That Kind of Game - Part 1 of 2

In the heat of an unexpected division race in 1974, the Yankees and Red Sox remembered how to be rivals.

In our last story, we made an error—definitely the first time that’s happened.

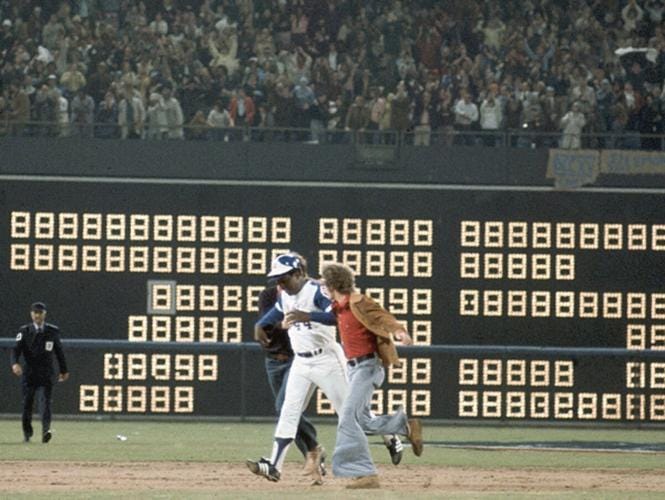

The problem started small. In a passing anecdote we mentioned that New York Yankees infielder Chris Chambliss nearly got hit by a dart thrown out of the stands as he stood at third base at Fenway Park in Boston.

This really did happen, but we garbled the details, including Chambliss’ position and the year. A careful reader noticed the former garble and alerted us in the comments. Their correction inspired us to find out more about what happened in the game in question, and what we found was immediately Project 3.18’s next story. It was a Chaos Game.

While no two are alike, a Chaos Game achieves proper-noun status by containing the following:

At least one ejection

The threat of forfeit (but only the threat; true forfeits are their own thing)

One or more things “that could never happen today”

Fan activity; typically disruption

Umpires having to explain their actions after the game

An abrupt or exciting ending (bonus points for a walk-off or an outcome that hinges on an umpire conference)

Confusion—this might be the essential ingredient.

Confusion is uncommon in baseball, isn’t it? The individual beats of the game are too familiar, spaced out, and legible. Take, for example, a close play at the plate, easily recognizable to any casual fan. The runner is trying to score, the defense is trying to prevent that by tagging the runner, and the outcome may come down to what the home plate umpire sees (or doesn’t see). Reasonable parties may disagree with the umpire’s decision, but everyone understands what he’s ruling on.

But what if, instead of making the call, the umpire does nothing? What if he just stands there? Or what if, instead of trying to score, the runner coming home abruptly turns and runs into the dugout? That’s not what’s supposed to happen; that’s confusion, and nothing sours a baseball crowd quicker. The players get grumpy. And confused coaches and managers usually just start screaming.

These are games those in attendance will never forget, keeping their ticket stub to prove they were there. If you’ve been to a Chaos Game, you’re still telling people about it, and you always will be, even long after you’ve been asked to please stop. Don’t you dare stop.

That’s the kind of game we have here, darts and all, but first we have to set the scene. The early 1970s were something of an awkward phase in baseball’s long history. It was a time of big changes and big feelings throughout the country, the sport, and especially in the city of New York. You see, in the early 1970s, the New York Yankees were not good at all.

It was a season of disruption. 1974 was the year Lou Brock shattered Maury Wills’ single-season stolen base record; and the year Hank Aaron took over for Babe Ruth, becoming the new career home run king and north star of greatness. Previous generations had prized the number 714. Future ones would treasure 755.

But these moments were gems poking out from a trash heap of escalating fan rowdiness, capped off by Cleveland’s Ten Cent Beer Night forfeit in June, the riotous centerpiece in a season of streaking, mooning, hit-and-run smooching, and thrown projectiles of varying densities. And there was real ugliness, too; Aaron’s march toward Ruth’s record drew vicious racist acrimony and even threats of harm.

America was disillusioned and destabilized in the early 1970s. There was recession, fuel crises, lasting damage from the just-ended Vietnam War, and a president who, despite his assurances to the contrary, seemed like he might be a crook.

Only in these, the strangest of times, could the mighty New York Yankees be a sad-sack franchise.

When New York won the 1964 pennant, it was the team’s 29th flag in 44 years, but the run-to-end-all-runs ended there. A World Series loss to the St. Louis Cardinals followed. After five straight first-place finishes between 1960 and 1964, the 1965 Yankees finished in sixth place. The 1966 Yankees finished dead last, something that hadn’t happened since 1912, when “Yankees” was a fresh handle the New York Highlanders were still trying out.

The CBS corporation purchased what it thought was a perennial contender (and revenue machine) in 1966, but all of a sudden the Yankees were neither. Mickey Mantle retired in 1968, and piece by piece the dynasty crumbled.

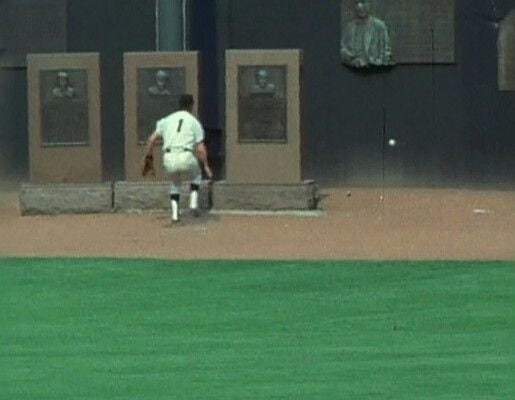

The Yankees briefly came up for air with a second-place finish in 1970 but otherwise they hovered in the bottom-half of their division, wandering amid old plaques and trophies and literally tripping over Yankee ghosts in the outfield. By 1974, only 32-year-old pitcher Mel Stottlemyre remained to tell his young teammates what it felt like to win a pennant for the Yankees.

The Yankees began refloating their sunken yacht with a 1972 trade for reliever Sparky Lyle. Lyle was on the cusp of creating the standard for the modern closer and would become the first reliever to ever win a Cy Young award (in 1977). But even better, Lyle was filched from Boston, the Yankees’ AL East rival and a much better overall team in the first half of the decade. Had Boston opted to hold onto Lyle, the curse of the Bambino might have ended much sooner than it did.

Shipping magnate George Steinbrenner acquired the Yankees in 1973 and promised big things, but before free agency there was simply no way to speed-run a rebuild. In 1974, the team on the field was largely the same one that finished in fourth place the year before.

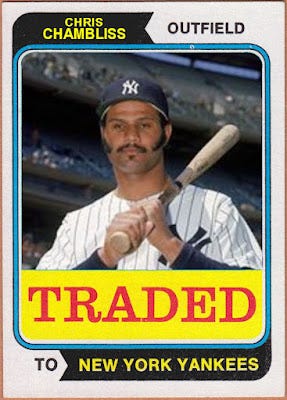

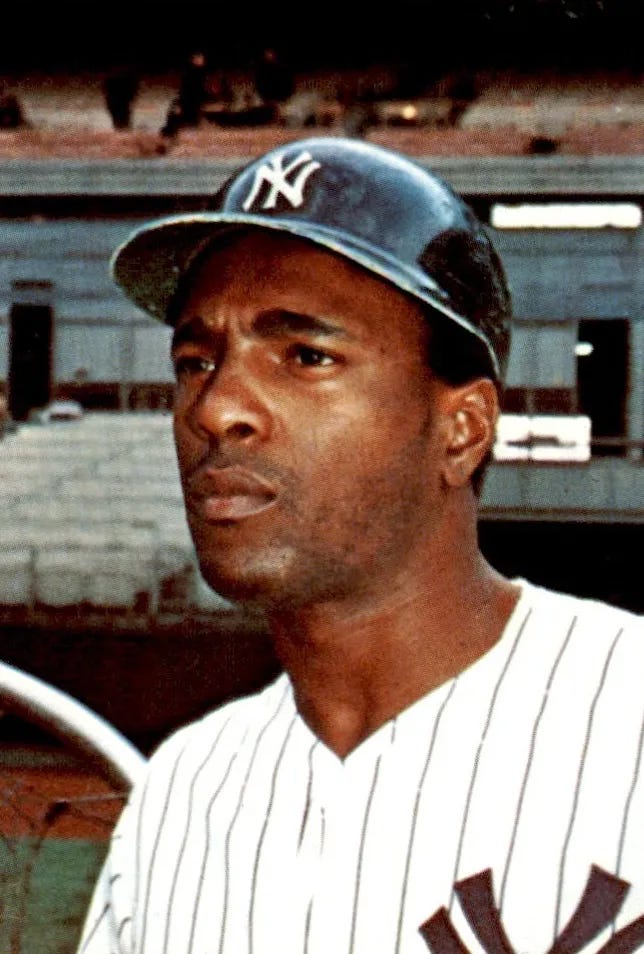

So limited were the Yankees’ options that their big trade chip that offseason was pitcher Fritz Peterson, one of two New York pitchers who’d made the worst kind of news in 1973 by publicly swapping wives. In April 1974 the team traded Peterson and three other pitchers to the Cleveland Indians for a package headlined by 25-year-old Chris Chambliss, a former Rookie of the Year first baseman in 1970 who had struggled to put all the pieces together.

There were a few future champions on the Yankees’ roster. Thurman Munson was established behind the plate and Graig Nettles was locked in at third, but overall, assessing the Yankees’ 1974 lineup, one writer saw too many perplexing disappointments.

Leading off: “Who’s that?

Clean-up: “I thought he quit baseball.”

At designated hitter: “Where did they even dig him up?”

Backup first-basemen Bill Sudakis dubbed his 1974 Yankees “the renegades.” It wasn't entirely clear what the team was collectively rebelling against—perhaps it was conventional wisdom. The pitching was good, at least.

In Boston, the Red Sox had run out to an early division lead and held it for months, but as the summer went on the team stopped hitting and the Baltimore Orioles surged. As these two anticipated contenders went back and forth in the second half of the season, the unassuming Yankees grew ever larger in their rearview mirror.

As summer turned to fall a three-way race materialized in the AL East. On September 4, 1974 the New York Yankees touched first place. Nobody knew what to make of it, least of all the Yankees.

“You know when it really gets down to the nitty gritty, do I know how this team will react?” outfielder Bobby Murcer asked (rhetorically).

Let’s say it’s late September and we’re still there. And we’re all really jacked up to win the thing. None of us has been there before. How will we handle it? It can go either way. Maybe we’ll be so jacked up out of our minds that we don’t feel the pressure and we won’t even know how to fold.

But maybe we’ll go the other way and collapse. I just don’t know.

Nobody did.

After a blowout loss to Detroit on September 8, Murcer hobbled out of the trainer’s room on crutches, playing up a foul tip he’d hit off his foot in the first inning. “Looks like you guys are going to have to do it without me this week,” the veteran announced. “I don’t want anybody blaming me if you blow this thing in Boston.”

The outfielder was kidding—mostly.

His teammate, outfielder Lou Piniella, agreed that the Yankees were in an uncomfortable position. “Two weeks ago, when we were seven games out, I would have given my left arm to be tied for first going to Boston. But now I’d feel a lot better if we had a two-game lead.”

The Yankees’ loss and a Red Sox win against the Milwaukee Brewers gave the two clubs identical 74-65 records. Piniella would have both of his arms for the series with Boston, but the two old rivals would start that series tied atop the American League East.

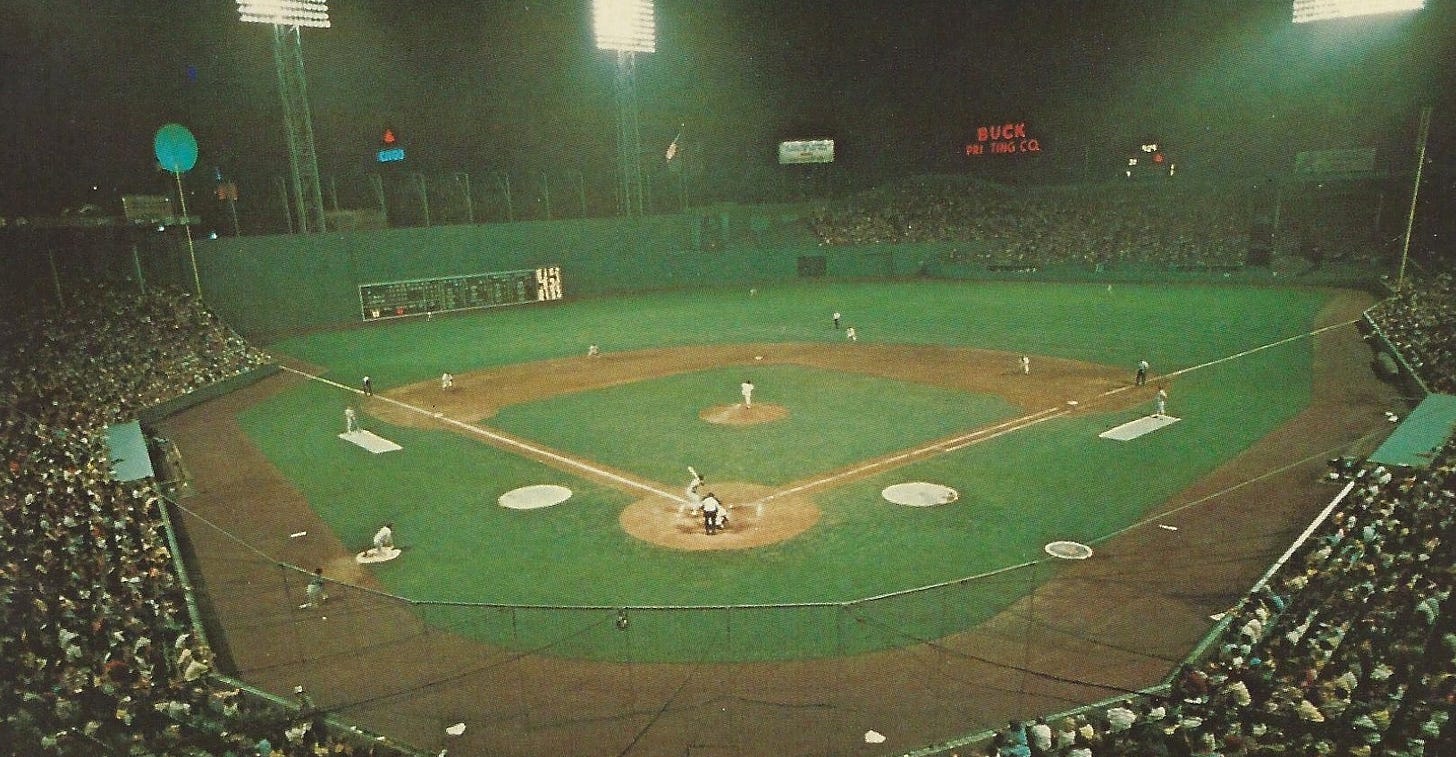

Murcer’s mock-injury had everything to do with the venue for the showdown. The Yankees couldn’t win at Fenway. This was practically a given in 1974. Long before anyone talked about the Babe’s curse on Boston, the Yankees were the hexed club, “haunted by the Monster of Fenway.”

New York had not won under that fearsome wall since July 31, 1973. A longer look showed just that one Fenway win in the Yankees’ previous 22 attempts. In 1974 the Yankees were 0-for-the-season in Boston, and their last attempt had been especially disappointing. The upstart Yankees arrived for a July series at Fenway just a game behind first-place Boston. They departed four games back and were duly written off as a nice story. And yet, here they were again, confronting another statement series.

“The last time we had this opportunity we fell right back on our butts,” Lou Piniella said. “It can’t happen again. It won’t happen again.”

Piniella admitted the losing streak had even gotten under his leathery hide. “It's just a little bit scary. This team hasn’t played good ball in that park for two years and it has to scare you a little to be playing two real important games up there.”

But the Yankees had some reason for hope: the Red Sox were in the middle of a major choke.

After controlling first place all summer long, Boston had lost 9 of their last 11 games and opened the door wide for other challengers. The carnage was such that even the quick-witted announcer Bob Uecker, moonlighting as a national sports commentator, couldn’t bear to go for laughs:

There’s really nothing funny about what’s happening to the Red Sox. At least I can’t think of anything to laugh about. It’s just a case of a lot of young kids on the team busting their hump to do the right thing, to get something started. And the harder they try the worse it gets.

When the Red Sox beat the Brewers at Fenway on September 9 and snapped an eight-game losing streak, a typically sarcastic Boston writer described the scene:

As more than 25,000 lovers of the occult sat in Fenway Park, the corpse sat up and breathed.

“Anyone who doesn’t respect this team doesn’t have respect for anyone,” said veteran third baseman Rico Petrocelli. “We’ve battled back all year, and we’ll keep on battling until this thing is over.”

And while the Yankees were worried, Petrocelli and the Red Sox weren’t about to underestimate them or give undue attention to their winning streak against New York at home. “We have to play baseball and fight. We’re not the 1927 Yankees, you know.”

In the series opener, the Yankees faced lefty Rogelio Moret, a hot hand at the back of the Red Sox’ rotation with a 5-1 career record against New York. The Yankees’ troubles with lefties were nearly as bad as their problems at Fenway, and many were surprised when Bill Virdon, the Yankees’ manager, put the scuffling left-handed Chris Chambliss in the lineup against Moret. Virdon gave an honest explanation. Chambliss was in there “because I haven’t seen anybody else do any better.”

Buoyed by the confidence of his manager, Chris Chambliss hit his sixth home run of the season that night and drove in another with a single.

Starter Doc Medich pitched 7 ⅔ innings before Boston’s Carl Yastrzemski chased him with a home run, but New York was still up by three. That would be plenty for Sparky Lyle, late of Boston, who polished off the Yankees’ win. Virdon was pleased. “I knew we’d win a game here some day.”

One Boston writer marveled at Virdon’s managerial feat, saying, “the job he’s done with this group, he should be manager of the decade.” The Yankees were now alone in first place.

Splitting the two-game series would have preserved the tie atop the division, and given their recent troubles at Fenway, the Yankees would have been delighted just preserving the status quo. All the more so since their game one victory had been at the expense of the Red Sox’ fourth starter. Now the top-heavy Boston rotation was turning over and Luis Tiant was coming up.

No one liked facing Luis Tiant in 1974. The herky-jerky master of a thousand pitches would finish the year with 22 victories and a 2.92 ERA. But it was worse for the Yankees. Not once that year, on the road or at home, had New York managed to beat Tiant. How many futility streaks could they really expect to end in just two games?

But in winning the first game, New York had breached the fortress walls. Another win, and they’d have the two-game lead of which they’d dreamed.

“This is the way I like it,” Roy White said, “Play the teams you have to beat to win. Either you put them behind you or you can forget about it for another year.”

White had joined the team in 1965, meaning he’d had to do a lot of forgetting. No other living man had played nine seasons in pinstripes without ever reaching the postseason. To White, the sensation of controlling one’s destiny was a rare treat, one he savored.

“It’s all right there, laying on a plate,” he said. “Waiting to be taken.”

The Yankees’ general manager, Tal Smith, had a green light to do whatever he could to put the team over the top, but there weren’t many options so late in the season. Nonetheless, as the team prepared for the pivotal series with Boston, Smith was busy checking every dusty closet of the American League for anything that looked like a competitive edge. On September 9 he found something—a particularly edgy player named Alex Johnson.

That day, the Texas Rangers had conceded another season to the three-peating Oakland A’s and began shedding dead weight. Among the castoffs was Johnson, an aging gap-hitter who had not been a fit in the Rangers’ clubhouse—or any clubhouse, actually.

Johnson’s eventful career and complex attitude toward baseball is worth more time than we can give it here, but suffice to say he was introverted to the point of being antisocial and frequently criticized for “unhurried” play, a rap he barely protested. “I try,” he said, “in my way.”

It is not surprising that things didn’t work out for him in Texas, where he had long been benched by the Rangers’ perpetually simmering manager, Billy Martin. While both men were moody and brooding, Martin and Johnson’s styles and philosophies were so antithetical it is a wonder they never came to blows.

Hoping to hustle Johnson out of town before Billy got around to taking a swing at him, the Rangers put him on clearance, available for the bottom-dollar waiver price of $20,000 (but absolutely no exchanges or refunds).

Still, there was just one taker: the New York Yankees. An extra bat for the stretch run couldn’t hurt, and Johnson, sporting a .291 average in 114 appearances, was a professional hitter if not much else.

The Rangers were in California when Johnson was traded, and he was sent east to join up with his new team. He did not arrive in Boston until after 2 AM, and 12 hours later he was sitting in front of his new locker, his No. 54 (a number so high it would make spring training invitee wince) jersey hanging behind him as he answered reporters’ questions in his signature style:

How did he really feel about reporters?

I like them. I don’t know if they should like themselves. I try to go to church as often as I can. Otherwise I wouldn’t like them. I’ll cooperate as long as there’s no bull. When it comes down to a lot of bull, that’s when I might call you a name.

Did he have problems with Billy Martin?

I didn’t trade myself. I just jumped on a plane and came here.

Why did he think [several of his new Yankee teammates] had said he’d be a big help to the club?

I don’t know, but they’re entitled to their opinion.

Did he regard any fellow players as close friends?

No.

How did he feel about wearing No. 54 for the New York Yankees?

It makes no difference which number I wear. I’ve had a lot of them. I’ve played with a lot of the Yankees, now I hope I can help them win.

Okay, but, c’mon Alex, it’s the Yankees.

I’m out there to win the money; it’s not the uniform.

In his 13-year career, Alex Johnson played for eight different teams, never for more than two seasons. You can really see why.

Asked what he thought of hitting at Fenway, the right-handed Johnson reminded reporters that he was not a home run hitter (he’d hit just four that season) and stated that as far as he could recall none of his 70 career home runs had come at Fenway. A good contact-hitter, Johnson was truly elite at managing the others’ expectations.

The veteran had no illusions about his role on the Yankees. A weapon of last resort, he’d sit alone at the end of the bench and wait for what meager scraps of chance might come his way. He had a surprisingly constructive thought about that.

“This team was in first place when I got here,” he told reporters. “I just hope I can do something to help.”

Hours later, at the end of a long, turbulent night at Fenway Park, the newest, oddest Yankee would get his one and only chance.

Next week we’ll get right into the action and see how many criteria this particular Chaos Game checks. (Hint: all of them.)

On July 28: “‘A Bounce Out’”

Being born & actually living on Broadway & 191st. Street in Washington Heights I lived about 8 miles from Yankee Stadium although my Father never took me there I was 7 when we left for Bergen Cty., NJ I do remember watching them on WPIX channel 11 watching Mickey & listening to the Scooter - Phil Rizzuto.

And yes, I remember those monuments in center field watching guys chasing balls behind them. Never made sense to me but I did question to myself why all parks weren’t in fact the same. After all records were kept on all kinds of statistics; how fair was that when everyone’s parks were different?

Such is the mind of a child!

I guess the only constant in life is change. Now bases are larger, catchers are framing the ball (cheating), pitchers hands are in their mouths, sliding gloves are used & we have ghost runners to end the game sooner. Didn’t we pay to watch a game, so now we’re there we need to leave sooner? Do you hear my Andy Rooney impersonation?

And yes, I grew up ‘hating’ Red Sox fans although I’ve spoken to many at the Stadium. Someone ask them why their song Sweet Caroline was written by a Brooklyn guy. Maybe they don’t know Brooklyn is in NY?? Now where did I pahk my cah?

Early 70’s were “an awkward phase in baseball’s long history,” I think the early 70’s were an awkward phase in general. All the things you mentioned pretty well sum it up. I never knew there was such a thing in baseball as a ‘Chaos Game.’ Paul, I have a question: what makes the ‘Green Monster’ so insurmountable? Is there any other ballpark that has as challenging a wall in the outfield? Also, I enjoyed listening to your friend, Josh, call his first MLB game.