Through the Golden Gates - Part 2 of 2

Nothing could stop the 1983 “Winning Ugly” White Sox…except the playoffs.

Last week, we set the table for today’s story about a very happy, very Chicago moment, so be sure to check that out first.

After the hapless Doug Rader dismissed the White Sox’ 1983 successes as “winning ugly,” Chicago went on a 57-19 sprint to finish the season. Meanwhile, the rest of the American League West, including Rader’s Rangers, crumbled.

In 1982, people thought baseball might have reached peak competitive balance; none of the four division races were decided entering the final week of the season, and two races required all 162 games to determine the victor. Now it was back to the drawing board.

Only 12 title races in major league history had been decided by more than 16 games, most recently the 1975 NL West, flattened by Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine. It seemed the 1983 White Sox would become lucky 13. “No one will accuse us of sneaking in, the way we’ve been playing,” manager Tony La Russa said. Ugly or pretty, the Sox were kicking down the front door.

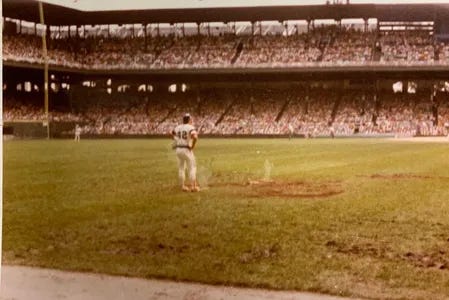

Going into play on September 16, Chicago’s magic number had fallen to 2. If the White Sox won that night and the Kansas City Royals lost their game against Oakland, the race would be over, a full two weeks before the end of the season. 38,502 people came to Comiskey Park to see a title clinch, and maybe participate a little, too.

Poor judgment had been a feature of “recent” White Sox postseason teams. There was the 1919 team, whose players demonstrated some of the worst judgment in the history of the sport when they conspired to throw the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds. And, during the previous go-round, there was the astounding case of the city’s fire commissioner, an enthusiastic White Sox fan by the name of Robert Quinn.

After the 1959 team clinched their pennant, Quinn—wanting to inspire an atmosphere of celebration—ordered the city’s air raid warning system to be sounded, terrifying tens of thousands of Chicagoans into thinking the Soviets had launched a Cold-War nuclear attack. Rather than celebrate the “Go-Go” Sox, people fled to their basements and said what turned out to be premature goodbyes.

Assailed by thousands of angry Chicagoans, the mayor, Mayor Richard J. Daley, also a White Sox partisan, made a public apology the next day. Had Daley been a Cubs fan, Quinn surely would have been fired, but the mayor was from Bridgeport.1

The organization was determined to do better on September 16, 1983, as the Sox prepared to win the American League West for the first time. The first attempt coincided with the start of a series against the Seattle Mariners who were, on paper, also a major-league baseball team.

Throughout the game, pleas for calm flashed up on the scoreboard.

“Sox fans, please respect the people and property surrounding the ballpark.”

Rather than lead with sticks of expulsion and prosecution, the team had decided to try offering carrots (though, we must say, with rather clunky sentence structure):

“Our players will come out on the field if you will stay off the field.”

That night, Floyd Bannister pitched a complete game two-hitter for Chicago, earning a ninth-straight win. He struck out a career-high 12 batters and was second in the league in strikeouts overall. Like his team, Bannister seemed to have forgotten that baseball was supposed to be a game of failure.

The game remained close until the eighth inning, when the White Sox scored six runs and got the party started. The visiting Seattle pitchers quickly abandoned their bullpen for the safety of the dugout, where security personnel began to cluster.

When the Mariners batted in the ninth, a banner unfurled in the second deck: “You Can’t Beat Ugly.” After Bannister’s final pitch, hundreds of fans made for the field, and the White Sox threw their plan into motion.

A group of ushers quickly encircled the pitching mound, protecting it with their bodies, while another group began stringing up a rope around the infield and clearing people on the wrong side of the line. Fans in the outfield were left unbothered, and the team even invited them to stay on the grass and watch the rest of the Oakland/Kansas City game on the Diamond Vision scoreboard. Soon there were three or four thousand people standing calmly outside the cordon, “as if in a Peter Bruegel painting.”

The excitement on the field waned as the Royals held on in a tight game against the A’s and eventually took a 6-5 lead in the eighth. The White Sox’ magic number stalled at one; in the clubhouse, the Korbel Extra Dry champagne remained on ice and the sheets of quick-drop plastic installed above the lockers stayed rolled up for another day.

The players were unconcerned by the delay. They were polishing off their season in mid-September and life was just a series of silver linings. “Now we can go out Saturday and win it for ourselves.” Bannister said.

The second game of the series was delayed nearly 40 minutes by heavy storms that had rolled through the Great Lakes region in the afternoon. It was tornado weather (making it even more important that the city use their warning sirens responsibly), but luckily no funnels were sighted and the bad weather moved through.

Despite the storms, a standing-room crowd of 45,646 had come to see a clinch that no longer required any help from the Royals. “People were scalping tickets in the pouring rain,” one fan said. “I’d never seen anything like it.” The Sox had won their last 15 straight home games, and thousands of people spent the game outside Comiskey, awaiting what felt inevitable. Mounted police and K-9 police units bounded the crowd on 35th Street, and the streetside fans generally minded their manners. One commentator suspected that the totality and certainty of the White Sox victory actually tamped down on the craziness—the team was too good to surprise.

The division race might have been a joke, but the decisive game was a good one. The Sox’ Vance Law treated the fans to a suicide squeeze bunt in the fourth inning, scoring Tom Paciorek and breaking a 1-1 tie. “Ugly” chants volleyed around the ballpark.

With the success of the rest of Chicago’s rotation, uber-veteran Jerry Koosman was unlikely to receive a start in the playoffs, so this was his big moment, and he threw eight strong innings. The Sox held a 2-1 lead going into the bottom of the eighth.

If you happened to be a commuter around 10:30pm on the north/south Dan Ryan expressway on that night, you have probably never forgotten the sight.

Earlier that evening, around 6:00pm, the Milton Johns Company mattress factory, located at 3920 South Federal Street, caught fire. The shuttered factory had long been a tempting target—area residents said there had been nearly a dozen fires in that building since the former owners abandoned it. Before the fire began, witnesses saw two “youths” running from the building carrying a gasoline can. Their thirteenth fire was the one that finished the job.

The five-alarm blaze burned for hours, cooking off cars parked in front of the building and burning down electrical poles, cutting power to parts of the nearby Robert Taylor Homes public housing development. The fire department spent as much water on the nearby apartments as they did the factory, making sure the night’s 22 mile-an-hour winds couldn’t carry the flames across the street.

An enormous plume of black smoke rose from the site, visible for miles, and people stuck in traffic on the Dan Ryan reported they could feel the heat inside their vehicles. Those same drivers could see the heavy clouds scudding east across Lake Michigan, filled with flickering lightning and the rumble of distant thunder.

Just across the highway from the factory fire was white-lit Comiskey Park, and at around 10:00pm the park’s famous exploding scoreboard shot fireworks into skies of smoke and thunder, the flash quickly followed by the roar of a full house: Harold Baines had just hit an eighth inning home run to extend the Sox’ lead.

It wasn’t quite over at that moment. The Mariners managed to tie the game off of Koosman and Dennis Lamp—the team’s best stab at a closer—in the ninth inning. The White Sox got right back to work, loading the bases in the bottom of the ninth and bringing Baines up again. The right fielder hit a sacrifice fly into center field to push Julio Cruz across home plate and end the game. 16 straight wins, one division championship.

The White Sox called the same play they had the previous evening. The fans could have the outfield, and that worked out fine, though there was more interest in souvenirs this time. Some left Comiskey Park an hour later with a swatch of turf held proudly over their heads. One fan said his prize came from left field. “I’m going to cherish this. I’m going to plant it and grow it in my house and keep it all my life. Just think about it. We are the champions. Not New York. Not Los Angeles. Chicago.”

Beneath the park, the White Sox got to celebrating. General manager Roland Hemond left his address book safe in his office. “Just in case something happens. You just don’t replace a phone book with 2,500 numbers in it. Always got to think ahead in a business like this.” But he was quickly back to making calls—trying to reach Bill Veeck at home. Hemond knew Veeck’s number by heart, and he wanted to make sure the efforts of the White Sox’ last owner were recognized.

“That’s [Veeck’s] man,” Hemond said of Harold Baines. “Everybody thought Bill just signed Harold because he was his neighbor, but that man can play!” Nobody picked up, so Hemond left a message. “Bill, wherever you are, Harold Baines can play!” Veeck eventually called back, and he had to agree.

For his part, manager Tony La Russa wanted to give the night to Hemond for having finally carved a path out of the White Sox’ thicketed circumstances.

“Everything in this clubhouse has Roland Hemond’s name on it,” La Russa said. “Every good thing that happens. We look for the chink in his armor and we never find it. Finest man I know.”

That wasn’t just the champagne talking. Even under the influence, La Russa called them as he saw them. Asked to reflect on the players’ success, some managers might have fallen into hyperbole, but not La Russa: “They might not be the 25 best humans in the world, but they are professionals.”

He wasn’t saying anything the players wouldn’t agree with. They knew who they were; they just hadn’t let that stop them.

“Look around this clubhouse,” reliever Dennis Lamp said. “We’ve got a bunch of guys nobody else wanted.”

“There aren’t any stars here,” Jerry Koosman agreed. “Stars are something in the sky. We have guys who don’t get much attention who contributed to this all year long.” Well, Harold Baines, was looking like he might be a star, and Pudge Fisk had a locker nearby, but Koosman’s broader point was valid.

Mayor Washington called into the clubhouse and yelled “Viva Baines!” drawing a smile from the night’s quiet hero. The mayor was out of town on business, but he promised the city would be ready to (responsibly) celebrate the AL West champions. “We won’t set off the sirens,” Washington said. “Only Daley could get away with that.”

Reinsdorf and Einhorn were in the thick of it. “We’ve made the people in this city feel like winners again for the first time in a long time,” Einhorn said. “We’ve proven that something can get done in this city. Chicago doesn’t have to think of itself as a loser anymore.”

It had been such a long road for Chicago, the White Sox, and Roland Hemond. Together they had withstood the buffeting winds of relocation in the early 1970s and the financial white-out of the first free-agency years, circling back from one dead-end after another to try a new path. “You gotta spend some time in purgatory before they open up the golden gates,” Hemond said during the celebration. He gestured at the festivities sloshing all around him. “Well, they’re open.”

Despite overserving themselves into the wee hours, the White Sox still had to report to work the next day for the finale of the series against the hapless Mariners. Of the night before, Tony La Russa said, “We played like champions and we celebrated like champions.” The manager was right there in the trenches with his players. “I’m still trying to figure out how a man can feel so good and so bad at the same time. We didn’t get out of here until 4:30 am. There were four different parties here in the stadium.” Only pitcher Richard Dotson had left early; he was scheduled to start the next day.

The players dragged themselves in, ashen-faced but smiling. Ron Kittle had bandages on his hands; he had cut them while groping around in the emptied champagne cart and finding only a handful of broken glass. Kittle initially couldn’t find his cleats, but after a careful search he discovered one in the hallway and another on the foot of a bleary-eyed teammate.

Elsewhere, LaMarr Hoyt belatedly rediscovered a burrito he’d apparently set aside for safekeeping during the party. Meanwhile, Greg Luzinski was nowhere to be found.

Third-base coach Jim Leyland might have been the worst-off.

“When I finally left the ballpark last night, I got into my car and thought somebody had stolen my steering wheel and dashboard. I called the cops right away. Then I called them back. Realized I had gotten in the back seat.”

What happened after that was unsaid, but we’re going to tell ourselves he called a cab.

Even poor Vance Law had been tarnished. “I’m a Mormon,” he said. “I’ve never tasted alcohol. But after what went on here last night, I can’t say I’ve never had it poured on my head or squirted in my eyes. Stuff burns.”

Battling a colorful assortment of hangovers and poor choices, the White Sox won as ugly as they had ever looked or felt, blowing the Mariners away in a 6-0 victory. Dotson pitched a shutout and Harold Baines hit another home run. The last-place Mariners slunk away in shame.

“Some of these guys, the last time I saw them, their faces looked like they’d been blocking punts,” La Russa said. “But we’re 17 games up now? I guess they can play as hard as they party. And Jim Leyland, he showed me a lot today, too. Profile in courage.”

Chances are, if the 1983 Chicago White Sox had gone on to win the World Series, you would have heard more about them in the subsequent four decades. But baseball so rarely works that way, which makes the moments when it does so enduring. Jerry Koosman could tell you something about that.

Postseason baseball is the greatest dice-roll in American team sports. The pre-playoff era was so satisfying (for the victors) because only the best two teams from the regular-season got a chance to compete for the ultimate prize, but in all subsequent formats, a few good teams inevitably get bounced early.

The 1983 American League Championship Series, the White Sox faced off against their only peer in either league, the Baltimore Orioles, whose 22-year-old MVP shortstop, Cal Ripken Jr., had led his team to 98 wins and earned the only major award not claimed by the White Sox. The Orioles received home-field advantage and the White Sox won the first game behind LaMarr Hoyt, but that was it2. In the next three games, Chicago scored just once. The Orioles took the pennant and eventually the World Series.

The 1983 White Sox were called the “Miracle on 35th Street,” but no divine intervention was utilized or even sought. After the team clinched the division, the play-by-play announcer, former player Ken Harrelson, offered his assessment of the White Sox, and we think it holds up, despite the eventual outcome:

When this season is over—regardless of what happens in the playoffs and World Series—only one of the major league clubs will be able to say they played to their full capabilities. That club is the White Sox. And I’ll say this even if they lose in the playoffs.

The players performed and some even overperformed. Hemond won his trades, La Russa pulled the right strings, and the owners spent and spent wisely. Everyone had simply done their best, and that had actually been enough.

Even sans trophy, these Sox were loved because of what they showed Chicago’s weary fans: a demonstration of what 25 thoughtfully-deployed professionals could do, and proof that no matter who or how, all wins counted the same.

Any White Sox fans out there with stories from 1983? We’re all ears.

We recently heard a big fan of Project 3.18, who put in a special request…they wanted a Halloween story. We were intrigued, but uncertain. Was there a nonfiction baseball history story out there that could pull off Halloween? The supernatural? Goosebumps, thrills, and chills? Could we do a story like that?

…

…

On October 21: “A Haunted Player”

Rest assured that this 1959 air raid debacle will one day get the full Project 3.18 treatment.

The White Sox made the playoffs again in 1993. Though they won two games on the road, they lost all three of their home games in that series against the Toronto Blue Jays. Between 1959 and 2005, White Sox fans didn’t get to enjoy a single postseason win at home. Oof.

This fantastic two-parter jogged my memory about an article I read in the 1984 Bill James Baseball Abstract. For whatever it is worth, Mr. James didn’t use the words “winning ugly,” but he did explain why he believed one particularly effective regular season strategy the White Sox used did not translate to playoff success. He notes that the Sox were 38-13 against the four worst teams in the AL while their LCS opponents the Orioles were only 29-20 against those same teams.

His advice to the White Sox skipper: “You said going into the playoffs that you thought baserunning might be the difference in the series, and it was, Tony. It sure as hell was. Aggressive baserunning does not work against a good team; the same baserunning move that is a ‘positive’ percentage move against a bad team is often a ‘negative’ percentage move against a good team. You [try to take an extra base] all year, and all year it helps you win ball games — you beat the crap out of the Seattle Mariners and the Minnesota Twins — and then you do it against the Baltimore Orioles and it helps them win ball games.”

Nice to get an early glimpse of Jim Leyland - universally beloved throughout baseball world. During my 36-1/2 years in Chicago, this was the closest they ever came to being on top - close, but no cigar. Of course, the lovable loser Cubs didn’t get it done either.