Snapped

In 1931, America’s most famous gangster asked the Cubs’ Gabby Hartnett to autograph a ball for his son. It would cost him dearly.

And we’re back. Did we miss anything?

Long before interleague play and well after the two teams were both good enough to bump into each other in a World Series, the Chicago Cubs and Chicago White Sox played an annual off-day exhibition game.

The White Sox acted as hosts in 1931, inviting the Cubs to Comiskey Park on the city’s South Side. The change of scenery was welcome for the Cubs, who had lost their last nine games in a row in the National League, and the White Sox, who’d lost seven of their last eight, were similarly ready for a distraction.

These exhibitions were played for the benefit of charitable causes, and on September 9, 1931, deep within the Great Depression, the need for charity was profound. Proceeds from the game, some $44,489 (about $912,000 in 2024 dollars), would go to an unemployment relief fund chaired by Illinois’ governor.

Many Chicago VIPs were present for the occasion: the governor, of course; Chicago’s Democratic mayor, Anton Cermak; and even the commissioner of baseball, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who kept his offices in Chicago and was photographed that day watching the game with his granddaughter, Joanne.

There was another celebrity in attendance who was more famous than the mayor, the governor, and the commissioner put together. He was seated in the front row of Box 29, just next to the Cubs’ dugout. He was large and heavy-set, wearing an expensive brown suit, with receding black hair, a broad face, thick lips, and a perpetually sleepy expression. The left side of his face bore several distinctive scars.

Others nearby marked his presence in murmured exchanges and discreet nudges to their neighbors.

“Look, over there. That’s Al Capone.”

During the 1920s and early 1930s, Chicago was so rife with organized crime and public corruption that mob organizations like Capone’s Chicago Outfit really did seem to rule the city. As the people in power, many mobsters inevitably found their way to the best seats in any house, including at Comiskey Park and Wrigley Field, where their presence created new and memorable ballpark hazards for unfamiliar players.

One visiting player, Pete Donohue, remembered standing in the coaching box at third for Cincinnati in a game on the North Side. The trouble started when he sent a runner home, where he was easily thrown out, ending the inning. As Donohue walked back to the dugout, “a gent in a nearby box told him what a flop he was as a coach. Donohue’s ‘Irish’ arose and he replied in kind. His critic answered with a huge Bronx cheer1.”

His teammates kept him from going into the stands to continue the conflict, and it was a good thing they did—his critic was a man named Al Weinshank, a high-up in the powerful North Side Gang (Weinshank was among those Capone later had killed in the famous St. Valentine's Day Massacre in 1929).

As the North Side Gang’s influence declined, Capone himself began showing up to enjoy baseball on what had been their turf. In 1932 or 1933, the St. Louis Cardinals were in town and one of their stars, Joe Medwick, argued a call at third base.

The crowd jeered Medwick, and “a voice from a nearby third base box seat was then clearly heard impugning his honor.” Fans and players got into verbal exchanges like this all the time, and the rowdy Cardinal followed his instincts and returned fire: “Aw, go jump in the lake.”

After the game, some of his more knowledgeable teammates informed Medwick he had just told none other than Al Capone to get wet. “You’re going to end up wearing a cement suit,” Frankie Frisch warned him. The next day, Medwick spotted Capone in the same box and walked over, chummily slapping him on the back to pay respect and make clear that there were no hard feelings.

Any group of hometown fans had their hometown favorites, and made men were no exception. Al Capone’s favorite player was the Cubs’ right fielder, Kiki Cuyler. We know this because in 1929, Capone had that sentiment engraved on a handgun he presented to Cuyler as a gift.

When we first heard that, we expected it would turn out to be apocryphal. Sure, Al Capone handed out guns as party favors. And Tim Cook sends out current-gen iPhones with his Christmas cards.

Well:

In September, 1931, Kiki Cuyler’s biggest fan was surely feeling a bit in limbo. A federal task force had finally gotten him arrested on charges that would stick. His trial was scheduled to start on October 6, less than a month away. He had agreed to plead guilty in exchange for a shorter sentence, and that autumn he must have been aware that time on the outside was likely short.

He still kept a busy schedule, sometimes working 12-hour days in his headquarters, the Lexington Hotel, near where McCormick Place is today. Capone had taken over room 430, actually a five-room suite, filling it with plush red carpets, mirrors, an improvised switchboard system, and innumerable large, nondescript men in shirtsleeves.

It was hard to find Capone, even if you had an appointment. The same week as the Cubs/Sox game, an extremely brave reporter from the Washington Post approached Capone in public to ask for an interview. He was told to come to Capone’s offices at 7pm that night. As he walked into the Lexington, he ran into Capone coming out. The gangster told him the interview was not going to happen that night, but to come back in the morning.

The reporter came back, but this time he was told Capone was out of town. On his way out of the hotel, he asked the front desk when Capone had left. “I haven’t seen Mr. Capone here in three weeks,” the clerk said, with such conviction that the reporter almost believed it himself.

As trial approached, Capone was doing his best to bank some quality time with his son, Albert (who people called Sonny), who accompanied him to the Cubs-Sox exhibition game. They were joined, at least for a while, by a state representative named Roland Libonati, who also moonlighted as a lawyer for members of the Outfit.

Behind Libonati and the Capones sat three or other four men, all wearing similar light-colored fedora hats with dark bands. At least two were guards, and one of those was Jack “Machine Gun” McGurn2, the Chicago Outfit’s most accomplished triggerman. McGurn kept his hat low over his face but was still spotted by streetwise journalists. Capone’s entourage kept their coats and hats on and kept their eyes on the crowd of 35,000, their faces drawn into tight, anxious lines. A popcorn vendor handing out someone’s purchase accidentally brushed McGurn’s shoulder and he jumped half out of his seat before realizing what had happened.

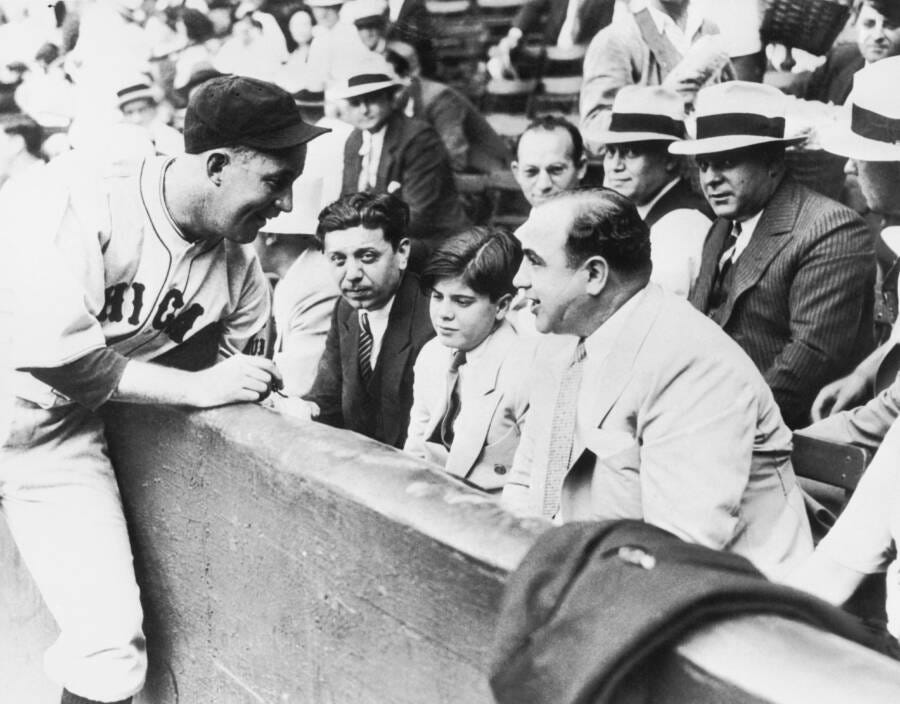

We know all of these details because this scene was photographed and slavishly described by the Chicago Daily Tribune, which had photographers stationed in the nearby Cubs’ dugout. Assigned to cover a meaningless intracity game, they had been gifted a fascinating tableaux of Americana. Capone, his son (almost never photographed), and a sitting state politician, Libonati, out enjoying a baseball game. This was a good photograph, but something was still missing. The photographers waited.

Before the game, while the players warmed up, Capone called out to someone, and Gabby Hartnett walked over. The Cubs’ catcher was famous in his own right, by virtue of being the best at his position in that era. In 1930, he’d broken his own record for home runs for a catcher by hitting 37, while simultaneously leading the National League in defensive performance. Hartnett was a big star in 1931, and it turns out that Sonny Capone was a big fan. Al introduced them and asked if Hartnett would sign a baseball. Hartnett said he’d be glad to. Somebody produced a pen. The nearby photographers got to work.

The resulting photos probably captured a truly candid moment—with his son present, it seems highly unlikely that Capone would have participated in staging this scene for the benefit of newspaper cameras.

Hartnett’s body language is natural and comfortable as he pointedly enters Capone’s personal space. In one frame he talks while Capone listens, in another it’s the other way round. They are clearly in conversation, though what was said, we don’t know. Just pleasantries, probably—the two do not appear to have been close; there is no record that Hartnett ever got his own custom .25.

In a third version of the photo, Capone is looking down into his lap, creating the uncanny impression of somebody checking their phone, but in 1931 all he had down there was a hat. In a fourth version, both Libonati and one of Capone’s other unsmiling companions are looking right into the camera. One wonders if that was the last shot before the photographer quietly packed up and left, before the game even started. In some versions, you can even see the arm of the hapless vendor handing out popcorn over Jack McGurn’s shoulder.

Many contemporary and later accounts say that Capone and Hartnett were pictured shaking hands. They probably did shake hands at some point, but that moment was not captured. Still, the two looked mighty friendly.

Hartnett handed over the ball, the brief interaction ended and the catcher went back to work. He went hitless during the game but just missed a second-deck home run that was foul by inches. The day’s hero was Cubs pitcher Charlie Root, who shut out the White Sox and drove in all three of the Cubs’ runs.

Capone stayed through the end of the game and departed through a throng of well-wishers, occasionally bowing to calls of “Hey, how ya’ doin’, Al?” before disappearing into a limousine.

The next day, one of the most iconic photos of the early 1930s ran in the Daily Tribune.

That morning, commissioner Kenesaw Landis opened his copy of the Daily Tribune to find a picture of himself and little Joanne next to a picture of one of the game’s biggest names palling around with the avatar of Chicago vice.

The photo moved across the country like a comet, trailed by a long tail of scorn and outrage. At this point in history, polemics could finally be broadcast out over the airwaves, and one (anonymous) commentator thundered into a microphone:

There are countless thousands of small boys in this country who would prize a baseball autographed by Hartnett; give every treasure they possess to have one, but their fathers are merely honest and hard-working carpenters, mechanics, or store clerks, and so they must envy this “kid” whose “dad” is the king of bootlegging and the most notorious outlaw in the world. Think what that means to the boys of our country, what an inspiration it is to them and what we must expect a few years from now in consequence of a condition such as this.

The real subject of the photograph was “an increasing public contempt for law observance” in Chicago that threatened to infect the whole country if not checked.

Capone had long ago become immune to bad press, and he continued living it up before his trial date and the two-and-a-half year sentence he expected would follow it. Eager to cram in all the fun he could, his next stop was a football game between Northwestern University and Nebraska.

He arrived with a flourish, escorted by a contingent of Chicago police, “like an emperor going to his coronation.” Once his presence was detected inside the stadium, the crowd at least had the decency to boo. A few weeks later, the chairman of the student paper published a “disinvitation” to future games, addressing Capone directly and saying, “You are not getting away with anything and you are only impressing a moronic few who don’t matter anyway.”

As he got closer to jail time, some of the Capone mystique seemed to be wearing off.

“The spectacle of management and players of baseball teams dancing attention on Al Capone of Chicago is a disgusting one,” wrote one editor.

People around any ball park should know better than to let baseball be associated in the public mind with a rascal of the Capone stripe. And if they do not, Judge Landis should tell them.

Publicly, Kenesaw Landis had kept quiet, but behind closed doors, he fumed. As the first commissioner of baseball, hired in the wake of a disastrous gambling scandal, Landis was obsessed with keeping the game free of corruption. He had largely succeeded, a feat all the more remarkable given the amount of mob money stuffed into many other sports during this decade. Now Hartnett and Capone had tracked dirty-looking feet across his nice, clean game.

Landis had nothing to say to Capone, of course, but he quickly got in touch with Hartnett. There is some ambiguity in the record as to whether they spoke in person or exchanged telegrams, but Hartnett defended himself by saying he’d sign for anybody’s kid, including Al Capone’s. Landis was unmoved, leading to the key exchange:

Landis: Hartnett, henceforth you are to have no more contact with Al Capone or any other unsavory character while you are on the field and in uniform.

Hartnett: Fine by me, Judge, but if you don’t want me to have my picture taken with Al Capone, you have to tell him that.

Hartnett had a point. He and the other players were on the wrong end of the power dynamic in this situation. If Al Capone or someone like him wanted an autograph or a picture, any player who valued their structural integrity was going to be accommodating.

Landis understood that banning or otherwise singling Capone out wouldn’t do, either. Capone was still free while awaiting trial, and he’d bought a ticket and done nothing wrong inside the park. And even if he had, baseball wasn’t going to pick a fight with the Chicago Outfit.

But the hoary commissioner had another card to play, the perfect solution for almost any problem: collective punishment.

As the 1932 season opened, both leagues announced that they were reinforcing a long-standing anti-fraternization policy, which forbade players in uniform from conversing with spectators in the stands and/or posing for photographs, starting one hour before the game and for its duration. The policy was nearly as old as the National League, a measure to keep gamblers away from the players, but it was widely ignored and seen as toothless.

Now, violators would be subject to an automatic $5 fine, and an umpire would show up to the park early to handle enforcement. The league presidents were the ones who announced the change, and though they refused to explain what had motivated it, the commissioner’s brutalist fingerprints were unmistakable.

After explaining that the Hartnett/Capone affair was surely the reason for the change, one commentator concluded: “The rule will doubtless bring about confusing situations, but its aim is worthy.” The confusing situations came immediately. Not all spectators were created equal, but the rule did not discriminate, putting players in an impossible position, as the garrulous Rabbit Maranville of the Boston Braves explained that April:

That new rule–no talking to friends in the stands, no talking to rival ball players, no anything friendly and pleasant anymore–is getting my goat. Just think, I walk over to the stands and say “Hello” to my wife, I get a $5 fine slapped on me. And can you imagine what would happen if I didn’t say hello?

Al Capone had spent the fall of 1931 believing that there was a plea deal in place and acting accordingly. Over those months, the judge overseeing his case, James Wilkerson, read leak after leak from Capone’s camp, assuring journalists that he would serve hardly any time in prison. The day of reckoning came on October 6. Capone pled guilty and waited for his short sentence to be handed down. But the furious judge had decided to improvise. As he prepared to rule on the plea agreement, Wilkerson said he was concerned that the gangster seemed to think he was still in charge.

“It is time,” Wilkerson said, “for somebody to impress upon this defendant that it is utterly impossible to bargain with a federal court.” The judge blew up the deal.

According to one court insider, Wilkerson had been stung by Capone’s “unbelievable arrogance” over the previous year, pointing to his “being photographed with prominent baseball players and going so far as to attend the Nebraska-Northwestern football game” as acts of pure hubris.

Essentially forced to go to trial, on October 17, 1931, Capone was found guilty of five counts of tax evasion, and a week later, Wilkerson handed down a meaty 11-year sentence. In effect, the gangster had received 2.5 years for tax evasion, 0 years for racketeering and murder, and 8.5 years because young Sonny Capone wanted to meet his hero and somebody took a picture.

In early May of 1932, Al Capone was finally shipped out via train to the Atlanta U.S. Penitentiary, accompanied by as many reporters as guards and other prisoners.

In what passed as a philosophical moment, he told reporters that “a person must make the best of things, including a long term in prison.” Remorse and foreboding, he said, “led to either insanity or suicide, and I’m not ready for either one.”

And in the spirit of making the best of things, he asked about sport opportunities at the penitentiary. Told there were team sports, including baseball (the recreation yard even had a ball field), Capone brightened. As the press were ushered out of his car, he shouted a parting comment.

Tell the baseball boys down there that Al Capone is one sweet pitcher, and that it won’t be long before we have a team organized that’ll beat anything you have to offer. Organization is my middle name.

Two weeks after Capone went inside the walls, the National League announced they were relaxing the fraternization rule.

The NL president, John Heydler, said, “The rule proved unpopular with the public and press as well as those engaged in playing the game.”

The timing was surely coincidental.

After his father died in 1947, Sonny Capone took up a few different unremarkable vocations and lived a long life as an anonymous, law-abiding citizen. He changed name and left his father’s world, but we really wonder if he kept that baseball…

We’ll be back next week with a tale of cheating and psychological warfare in 1973, starring the Hall of Fame pitcher who mastered both.

On November 18: “The Doctor”

In modern parlance, this is what’s known as “a raspberry.”

Jack McGurn’s real name was Vincenzo Gibaldi. Before finding his calling in murders and executions, teenage Vincenzo had aspired to be a boxer. He chose his nom de guerre because Irish fighters often had better luck getting bookings. When he changed jobs, the name stuck.

Great bit of history - thanks much! My dad was a Chi-town resident at the time, as well as a Northwestern student and a part-time PA for WGN. Wish I could’ve refreshed his recollections by running this one by him.

Paul, you have nicely woven Chicago sports history with its criminal history, making for interesting reading. Can we expect a story about John Dillinger's sporadic visits to Wrigley Field? Thanks! Ron J.