Too Many Angles

In 1977, technology threatened to make umpires obsolete, and it’s been doing it ever since.

Whatever else they have been or will be, umpires are a part of baseball’s tradition, as fundamental to the experience as a soft cap with a round crown and a stiff bill. Umpires became a part of this tradition at a time when they were necessary—for the first century of baseball, there was no better way to police the edges of the game.

Since then, however, emerging technologies have made the diamond a contested space where progress and tradition grapple. The results of this ongoing conflict have sometimes been rather silly. Regular readers might know that our least favorite of these half-measures is the standardized use of “K-Zone” technology in baseball broadcasts. In its illegible wisdom, MLB has used K-Zone to let viewers know—with precision and in real-time—just what ball and strike calls the umpire has missed, while letting each and every one of those calls stand. It’s as if everyone involved in King Solomon’s parable decided they were fine with half a baby, actually.

After a successful test-run in spring training 2025, using K-Zone as more than an “FYI” to viewers seems within reach, but recent reports suggest a full implementation of an automated balls and strikes challenge system (ABS) might be held hostage in the upcoming collective bargaining process, which is generally shaping up to be a doozy. Should one or both sides succeed in keeping ABS out of the regular season for yet another year, all we’ll have of it in 2026 are more players using a mocking “head-pat” gesture after what they think is an egregiously blown call, asking the umpire for a contractually-prohibited review.1

The latest wrangling over the use of ABS and its impact on the “human element” of umpiring is just the latest round of an eternal battle. Given umpires’ remarkable skills (despite their occasional misses) and their essential part of baseball’s legacy, we’ll probably never do away with them entirely, even once the pros of robot umps clearly outweigh the cons. We’ll just fuss every few years over some incremental change in a way that, looking back nearly 50 years later, will seem charmingly ridiculous.

Big things were happening in Atlanta Fulton County Stadium in 1977. The Braves’ motivated media mogul owner, Ted Turner, made his second score in free agency, signing outfielder Gary Matthews to a five-year, $1.8 million contract (and earning himself a one-year suspension for tampering in the process). But Sarge was a Brave, Turner’s suspension was on hold pending his retaliatory lawsuit against the commissioner, and the team was ready to open their ballpark for the new season.

Matthews was not the only shiny toy Ted Turner purchased in the preceding offseason. He had also procured—for nearly the same amount of money—the first video-capable scoreboard in the National League. The Braves’ were looking for a better title but until one was found, the new board was known by its brand-name: the Video Matrix. Installed along the second deck in center field, it was 20 feet high and 40 feet long and cost $1.6 million dollars.

Buttressed by prominent ads for cigarettes and soda pop, the Video Matrix (one sarcastic commentator suggested calling it “Turnerscope”) could use its middle third to display TV-quality video, delivered by a new arm of the Braves’ broadcast team.

The Video Matrix’s mission commander was Dave Lane, who was also the sports director for Turner’s WTCG-TV, Channel 17, which had begun transmitting nationally by satellite just months before, in December 1976. It remains on many televisions today as the TBS network. Lane and three assistants were charged with “programming” the new video board the same way they might program three hours of air-time. Friday, April 15, the home opener, was their first broadcast, and the last-minute preparations were predictably hectic.

“The thing is,” Lane explained, “we only got this thing working about 7 PM Friday and we were supposed to start using it at 7:15.”

One of the very first replays shown on the 20’ by 20’ screen was entirely unobjectionable: the footage of Hank Aaron’s 715th home run, struck in 1974. The Braves were retiring his number 44 that night, and the similarly retired Aaron watched from the field as his biggest moment was blown up to a fitting scale.

As a media-savvy team who had just invested an enormous sum in a giant television, the Braves had grander ambitions than canned footage or static portraits of the players as they came to bat. The Video Matrix was also rigged for instant replay. Lane and his team could play back footage from the WTCG broadcast feed just seconds after it was recorded. Only one other team in 1977 had the power to do this—the Yankees, and the way the leagues were divided in this era meant Atlanta was the first place anyone on the Senior Circuit would regularly interact with this new technology.

Before the first game, Lane huddled with Turner and his vice president of player personnel, Bill Lucas (effectively MLB’s first Black general manager), to decide how to introduce instant replay to the NL. According to the Macon Telegraph, this may have been their first meeting about it:

They talked about throwing instant replays up there for one and all to see. The question was whether or not to ask the umpires about doing it. Lucas suggested that it might be better just to do it, the thinking being that the group might disapprove.

“We’ve got to do it this first night,” Turner said, and asking for forgiveness rather than permission sounded right to him. Someone drily observed that, at worst, Turner would be suspended by the commissioner, and what else was new?

This was truly uncharted territory for everyone involved. “It’s the only one,” Lane said, “so there are no guidelines for its use.”

One of the huddlers wondered how many innings it would take for instant replay to instigate a controversy. The answer turned out to be lucky 13.

The first National League umpire crew to have their work checked in real-time was that of Ed Sudol, Bruce Froemming, Terry Tata, and Dick Stello. From how the series played out, it is clear that some of these men, particularly Froemming and Sudol, had deep, deep misgivings about in-park instant replay, but nothing Dave Lane chose to put up on the Video Matrix during the first game brought a protest from the umpires. Maybe they just had a really good night. The Braves won that game, 4-3, and everybody but their opponent, the Houston Astros, called that a good start.

On Saturday night, the Braves showcased their early triumphs in free agency, starting Andy Messersmith, whose arbitration and pioneering free agency in 1975 helped make Gary Matthews a millionaire a year later. The latter showed his gratitude by hitting a 2-run single in the seventh inning that helped Messersmith win his first game of the young season, 4-3.

In the fourth inning of that game, Dave Lane got into trouble.

High up in the production booth, Lane decided fans might like to another look at some of home plate umpire Bruce Froemming’s borderline ball and strike calls. The players were also interested.

“They were all watching it,” Froemming said, appalled. “One time [Braves’ catcher Vic] Correll looked up there and said, ‘Yep, that was a little outside.’ Then, when Messersmith took a look, that was it. We had to get it straightened out.”

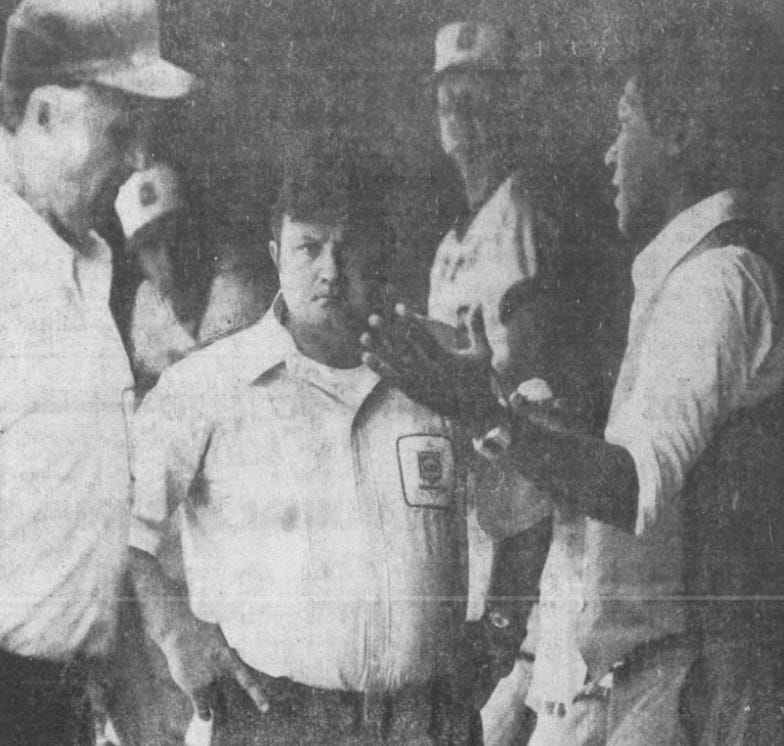

In the third inning the umpires had a quiet on-field word with Braves manager Dave Bristol, requesting that the replay crew stop showing ball/strike replays. This message apparently did not have the desired effect, so after the Houston fourth inning the whole crew left the field together, sheltering in the Braves’ dugout and asking to see Bristol’s supervisor. Bill Lucas responded to the scene and Froemming gave him an earful.

“That TV is there for spectacular plays, for the fans,” the umpire said. “It’s not there to lynch us.”

Froemming said the Atlanta players had been sympathetic. “When we were in the dugout they [agreed] it was ‘bush,’ a bush thing to do. And it was. That guy upstairs is to blame, the guy who chooses what goes up there. They should check his stats, put a camera on him all day, and see how he feels. The busher in the box, that was the trouble.”

The umpires believed that showing their mistakes to a live crowd risked their lives. And not entirely unreasonably. The 1970s was baseball’s unruliest decade since perhaps the first World War. Crowds regularly took their disaffection out on the entertainers, often using projectiles, and there had been many close calls. Plus, the first time instant replay had been used, in 1976, Yankees’ owner George Steinbrenner had practically weaponized it, ordering his staff to replay missed calls until the commissioner, Bowie Kuhn, intervened.

“You remember,” crew chief Ed Sudol said, “what happened in Yankee Stadium last year. They almost had a riot because of those replays2.”

“You can’t just stand out there,” with the crowd watching the mistakes, Froemming said. “All hell could break loose.”

Lucas and Turner were diplomatic, promising to stop replaying balls and strikes. Unofficially or officially, this has become standard practice, and with good reason. As one observer put it in 1977:

If they’re going to show calls on balls and strikes on that screen, they might as well install an electronic umpire behind home plate. John Wayne and Wyatt Earp wouldn’t umpire under those conditions.

Turner insisted the team was sensitive to the umpires’ concerns, and some controls were in place. “We don’t want to cause any trouble,” Turner said. “We have a slide ready to slip in there when there’s a controversial replay. We’re not going to try and make the umpires look foolish. If we do something accidentally, we’ll just ask the fans to cool it.”

The next afternoon, Sunday, the umpires were on edge. There were no ball/strike calls up on the Video Matrix, but they knew Dave Lane, the “Busher in the Box,” was up there somewhere, watching and judging.

“I thought that was funny,” Lane said of his new honorific. “I don’t take it personally, but I can’t see anybody looking at me or yelling at me.”

The individual operator was the sole arbiter of taste in early replay, and while Lane said he was intentional in reviewing plays to avoid replaying something that might rankle, he was nonetheless winging it.

In the fourth inning of Sunday’s game there was an exciting play. The Astros had already scored a run and were up, 2-0, with runners at second and third. The Braves were pitching their knuckleballing immortal, Phil Niekro, who was both 38 years old and only about midway through his 24-year career.

Niekro knew better than anyone that the knuckler giveth as well as taketh, and in that fourth inning with one out a knuckler escaped Braves catcher Biff Pocoroba3 and made a dash for the back wall, prompting Houston’s lead runner, Bob Watson, to dash for home. Niekro hustled in the same direction, preparing to receive the ball from Pocoroba and make a tag. The catcher gathered up the ball and threw it to Niekro just as Watson arrived, resulting in a close and exciting play. Home plate umpire Terry Tata was right on top of it, of course, and he called Watson safe, giving Houston a 3-0 lead.

The home crowd did what any such crowd would do, booing the umpire from hundreds of feet away, knowing in their hearts he’d screwed up. This was nothing new to Tata and the umpires—the fans were merely exercising their ancient privilege. But then they heard an unfamiliar chant begin:

“Ree-play. Ree-play.”

The Video Matrix soon lit up with the slowed-down footage of the play. From Lane’s perspective (the only one he had tape of), “it was a clear out.” And clearly of interest to his viewing public. One sports editor who saw the footage said the angle Lane had, the angle he showed, “made the play look closer than it was,” suggesting he thought Tata, inches away, may have gotten it right. The crowd hooted at the footage, and Bruce Froemming turned an unhealthy shade of crimson.

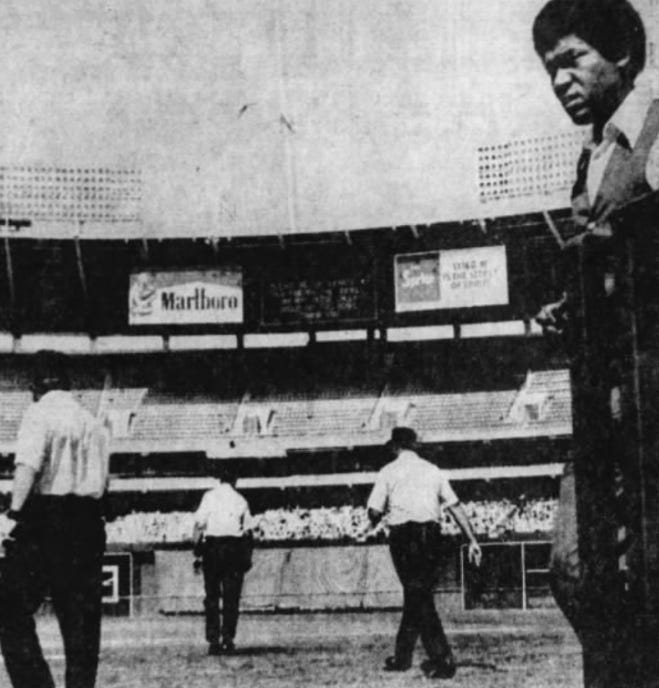

For the second night running, the crew walked off the field as jeers rained down, making once again for the Braves’ dugout and passing within earshot of Ted Turner’s personal box to share some pointed words on their way.

When the umpires found Bill Lucas, they were done asking. This time Sudol threatened to forfeit the game to the Astros (on the basis of what is unclear). The crew chief would say this was just a negotiating tactic.

“I wouldn’t have forfeited,” he said after the game. “But you have to use some psychology.”

Lucas again tried to placate the officials. The team hadn’t spent $1.6 million to demean their profession. “We got the board for the purpose of having fun for our fans, not for showing up umpires,” he said. Lucas used the dugout phone to call up to Lane, inviting the umpires to listen to his half of the conversation. “Bill used some strong words,” Froemming said, with evident satisfaction, “and got things squared away.”

The second protest in two games ended after about a minute. The umpires, who had now made themselves the unmistakable center of attention, re-took the field under a storm of boos, far heavier than those elicited by Tata’s call at home or the replay footage. Meanwhile, Lane showed off Turner’s “cool it” signage on the Video Matrix:

PLEASE BE CONSIDERATE OF OUR FRIENDS THE UMPIRES ON ANY CLOSE CALLS SHOWN ON THIS BOARD. THANK YOU.

““I knew something like this would happen,” Sudol said. “That machine is not infallible. There are too many angles.” He read from the umpires’ basic agreement, which forbade the showing of any “controversial” play on an in-park screen because of the risk of inciting a crowd. “Put yourselves in our shoes,” he told reporters. “We could have gotten killed. It’s dangerous. You get people beered up and you don’t know what could happen.”

“I’m using a director’s instincts,” said Lane. “We just try to show people what we feel they’re interested in seeing again.” Surely that play was interesting…because it was controversial.

Lane’s fellow video rabble rousers stuck up for him. If a play like that was off-limits, “we might as well shut it off and go home,” one of his assistants said. “Or we could just chase [the umpires] off for good and see if the players and fans don’t like the game better,” another suggested.

“I can understand [the umpires’] reaction,” Lane said. “It’s the first time they’ve seen it. Nothing against them, but I hate to have the board and not use it right. They shouldn’t take it personally.” Still, Lane showed at least some ability to read the room. In the eighth inning, a Braves’ runner was called out at first after bumping into Sudol in fair territory. Bristol, the Braves’ manager was duly ejected for arguing, but this time Dave Lane decided discretion might be the better part of valor. “I would like to have shown that play, but there was no way I was going to put it up there at that time.”

Lucas said the Braves would continue to work out the kinks. “We didn’t spend a million dollars just to show portraits of the players,” he told the umpires. Lucas told the same thing to the umpires’ boss, National League president Chub Feeney, when he called Feeney that night.

The next day Feeney spoke with the umpiring crew before rendering a verdict: everyone was wrong.

“I told the umpires involved that I thought they overreacted,” Feeney said. But he also thought the Watson play was “controversial,” and showing it again was potentially dangerous.

Feeney said that in the absence of tighter official rules, it was down to the team’s judgement what they chose to show, and “the Braves assured me they were not looking to upstage the umps and that it would not continue.”

In the wake of the incident, Turner, ever an acolyte of emerging technologies, could only shrug. He couldn’t blame the officials, who, he observed, were simply “afraid of the unknown.” He did, however, agree to add another person to Dave Lane’s crew. Going forward, a former minor league umpire named Hank Roundtree would decide what was “controversial” and thus worthy of censoring.

“I don’t think the umpires should be put in a position of having their judgment challenged after the fact,” Phil Niekro said. The knuckleballer hung in there through seven, and a Braves’ rally in the middle innings made him a winner. Even with Watson’s controversial run, the Astros lost, 5-4, and were swept out of town.

As were the umpires, whose crews rotated out after each series (to prevent grudges from piling up unevenly). News of the Video Matrix and the busher behind it traveled fast.

“People were talking about it when we were at the airport last night,” said incoming crew chief Lee Weyer. “You know, I don’t mind the instant replays on TV. They show we’re right more than 99 percent of the time. But it’s a little different out here. When it’s on TV they can throw their beer bottles at their television sets.”

Once Froemming was safely in another zip-code, Bill Lucas said he, too, felt the umpires had overreacted. Lucas understood the officials felt threatened by replay, but saw some hypocrisy in their response:

“One night, when an umpire misses a call, I’d like to see all the players walk off the field.”

Another episode of history rhyming, brought to you by Mark Twain and Project 3.18. You might find it depressing to be reminded that people just keep having versions of the same argument over and over, but we choose to find it comforting. Such is the clamor of progress. Only stagnation is quiet.

But seriously, give us our ABS challenge system, a-sap.

Let’s stay at Fulton County Stadium for one more week and head back to the 1990s—now that the seal’s broken we just can’t get enough—for a new installment of “What Were They Thinking??”

On June 23: “A House Afire”

If the players end up keeping ABS out, Project 3.18 feels the sarcastic head-pat should become grounds for an automatic ejection. If the owners or umpires keep it out, well, pat away, fellas.

Steinbrenner’s replay war in 1976 is a Project 3.18 story for another time.

Maybe it makes me an old fart, but I miss the old days, without all the data and video analytics, when players would just play the game.

MLB needs another Ted Turner or Bill Veeck!

Who will be the next owner with the cajones to carry the torch of creativity, ingenuity and sometimes outright insanity?