Through the Golden Gates - Part 1 of 2

In 1983, the White Sox were the surprise powerhouse of baseball, and we’re making that our happy thought this week.

The Chicago White Sox’ record-setting 2024 season is a debacle that launched a thousand contextualizing statistics, and though we mostly do history here, permit us just one of these:

Before 2024, the White Sox had played in 19,044 games since beginning major-league play (as the Chicago White Stockings) in 1901. Despite posting losing records in seven of the previous ten seasons (and only one non-COVID season with a winning record), the team’s cushion was such that it entered 2024 with an overall winning percentage of .502.

A modest winning season could have kept them in the black, but alas, that is not what we got. Chicago’s 41-121 performance dropped their franchise win-percentage all the way down to .4995. Now all that stands between the White Sox and a losing record is one ten-thousandth of a point and the standard rounding up.

Yes, it has been a tough year on the South Side.

In recognition of that, we thought this week might be a good time to open an escape hatch from the dreary present and revisit a time when the White Sox were the bullies of the American League and the undisputed kings of Chicago. The grim irony is that some of the people celebrated for the successes of 1983 are the same ones being blamed for the Sox’ present-day defenestration. Sometimes all that separates heroes from villains is an expiration date.

Anyway, enough gloom. This is to be a story of uncomplicated happiness and a reminder that midnight and sunrise are practically neighbors. The Chicago White Sox will be back...unless they move to Nashville…ahhh, we’re doing it again!

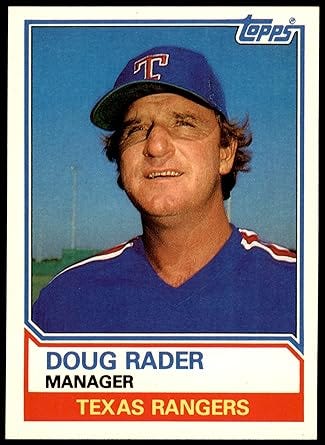

In mid-August, 1983, Doug Rader, the manager of the Texas Rangers, got an advance scouting report on an upcoming opponent: the Chicago White Sox.

“They’ve just been winning ugly,” Rader told the media. “From the reports I get, I don’t think they are playing that good. People we’ve come across who have just finished playing them say they don’t look too great.“

And what, exactly, was an “ugly” win? Rader never really said, but his dismissive characterization was parsed in a few different ways.

For example, on a recent road trip, the White Sox had gone 8-3 despite hitting just .209 as a team. There were three close, extra-inning games during that trip, and the Sox won them all. In their three losses, they’d been blown out. Was that ugly?

According to another interpretation, the Sox were a team without classic power hitters in the lineup or a reliable stopper in the bullpen. Not pretty. The Washington Post would later sum them up as “an unlikely team of strong-armed cast-offs, also-rans, and clubhouse cutups, managed by a part-time lawyer.”

When Doug Rader opened his big mouth, that motley group was five games ahead of the Rangers with about two and half months to play. The Rangers weren’t even the Sox’ closest competition, which Rader acknowledged. “I said all along, the only way we can compete at the end is if the other ballclubs back up to us,” Rader said. “It looks like Kansas City and California are trying to cooperate. I wish Chicago would start listening.”

In fact, Chicago was all ears.

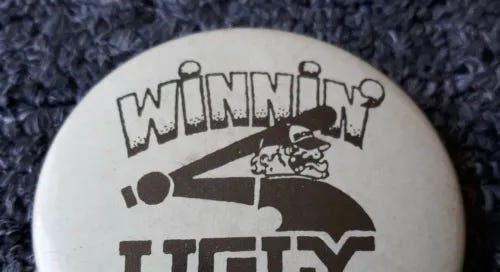

In that August series in Texas, the White Sox took three out of four. When Rader and the Rangers traveled to Comiskey Park at the end of the month, he discovered that his his offhand deprecations had been remixed and re-released in Chicago. Outside the Baseball Palace of the World, vendors sold t-shirts to eager customers that proudly proclaimed the White Sox as “Winnin’ Ugly.” Or: “Another Ugly Win.” Though they were unsanctioned and not sold inside the park, these popular shirts had found their way onto some of the White Sox players, surreptitiously worn under their red and blue double-knit pullover jerseys.

Doug Rader knew what he was in for going into that two-game series, and he took it with relatively good humor. “Ugly, ugly, ugly!” chants rang through the park and a large banner rolled out in the upper deck: “White Sox, We’re Ugly, Too.”

“They were all over me,” Rader said. He protested (too much) that he “never meant it in a derogatory way.”

I was just describing the way they win. It’s amazing how you say something and, jeez, I didn’t give it a second thought. I just thought I was describing it accurately. I was, too. There’s nothing classic about the way they’re winning. They are winning ugly. But any way you win is tremendous. I wish we could win a few more ugly ones.

Classic?

I have great respect for their club, but when you get three hits and score three runs, that’s not considered a classic kind of game.

The t-shirt designers began working on new designs, but Rader finally decided to bail out. “Aw, I didn’t mean nothin.’ I’m no oil painting myself.”

The Sox swept the August 29-30 series, their final games against the Rangers that season. During the ninth inning of the second game, Chicago led, 5-0, and another banner unfurled on a sight line with the Rangers dugout:

“Who’s Ugly NOW?”

If you don’t know much about the 1983 Chicago White Sox, look, it’s understandable. Fans of the White Sox are not wrong to feel that their team is consistently overlooked and underappreciated, and this particular team was neglected even in its own time. And, being born that same year, we can say with authority and no small regret that that 1983 was “a long time ago,” and all of this history is well on its way to slipping under baseball’s relentless tectonic plates.

There are a couple of familiar faces, for better and worse. On the positive side, two future Hall-of-Famers, Carlton Fisk and Harold Baines, anchored the offense. The team was owned—as it is today—by Reinsdorf, then 47 years old. In this era, Reinsdorf often worked in tandem with another ownership partner, Eddie Einhorn, a former sports television executive who stepped back from day-to-day operations a few seasons later. And the manager is familiar: 38-year-old Tony La Russa, in his sixth season managing the White Sox (he is the part-time lawyer the Post referenced, having finished his J.D. in 1978 while a minor-league manager).

After that, though, unless you are a very passionate White Sox fan, the rest of this group may not ring many bells. We’ll add a note of flavor here and there but we’re not going to over-exert ourselves in the process:

The Lineup:

Carlton Fisk, Catcher – just three years younger than La Russa Tom Paciorek, First Base Julio Cruz, Second Base Jerry Dybzinski, Shortstop Vance Law, Third Base – member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints--that will be relevant later Ron Kittle, Left Field – 35 home runs, 100 RBIs; he was the AL Rookie of the Year! Rudy Law, Center Field – 50% of all historic major-league players surnamed “Law” were on this team Harold Baines, Right Field Greg Luzinski, Designated Hitter

The Starting Rotation:

LaMarr Hoyt – 24-10, 11 complete games; he won the AL Cy Young Award! Richard Dotson Floyd Bannister – a 1982 All-Star with Seattle and Chicago’s big offseason free agent, signed a 5-year, $4.8-million-dollar contract Britt Burns Jerry Koosman – Miracle Met, now 40 years old, made 24 starts; should really be in the Hall of Fame

Think of the 1983 White Sox like a baseball version of Robinson Crusoe, and the title character will be played by Roland Hemond, the team’s general manager.

Hemond was an uncomplaining baseball lifer, one of the nicest and most well-regarded executives in the industry, so much so that his book of phone numbers had 2,500 entries. By 1983 he had spent 31 of his 53 years working in baseball and the last decade as the general manager of the White Sox. Hemond was on his third ownership group, hired, consistently retained on the basis of his particular set of skills.

He built team after team on shoestrings, approaching each season with ingenuity and enthusiasm, no matter how bleak the outlook and bare the cupboards. The success of his teams in the early 1970s helped quiet talk of a Seattle relocation, and in 1977 he partnered with new boss and impoverished mastermind promoter Bill Veeck to pioneer the “rent-a-player” strategy at the dawn of free agency, producing the “South Side Hit Men” club that won 90 games only to fall apart when its stars signed long-term contracts elsewhere.

He’d hang on a few more years, but that 1977 team was Veeck’s last real stand in baseball–his grocery-store margins weren’t going to cut it in the dawning big money era, and in 1981 he sold the team to Reinsdorf and Einhorn, who made a huge splash by signing free agent Carlton Fisk for $3.3 million dollars in their first offseason.

Much of the rest of the 1983 team bore the usual Hemond hallmarks: upside-plays, multi-player trades, and careful attention to the bottom line. Hemond’s White Sox had never set the league afire, but they rarely underperformed compared to the money they cost, and pleasant surprises were not uncommon.

In 1981 and 1982, the White Sox had finished in third place in the American League West, and Chicago was eager to see the team take that next step forward into real contention, but they got off to a truly ugly start that spring. The two biggest bats, Fisk and Luzinski, were hitting below .200. The team’s big free agent, Floyd Bannister, “was not living up to his $950,000-a-year salary.” La Russa tinkered with the sputtering lineup and was knocked for leaving starting pitchers in too long in an era where the balance was tipping toward five and six-inning starts and bullpen finishes. In his sixth year with the White Sox, La Russa became a prime target of fan frustration, so much so that he later said he stopped bringing his family to Comiskey Park because the boos gave one of his children a headache. “It’s sad what Tony’s had to go through,” Hemond said later. “He’s one of the great young managers to come into the game.”

At one point in May the Sox had been 16-24 and in sixth place, tied for last in team batting and in the bottom two for fielding and pitching. The great young manager’s days looked numbered.

La Russa moved Carlton Fisk up in the batting order, sparking a public fight with the team’s star player, but the young manager put Fisk in the No. 2 spot and threw away the key. From there, Fisk raised his batting average by nearly a hundred points. The pitchers got accustomed to La Russa’s reluctance to go into his bullpen and started finding ways to survive a third trip through opposing lineups. Floyd Bannister won nine straight games after the All-Star break. He, Hoyt, and Dotson went 29-5 in the second half. Greg Luzinski hit three balls over the roof of Comiskey Park—no one else had ever hit two such balls in a career. The White Sox moved into first place on July 18 and began pummeling the rest of their woeful division.

They went 22-9 in August, capped off by Doug Rader’s public humiliation. They were nearly ten games up on their nearest competition, the Kansas City Royals, and the only team in the division with a winning record. Around that time, the “Winnin’ Ugly” merchandise for sale around Comiskey Park got an upgrade, added to the bottom:

Jerry Reinsdorf still refused to let anything like that be sold inside the ballpark. No lead was safe in August. He needn’t have worried. The team went 22-6 in September.

Though they are almost forgotten today, the 1983 White Sox were an island in mid-century Chicago sports’ dark waters. The Bears, Blackhawks, and Bulls could not escape their respective divisional playoffs, and things in baseball were much worse. The Cubs had not won anything since their 1945 pennant and the Sox’ previous pennant, from 1959, was nearly old enough to run for Congress. There were plenty of adults in the city who’d gone their entire lives without experiencing any playoff baseball. Meanwhile, fans in New York and Los Angeles had each enjoyed three World Series appearances in the last six years, the Yankees and Dodgers waving down at Chicago as they flew back-and-forth high overhead.

If the city did show up in the news, the headlines were usually embarrassing. The city’s credit rating had recently been downgraded by the Standard and Poor’s agency, from A- to BBB+, reflecting Chicago’s “adequate capacity” to pay interest and principal on its debts, down from a “strong capacity.” This change impacted the city government’s access to credit lines and generally was not a good look.

Nor were the ongoing “Council Wars” that saw 29 opposition aldermen build a brick wall in front of the agenda of the city’s newly-elected mayor, Harold Washington. The City Council was riven along racial lines, with 28 of Washington’s council opponents being White and those that supported him largely Black, as of course was Washington himself. All the combatants on either side were Democrats, so ideology clearly wasn’t the sticking point.

In a deeply segregated city, Comiskey Park was becoming a bright spot. The White Sox’ success that season helped build their growing Black audience, augmenting baseball’s predominantly-White fanbase. Even die-hard Cubs fans were starting to show up in greater numbers, tired of standing vigil at their team’s annual summer collapse at Wrigley Field.

“I don’t want to be a fair-weather fan,” said Phil Donohue, an influential local talk show host, “but there is a limit, isn’t there? Being below .500 in the won-lost column is one thing, but firing Ernie Banks and hanging beer signs on the scoreboard are all too much to bear.” There was even talk of installing lights at Wrigley Field; if anything was the limit, surely that was it.

Not everyone welcomed the new arrivals. Studs Terkel, the renowned Chicago oral historian and devoted White Sox fan, was quoted as saying that people who quit cheering for losers to applaud winners ought to be lined up and shot, but fortunately most people were more willing to make room on the bandwagon.

With fans north, south, and west—perhaps the first time either baseball team could credibly claim all three quadrants—the 1983 White Sox drew more than 2 million fans, beating the 1969 Cubs’ previous record by nearly half a million.

By the middle of September the Sox’ division lead was up to 16, their magic number was already in the single digits, and the “Division Champs” merchandise, previously banned, was quietly welcomed inside Comiskey Park. It was time to celebrate. “I have a feeling that all this is going to turn this city around,” LaMarr Hoyt said. Maybe that was asking too much, but there was no question that in Chicago in 1983, winning had never looked so good.

Next week, the White Sox officially clinch their division and throw some outstanding parties at “the oldest and loveliest” of ballparks.

Here’s Part 2: “Profiles in Courage”

In the meantime, please do share this with any White Sox fans who may need to disassociate from the present for a while.

Paul, I was ready to call you out for misattributing the Chicago White Stockings to the White Sox, but, alas, you are correct: they began as the precursor to the Cubs from 1870-1889, and the nascent AL team in Chicago adopted the name from 1900-1903. Kudos!

Nice work. My take as a casual fan whose focus drifted over the last 4 decades of life in LoCali…In retrospect that lineup stacks-up pretty well. Luzinski was a beast. Paciorek had had a good stint with the Dodgers but their infield was loaded and he deserved more playing time. Fisk is in the HOF isn’t he? That he boosted his BA that much is cool, but obviously he just had a cold start. Etc.