsrooms didn’t have power, either—but the traveling and New Jersey-based reporters delivered their articles by dictating them over the phone while someone on the other end typed.

One intrepid reporter left the press box, trying to make his way down to the clubhouse for interviews. He asked a stadium worker for tips on navigating there in the dark. “My suggestion,” the guard said, “is to find a lighted corner, sit down, and stay put.”

Undeterred, the reporter felt his way along the cinder block corridors until his hand pressed into something alarmingly soft and squishy. It turned out to be the umpire, Harry Wendelstedt, holding a chest protector out in front of him as he led his crew out of the catacombs beneath the ballpark.

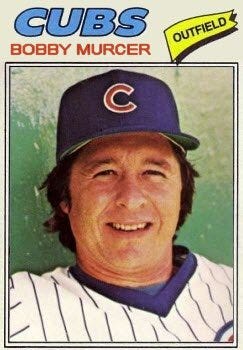

The visiting clubhouse was pitch-black. “Welcome to Fun City,” joked right fielder Bobby Murcer, a long-time Yankee until he was traded to San Francisco in 1974. “This would never happen at Wrigley Field.” Many tried their hand at this joke. “We don’t play with lights in Chicago, but this is ridiculous,” catcher George Mitterwald said. And so on.

The Cubs were impressed by the Mets’ fans, who’d been conspicuously well-behaved. “Can you imagine if a few hundred of them decided to storm the dugout?” catcher Steve Swisher said. “They’ve done it before, in broad daylight, too.”

In the darkened clubhouse, the Cubs drank beer and ate leftover fried chicken. Some tried to shower while holding flashlights, mostly succeeding, until it came time for that essential 1970s act of grooming. “No hairdryers!” Mitterwald lamented. Elsewhere, one of the Cubs’ coaches, Jack Bloomfield, was observed arranging his hairpiece by flashlight, with no heat-treating necessary.

Herman Franks, the Cubs’ manager, stumbled and swore, asking for directions to the men’s room. “And where’s my cigar?” he demanded, knocking over a chair.

The half-showered, half-fed Cubs groped to their charter bus and left for the Waldorf Astoria, their Manhattan hotel, at approximately 11:30 pm. Now all they had to do was navigate a three-hour traffic jam in a city that seemed to be coming apart.

On the slow crawl into Manhattan, the Cubs saw looting from their bus windows and realized their ordeal was hardly over. One player remembered staring out at the silhouette of the darkened Empire State Building as they passed nearby, only its base illuminated by headlights and passing emergency lights, as sirens wailed from all directions. “What an eerie sight. It’s like war.”

“Don’t stop for anything,” the Cubs told the driver, who somehow got them to their destination. Even disembarking felt precarious. “Remember,” somebody said, “we all enter the hotel as a group.”

The hardy staff at the Waldorf Astoria were ready for the Cubs, helping them find their rooms by candlelight. Unfortunately, many were lodged on the 14th floor or higher. Bill Buckner and Randy Hundley were in particularly dire straits, as both were nursing leg injuries and now faced the dark and unforgiving stairs.

Before going to his room, reliever Pete Broberg discovered a novel source of potable water on his floor: the melted remnants of the ice in the ice machines. He filled a cup, making him one of the only Cubs able to brush his teeth before turning in.

The battle the Cubs glimpsed on New York’s streets that night had many dimensions, but at base it was a clash between humanity’s best and worst impulses. Many of the grace notes we have already played, but as the minutes ticked by in darkness, parts of the city tilted towards unrest and then tumbled into chaos.

The night’s sins ran the gamut. Cab drivers set exorbitant prices for stranded passengers. A few gas stations charged $1.50 for a gallon of gas ($7.79 in today’s dollars). Restaurant patrons walked out on their bills under the cover of darkness and confusion. Some stores pushed customers out onto unsafe streets in their haste to close and lock up. Their air conditioners having gone still, people opened fire hydrants across the city, seeking relief from the heat and greatly reducing the water pressure available for working fire fighters, who would soon be desperate for every drop they could get.

But the largest and best-remembered evil of the blackout was the wild, destructive looting committed by thousands of New Yorkers who saw the loss of power as the signal for a property-crime variant of the Purge.

It would take a day before the scope of the crime and devastation could be fully appreciated. In the harder-hit neighborhoods, like Spanish Harlem, the South Bronx, Bushwick and Crown Heights, and Jamaica in Queens, the looters outnumbered the police by orders of magnitude. Crowds of people pushed up and down the commercial streets, breaking glass, ripping away protective gates, and helping themselves. Given the late hour, many businesses were closed, emptied, and undefended. Car dealerships had their inventory hotwired and driven off. One motivated crew somehow made off with a 1,000-pound safe. Before it was over, every borough but Staten Island had suffered widespread looting.

“It was the 1965 blackout and the 1968 riots all rolled into one,” an officer said. Hundreds of people were caught in the act and arrested. Police stations began to resemble big box stores, filled with stolen goods confiscated literally out of the hands of the thieves. The number of detainees quickly filled New York’s lockups to capacity and police were ordered to stop arresting people for petty theft or vandalism—there was nowhere to put them. The city was forced to temporarily reopen the Tombs men’s prison—closed in 1974 for conditions so bad that they threatened to violate prisoners’ constitutional rights—to relieve the overcrowding. More than 3,500 people were arrested, but the NYPD was praised for the restraint officers had shown in responding to the looters, many of whom were described as “little more than children.” There were just a few reports of alleged police brutality.

The 9-1-1 emergency center received 5,000 calls an hour, compared to the usual 750. Some people attacked emergency response vehicles and the workers inside them. One police officer took a bullet in the leg while directing traffic. Some 430 police officers and 42 firemen were injured, 18 seriously.

The firefighters were caught in between two fronts of danger. On the best of nights that summer, economically-depressed New York struggled with an arson problem, as empty and derelict buildings all over the city burned for amusement or insurance money. June 13 was far from the city’s best night. Barrel fires gave way to burning buildings and the firefighters trying to reach them fought through (and sometimes with) crowds of people only to pull up next to destroyed hydrants. The lucky ones fought fires from ladder trucks while looters continued working beneath them.

The mayor’s office would initially report 650 fires citywide, a figure one dispatcher in Queens found comically low. “You must be kidding me. I haven’t counted these things. In terms of the number of fires, the number of emergencies, it’s one of the worst disasters I’ve ever seen.” He was right—the final tally landed above 900 fires, 55 of which were major.

Whole streets were looted out, such as on St. John’s Place in Crown Heights, and Flushing Avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Third Avenue in Harlem was “demolished,” a police officer said. “It’s like a bomb hit it.” Cleaning up their looted shops, some merchants vowed to reopen, but many did not, adding to the urban blight in the hard-hit areas.

The causes of the mass-hysteria that night are layered, complex, and best not summed-up with a paragraph in baseball-themed newsletter, but two comments from the time resonated with us.

The New York Times got a quote from a 14-year-old girl who paused plundering a drug store in East Harlem to explain that what was happening was far less extraordinary than it might seem to visitors:

It gets dark here every night. Every night stores get broke into, every night people get mugged, every night you scared on the street. But nobody pays no attention until a blackout comes.

Ernest Dichter, a behavioral psychologist, pointed out that this kind of collective behavior had long been described in people all over the world, not just in psychology and history, but in literature:

It was just like Lord of the Flies. People resort to savage behavior when the brakes of civilization fail.

The morning of July 14 brought little relief. The power was still out, and people were still out in the streets, now picking over the scraps left from the night’s large-scale clashes and avoiding the growing numbers of police, who turned the tide by posting officers on nearly every corner in hard-hit areas.

Mayor Beame ordered most nonessential businesses closed to keep people out of the streets. The mayor had just seen most of his hope for reelection go up in smoke along with parts of several neighborhoods, and he was furious.

Addressing the media that morning, he blamed Con Edison, saying the city had been subjected to “a night of terror,” with enormous losses to businesses, individuals, and the city’s economy. He condemned the utility’s characterization of the blackout as “an act of God.”

“We cannot tolerate, in this age of modern technology, a power system that can shut down the nation’s largest city,” Beame said. “Con Ed’s performance is, at the very best, gross negligence and, at the worst, far more serious.” He promised a blue-ribbon commission to investigate the company’s procedures. Responded Consolidated Edison Chairman Charles Luce: “That’s a little like saying, ‘We’ll have a fair trial before we hang the defendant.’”

It was another day of 90-degree humidity and the city’s airless canyons were choked with the mingled smells of smoke and trash. These were also roughly the conditions in the sweltering lobby of the Waldorf Astoria, “humid, acrid, and overpopulated” as the Cubs manhandled their luggage down a dozen flights of stairs at the end of a restless night.

“I have a severe case of luggage elbow,” said Broberg, who’d been all the way up on the 17th floor. “I think I was the highest of anybody. Most of the team was on the 13th—naturally.” As far as anyone knew, the day’s game(s) at Shea were going ahead, and it was a getaway day for the Cubs, meaning they had to pack up and check out before heading to the ballpark.

There was no water pressure or telephone service. The players were sweaty, unshowered, and only the enterprising Broberg had managed to so much as brush his teeth.

Scouting parties determined that the only nearby place open and serving food was charging a dollar for a plain bagel. “With no lox!” Sensing an opportunity, one player tried to sell a package of mints for five dollars.

The Cubs checked out, signed some autographs in the lobby, and shared stories from the previous day’s events as they waited for their bus.

Lou Boudreau, a renowned former player, was working as part of the Cubs’ broadcast crew and traveling with the team, and he’d suffered greatly on July 13: “I had all my money taken,” Boudreau said. “But that happened in the afternoon—at the race track.”

Strolling into the lobby from the street, looking and smelling remarkably fresh, Bobby Murcer thought he had a great story.

The former Yankee had used his New York smarts to great effect, escaping across the Hudson River and finding sanctuary with friends who lived in New Jersey, where the power remained on. “Real nice over there,” Murcer told everyone. “I just came from a breakfast with friends in an air-conditioned restaurant.”

“What are all the candles for?” Murcer asked, clearly enjoying himself. “Is it somebody’s birthday?”

The power came back on at Shea Stadium at approximately 10:00 am. The Mets took batting practice and the gates opened at 11:45, and determined early birds began filing in. The Cubs were preparing to take their turn for batting practice when, just before noon, the power went out again.

The field was playable, but the Mets decided that the darkened bathrooms and nonfunctioning concession stands were not. The end of the July 13 game and the July 14 game were postponed; the former would now be finished on September 16. Manager Joe Torre certainly wasn’t complaining. Over the next three days his team was scheduled to play five games and host an Old-Timer’s Day.

The Mets went back into the darkened dressing room to change—nobody bothered to try and shower. “The first guy that says we’re a gamey bunch gets a pop in the nose,” Torre warned.

The Cubs took their batting practice and then departed for the relative sanity of Philadelphia. “Even Philadelphia,” pitcher Bruce Sutter said, “is going to look good after this.”

Around 10:00 pm, 24 hours later, power had been restored to all but 200,000 unlucky people on the Upper East Side, an area which happened to include the mayoral residence, Gracie Mansion. Con Edison officials seemed to have moved Beame to the back of the queue, as soon would many New York voters.

Just over two months later, on a drizzly day in early autumn, the sixth inning got back underway. The schedule had worked out such that the Cubs’ Ray Burris picked up right where he’d left off, eventually going the distance as the Cubs won, 5-2.

“I’ve got to be in the record books,” Burris said. “It must have been the longest complete game in history.” (It probably wasn’t, but that’s a rabbit-hole for another time.)

Time, always funny in clockless baseball, can get really funny during postponed games. When the Mets and Cubs got underway on July 13, 1977, the Cubs were in first place, but when the game ended, they were 15.5 games back from the Philadelphia Phillies, looking at a .500 record and fourth place finish. Mets shortstop Bud Harrelson actually managed to get an at-bat during a game he began with a broken hand in a hard cast.

The Chicago Tribune pointed out that when the game started, Elvis Presley had been alive, and Ernie Banks had not been a Hall-of-Famer. When it ended, the King was gone and Mr. Cub was where he belonged in Cooperstown. Nationally, the first Space Shuttle, Enterprise, flew and the United States Department of Energy came into existence.

New York had a particularly busy sixth inning. Abe Beame lost in the Democratic mayoral primary. David Berkowitz, the Son of Sam serial killer, was finally captured, ending an unprecedented season of fear in the city.

And in the Bronx, the Yankees stopped fighting amongst themselves long enough to take over first place in the American League East. After a dark summer in New York, the bright lights of October baseball were flickering hopefully.

Thanks for making Project 3.18 a part of your summer reading, everybody.

Next week, we’ve got some fun callbacks to some of our summer stories. We’ll have those for you on Tuesday, September 3, after the long weekend here in the United States. Until then, be sure to check your flashlight batteries and make sure you have a stash of candles on hand…because you just never know.

On September 3: “Postscripts - Vol. 2”

15-1/2 games out when the game finished - now, that’s the 1970’s Cubs that I remember.

The Cubs preceded the movie Escape from New York in 1981. This was a better story.