(Now That's What I Call A) Forfeit

The word “forfeit” seems to come to us from Latin by way of French, having roots in “foris” (outside) and “facere” (doing). In the context of sport, it connotes a “loss through transgression,” as opposed to a loss through performance. Broadly, being unready or unable to play as agreed/expected may result in a forfeit, or one may be assigned as a sanction or punishment in response to specific misconduct or negligence by one team (or both).

Forfeiting a game is the purest form of losing, because it does not require another team to even beat you. It is, in many ways, the competitive equivalent of walking into a closed screen door. It is also one of the few outcomes to a game that can be imposed by a third party for subjective reasons, making a forfeit both anti-competitive and, in theory, anti-entertaining, at least for any fans present who came to see an actual game. Reading about them later, however, can be highly entertaining, as we will see.

Most of the major team sport organizations in America have given the forfeit a wide berth. The National Football League allows games to be forfeited if a required minimum of players are not present and ready to play, but Pete Rozelle, the sport’s most influential commissioner, manifested a historical precedent when he vowed never to use the rule. The National Hockey League similarly allows for the possibility of forfeits, but none have been recorded that we could find. The National Basketball Association mentions forfeiture as a possible sanction in response to the worst misbehavior, but no such penalty has ever been imposed, even in occasions where it may have been warranted.

In modern times, forfeitures have become so vanishingly rare that to get hit with one would itself be a major story and would only compound whatever negative press was already coming from whatever events prompted it. For this reason, the forfeit remains largely in its original packaging, on a high, dusty shelf, in every major league save one:

NFL: 104 years in operation. Recorded forfeits, 1, maybe? Basically zero.

NBA: 78 years in operation. Recorded forfeits, zero.

NHL: 107 years in operation. Recorded forfeits, (amazingly) zero.

MLB: 148 years in operation, Recorded forfeits, 135.

Baseball’s forfeit rule has not received much recent use, but across the game’s long history, you can see that it has been thoroughly broken-in.

The above numbers are back-of-the-napkin depending how you want to count things, but serve to show that only in baseball have forfeited contests made up a measurable (if still small) chunk of the record, and many of these games-gone-awry fit right in here at Project 3.18.

The best overall research we have seen on indexing professional baseball’s forfeits has been done by historian Gary Frownfelter, who, along with a cadre of supporting baseball researchers, has painstakingly excavated and preserved details on forfeits, work you can find at retrosheet.org. Frownfelter has recorded instances of professional forfeitures as far back as 1871, pre-dating the founding of the National League, and his records also include several predecessor leagues and offshoot leagues but, we should point out, do not as of yet attempt to address the Negro Leagues. Looking at forfeits in the Negro Leagues would be fascinating, but for our purposes today, we’ll be citing the history of baseball’s forfeits as documented in Frownfelter’s existing work.

Broadly speaking, Frownfelter et. al. have documented around 135 official forfeits recorded since 1871, but looking at the timeline, we see two different stories here:

Before 1901 (29 years): 97 recorded forfeits

1901 - 2024 (123 years): 38 recorded forfeits

Our use of 1900/01 as a cutoff stems from the fact that many baseball scholars use it that way, as it is the point when the game’s rules had mostly settled into those still used today, allowing easier historic comparison. As we can see, more than two-thirds of baseball’s forfeits pre-date this maturity.

These lost games highlight the growing pains of baseball’s infancy and youth, as a lack of established systems and controls resulted in more frequent failures. Even the “mature” forfeits are heavily front-loaded: more than half of them, 20 out of 38, occurred between 1901 and 1910.

If we break baseball’s 16 decades into rough thirds, it becomes even clearer that forfeits were a “childhood malady”1 of baseball, or a symptom of a malady, at least, and that first third in particular has the sepia-tones we’re looking for in this section of Project 3.18:

1871 - 1929: 122 forfeits

1930 - 1979: 9 forfeits

1980 - Present Day: 1 forfeit

In their comprehensive accounting of lost games, Frownfelter and his colleagues strive to provide a few sentences of detail on the cause of the forfeit, when they have found any. Trying to concisely capture some of baseball’s most confusing and disorderly moments in a neutral paragraph is a bit like trying to raise piranhas in a goldfish bowl, and just as interesting to look at.

Reading their work, two different classes of forfeits present. The first are of the straightforward kind that merit little if any unpacking. A paragraph will do, in these cases, which Frownfelter has ably provided. Let’s look at just a few of them to get the idea and talk about why many forfeits happened.

No Game Today

As we noted is the case across North American sports, baseball’s early forfeit rules were intended to address some expected logistical concerns. A game could not be played if both teams weren’t present and ready to go, and in the occasional instances when one team was present but the other not (or if a team left inappropriately), umpires were to award credit for the game to the club who’d been ready to play as scheduled.

The early frequency of these logistical-type forfeits reflects the game’s nearness to its amateur club roots. For a sport already drawing tens of thousands of spectators per game, 19th Century front offices were still small-to-nonexistent and sometimes important details got lost. As a result, teams missed trains, forgot which city they were supposed to travel to, and were occasionally uncertain whether and when there was to be a game at all. Quoting Frownfelter:

“05/31/1888 - Pittsburgh at New York - NL - Pittsburgh did not appear for the game. They later claimed that they telephoned the Polo Grounds and were told that the game had been canceled. New York was awarded the game.”

“Well, we’re leaving!”

There was a great deal of collective pouting in early baseball. Many forfeits centered on rules-based disputes, typically between one team and the umpire, resulting in the objecting team refusing to resume play or leaving the grounds altogether. In these scenarios, the umpire was to award the game to the other team via forfeit:

“07/23/1901 - Washington at Cleveland - AL - Washington led 4-3 going into the bottom of the ninth, then Jack O'Brien walked, was singled to second by Erve Beck, and then scored all the way from second when Candy LaChance beat out a bunt. Bill Coughlin and Bill Clingman both called for the ball to be thrown to third, claiming that O'Brien had taken a shortcut via the pitcher's box in order to score, and when Umpire Tommy Connolly refused to uphold the protest, team captain Bill Clarke pulled Washington off the field, causing the game to be forfeited to Cleveland.”

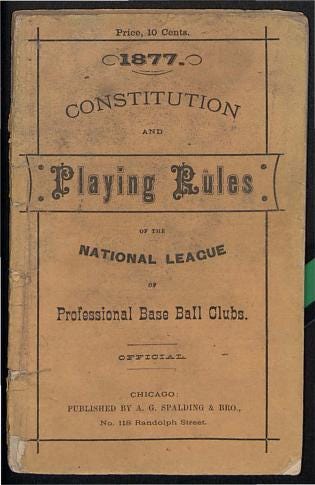

In later decades, it became trendier for unhappy players to antagonize the officials until they were individually thrown out, but in the early days, some of the more high-minded malcontents opted to simply sit down themselves, or even depart. Baseball’s official rules had addressed such behavior from the sport’s earliest days of national organization. From the Constitution of the National League of Professional Baseball Clubs (1877):

“When the umpire calls “play,” the game must at once be proceeded with. Should either party fail to take their appointed positions in the game, or to commence play as requested, the umpire shall, at the expiration of fifteen minutes, declare the game forfeited by the nine that refuses to play.”

Embracing the Darkness

When the games were played at uncovered ballparks without electricity, let alone overhead lights, weather and daylight became levers by which a team could try to gain an advantage. Umpires could and would penalize teams with a forfeit when these efforts became too unsubtle:

“09/22/1892 - Chicago at Pittsburgh - NL - In the middle of the fourth inning with Pittsburgh leading 9 to 2, Chicago started delaying the game hoping for a rain out. Umpire John Gaffney called the game a forfeit for the home team.”

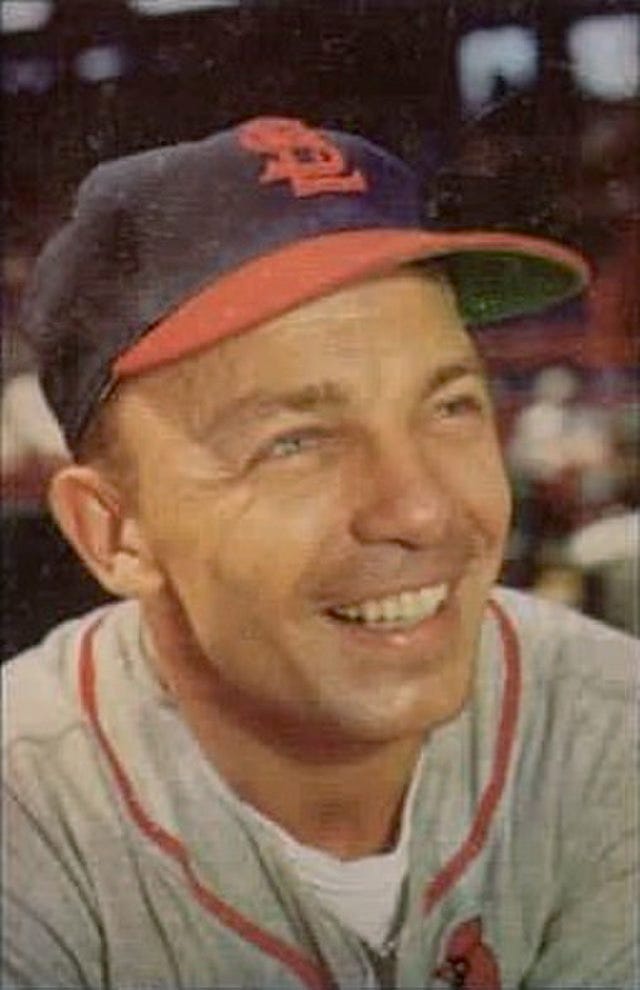

Light-related gamesmanship was still happening as late as 1954, when the only forfeit in a twenty-year span involved a manager, the Philadelphia Phillies’ Eddie Stanky, waiting out the daylight at Sportsman’s Park/Busch Stadium during the second game of a double-header. Stanky hoped to see the game called on account of darkness but wasn’t discreet enough about it–he kept changing pitchers even as they succeeded in collecting outs, and the officials decided he was stalling and gave the game to the Cardinals. Baseball’s improved schedule planning bureaucracy and the onset of stadium lights had eliminated this scenario for decades, but an earlier eighty-minute rain delay made the tactic viable2 one final time.

“The Beast” Got It

One more mundane example we nonetheless enjoyed (there are several of this variety):

“07/27/1890 - Columbus at Brooklyn - AA - Columbus was awarded the game when Brooklyn could not furnish a new ball after the old one was hit out of the grounds. The game was in the eighth inning with Brooklyn leading 18 to 8.”

The Best of the Worst

In other cases3, Frownfelter’s restrained summaries leave much to the imagination and invite more questions of why than they have space with which to answer:

“04/23/1892 - Louisville at Chicago - NL - The game started out in sunny warm weather, but by the 9th inning it was a raw cold day. Chicago was leading 4 to 2 when the crowd poured onto the field.”

Why does a change in the weather bring the crowd out of their seats and onto the field in the ninth inning with the home team leading and about to win?

“07/20/1918 - Cleveland at Philadelphia - AL - The second game of a doubleheader was awarded to the Cleveland Indians. With Cleveland leading in the ninth inning, 9 to 1, a barrage of seat cushions poured out of the stands onto the field. The fans in the lower levels ran out onto the field to escape the cushions raining down on them. A few employees tried to clear the field, but could not.”

Why did the upper-level fans start throwing their cushions, and at whom were they throwing? The fans, the umpire, the team? Who are these brave employees that tried to restore order without any assistance from the authorities?

“09/26/1942 - Boston at New York - NL - In the second game of a doubleheader with the score 5-2 in favor of the Giants, hundreds of children swarmed onto the field after the final out of the 8th inning. The children were the guests of the Giants as part of a promotion. They had brought scrap metal to the game for the war effort.”

What was the promotion? Why were these children singled out as the cause of the disturbance? Where were their parents? Were they still holding the scrap metal at this point? Because hundreds of children rampaging across a baseball diamond while brandishing pieces of scrap metal during a wartime supply drive is so Project 3.18.

In our “Now That’s What I Call a Forfeit" stories, we visit many of the game’s meatiest forfeits, each of them a time capsule packed with strong characters, period charm, and subplots galore. We explore why baseball failed on that particular day, and what that failure tells us about the team, the sport, and the times.

For variety’s sake, when we feature a forfeit, we won’t do so in chronological order, and they’ll be written with any necessary information and historical context provided. We may visit the 1880s and then jump ahead to the 1940s.

Where we’ll never go, in this series, at least, are the 1960s, 1980s, or the 21st Century, because those eras were or thus far remain forfeit-free. Should modern baseball return to its roots with a forfeited game, rest assured it will receive thorough-bordering-on-obsessive coverage in this space.

In much the same way, might we imagine steroids and other performance-enhancing drugs as a disease of baseball’s middle-age? We’ll make a note for a possible future think-piece, but feel free to go ahead and run with it, if you are interested. We have 135 forfeits to get through.

As far as we can tell, Busch Stadium first hosted a night game in 1940, and so it is unclear why darkness was an issue at all fourteen years later. Why weren’t the lights on? Why did Stanky think he could make the night his ally any place other than Wrigley Field?

These are still among the tamer examples of the genre–we do not wish to spoil many of the great stories we’ll be investigating in this series. We are definitely going to cover the one with scrap-metal-wielding children, though.