The Year of the Squirrel

The postseason is full of strange champions, but in 2011 St. Louis went on a run with a commonplace critter.

Last week we wrote about wildlife in the postseason, but the fauna involved—midges the size of nickels—produced a story that was, we confess, a bit icky.

This week we decided to write about a more benevolent ballpark intruder, one which made “impromptu waves” in St. Louis, Missouri in 2011.

On October 4, 2011, in the sixth inning of the third game in the National League Division Series, a squirrel was spotted on the field at Busch Stadium.

The Cardinals’ Ryan Theriot was batting when the it first appeared, scampering in foul territory along the third base line. The game was briefly delayed until the animal vanished under the rain tarp rolled up in left field. The game participants had a collective shrug, Theriot singled, Jon Jay walked, and the Cardinals’ pitcher, Jaime Garcia, struck out to end the inning.

During the delay an imaginative Philadelphia writer had wondered if the squirrel might be an ill omen, harkening back to the most famous ill omen in baseball, 1969’s black cat at Shea Stadium. But the Cardinals rally had fizzled and Philadelphia actually won the game, 3-2. If this was a jinx, it wasn’t a very good one. The squirrel wasn’t a harbinger, the writer decided, it was merely lost; and the Phillies’ win sent it “back to obscurity.”

But this was 2011, in the golden age of Twitter, where minerals, vegetables, and certainly animals of public interest were routinely anthropomorphized and given a voice. It was just a question of who would do it and how quickly. That same night “Busch Squirrel” began tweeting and soon had a few thousand followers. Obscurity had been canceled.

The Phillies now had a 2-1 lead in the best-of-five series most people expected them to win. They were a beastly team in 2011, a slugging powerhouse with a pair of aces, Roy Halladay and Cliff Lee. They’d won 102 regular season games and handily taken their division. In this playoff format, their top record gave them the honor of facing the wild card entrant.

Across the diamond, the 2011 Cardinals were the definition of surprise. As late as August they had no chance of winning the NL Central and were at one point 10.5 games behind the wild card-leading Atlanta Braves. But the Cardinals went 18-8 in September. So deep was their hole that this still wouldn’t have been enough, except the Braves went 9-18. Even then, the Cardinals were fighting for their playoff spot on the very last day of the season, when a St. Louis win and a separate Braves loss vaulted them into the playoffs.

After losing on October 4, St. Louis was facing elimination. Roy Oswalt, the increasingly crafty veteran at the back of the Phillies’ rotation, was tabbed to finish them off. The Cardinals were down early, but by the fifth inning they had come back and held a 3-2 lead on the strength of a 2-run double by third baseman David Freese.

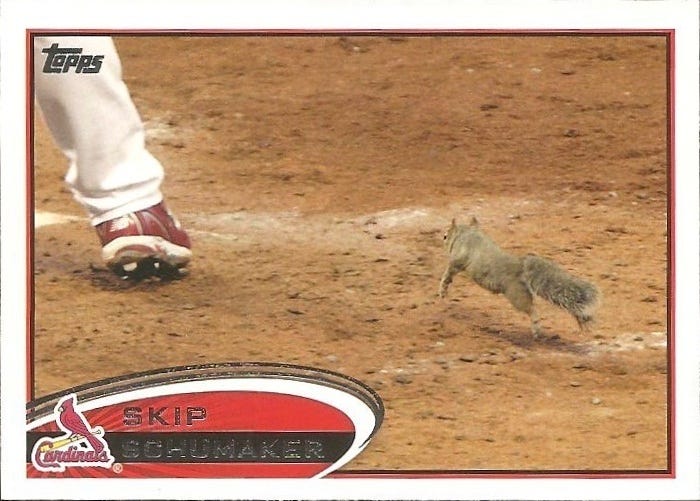

With one out and no one on base, Oswalt prepared to pitch to Skip Schumaker, the Cardinals’ second baseman. As he prepared to throw, Oswalt spotted a small flash of something furry and gray streaking from left to right through the batter’s box. He might have stopped his wind-up, but feared a balk call.

“I didn’t want to stop in the middle of my motion, so I threw it,” he said. The pitch went nowhere near the strike zone and Schumaker, having also noticed the ground-level missile, was not swinging anyway.

The animal had also been spotted before the game, frolicking in the grassy area beyond the center field wall, but now it was front and center and on national television. At least five separate camera operators had angles on the squirrel as it darted past Schumaker’s legs, and TBS showed them all to a national audience as commentators offered one “nut” pun after another as the footage rolled.

The squirrel vaulted over a low wall and into the grandstand, sparking what one observer aptly described as “an impromptu wave” as fans leaped out of their seats when it passed underfoot. The same account reported the intruder “was last seen under a nacho bar outside section 150,” which was either great journalism or completely made up.

Meanwhile, Oswalt pled his case to home plate umpire Ángel Hernández, arguing that the squirrel had distracted him during his throw. He wanted a do-over, but Hernández resisted and Charlie Manuel, the Phillies’ manager, soon joined the conversation.

“If it ran up the guy’s leg, what, are they going to call it a strike?” Oswalt asked after the game. “I was wondering what size animal it needed to be for it not to be a pitch.”

Oswalt’s “squirrel ball” ultimately did nothing for the Cardinals. Schumacher flied out, as did Albert Pujols behind him, and Oswalt worked a clean inning, the last one he’d have that year before David Freese did his Superman thing and hit a two-run home run for St. Louis in the sixth, essentially putting the game away.

The squirrel, meanwhile, was live-tweeting its follow-up performance and racking up thousands more followers every hour. It wasn’t particularly witty, as online rodents went, but one response showed some gumption. Charlie Manuel was asked about the squirrel and expressed regret he hadn’t been armed at the time. “Being from the South, and being a squirrel hunter, if I had a gun there, might have done something. I’m a pretty good shot.”

On Twitter, Busch Squirrel was having none of this: “Charlie Manuel is too old to shoot me or have a gun.”

“Busch Squirrel” was a perfectly apt name for St. Louis’ newest folk hero, but it didn’t last. By October 6 and especially October 7 it had been publicly rebranded as the “Rally Squirrel,” despite having played no part in a comeback. The Cardinals were losing when it first appeared and subsequently lost. They were winning during its second appearance and went on to win. The lazy1 moniker probably originated somewhere online but soon it was everywhere.

And while Charlie Manuel threatened to shoot it, the Cardinals’ manager, Tony La Russa, as grim-faced and taciturn a personality as baseball had to offer at the time, seemed quite charmed by Rally Squirrel and the enthusiasm it had generated. After his team tied the series at two games apiece La Russa was asked about the squirrel, and boy did he have a response ready.

Just a bit of context here—the Cardinals’ utility infielder, Allen Craig, was known to have a pet tortoise (named Torty; who also had a Twitter account). Anyway, Tony, tell us about this squirrel:

My understanding is that the squirrel was the tortoise’s pass to the game, and they’re supposed to be here tomorrow together, and I don’t know if the tortoise took a walk and the squirrel panicked. I don’t know the rest of the story but I think that the squirrel is attached to Craig’s tortoise and I’m expecting them to be here tomorrow. Maybe they have a suite so they won’t be running on the field. I’ve never met it. I actually want to meet the tortoise. The squirrel, too.

October 6 was a travel day, giving the legend of the Rally Squirrel a few hours to grow while staff at Busch Stadium confronted a problematic situation. They estimated that two or three squirrels were living inside the ballpark.

“We understand there’s a little bit of levity involved,” a park official said, ”but we also look at it as a public safety issue. We don’t want our fans having problems with them. And we certainly don’t like anything that interrupts the play on the field.”

The team set out seven humane cage traps baited with peanut butter. Adorably, a trail of ballpark peanuts was set out to lure any curious critters inside the trap.

And this brings us to what is, by far, the strangest part of this story, and, we must say, an underemphasized bit of the lore.

On October 7 the decisive fifth game of the series was played in Philadelphia, at Citizens Bank Park. Citizen’s Bank Park is a remarkably straight shot east from Busch Stadium, but the two ballparks are still 889 miles apart. And yet, when the Phillies got home to take care of business, the squirrel was waiting for them.

Before game 5, a squirrel was found prowling the warning track of Citizens Bank Park. The squirrel seemed to target…Roy Oswalt, getting so close that Oswalt (unwisely, we feel) made a stab at the squirrel with his glove like it was a chopper up the middle and not a small packet of muscle, claws, and buck teeth.

What went through the Phillies’ heads as this animal ran past their feet? One squirrel is a shrug, two is a coincidence, but a third, on the other side of the country? That’s stalking.

Oswalt wasn’t able to grab the squirrel but apparently it was caught, “by a member of the grounds crew.” And we have so many questions about how a single person with no foreknowledge managed to capture a squirrel in the vastness of an empty ballpark, but these details are lost to history. But if you are or know that Philadelphia groundskeeper, please, be in touch—we’d like to share your story with the world.

The Cardinals won the game, 1-0. Skip Schumaker, blessed by the squirrel in St. Louis, delivered the game-winning RBI double in the top of the first inning and pitcher Chris Carpenter made that hold up, throwing a three-hit shutout.

On October 8, a large adult male eastern gray squirrel was found in one of the cage traps at Busch Stadium. A local nonprofit organization, the Wildlife Rescue Center in Ballwin, Missouri, had already made contact with the Cardinals and volunteered to take any captured squirrels off their hands for a safe relocation in a more suitable habitat.

“He won’t get peanuts and popcorn,” the WRC’s director said. “But he’ll have very healthy food and a great environment.”

No one could be sure if this was the Rally Squirrel, the one that had run past home plate to spoil Roy Oswalt’s pitch, but this guy looked and acted the part. “He had a real attitude and sass.”

The squirrel’s time at the shelter was appropriately brief. After a cursory exam revealed a very healthy subject, he was carried to a wooded path near the center and given his freedom. “He was more than ready to go,” the WRC director said, watching him disappear up a large hickory tree.

At least three more squirrels eventually took the bait at Busch Stadium and, presumably, made the same trip out to the suburbs. However, the actual animals involved had ceased to matter. You can’t humanely relocate an idea, and the Rally Squirrel had become the embodiment of the “screw it, we’re here, aren’t we?” attitude of the 2011 Cardinals.

The team’s marketing team leapt into action as the team began the NLCS on the road against the Milwaukee Brewers, who had handily beat them to win the Central. By the time the series returned to St. Louis, 40,000 “rally towels” with a “squirrel motif” were ready for distribution. Toy squirrels were available in the ballpark store, five or six dollars apiece, twelve if you wanted the one with a squeaker. “Got Squirrel?” shirts were also available.

“I think it’s good,” La Russa said. “The fans are having fun.” Reflecting on how strange that sounded coming from his perpetually scowling countenance, the manager said he really was on the side of hilarity, given the circumstances. “This is not old-school, and I know I am in many ways, but I think there’s so much attention and pressure on the players that sometimes they don’t show happiness.”

The Cardinals defeated the Brewers in six games, and happiness abounded in St. Louis. As did squirrel merchandise.

One costume shop owner reported the squirrel had gone from his worst-selling rodent costume to his best overnight. “We were already carrying the Rally Squirrel,” he said, “we just didn’t know it was a Rally Squirrel.”

A confectionary owner remembered that on a trip to the Netherlands they’d acquired a mold for making squirrel-shaped chocolates. They had tried selling them around Easter but the squirrels puzzled midwestern consumers and the molds went up on a high shelf. Now they came down, the price went up, and St. Louis residents bought dozens every day.

As the Cardinals’ unlikely postseason advance continued, opportunistic merchandisers squeezed the Rally Squirrel as they could. The squirrel was a dream of commodification, being a recognizable and popular a symbol of the team that was entirely lacking trademark protection.

There were some limits—any footage or images of the actual Rally Squirrel (not to mention Skip Schumaker’s feet) were protected, as was the term “World Series,” and all the usual IP depicting the Cardinalis cardinalis. One T-shirt vendor got a cease-and-desist letter for printing “Go Cards” on his squirrel shirt, but the offending text proved unnecessary—a squirrel on a red background sold just as well. The market was open, the fans were near delirious, and more than one entrepreneur shot their shot:

The Cardinals faced the Texas Rangers in the World Series. The Rangers had a better team on paper but they did not have an unstoppable talisman that, according to physics, has no practical terminal velocity. Advantage, St. Louis.

There had been far fewer sightings since the ALDS ended, but Busch Stadium officials were not ready to guarantee that the World Series would be squirrel-free. And so the question was put to the umpires: What would happen if, on baseball’s grandest stage, a baseball hit a squirrel?

“We’re all aware of what could happen,” MLB’s umpire executive, Rich Rieker, said before Game One in St. Louis. He told the inquiring reporter that a ball that hit a squirrel or any other animal would remain “in play.”

Rieker then added, apparently unprompted, that if the Rally Squirrel happened to run up a hitter’s leg, “that would be the umpire’s discretion, in terms of what to call.” But the rodent rules were never tested; the Series went seven games with no sightings, let alone any pant-leg incursions.

The Cardinals won it, of course. Players waved stuffed squirrels during the postgame celebrations. And the franchise did much the same when it commissioned championship rings that honored both mascots.

The broader commercial ownership of the “Rally Squirrel” intellectual property took time to establish. The Cardinals and MLB didn’t weigh in right away, and several vendors tried to earn some credibility by making trademark applications before the big dogs started barking. One of these vendors got ready for the inevitable litigation by claiming that his vision for the Rally Squirrel transcended St. Louis, and even baseball: “We don’t really want to tie it to the Cardinals2. It fits all sports out there.”

Obtaining a trademark, especially one likely to be contested by a heavyweight like MLB, could take more than a year, and one IP lawyer wondered if people were giving too much credit to what was essentially a meme. “In a year and a half is anyone going to care about the Rally Squirrel?”

As civic talismans, squirrels are underrated. There is something defiant and destabilizing about that flash of gray and brown, especially when it appears somewhere it’s not expected. Being in close quarters with a squirrel is a great way to remind us of the true wildness of these urban cohabitants and the minor wonders they are capable of. People may be on top of the food chain, but for the most part squirrels end up looking down on us. The squirrel’s “attitude and sass” was a perfect match for the underappreciated Cardinals when they unexpectedly found themselves in urgent need of a postseason identity.

While none have had anywhere near the sense of timing that the Rally Squirrel did, squirrels continue to make regular visits to our ballparks, capturing our attention and, from a distance, our affection.

On August 21, 2025, a squirrel appeared in the batter’s box at Yankee Stadium. In the top of the fourth inning, the critter ran so close to the feet of the batter, Boston’s Jhostynxon Garcia, that fans almost got to see the “umpire’s discretion” scenario imagined prior to the 2011 World Series.

Instead the squirrel shot up the third base line while the crowd cheered it on. It halted on the pitcher’s mound and locked eyes with New York’s Max Fried.

“My first reaction was, ‘Don’t do anything that might embarrass you,’” Fried said. “I thought it was going to run around, but it came straight to me. At one point, I think I just said, ‘OK, buddy, let’s go.’ He just did his thing.”

From there the squirrel headed for first base, where New York infielder Ben Rice made a rather unceremonious sidestep out of its path.

“I didn’t want to touch that thing,” Rice said. “Now the guys are giving me crap for it—‘Why are you scared of a squirrel?’ I don’t know where that thing’s been. It made a little noise at me.”

For a half-inning or so there were two games to watch. In one the Red Sox and Yankees played, and in the other a squirrel tried to figure out how to exit the field of play. It finally found a chain link fence in front of a digital scoreboard and vanished…but not into obscurity.

Red Sox manager Alex Cora reckoned they hadn’t seen the last of the squirrel: “Somebody’s going to make a T-shirt out of it.”

We couldn’t find the shirt—but we did find the baseball card.

This story isn’t even old enough to drive, so we’d love to hear from any readers with squirrel-related memories from 2011, or 2015, or 2018, or 2019 (Minnesota).

Or share a favorite animal incursion—if we get some good ones we’ll turn it into a future piece!

Project 3.18 is off next week, back on November 10, but we’ll have a new episode of Clear the Field on Thursday.

With that said, if we get an animal on the field during the World Series, expect an emergency edition.

The “Rally” referenced the Rally Monkey, a digital mascot for the Anaheim Angels that went sort of proto-viral during that team’s 2002 World Series run. For many years after (in the same way public scandals were required to end in “-gate”) weird mascots would be labelled “Rally.”

The United States Patent and Trademark Office ultimately disagreed with any claim that the “Rally Squirrel” belonged to the ages, awarding the trademark to a little mom-and-pop operation named “St. Louis Cardinals, LLC.” The house always wins, eventually.

Love the squirrel story, Paul. Of course my favorite squirrels, behind Rockey J. Squirrel, of Rockey & Bullwinkle fame, are the black squirrels, running around on the Kent State campus, in Ohio - they are truly badass.

Hi Paul, I had a vague recollection of the squirrel thing in St. Louis in 2011 but your story was a fun and interesting read. I so wanted there to be a connection to NY Met Jeff McNeil!