The Zoo is Closed - Part 1 of 2

Fed up after a spring of rowdyism, the Detroit Tigers decided to try baseball without any fans in the "cheap seats."

Given our primary research interests, we here at Project 3.18 are well-versed in the ways baseball teams responded to unruly fans over the course of the 20th century. Belatedly adding more security (or any security, for that matter) was a popular tactic, as were public-address reminders and admonishments, first appealing to common decency and then threatening arrest. As a last resort, if things got really out of hand, teams might try a bit of discreet shrinkflation on the ballpark beer cups.

All of these measured responses reflect the underlying difficulty: the people causing the problems were also the people paying the bills. Fans go to baseball games to have fun, and crowd control isn’t fun, unless you are a closed-circuit video enthusiast. Reining in the fans was often a practice of half-hearted compromises.

Until 1980, when a baseball executive in Detroit went full Skynet and concluded that the most logical way to stop crowd trouble was to remove the crowds.

Until it ceased operations in 1999, Tiger Stadium was the oldest ballpark in the major leagues, tied with Fenway Park, which opened on the same day in 1912. When it first opened, Navin Field sat about 23,000 people and would have looked a little more like its jewel-box contemporaries in Boston and Chicago. But over the course of the 1930s, successive owners expanded the park by progressively wrapping a second deck around the outfield, a process that created an enormous center field bleacher section that held a fifth of the seats in the entire park, so big that the first ten feet of it actually hung out over the outfield warning track.

Though they were the cheapest option ($2 apiece in 1980), Tiger Stadium’s bleacher seats defied the usual tropes by offering some of the best views in the park—much better, regulars felt, than those available in the more-expensive grandstands or the much-more-expensive boxes. As a bonus, bleacher seats kept the enormous center field scoreboard (an eyesore, purists felt) out of view.

The views were great and the seats plentiful, but some of the logistics were challenging. The bleacher sections were separated from the rest of the park, which meant anyone buying a bleacher seat could only rely on the limited amenities available in that section: concessions, bathrooms, and alcohol. The Tigers did not permit beer vendors to work in the bleachers themselves, meaning thirsty patrons had to leave their seats and endure long lines, sacrificing several innings of sunshine and frivolity for a watery 14-ounce beer. Lacking convenient options, some fans got creative.

George Puscas, a sportswriter for the Detroit Free Press, was himself a regular in the bleachers, agreeing with many other Detroiters on the appeal of those seats. As an insider, Puscas had close-up access to bleacher culture and explained some of their methods for bringing fun into the ballpark.

In a column that ran on May 31, 1980, he accompanied a bleacher regular to a nearby drug store before the start of that day’s game. Puscas took notes as the man purchased a flat pint of rum and used athletic tape to secure this to the underside of his stomach. “When the guards at the stadium frisk you,” the man explained, “they never touch your belly below the belt. They’d better not.”

Similarly, “if my girlfriend was going with me, it’d be no big deal,” he told Puscas. “She’d just slip the bottle in her underwear.”

Puscas wanted to use his platform to humanize the bleacher crowd after some recent bad press. On May 20, fights volleyed around the center field bleachers all evening, along with the usual beach balls lofted overhead. “You couldn’t pay me enough money to sit in those bleachers, day or night,” one reporter said to his colleague as they watched the spectacle. “Those are real animals out there.”

The trouble reportedly began, as was often the case, with spectators throwing projectiles—bottles and at least one smoke bomb—onto the field, where the Tigers and the visiting New York Yankees were trying to safely do their jobs. The Yankees’ center fielder, Ruppert Jones, stopped play mid-inning to procure a batting helmet to wear on defense—always a bad sign.

Staff from Burns Security, a big security player at ballparks in those days, waded into the seats to find and extract the worst offenders. Depending on which side you asked, either those guards were themselves jeered and pelted with trash, and even attacked, or they came in hot, strong-arming and provoking larger groups of people in their quest to punish a smaller group of instigators.

Such interventions were inevitably doomed, as another Free Press columnist, Jim Fitzgerald, pointed out:

The problem is people have resented authority figures since the invention of fathers, and rent-a-fathers are the worst. In a hassle between a jerk and an authority figure, bystanders always root for the jerk. The farther away from the action they are, the harder the bystanders root.

This, according to Pusca’s inside man, is exactly what had happened on May 20:

The guards come in and try to remove one guy and he won’t go so they start beating the hell out of him. Nobody wants to see that guy get killed, so other guys jump in and then you’ve got a riot.

Over the course of the evening, 12 people were taken to jail and another dozen or so received citations from Detroit police officers. Still more were merely tossed out onto Trumbull Avenue. Two Burns staff members were treated for minor injuries. The Tigers came away with a 12-8 shootout victory over the Yankees, but May 20 would be remembered as “riot night” for the remainder of the season.

The next night, the club responded proportionally. Additional guards and Detroit police were stationed at every point of entry, and the frisking was extra-vigorous. There were only four arrests and one guard got a beer poured on him, making the evening a qualified success.

The city authorities began paying attention. “I don’t want to spoil anybody’s fun,” said Councilman Jack Kelley, “but it’s getting just like a zoo out there in the bleachers. There’s talk about putting up chicken netting like they have behind home plate so those people can’t throw stuff down on the field.”

“I don’t know what the problem is,” said a stadium employee. “Maybe it’s all the people getting laid off.” This was a common refrain. Many people perceived a correlation between Detroit’s hard times and Ruppert Jones’ hard helmet, even if they could never establish a firm cause and effect relationship.

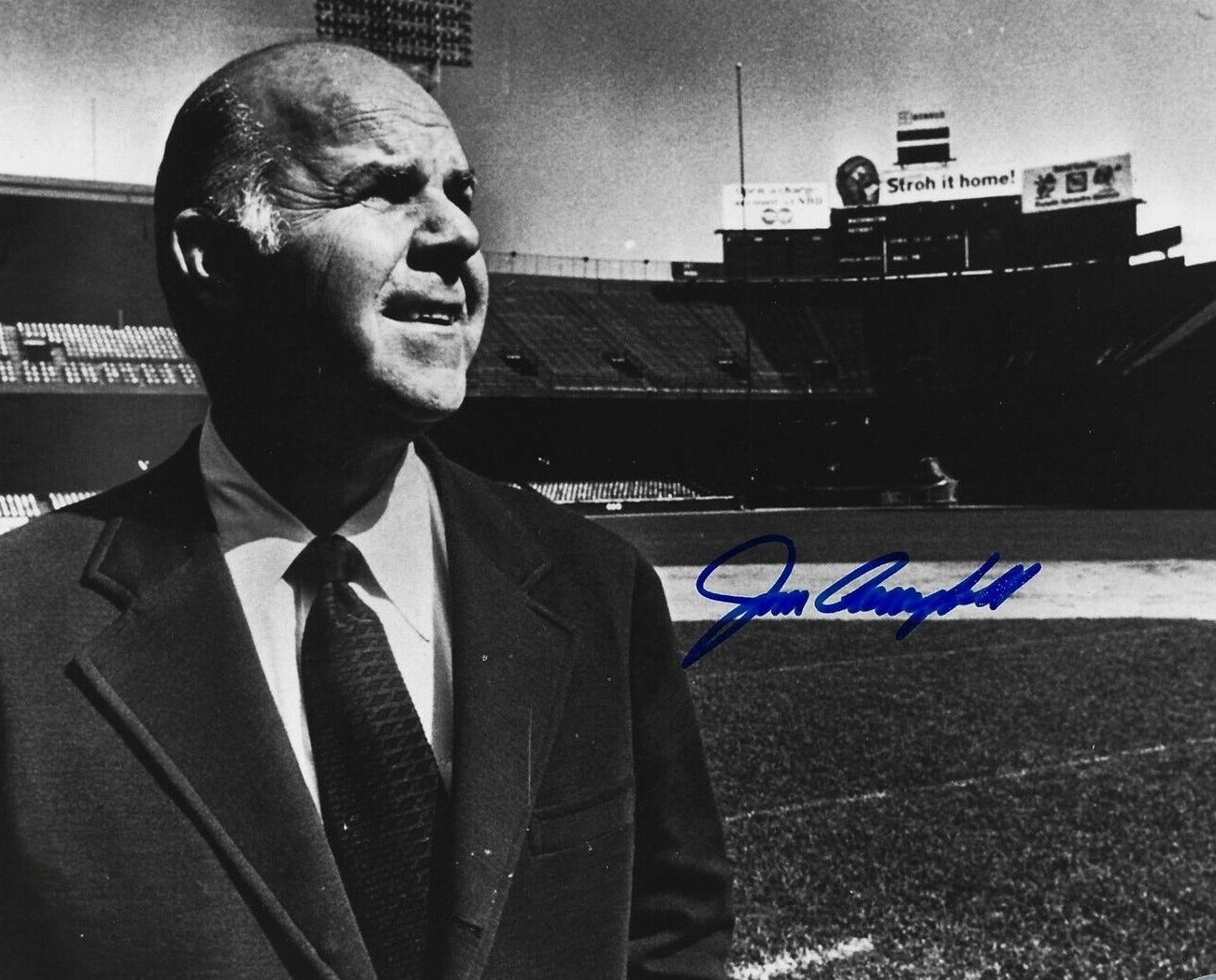

The city councilmen were chirping and the Tigers were parked in last place, but you could hardly tell from talking to Jim Campbell, the president and general manager of the Tigers. Campbell built one World Champion club in 1968 and now was on the verge of assembling another. He had been a part of the organization since 1949, long enough to see Al Kaline as a rookie; Denny McLain and now Mark Fidrych rise and fall; and Billy Martin come and go. At 56, Campbell was the absolute authority regarding all things Tigers. The club spoke with one voice and it was his. Even the owner, John Fetzer, gave his handpicked executive a free hand while he himself kept a low public profile.

In a June 1 feature on Campbell, published just a week or so after “riot night,” the Associated Press lauded him for his accessibility and patience. “He never ducks, he never tries to hide out, and he seldom bares his frustrations in public. His self-control is sometimes astonishing.”

“I sometimes get a little upset, but I try not to explode,” Campbell agreed. This was essential in Detroit, which could be “a volatile town.” The previous December, after he traded fan-favorite Ron LeFlore to Montreal, someone deposited a large load of horse manure outside the administration entrance at Tiger Stadium. Campbell kept his cool.

The Tigers would need more of the same as they looked for creative, considered solutions to the increasing problems out in the bleachers, and Campbell, the article proclaimed, was “the right man, in the right job, in the right place.”

After “riot night,” bleacher-based anthropological studies proliferated in the papers. Jim Fitzgerald, the Free Press columnist, described the problematic bleacher denizen thusly:

The typical Tiger Stadium jerk is a white male, 18 to 35 years old, wearing a tee-shirt full of gut which hangs over his belt. He travels in packs of jerks and is drunk before he gets inside the stadium. He jumps on the field or climbs the foul screen to prove he is a man.

The bleacher crowd was nearly all white at a time when Detroit was roughly a third white, making the bleacher community not a representative slice of the city as a whole, but a world unto itself.

Another columnist, Bob Talbert, sought out some of the regulars he happened to know. These regulars were in their mid-twenties, and starting in their high school years, they’d attended at least 40 Tigers games a season, always in the bleachers.

Talbert’s regulars claimed their crowd behaved, to a degree. “Sure, we drink beer and, sure, we smoke marijuana. We do these things as we do them in our own homes. But we come for baseball, not the high.”

Pusca’s source generally concurred. “It’s not a crowd of drunks. I’d prefer to have a beer or two. I don’t even like rum and Coke,” he claimed, as he finished taping rum to the underside of his gut. The problem, he said, was the stadium policies that made buying bleacher beer such a pain, prompting many people to bring their own, stronger booze and end up over-serving themselves.

The Tigers were in the middle of a ten-year climb from the bottom of the league back to the top. Many of the key pieces of the 1984 World Series champions were in place. Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker worked in lockstep up the middle, outfielder Kirk Gibson was in his first full season, and Jack Morris and Dan Petry had their places in the rotation, with Lance Parrish receiving behind home plate, and the great manager Sparky Anderson overseeing the young club’s development. The team Sparky found when he arrived in 1979 was promising, though “as rough as a three-day beard,” he observed. It was a little tidier by 1980, but plenty of clean-up still needed to be done.

1980 became a summer of frustrations. The top of the division was set by early May, when the Yankees pulled into first place, but they never fully pulled away. Behind New York came a roiling dust cloud, kicked up by the six other teams turning end over end in their futile efforts to catch New York. Caught in that melee, the Tigers moved back and forth through every position in the standings other than first.

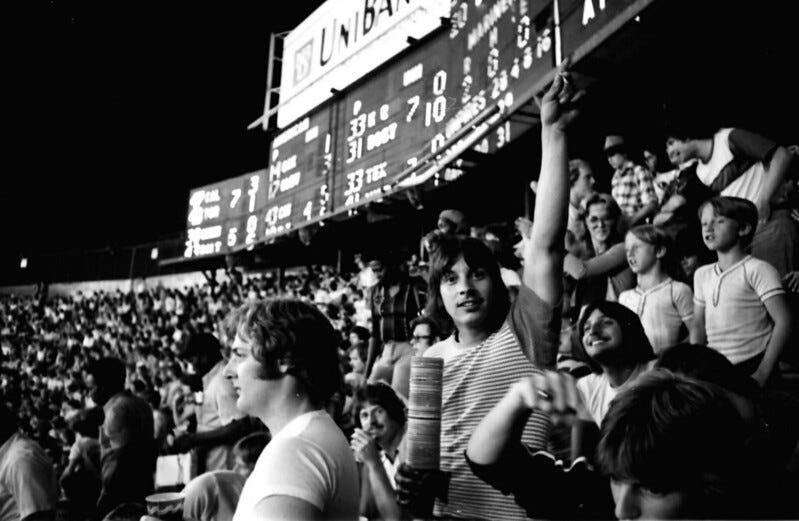

On the night of a June 16 “twi-night” double-header (it was always the double-headers), the Tigers happened to be in last place. Detroit hosted the Milwaukee Brewers and 37,040 fans came to Tiger Stadium, about a quarter of them seated in the bleachers.

For their $2, the bleacher-heavy crowd got a compelling night of baseball. The teams split the games, beginning with a 6-5, walk-off victory for the Tigers on a single by right fielder Al Cowens and ending with a 5-3 loss in which the Tigers loaded the bases with two outs in the bottom of the ninth, but failed to score.

“I think the people got their money’s worth,” the Brewers’ manager, George Bamberger said. For the price of bleacher seats, was a rather low bar, but Bamberger was certainly right. But despite a night of exciting baseball, the bleacherites were not entertained.

The next day, the Detroit Free Press sports section featured the customary recap of both games, characterizing them as exciting if straightforward affairs. Only a thorough reader might have caught the tiny blurb buried elsewhere in the paper reporting that six arrests had been made at Tiger Stadium the night before, along with a note that the only reason the police didn’t make additional arrests was because they lacked the capacity to process additional offenders on-site. In addition, the article reported that a 37-year-old man reportedly dropped his trousers in front of other spectators, exposing his buttocks in “a practice called mooning,” the writer helpfully explained.

Elsewhere in the country, readers got much more information about what had happened in Detroit the night before, via the United Press International wire report: “TIGER CROWD UNRULY.”

Once ensuing events forced the paper to cover the full story of the game, the Free Press begrudgingly gave the full story, reporting in a follow-up that the Monday crowd “threw more garbage than usual, but wasn’t as violent as it had gotten on ‘riot night,’” earlier in the season. This, too, set a very low bar.

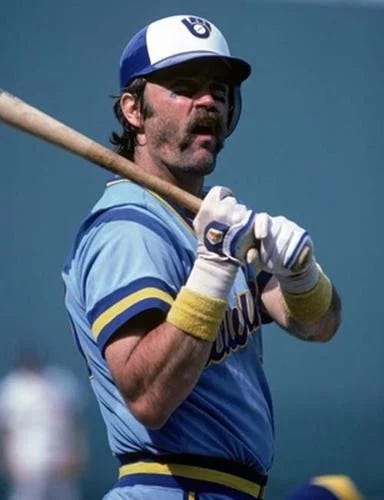

“It was a zoo,” reported “a Free Press employee,” 20 years old, who also happened to be “a regular” in the bleachers. “It got worse during the seventh inning of the second game. They were chanting obscenities at Gorman Thomas. There was a steady stream of rent-a-cops running up and pulling people out. One guy pulled down his pants1.”

Several times during both games, play was stopped so the grounds crew could clear the field of garbage. The grass underneath Milwaukee outfielders Gorman Thomas and Sixto Lezcano looked like a parade had just marched through.

Lezcano endured some paper cups filled with ice and bottles tossed into his vicinity in right field during the second game, but center fielder Gorman Thomas was abused throughout both contests, including the occasional lit firecracker.

“It’s no big deal,” the hurly-burly Thomas said. “They were throwing bottles, change, cups. One guy even threw a wine skin at me, so I know he was drunk.” Thomas showed reporters some of the change he’d picked up off the field after it had been thrown at him. As the tale grew in the telling, a new version of this anecdote emerged, quoting Thomas as saying: “When I pulled down my pants, 35 cents fell out.”

Thomas gained a measure of vengeance as he caught the final out of the hard-fought second game, turning to fire it high and hard into the bleacher crowds hanging over his head.

“They threw stuff at me all day,” he said, “so I figured if I threw at them, as drunk as they were, maybe they’d fight over it and a couple of them would get killed.” Fortunately, no fatalities were reported, so it just ended up as a nice souvenir for somebody.

One of the Tiger old-timers (by the relative standards of the young team) was utility player John Wockenfuss. Wockenfuss had seen a good deal of the bleachers since breaking in with the Tigers in 1974, and June 16 was a low point.

“This is definitely the worst I’ve ever seen,” he said. “In New York they yell at you a lot, but when people throw bombs like they did Monday night, it’s really out of control. This year they started with that stuff and it has just gotten worse and worse.”

After the game, Jim Campbell had no comment for the media, but he apologized to Bamberger and his Milwaukee counterpart, Harry Dalton. Bamberger had just returned to work after suffering a heart attack during spring training and this was the last thing he needed. The manager said Detroit was in a dead heat with New York for producing the worst fans in the league.

“It don’t make any sense to me that somebody would do something that could injure somebody else,” Bamberger said. “We’re playing the best we can. The Tigers are playing the best they can. We want the fans to enjoy themselves, have some fun. But what’s the point in throwing things?”

As a result of the Free Press’ muted coverage, Detroit residents didn’t know how bad things had gotten in the outfield. Many fans didn’t get their first clue of anything amiss until the next day, when they approached the bleacher box office windows to buy tickets. On June 17, however, those kiosks were dark and quiet, with a message taped over their shuttered windows:

BLEACHERS CLOSED FOR TONIGHT’S GAME.

Jim Campbell may not have flinched at a cartload of manure, but seeing Gorman Thomas pull 35 cents from his pants, the normally patient executive had snapped.

As we tell this story, we’d love to hear more about life in the bleachers at Tiger Stadium from those who’ve lived it. Please share this Part 1 with any Tiger fans you know…but maybe don’t ask them what they did to get rum into the ballpark back in the day.

Leave comments, send us an email, and we’ll hopefully be able to share some memories in a future piece.

Next week we’ll have the second half of this story as Campbell’s crackdown roils the city. The bleacher fans are grounded, but for how long?

On September 16: The American League gets a “Beach Ball Policy”

A practice we now know (thanks to the Detroit Free Press) is called “mooning.”

Another instant classic. Too many gems in here to count. Gorman Thomas sounds like a potential Project 3.18 hall of famer.

I was never in the bleachers but wanted to experience it in the old Yankee Stadium before it got knocked down & I must say with my lower back pain it was an awful experience. I couldn’t wait for the game to end so I could hobble outa there.

I think they were playing Boston which is always a big deal in NY. There were some interesting conversations but no rowdiness or fights.

That was my first/last time. Maybe parks should stop the beer sales even earlier like 5th inning.

Thank you Paul. 🍺⚾️