“A Cowardly and Premeditated Assault”

In 1940, a Brooklyn Dodger star was hit in the head by a pitch. The team's president shocked baseball by making an unprecedented accusation in response.

Two weeks ago we published a story on baseball’s brief flirtation with a yellow baseball, an ultimately unsuccessful innovation that sought to make the game safer for a bunch of guys who refused to wear helmets.

That story introduced Project 3.18 readers to Larry MacPhail, the president of the Brooklyn Dodgers and almost certainly our MPV (Most Problematic Visionary) for, say, 1935-1945. In addition to being a pioneer who was always willing to give baseball’s normally stagnant culture a vigorous stir, MacPhail had a particular sensitivity to “beanball” incidents, in which a player at bat was hit in the head by a pitched ball. These two qualities together made him the perfect person to champion the yellow ball and champion it he did.

In researching that story, we came across this one, which took place a few years later and cast dark shadows over the sports’ ongoing debates over player safety. At the time it was accepted that unprotected batters risked their lives at the plate, but the events of this story threatened to add a new complication: might brushback pitchers be risking their freedom by throwing inside?

Hired in 1938 to rebuild the Brooklyn Dodgers fiscally and competitively, Larry MacPhail looked at the size of the rubble pile, estimated it would take about five years to dig out, and set about the task with characteristic verve.

To cite but one example, at the winter meetings after the 1938 season, MacPhail was determined to deal but stymied by a quiet trade market. He quickly came up with an icebreaker.

“Let each club throw the name of a player into a hat,” he told his incredulous colleagues. “Then everybody digs in for a player. In that way, we do some trading.”

MacPhail got things rolling by offering a right-handed pitcher, and Bob Quinn of Boston threw in a surplus third baseman. While no others participated, two were enough to tango and the trade was shaken on. MacPhail was so pleased he said he wanted to make hat-trading an annual tradition1.

The Dodgers improved between 1938 and 1939, but MacPhail believed the rebuild would continue in 1940. “I felt that we had a club good enough to be in the first division, but not…a red-hot contender. We were looking further into the future than that.”

But the 1940 Dodgers started the season with nine straight wins and Brooklyn’s Dodger-mania switched from passive to active. “The town went crazy talking about their pennant chances,” MacPhail said. “Almost in spite of ourselves we were forced to abandon our plan to build for the future2 and shoot the works this season.”

On June 12, MacPhail shot his works, acquiring St. Louis Cardinals outfielder Joe Medwick, a six-time All-Star, 1937 MVP, and a charter member of the famous “Gashouse Gang” that won the 1934 World Series. Medwick hit the ball hard, got on base, and loved driving runners in.

The Dodgers had coveted him for several years. Brooklyn was managed by Leo Durocher, who’d become close friends with Medwick when they played together in St. Louis in those Gashouse years. Durocher was not shy about wanting to engineer a reunion, which would make their regular golf outings much easier to schedule. When Medwick held out in a spring salary dispute with St. Louis, Brooklyn’s manager opined, “[St. Louis] will have a time of it signing Ducky for less than $20,000.” Depending on one’s perspective, that remark might have constituted illegal tampering, but the Cardinals let it pass.

Medwick eventually signed with St. Louis, for $18,000, but in the first two months of 1940 some felt his heart wasn’t in his work, nor were his legs, which did not pump as vigorously as they once had. When the Cardinals faltered early, their president, Branch Rickey—MacPhail’s former boss—called the Dodger executive to tell him he was open for business. MacPhail tested Rickey’s seriousness by asking about Medwick. The response was good enough for MacPhail to hop in a plane and fly to St. Louis to continue the conversation. When the dust settled the Dodgers had acquired Medwick and a pitcher, Curt Davis, for four prospects and a large sum of cold, hard cash. As one deflated St. Louis writer put it, the Cardinals gave up their star (and Davis) “for $125,000 and a few ham sandwiches.”

Added to an up-and-coming Brooklyn team, Joe Medwick was seen as the muscle needed to secure the first Dodger pennant since 1920.

Medwick’s arrival in Flatbush came at a great time for the shorthanded Dodgers, who had been without one of their home-grown stars, shortstop Pee Wee Reese, since June 1.

In a game at Wrigley Field, Reese had been batting in the 12th inning when the Cubs’ pitcher threw a fastball that sailed inside. Reese lost the incoming pitch in the notoriously difficult background of the Wrigley Field bleachers, filled with white-shirted Northsiders enjoying the early summer weather. The pitch hit Reese in the head and he went down. His condition was initially so perilous that doctors were unwilling to make any kind of prognosis for several hours. Reese recovered, but a concussion would keep him out of the lineup for several weeks.

Medwick got off to something of a soft start with Brooklyn, notching four hits in 15 at-bats. Meanwhile, the Cardinals had not lost since their former mainstay had left town. The surging Cardinals came to Ebbets Field for a three-game series beginning on June 17. The Dodgers lost the first game, their third in a row. Medwick went 0-for-4.

Around this time, a New York Daily News writer named Hy Turkin gifted Medwick a rabbit’s foot to help change his fortunes. The lucky charm was a kind gesture, but this particular foot would prove to be defective.

The visiting Cardinals were staying in the relative calm of Manhattan at the New Yorker Hotel. This particular hotel also happened to be the in-season home of Durocher, the Dodgers’ manager and part-time shortstop. It was also where Durocher’s pal Medwick had been staying since the trade, putting both men in close quarters with their former colleagues.

On the morning of June 18, Durocher and Medwick found themselves on an elevator with several Cardinals, including a 25-year-old righthander named Bob Bowman. With Pee Wee Reese still concussed, Durocher, normally a reserve at this late stage in his career, was filling in at shortstop, and the regular innings were taking a toll. He’d been taken out at second base by a hard-sliding Cardinal the day before, and as the elevator car descended, the grimacing manager told Medwick he might take the day off.

Bowman, overhearing this, saw a chance for some lighthearted ribbing, saying, “Of course you ain’t going to play. You know I’m going to pitch.”

The remark was poorly received. Durocher reddened. “You’re pitching? Well, you won’t even be in there by the time I get to bat.”

The tone of the response must have startled Bowman, whose subsequent comment, while not unheard of, was definitely an escalation. “You both better be careful,” he told the two Dodgers. “I’ll get you both right in the head.”

This was not idle talk coming from the young Bowman, who’d already established his credentials as an “inside man.” In 1939 a high-and-tight pitch from Bowman had sent Durocher sprawling. Brooklyn’s manager had a long memory for the times he had to pick himself out of the dirt.

In the June 18 game at Ebbets Field, the Dodgers opened the bottom of the first inning with three straight hits off Bowman, scoring two runs. This brought up Joe Medwick, the team’s cleanup hitter, with a runner on first.

Medwick dug in, and Bowman uncorked a wild one that zipped inside. “I saw the ball leave his hand,” Medwick would say later, “but that was the last I saw of it.”

“I tried to put too much stuff on the ball and it got away,” Bowman said. “If I live a thousand years I’ll still think that Joe stood there waiting for the ball to curve, and it didn’t.”

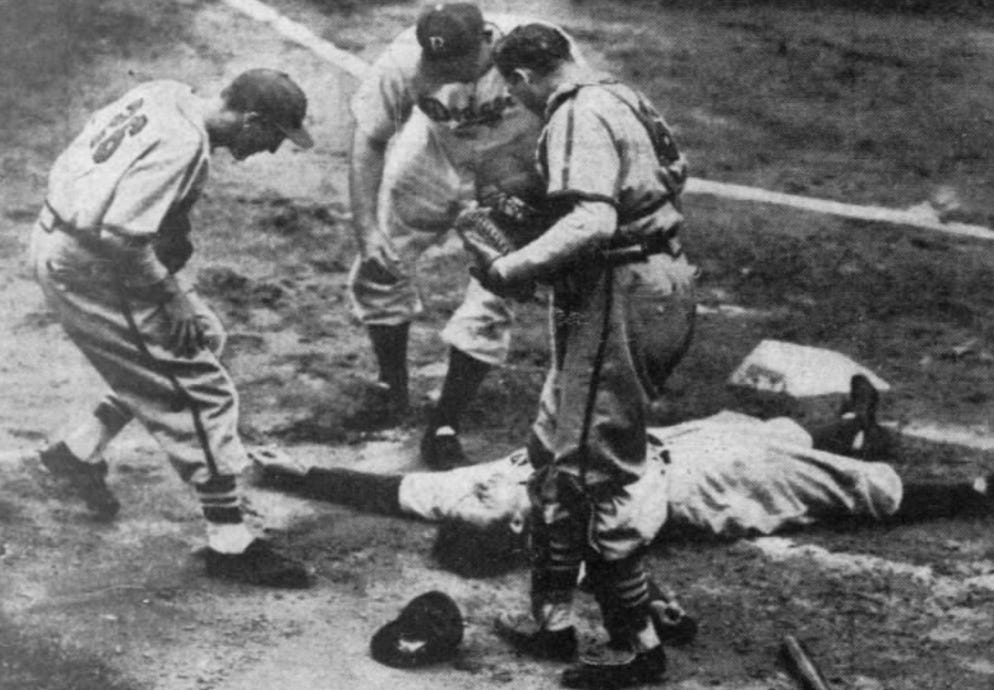

Witnesses saw Medwick jerk back and twist his head, but not in time to get out of the way. The incoming fastball struck his forehead, “right under the button of his cap.” He tumbled bonelessly to the dirt and lay almost comically sprawled out…and utterly still. In this bad situation, you hope to see the batter rolling around, writhing in pain but awake. When the downed man looked peaceful, that was worse.

Some of Medwick’s teammates would vividly remember how far the ball ricocheted off their teammate. “That ball that hit Medwick bounced to shortstop,” someone said. “[Shortstop] Marty Marion said he picked it up by third base.”

Players from both benches arrived, along with both team trainers. The crowd was hushed. One of the people in that crowd was Medwick’s wife, Isabel, who had made her first trip from St. Louis to see her husband play as a Dodger.

A doctor loosely affiliated with the Dodgers was in the stands and jumped out to perform an initial examination on Medwick, looking for "hemorrhaging or pupil fixation” that would indicate a possible skull fracture. He found neither and told the trainers to take Medwick into the clubhouse on a stretcher.

When it became clear that Medwick was alive, some of the Dodgers, still sore over Reese’s beaning, pivoted from fear to anger. One of the bench players approached Bowman, “muttering dark threats,” but the umpires successfully intercepted him.

Then came the inevitable outburst from Leo Durocher, triply angry as Medwick’s manager, teammate, and close personal friend. He made his own move on Bowman and it took both umpires and several Cardinals to redirect him.

The Final Boss of masculine posturing appeared in the form of Dodger president Larry MacPhail. He had been in the press box—no doubt at the beer bar he’d had built for the hardworking press—when Medwick was hit, but hearing what happened MacPhail made his way down to field level and emerged from the Dodger dugout roaring. Various combinations of Durocher, the coaches, and several players tried to pull him back but one by one MacPhail shook them all off and strode unencumbered across the field toward the Cardinals’ bench, ready to, as one writer put it, “set the record for high dudgeon.”

“It was the first time in my life I ever walked onto a ball field during the game,” MacPhail claimed afterward. Sometimes called the Dodgers’ chief megaphone, nearby press caught MacPhail’s every bellowed word:

Come out of there, you yellow ****!

You too, (Johnny Mize). You big, fat ****

And bring that little ****

(this particular expletive was understood to be a reference to Bowman, who, at 5’ 10”, might be considered small for a pitcher?)

You’d better come out swinging.

MacPhail then invited any Cardinal to join him “under the stands” for a frank exchange of views. Stunned, the entire St. Louis bench rose to their feet, but no one stepped forward. Outfielder Pepper Martin urged the frenzied executive to “take it easy.” When it became clear that he had no takers, MacPhail stalked off to find Medwick and the surreal confrontation ended.

Once order was restored, the umpires had a quiet word with Billy Southworth, the Cardinals’ manager. Under the circumstances the umpires recommended a change in pitchers. Southworth saw the wisdom in that advice.

Just as he’d predicted, by the time Durocher batted, Bob Bowman was long gone.

In the Dodgers’ clubhouse, Joe Medwick woke up. His wife Isabel soon joined him and as they waited for an ambulance he smiled at her and assured her he was all right. She forced a smile back.

“Wait till I see that Bowman. He’s the only Cardinal who ever throws at a batter deliberately. I’ll punch him in the face myself.” A Cardinal wife until just days prior, Mrs. Medwick knew of what she spoke.

Hy Turkin, the Daily News reporter, arrived to check on Medwick, finding the player still on the stretcher on the clubhouse floor. “Hello Hy,” Medwick said in a thin voice. “Remember the rabbit’s foot you gave me in the dugout just before the game—to change my luck? Well I knew it wouldn’t work. The rabbit had four of ‘em and they didn’t help him. Ha!”

Larry MacPhail entered the Dodgers’ clubhouse with his fire engine red hair practically on fire. Seeing Medwick awake and talking, he slowly cooled off.

“I’m okay,” Medwick said. “Let me off this stretcher. I want to go back and play.” He was keeping his body very still, however, including his eyes, and MacPhail told him he was going nowhere but the hospital.

“Take care of him,” MacPhail told the trainers. “Give him a bourbon3, if he wants it. Tell that ambulance to hurry.”

An ambulance from the nearby Jewish Hospital soon arrived, but MacPhail told them to drop off only at Caledonian Hospital, which had a brain specialist he wanted Medwick to see.

As the orderlies in white collected Medwick, Turkin watched the player run his hands through his hair, muttering to himself.

“They told me you can have bad days in a row, but I didn’t know they would pile up like this.”

The crowd that night was a relatively small one and the 6,000 Brooklynites seemed to have taken Medwick’s injury with relative grace, but Billy Southworth wasn’t a gambling man. The manager somehow secured the services of two New York plainclothes police officers, who sat down on either side of Bowman. These three sat in grim silence, watching as the Cardinals chipped away. It was 4-3 Dodgers in the seventh when word got to MacPhail that there were cops in the visitors’ dugout, and he stopped the game to complain to the umpires that the presence of out-of-uniform visitors was against regulations. This was technically true, so Southworth sent Bowman back to the dressing room, the police trailing behind him.

As the pitcher departed, Durocher fired a parting salvo. “I’ll get you back at the hotel, you bum!”

Fifty security staff were now lined up in the runways under the stands to ensure any trouble from outside stayed outside. These guards parted as Larry MacPhail, their boss, rushed past them, trying to catch up with Bowman and his escort. The 50-year-old executive lunged over the shoulder of one detective and threw a punch at the pitcher (from behind, St. Louis sources alleged). The blow dislodged Bowman’s cap, sending it spinning off like a helicopter, but the pitcher, stunned, just kept walking.

One writer said that in his behavior that day, Larry MacPhail had reached the “supreme height”—or perhaps the nadir—“of his often hysterical career.” His performance in front of the Cardinals bench amounted to incitement of a riot, and, the writer said, “I imagine a group of aroused Brooklyn fans could put on an A-1 riot.”

It was a display of vigilante justice unlike baseball had ever seen before.

Even if MacPhail thought Bowman deliberately beaned Medwick, he should not have taken it upon himself to be the judge, nor was the ballpark the proper place to be used as the courtroom.

The Cardinals kept chipping and the clubs were tied, 5-5, at the end of nine innings. It took two more innings for St. Louis to finish off Brooklyn with a two-run 11th that sealed their sixth straight win.

MacPhail didn’t see the loss. He had retreated to his office and called Ford Frick, the National League president and a close ally. He told Frick what had happened and demanded that Bowman be barred for life for deliberately hitting Medwick. Frick, taken aback and doubtlessly just trying to get off the phone, said he’d look into it.

The Dodgers’ president turned to his typewriter and furiously banged out a statement he would read to reporters after the game ended. In it, he charged Bob Bowman with “a cowardly and premeditated assault on Joe Medwick.”

Word of the elevator interaction in the New Yorker Hotel had made it to MacPhail, probably via Durocher, and he wanted to make sure everyone understood the gravity of the situation:

It’s the worst thing I’ve ever seen in all my baseball experience. This fellow came to the ballpark with a premeditated notion of committing murder and I can call six witnesses to prove it.

The Dodger president also claimed that after the beaning Bowman had told an anonymous St. Louis teammate that he had aimed for Medwick’s head on purpose and that “the [deleted by censor] should have ducked.”

It is likely that MacPhail intended all of this theater to draw attention and thereby pressure Ford Frick into a stronger response than he might have made otherwise. At worst, MacPhail might have been trying to attract the attention of baseball’s aging but disciplinarily-minded commissioner, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

“[Bowman’s] conduct represents the most reprehensible thing I have ever seen,” MacPhail said. “In my opinion he should be disciplined and the evidence is available for the competent authorities.”

“Competent authorities” was most likely a reference to Frick, but the NL president was far from the only authority in New York who read the papers, and the news the next day was plastered with MacPhail’s sensational allegations of first-degree assault by fastball. William O’Dwyer, the district attorney for Kings County, read these overnight reports from Ebbets Field with great interest.

O’Dwyer was a celebrated and fearless prosecutor who had spent the past year—and at substantial personal risk—putting away several members of a notorious organized crime outfit called “Murder, Inc.”, whose specialty was right there in the name. In matters of foul play, O’Dwyer was perhaps the most competent authority in town, and having just sent some very bad men to Sing Sing State Prison, his schedule was relatively clear.

As he finished his morning paper and digested MacPhail’s claims, Brooklyn’s DA decided to take the case himself.

In the conclusion, dueling players and dueling investigations.

Hat-trading did not become an annual tradition.

It amazes us that front-office stock language (“build for the future”) has not changed in what is approaching a century. Also: “Shoot the works” deserves a comeback.

Project 3.18 does not endorse medical advice originating from Larry MacPhail. Ask your doctor if bourbon is right for you.

Quite a tale, previously unknown to me! Enjoyed every last detail.

Great story. Imagine a GM rushing the field today to challenge the opposing team?