The National Bird of Canada - Part 1 of 2

On-field accident or international incident?

Last week we covered the various “in-game” bird incidents in baseball history, most of which took their turn in the news cycle and then disappeared. We couldn’t help but notice that almost every report of each of those events—in 1984, 1987, and even 2001—referenced the same prior incident, the 1983 godfather of baseball bird stories, involving Yankees slugger Dave Winfield, an international road-trip, and a ring-billed gull that should have moved.

This is that story.

The Leslie Street Spit extends about five kilometers1 into Lake Ontario off of Leslie Street, in Toronto’s east end. Looking at it today, it reminds us a little bit of a bird in flight (or, we think, a pterosaur), but if you looked at the same spot in the 1950s, you’d see nothing, because the Spit is entirely man-made, the result of a large public works project to create a protective breakwater for Toronto’s Outer Harbor.

Beginning in 1959, Toronto built the Spit with debris from construction projects throughout the city. As old row homes and commercial buildings were demolished to make room for modern office buildings, tons of old bricks and other material ended up in the Spit. But when the Outer Harbor never developed as a shipping hub, there was no longer any need to commercially develop the newly-created land, though it continued to be used for landfill throughout the 20th century. With no infrastructure present to support people and no real reason for humans to be there, the city offered no public access to the Spit. As late as 1973, you couldn’t reach it unless you had a boat…or wings.

Canadian naturalists have designated the Leslie Street Spit as an “Important Bird Area.” 300 species of birds have been identified on the Spit, with 45 species keeping breeding/nesting grounds there, including herons, cormorants, terns, swans, owls, and gulls.2

Because many gulls do not want to nest in areas of significant vegetation, the newly-created Spit quickly became a seabirds’ paradise. Birds soon moved in and secured the site for generations that would follow. By 1983, tens of thousands of gulls made their home at the site, including an estimated 6% of all the ring-billed gulls in the world.

About nine kilometers west of the Spit, past the Inner Harbour area and the CN Tower stabbing at the sky, sits what is today BMO Field, an outdoor stadium for several different versions of football. The field sits roughly two parking lots from the edge of Lake Ontario. For a bird, it’s an exceedingly-easy commute.

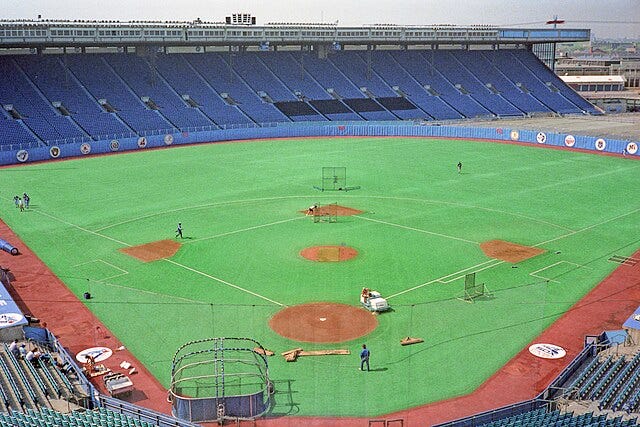

In 1983, a different stadium stood on that site: Exhibition Stadium, first home of the Toronto Blue Jays. The stadium began its life as a Canadian football facility but was reconfigured to support baseball as a part of the successful 1977 effort to receive an MLB expansion franchise.

Exhibition Stadium and baseball were an awkward match. According to the first president of the Blue Jays, Paul Beeston, not only was Exhibition Stadium the worst ballpark in baseball, it was the worst stadium in sports. Many of the seats were poorly-situated for watching baseball, and the team had no choice but to close them off unless the Jays made the playoffs. Plus, the spring weather in Toronto could be a tad biblical.

While Toronto is actually further south than parts of many American states (and all of North Dakota) its position on Lake Ontario makes springtime in the region an exercise in wishful thinking. The first Jays’ home opener was played on snowpack. A game in 1984 was canceled due to winds so strong pitchers couldn’t stay on the mound. Evening fogs settled in so thickly that fly balls dropped in the outfield unseen.

And there were the birds, mostly gulls, many visiting from the nearby Spit. The Spit gulls came in numbers, bringing large appetites and little fear of humans. The closed-off outfield sections left plenty of room for the birds to visit and safely congregate during baseball games, and they tended to use the grandstands as a restaurant and the playing field as a spot to nap.

One regular ticketholder in 1983 described the “menace” gulls had become to sporting events at the Ex:

“The gulls would glide in and attempt to snatch popcorn from us at every chance. If a hot dog bun dropped between the seats, dozens of crazed gulls would dive in to devour every morsel in sight.”

In early August, 1983, the New York Yankees were in town for a four-game series with the Blue Jays. It had thus far not been a fun visit for the Yankees, who had lost the first three games. August 4 seemed like a better opportunity, for the team and for center fielder Dave Winfield, who singled in a run in the first and doubled in another run in the third. It was a warm, foggy night, and dozens of gulls wheeled idly around the field, occasionally alighting on the outfield turf to rest.

By the fifth inning, the score was 3-1. As the Yankees took the field on defense, Winfield warmed up his arm by playing catch with left fielder Don Baylor. When they were finished, Winfield threw the baseball towards the right field foul line, where a bat boy named Jeff Pinchuk stood near the Yankees’ bullpen, waiting to collect it, as was standard practice.

At this point, accounts begin to differ. All agree that there was a ring-billed gull sitting somewhere in the vicinity of the right field foul lines, but some have it perched on a fence, while most accounts, including Winfield’s, place it on the turf. All agree that Winfield threw the ball, but how he threw it and where he aimed are in dispute. The resulting throw traveled about 80 paces and missed the batboy by quite a lot. The errant ball bounced on the springy playing surface and smacked into the unsuspecting gull.

“Pow!” said Jeff Torborg, the pitching coach, who was in the nearby Yankees bullpen. “Right in the head. The bird went pffft.”

After a brief period of indecision, Pinchuk retrieved a towel from the dugout and came to remove the gull. A disbelieving Winfield stood in center field and watched with his hands spread palms out in front of him, at one point putting his cap over his heart.

Toronto Police Constable Wayne Hartery saw the whole thing. The off-duty officer was working a security shift near the right field bullpen. In 2013, he told the Toronto Star what he thought had transpired:

Every inning up until this inning, Winfield would get the ball and throw it into the ball boy sitting beside me. That ball would roll into that ballboy at about one mile an hour, there was just enough heat on that ball to make it, and on this inning, and I can’t prove what he said, but he turned [Baylor], when he picked up the ball, and again I can’t prove it, but I know he said, “Watch this,” and he turned with everything he had, and he threw that ball.

At the time and in 2013, Winfield maintained it had been an accident:

When I finished playing catch, I was throwing it to the ballboy, they sit down the right field line. I saw the bird in that direction. I threw in that direction, but really not anticipating or expecting to hit it. I threw it with some force to get to the ballboy, sure enough the bird, you know, it just killed it immediately.

“That bird didn’t look right to begin with,” Torborg said after the game. Didn’t you see how its feet sort of skidded out underneath when it landed?”

Both Hartery and Torborg, the pitching coach, stated that the bird’s behavior had been somewhat unusual in that it had not moved for several innings.

Winfield had noticed this as well, saying in 2013: “It was on the ground, it had been there for a while between innings…”

He then offered a revealing summation:

Honestly I would have thought like anything else, sometimes birds scatter as an object comes toward them, whether it’s a car or a baseball…I would kind of liken it to, if you’re driving down the street and you see a squirrel or raccoon or something and you’re driving pretty quickly and you say, “Ah it will move,” and you hear the thump and you say, “Oh man,” and that’s kind of the way it unfolded, I didn’t expect to hit it, but I did.

Of course, we weren’t there, but this is Project 3.18, and you know we are going to render a judgment on this. This accident, unlike those we profiled last time, was not a freak occurrence. It was foreseeable and preventable if certain choices were made, but Winfield didn’t make them. Having examined all the evidence we could find, the pertinent facts seem to be these:

Winfield was aware that he was throwing into the vicinity of a gull which had been stationary in the same spot for several innings

There is no concrete evidence he intended to hit the gull, but, by his own admission, he failed take any extra care with his throw, putting the burden on the bird to move out of the way

Our verdict: involuntary manslaughter…unless it could somehow be shown that something was wrong with the bird...

The game was being broadcast on local television and radio, and hundreds of thousands of potential bird-lovers saw or heard what happened. Many of them began calling those same radio and television stations, as well as the Toronto police.

“It is my understanding that a lot of people took this incident very seriously,” a police spokesman said. These people had a surprising champion in Constable Wayne Hartery. In his judgment, the Yankees’ center fielder had just committed a crime, and he was in a unique position to do something about it.

The game resumed, but Winfield received an ovation of boos. Hartery remembered that the 30,000 fans in attendance kept a “Winfield sucks” chant up for the better part of the next four innings. Some fans who happened to have rubber balls on their person tried to turn the tables by hurling these in the outfielder’s direction.

“The fans got on my case pretty bad,” Winfield said. “They always pick out the big guy.”

In his playing years, Winfield was 6 feet, six inches tall and 240 pounds. In the apt words of sportswriter Jim Murray, he looked like “40 home runs and 100 runs batted in waiting to happen,” holding a bat that looked like “a conductor’s wand” in his hands. There was no question who the little guy was in this conflict, and it was not the human.

Winfield thought he understood why the fans were so upset. He hadn’t killed just any bird. “It was unfortunate about the bird, but also unintentional. I’m just sorry the national bird of Canada no longer exists.”

The problem was, Canada did not have a national bird in 1983. Gaffes like this are why the crisis public-relations field exists today.

The game ended with a 3-1 New York win. Winfield walked into the clubhouse and was greeted by the mocking boos of his teammates and cries of “murderer!” He was changing when Billy Martin, the Yankees’ manager, told him he had visitors waiting outside. It was Constable Hartery and other plainclothes police officers. They took Winfield to a private room and informed that he was being detained under Section 4.02, subsection 1A of the Canadian Criminal Code: causing unnecessary cruelty to an animal, punishable by a $500 fine and up to six months in jail.

Word of what was happening made it to the Blue Jays, and president Beeston and general manager Pat Gillick arrived on the scene to try and smooth things over, but Hartery wasn’t having it. He was taking the player to jail. Winfield finished dressing and said goodbye to his teammates. “See you in six months,” he said. The remark was intended as a joke, but after the unlikely events of the night thus far, who could rule it out?

Here’s the conclusion:

This is a Canada story, so distances are in metric units and certain proper-noun spellings will be weird. Sorry.

The term “seagull” is apparently just a catchall term any bird from the entire Laridae family, which includes 54 different species of gulls. The specific bird you or I recognize as a “seagull” differs depending on where we live. In Toronto, any bird referred to as a “seagull” is likely to be a ring-billed gull.

Well told Paul. I have a recollection that later on Yankee manager Billy Martin when asked about the incident quipped that he knew Winfield could not have been intentionally throwing at the seagull =

'He hasn't hit the cutoff man all year'.

Paul, I don’t remember this incident although I thought he hit a bird on the fly as he threw home from the outfield. Maybe that was someone else??? I’ll hafta Google it. Thanx I did enjoy your writing