“A Cowardly and Premeditated Assault” - Part 2 of 2

A beanball in 1940 leads to a legal inquiry and a Wild-West-themed night at Brooklyn’s old ballpark.

This is the second half of our story on an attention-grabbing beaning from 1940. The characters are colorful, the game is barely policed, and the sport knows it’s too violent but isn’t quite ready to change.

Here’s Part 1, if you’re starting from the top:

As Dodger president Larry MacPhail had insisted, an ambulance took his injured star, outfielder Joe Medwick, to Caledonian Hospital in Brooklyn. Initial reports speculated that Medwick could be hospitalized for days and lost from competition for weeks, even if his skull was still in one piece.

The first physician to see Medwick examined him and assured his wife that his condition wasn’t as bad as it seemed. The doctor ordered precautionary X-rays and said the slugger would be kept overnight for testing and observation.

As Medwick was in need of rest, the doctor restricted his visitors to immediate family only...with exceptions for Dodger player-manager Leo Durocher and Larry MacPhail. This was Brooklyn, after all, and there was the pennant race to think of.

Around noon on July 19, the day after the incident, Kings County district attorney William O’Dwyer stunned the baseball world by announcing his office was looking into the possibility of foul play.

The reason I am having the matter investigated is that a story appeared in one of the papers of alleged threats by Bowman to ‘get’ some Brooklyn players. I don’t know how much there is to that. My concern is to find out if a crime was committed and, in view of the published reports, I feel I would be remiss in my duty if I didn’t look into the matter.

O’Dwyer dispatched his assistant DA, Burton Turkus, to oversee the investigation, and Turkus began immediately, aiming to do as much work as possible before the Cardinals left town the next day.

First thing first, Turkus and a police detective interviewed Joe Medwick in the hospital that evening. Despite what had been said in the elevator in the morning before the incident, Medwick told the investigators “no direct threat had been made against me by Bowman.” The victim was saying there was no crime, but the investigation would continue a little further.

“We’ll get Durocher and the three civilians who are alleged to have overheard Bowman threaten Durocher and Medwick,” Turkus said. “If we have to question the Cardinals afterward, we’ll get them when they come back to play the Giants next week.”

Ford Frick was getting baseball’s internal investigation underway that morning, not that anyone expected much to come of it. The National League president was a “get-along” kind of leader, a former sportswriter who’d gotten where he was by making friends with the owners and avoiding big waves.

“The beaning will be officially recognized by a neat report in triplicate,” Jimmy Wood of the Brooklyn Eagle predicted, “and filed away.”

This was the way it always went, Wood said. As it had when catcher Mickey Cochrane lost his career to a similar pitch. A star got brained, there was a big uproar about throwing inside, nobody ultimately did anything, and the game started down the same rutted track again.

Frick had asked to see just a handful of material witnesses on June 19, a few from each club. The Dodger contingent, small but vocal, went first. MacPhail led the conversation.

Bowman threatened to throw at Medwick on three different occasions. Oh, this whole thing is pretty dangerous, and I hope some good comes of this hearing. These feuds between clubs ought to be stopped. I think it’s a league duty to investigate the matter of helmets for ballplayers.

Durocher testified that the Dodgers were sick of being “dusted off.1”

“Our team thinks they’re being thrown at because they’re so high in the race,” Durocher said. “Reese’s beaning in Chicago was sheer accident and can be blamed on the horrid batting background—but this can’t.”

The summoned Cardinals included Bob Bowman, the accused, and St. Louis outfielder Pepper Martin, but the players had decided there was safety in numbers and most of the team arrived at Frick’s offices, ready to act as character witnesses.

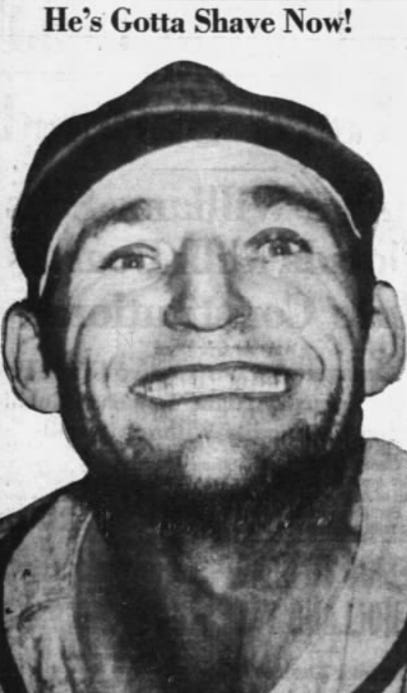

One of the first of these to testify was Martin, a “shaggy bear,” turning heads with his “beard,” a six-day effort that started when the team won on a day when he’d forgotten to shave. “I’ve been having trouble getting admitted to the hotel dining room,” Martin said, but the winning streak had been worth it.

Martin testified that Bowman had done nothing unusual. “He was just pitching high and tight. Joe wasn’t expecting it on the first ball and, unluckily, he ducked into it.”

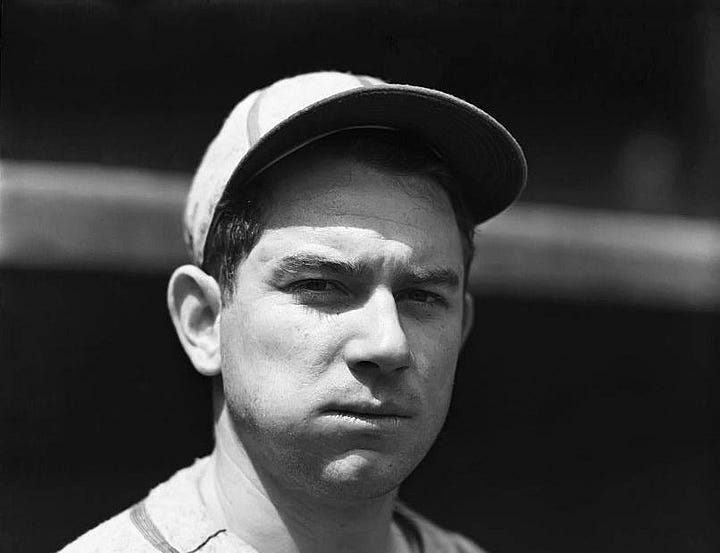

Bob Bowman, a “sharp-featured lad a little on the small side,” was appropriately nervous. One reporter went as far as calling him “surly,” because the pitcher “declined to pose for pictures and threatened to break the cameras of any photographer who took a picture of him.” He was called into Frick’s office twice.

“I supposed the headlines will come out ‘Murderer Bowman,’” the pitcher said. “I only hit one of 696 batters last year, yet they say I did this on purpose. It was an accident.”

The office area was not built to host an entire club of “husky young men,” and the place resembled an elementary school principal’s office after a food fight. Cardinals lounged in chairs, tables, and on top of filing cabinets. Others sat on the floor or stared out the window at Rockefeller Center far below.

The players made hushed small talk or pretended to read copies of the National League yearbook they found on a shelf. Some talked of the beaning (“I swear that ball went all the way out to third base.”) and there was also some interesting chatter about player safety. Brooklyn’s traveling secretary told a reporter that Larry MacPhail, was looking seriously at batting helmets.

Funny thing, just yesterday a fellow was in the clubhouse demonstrating a helmet. He put it on and invited anyone to take a whack at him with a bat. One of the coaches took a bat, wound it up, and really let it fly. It knocked this fellow clean across the room, but he just shook his head and was all right.

The players emerging from questioning were asked what was going on behind the closed door, but whatever Frick had threatened to do to anyone who broke confidentiality had been effective, and the parolees kept quiet.

Martin sat cross-legged on the floor, reassuring the younger men. “Just tell the truth,” he said. “You’ll never get in trouble for that.” At one point he led them in a soft (and tongue-in-cheek) rendition of “When the Roll is Called Up Yonder,” a short hymn about being among the saved at the time of the final judgement.

It was during the course of this interminable morning that Ford Frick learned he was not the only one investigating. A call came in from O’Dwyer’s people in the DA’s office. They’d learned where some of their persons of interest were and wanted Frick to send them over. The NL president was deeply unhappy at O’Dwyer’s involvement and refused to cooperate. “I am not working for the DA’s office.”

Frick had hoped to rule on the case by the next day but between the flood of “witnesses”—producing 32 pages of typed testimony—and the DA’s involvement, that was not going to happen.

“Hell’s bells,” Frick said. “I want to have a chance to look over everything that’s been said. Offhand, I’d say it’s not so serious as to merit the attention of the district attorney. If I censured Bowman in any way now, the DA’s office would hop on it and use it damagingly against the poor boy. I’ll wait till it all blows over.”

In referring to Bowman as “the poor boy,” it was clear which way the wind in the NL offices was blowing.

After their four-hour session in Ford Frick’s thickly carpeted boiler room, some of the Cardinals decided to head over to the Caledonian Hospital and visit Joe Medwick. The delegation was headed by Billy Southworth, the manager.

The people at the hospital didn’t want to let anyone up, but they finally let me in to see him. I was pleased to see that Joe looks all right and glad to hear that he is getting along fine. I gave him the best wishes of the gang and told him how upset Bowman was.

Bob feels that it’s bad enough to have hit a batter in the head without being accused of doing it deliberately. Especially a former teammate like Medwick who Bob feels had helped him plenty as he broke in.

What I said seemed to be okay with Medwick and I left with the feeling that there will be no hard feelings on Joe’s part.

After seeing Medwick, all but one of the Cardinals headed to work. The exception was Bowman, who’d been “given the night off,” with the understanding that he was to stay in Manhattan, safely on the west side of the East River.

St. Louis was able to run all their errands during the day because their game with the Dodgers was scheduled for that night. Night games were still a rarity in 1940, even at illuminated Ebbets Field, and this would be only the second one of the season.

MacPhail, having started the fire, now made a rather public show of trying to contain it, telling reporters he’d spent $1,700 on extra security, adding 100 additional guards. He could afford to do so. After drawing only 6,000 fans for the previous game, when Medwick was hit, the ensuing controversy had sold Ebbets Field out. Seeing the packed house, more than one scribe wondered if all the trouble was just Larry MacPhail’s latest angle for selling tickets.

The Brooklyn crowd, to their credit, was well-behaved. It might have been the extra security, or it might have been Brooklyn’s early lead as the team sought to end a four-game skid and reclaim a share of first place. The Dodgers had a 3-0 advantage in the top of the third when the Cardinals came to bat.

The Cardinals’ catcher, Mickey Owen, led off with a single. The next St. Louis batter hit a groundball to shortstop. Leo Durocher fielded the ball while the second baseman, Pete Coscarart, moved to the bag to take the throw and force Owen out.

As the lead runner, Mickey Owen’s job in that scenario was to make contact with the shortstop in an effort to dislodge the ball or prevent a subsequent throw to first and a resulting double-play. Durocher knew this routine chapter and verse, and if Owen had been his runner, the expectations would have been no different. But the Dodger manager, bruised from the first game of the series and embittered by the second, was now looking for any excuse.

“Up at Ford Frick’s office,” Durocher explained, “Billy Southworth was defending his men for the trouble the day before, and said that he wouldn’t stand for dirty baseball on his team. But on this play, Owen didn’t slide into the bag but tried to run into Coscarart, who was six feet off the bag.”

Coscarart dodged and Owen was out, but Durocher had what he needed.

I called over to Southworth, who was coaching at third base, and said, “How do you like that one?”

As Owen passed me he said, “What the hell’s the matter with you?” I answered, “Who the hell is talking to you?”

Owens turned around and charged, “fists flying.” Durocher grabbed his arms as Bick Campbell, the umpire, did his best to get between the two. Owen tried to throw a left hook past the umpire’s head to catch a piece of Durocher, but missed. The battle continued around Campbell until reinforcements arrived.

There were several smaller battles, and one eager Cardinal, Johnny Hopp, ran in so quickly from the on-deck circle that he inadvertently brought his bat into the scrum—the umpires were able to relieve Hopp of his accidental weapon before he remembered he had it.

When the parties were separated, Mickey Owen was ejected, as he’d thrown the first punch. This was considered judicial malpractice in St. Louis, of course:

Did the umpires decide that Owen caused it all and that the cool-tempered Durocher was a peacemaker at heart? Or did the fact that the game was being played in Brooklyn before those excitable Latins who live across from Manhattan have anything to do with it? We’ll have to ask Mr. MacPhail’s district attorney about that, perhaps.

Exiled to the clubhouse, Owen asked that word be sent to Durocher that he’d meet him any time, any place, to settle things. Not for nothing was Durocher called “the Lip.” He’d get the first word and the last word and when it was all over the other guy would end up thrown out of the game and still looking for more.

When the Cardinals took the field in the bottom of the third the crowd booed loudly but left it at that. For the second straight day they’d been handed a perfect opportunity to riot but politely declined to indulge, but the players picked up the slack.

The rest of the game was “as wild and whoopee as any vaudeville act ever staged.” The teams, clearly on edge, committed nine errors. The Cardinals’ shortstop, Martin Marion, made four of them, including three in one inning, tying a major league record. A Cardinal was spiked at third base. A collision at home plate led to an on-field apology—from the catcher who got run over.

Thanks to Larry MacPhail’s embrace of local radio broadcasting, Joe Medwick listened to the whole game while sitting up in his hospital bed. When announcer Red Barber signed off, Medwick’s honor had been avenged and his team had won, 8-3, putting them back into a tie for first place.

Ford Frick eventually suspended Owen for four days and fined him $50 for “conduct tending to incite disorder.” There was no better way to catch Durocher’s eye, and when the Dodgers needed a catcher for 1941, they went out and got Mickey Owen.

“There’s a thin line between genius and insanity,” Durocher once said, “and with Larry it was sometimes so thin you could see him drifting back and forth.”

After the game MacPhail made his second drift in as many days. He approached Southworth and asked him for permission to address the Cardinals in their clubhouse. Southworth agreed and presumably went off in search of popcorn.

Several reporters managed to sneak in behind MacPhail. They assumed they were going to be covering “a murderous one-man assault” on the Cardinals, but when MacPhail began speaking he sounded almost kindly, saying what a “fine, brave lot of boys” they were.

“I know many of you fellows. You’ve played for me at Cincinnati and Columbus. I’m for you and the best of luck. That’s the spirit I like. Didn’t I promise you protection here tonight and didn’t you get it?” His audience was now thoroughly confused.

“I wanted to know if any of the St. Louis players had any complaints about their treatment in Brooklyn,” MacPhail explained afterward, “and if they had any reason to think that they couldn’t play at Ebbets Field again as a visiting team. I’m darned tired of seeing Brooklyn referred to as a rowdy town.”

As MacPhail finished his remarks, their real purpose became clear:

We don’t need any district attorney’s office handling our affairs. I’ll handle ‘em.

William O’Dwyer had just lost his star witness.

The Cardinals reportedly gave MacPhail a cheer as he finished, but one account offered more nuance: “The speech ended in a patter of polite handclapping, the kind offered after an address on the care and breeding of the domestic titmouse2.”

O’Dwyer’s office initially seemed set on continuing its investigation, issuing subpoenas for Durocher, and several others to appear and give statements at 11am the next day. But O’Dwyer slept on it, and when he woke up, he had realized the Kings County DA’s office were the last remaining guests at a party where even the erstwhile host, MacPhail, now just wanted to go to bed.

Despite the pending subpoenas, O’Dwyer, “somewhat abruptly,” ended the criminal investigation, which, he announced, “had failed to disclose any evidence of criminal intent on the part of Bowman.” O’Dwyer added that he wouldn’t have entered the case in the first place if Larry MacPhail had not made such pointed accusations.

Some of the more conspiratorially minded said that “big baseball” had worked quickly to clear out the metaphorical party after seeing a public official walk in. Once O’Dwyer got started, Medwick recovered enough to hold Bowman blameless and even MacPhail himself began giving speeches to the enemy promising peace in their time.

On June 21 the Medwick Affair officially ended with a telegram Ford Frick sent to MacPhail, Sam Breadon, the Cardinals’ president, Southworth, and Bob Bowman himself:

After careful investigation, the National League office finds no proof of the charge brought by the Brooklyn club that Bob Bowman ‘deliberately’ and ‘with premeditation’ beaned Joe Medwick in the game played at Ebbets Field, June 18. The charges, therefore, are dismissed.

Joe Medwick returned to action on June 23, five days after his injury. He performed remarkably well for someone still recovering from a concussion, roping two singles in the game, but he admitted that he was far from “right,” noticing how easily he winded while running. Even minor head injuries could linger.

On the same day Medwick returned, in Manhattan, the New York Giants were playing the Cincinnati Reds at the Polo Grounds.

In the seventh inning, the Giants’ All-Star shortstop, Billy Jurges, was hit in the head by another duster. No one was subpoenaed this time, but Jurges was out for a month. It was another loss for baseball, but the grand old game brushed off the dust and went on, just as it always had.

One More Thing

On February 5, 1941, Ford Frick announced that all National League teams would test out the first true batting helmet designed for baseball. Invented by a Johns Hopkins doctor named George Bennett, Frick said the helmet was guaranteed to prevent fractures and recommended (but not required) for all batters.

Larry MacPhail was hot on Frick’s heels, announcing that every Dodger would be required to wear the new helmet, a move he’d been telegraphing for months, ever since the Medwick dusting.

Perhaps this was MacPhail’s plan all along. He’d tried yellow baseballs. He’d nearly made errant pitchers into criminals. After all that, requiring helmets seemed like common sense.

The kind of pitch that hit Medwick was so common in this era that it had a specific name, commonly referred to as a “duster,” referencing either the pitch’s knack for forcing batters to “hit the dust,” or because, when thrown correctly, the pitch would pass just by a batter, “dusting him off,” like a feather duster passing over a shelf of knick-knacks.

And I also learned that not all titmice are tufted. Thanks Paul.

The footnotes always get me. Thank you for going the extra mile (?) and providing the picture of a titmouse.