The Days of Whine and Cork - Part 2 of 2

Pay no attention to that power surge behind the curtain!

We’re back with a few more stories from the Mets’ and Cardinals’ brushfire rivalry in the mid 1980s.

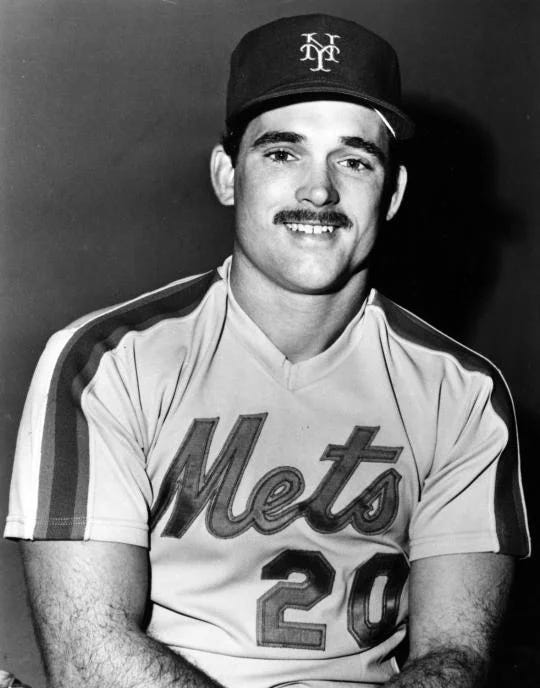

The 1987 schedule-makers must have known St. Louis would need a cooling-off period after sweeping the Mets in April, and in their wisdom they arranged things so that the Mets did not return to Busch Stadium until late July. By then, the Cardinals had a six-game lead in the NL East standings, but the joke was about to be on J.C. Corcoran, because “pond scum” (algae) thrives in warm, humid environments. The Mets won on July 28 and July 29 by a 6-4 score. The big blow in the second game was a 10th inning home run by a surging Howard Johnson.

The Mets’ third baseman was 26 and in the middle of breaking out into a power hitter—power he would consistently flash over the course of his ensuing peak years. But in July 1987, Whitey Herzog didn’t have that perspective, and when it came to the Mets, he saw (or imagined) only the worst.

Johnson was on a short list of players that the Cardinals suspected were altering their bats: opening them, drilling them out, and “corking” them with either soft spongy wood or rubber. Such bats were, of course, illegal, but any time a player was caught using one, it would come out that his team kept a few around, “for fun,” to be used in batting practice and other non-game activities. And, would you believe it, some players (very foolishly!) stored these pieces of contraband in the same racks where they kept their regular bats, and, gosh, sometimes a fun bat would “accidentally” make it into a game.

“I had a guy using a corked bat once and I didn’t even know it,” Herzog said in one of several discussions on illegal bats he’d have that season. “He was hitting home runs all over the place, and then the cork fell out.”

Howard Johnson’s power surge made him St. Louis’ Most Wanted. After Johnson’s 10th-inning home run on July 29, the Cardinals’ manager began an investigation. He tried to get ahold of the bat Johnson used to hit that home run, but “the batboy grabbed it before it hit the ground,” raising the manager’s suspicions even further. He resolved to be ready the next time Johnson struck, and he did not have to wait long.

As much as Cardinal fans looked down on the Mets from their first-place perch, losing to the Mets naturally made things worse. Wearing a Mets Keith Hernandez t-shirt to Busch Stadium was an act of real bravery that summer. If you made it that far. One fan visiting from New York for the late July series recalled that wearing such a shirt earned him a sharp rebuke from the front-desk agent at his downtown hotel.

Things had escalated to the point that (according to the Post-Dispatch) the Cardinals’ general manager, Dal Maxvill, quietly reached out to J.C. Corcoran to ask the DJ to “cool it” with his Pond Scum campaign, and from what we can tell he seems to have done so. Unfortunately, by July 30, the teams were ready to supply the necessary vitriol themselves.

Going into the final game of the series, the Busch Stadium crowd was in a foul mood. Facing a sweep and a halving of their team’s first-place lead, they took their feelings out on the Mets’ starter, Dwight Gooden. Gooden had missed the April series at Busch as he was participating in a drug rehabilitation program, and throughout his July start, the crowds chanted “Just Say No,” a reference to the ubiquitous Reagan-era drug-prevention campaign slogan. Other Mets who’d had substance-related run-ins got personalized chants of their own.

Gooden tuned out the noise, pitching eight strong innings, allowing three runs, and striking out six. Meanwhile, Howard Johnson stayed hot, hitting a solo home run in the eighth inning, off of St. Louis reliever Bill Dawley. It was his 25th of the year.

As the Mets’ third baseman circled the bases, the team bat boy picked up Johnson’s discarded bat, an Adirondack model made of unfinished wood, 34.5 inches long and weighing 31.5 ounces. Straightening up, the bat boy was confronted by the Cardinals’ catcher, Tony Peña, who took the bat out of his hands. As Johnson finished his circuit, he found Peña giving his bat a thorough inspection and tried to put a stop to it.

“It looked funny to me,” Peña said. “You can hear the sound of the bat. That sounded phony to me. I wanted the bat checked. For some reason, he (Johnson) didn’t want to have it checked. Why?” To stop the kids from fighting over their toy, Joe West, the home plate umpire, confiscated it and put it high up in the proverbial closet.

“Basically, Joe took the bat because it looked like the players were going to get into a fight over it.” the crew chief, Paul Runge, said.

The Mets finished off the game, winning 5-3 and earning a series sweep, but rather than celebrate, they closed their clubhouse to the press until the umpires returned Johnson’s bat. Runge and his colleagues performed their own visual inspection and, seeing no signs of foul play, gave it back. They did not cut it open, Runge explained. “Joe saw nothing wrong with it and we have no way of keeping it because as far as we’re concerned, it’s not illegal.”

“I wanted to get the one from last night,” Herzog said afterward. “[Johnson] looks like Babe Ruth, and I know he ain’t that good.”

For Herzog, this was far from case-closed. Afterward, he imprecisely claimed he had “acquired” one of Johnson’s bats from the first game of the series, had it X-rayed, and found it had been altered. But, as far as we can tell, the offending bat was acquired surreptitiously/extrajudicially and had to be returned, leaving Herzog resolved to get another one.

“I got an X-ray on [one] bat, and it [was] corked,” Herzog insisted.

There’s really no doubt in my mind. Howard really tried to get it back [tonight], didn’t he? I wish I would have had a hatchet. I don’t know what would have happened to me, but I would have cut it open. I know it was corked. He’s not the only one over there using corked bats.

Herzog left it at that, but elsewhere, Red Schoendienst, then a coach for the Cardinals, named names, including the Mets’ second baseman, Wally Backman, who was colorfully nonplussed to hear it.

“Why don’t they just have a guy piss in a cup every time he hits a home run?” Backman said in response to hearing his name had come up. “Howard could have hit that pitch out with a Wiffle Ball bat. If they tried to do that with my bat, I would have grabbed it back and smoked somebody with it.”

To Johnson himself, all this talk of cheating ignored the basic application the principle of Occam’s Razor: “It was a fastball down the middle,” the exasperated hitter said.

What am I supposed to do with it? I’m known as a dead fastball hitter. Ask Dawley. Ask Peña where the pitch was. Herzog is being disrespectful to me and my ability. Why not check Jack Clark’s bats; he’s never hit this many home runs. Check Eric Davis. Kirby Puckett. Don Mattingly. It’s a joke.

Keith Hernandez, who knew Herzog the best, suggested his old manager might not even need to believe the Mets were cheating to see benefit in making accusations. “It’s a reach. Maybe Whitey’s trying to rattle us.”

People weren’t yet in the habit of plastering one unimaginative suffix on any type of public controversy, but Herzog’s “Cork-gate” set off a league-wide set of accusations and recriminations, mostly focusing on the Mets. Johnson continued to hit home runs, and nearly every manager he encountered wanted his bat investigated. After one testy exchange in Houston, Johnson hit a home run and gave the Astros dugout a free sample. “I threw the bat over toward their dugout. I was trying to give them the bat and say ‘Hey, if you want it, cut it open right there.’” It got so bad that on August 7, MLB instituted a new rule giving managers the right to request the umpires check one (and only one) bat per game.

The Mets’ third baseman had mostly accepted his new reality. After his bat was confiscated for the second time since the rule went live, he seemed very Zen: “If it’s all right, which it is, I’ll get it back. It doesn’t bother me if they want to X-ray my bat, as long as I get it back in one piece.” His bats were checked at least six times, and no bat was ever found to have been altered. Johnson began playing full time in 1987 and also entered what are typically a baseball player’s peak-performance years. He hit 36 home runs that season and hit 23 or more home runs in each season until 1992. By the time he finished his career, he had the third-most home runs of any Met at the time. The guy got good, but in the heat of rivalry, nobody in St. Louis wanted to see it that way, especially Herzog.

Later, in a swing through Montreal, the Mets left a piece of evidence behind in the visitors clubhouse, to be discovered by the Cardinals, who were following them into town. Arriving at Stade Olympique, the Cardinals found a bat with a few dozen bottle corks glued to it. Johnson denied involvement.

A lack of any evidence would barely dent Jack Clark’s conviction that those mid-eighties Mets were a bunch of cheaters. The keystone slugger of the Whiteyball Cardinals was as confident in 2009 as he’d been 20 years earlier, even when a reporter informed him that Johnson had never actually been caught using a corked bat.

“That just goes to show those guys were trying to cheat and you know, it didn’t end up working for them anyhow,” he said, but he quickly pivoted to an accusation harder to disprove: Those Mets were showboats, particularly that Gary Carter.

“He talked his way more into the Hall of Fame than deserving it.” Not true.

Clark said he took offense with the way Carter “craved the spotlight,” which was “pretty sickening and disgusting to everyone else.” Even in taciturn baseball, this strikes us as a rather confusing line of attack. In 1987, a professional sports star in the country’s largest media market was supposed to avoid recognition and attention? Even John Updike had given up on the virtues of stoicism by the 1980s—gods may not have answered letters, but now you could fax them.

On August 1, 1987, the sports editor for the Post-Dispatch, Kevin Horrigan, used his column to ask all Cardinals fans to “cool it.” The hostility toward players like Johnson and Carter had grown ridiculous. “If Gary Carter played here, people would love him.”

And while Shea had once held the worst fans in the National League, Horrigan pointed out that the only time fan behavior stopped play between the Mets and Cardinals that season was at Busch, during Seat Cushion Night.

“It’s as if some people out there were taking lessons and morals from the Bleacher Bums in Chicago. I take that back. [The Bums] were not into self-promotion. They knew baseball.”1

“The Cardinals don’t hate the Mets,” Horrigan went on. “They resented some of the attention the Mets got in 1985 and 1986,” and sure, maybe they suffered from typically-Midwestern insecurity complexes when compared to flashy East Coast rivals.

Decades later, Clark insisted that the animosity was very real, at least for his part. In his 2009 interview, he said that he detested the Mets so much he would ignore them even when they were teammates during the All-Star Games of that era.

“I wanted to let them know I wasn’t glad to be there with them and their teammates, didn’t want to be on any team or be a teammate with them, and we were going to battle.”

The battles of 1987 were pitched, and when they ended, the Cardinals stood victorious, making it all the way to the World Series before falling to the Minnesota Twins in seven games. St. Louis won the NL East by three games, which means that the April series sweep, largely courtesy of Tommy Herr, constituted the difference. Were he so inclined, Gary Carter could have looked back and fairly said that that April sweep ended the Mets’ hopes for the 1987 season, but, alas, his book had already come out.

The Mets would take their turn winning in the division in 1988, but then the rivalry was put on hiatus as both teams fell out of contention. In 1994, it was canceled entirely, as the league realigned and the Cardinals, arm-in-arm with their ancient rivals, the Chicago Cubs, departed for the newly-created Central Division, leaving room for the Western-exiled Braves to rejoin the East, just in time to rule it for a generation.

As early as 1994, the Post-Dispatch found itself having to remind readers of what once was. Bernie Miklasz marveled at how quickly it had all gone away: “Remember the old days of whine and cork?” he asked his readers.

The Mets are in town, and no one cares. They could just as well be the Padres, Astros, or any other generic brand of baseball. Once upon a time the crass Mets … embodied the New York vanity and arrogance. But now Los Angeles has surpassed it to become the nation’s most pathetic, dysfunctional city. New Yorkers can no longer take pride in being the most miserable citizens in America.

Evan Corcoran had long given it up: “The people who inspired all of this hatred are all gone,” he said.

“The rivalry is dead.”

Project 3.18 certainly hopes the rivalry is not dead. Maybe it’s just sleeping.

Do you have memories from when the Cardinals and Mets were at each other's throats?

Do you have a Pond Scum t-shirt in your closet, or know someone who might?

Any photos of Busch Stadium II in that era?

Share some stories and details with us, in the comments below or by sending us an email at project318@substack.com, and we’ll help share them with everyone.

As we mentioned last time, next week has been circled on our calendar for quite a while: It’s the 50th Anniversary of Cleveland’s Ten Cent Beer Night!

We’ve got some great stuff planned. We’re going to partner with northeast Ohio baseball fans this time—and a visiting expert.

We’ll send out a little Programming Note on Sunday night to get things started—see you then.

And thus did Horrigan reveal that he did not really know the Bleacher Bums, who were so into self-promotion that they had a PR Director.

Great part 2! I am fascinated by these backstories and intend to upgrade my subscription later in the year when I can end another.

Off the topic, Paul, but I read this yesterday: https://www.mlb.com/news/stats-leaderboard-changes-negro-leagues-mlb I’m sure you’re aware. (I sent this as a comment on the part 1 episode but I was two days late reading it so you might not have seen it.)

Very apt portrayal of what happened in 1987. I recall there also being talk about there being rubber balls inside of HoJo's bat. Johnson may have been in the head of Whitey Herzog but as was the case in 1985 and 1987 the Cardinals had the last word over the Mets. And left handed reliever Ken Dayley was a thorn in the Met's side except for the shot off the clock by Darryl Strawberry in late 1985 before Johnson joined the team. Straw will have his number retired at Citi Field on Saturday.