A Monumental Catch - Part 2 of 2

In 1908 Washington's Gabby Street did the ballplayer's equivalent of climbing Mount Everest.

Welcome to Project 3.18, a free weekly publication where a fan-first writer tells strange and surprising stories from baseball history and culture.

This is the second part of a story about dead-ball era baseball players trying to catch a baseball thrown from the top of the Washington Monument in the District of Columbia.

Here’s the first part, which covers the impressive failures of the 1800s.

In fairness to those guys, many weren’t even wearing cushioned gloves (great mustaches, though). By the early 20th century the mustaches had fallen out of favor but padded catcher’s mitts were very much in style, and it was only a matter of time before somebody tried the catch again.

As always, it started when the boys got to talking. In the 19th century these conversations usually happened in saloons or hotel lobbies, but on August 20, 1908 the fateful “bull session” took place in the Washington’s exclusive Metropolitan Club.

The room would have been filled with smoke, from cigars or cigarettes, and glasses of amber-colored liquor. We’re picturing overstuffed chairs, lacquered furniture, and luxurious curtains in front of large windows. We can hear the clink of glassware and the hum of quiet but spirited conversation from the little knots of rich and powerful men.

In one corner, a group of younger fellows were talking about the Washington Monument. It had been a few years since a professional baseball player attempted to catch a ball dropped from the obelisk’s upper reaches and it was time to—once again—argue about whether or not it could even be done.

The debate went a few rounds, building supporters on both sides of the topic, until a man named John Biddle attempted to claim the point: “No man can do it, and I’d put money up against anyone ever succeeding.”

There was a pause. Would anyone push back, or would Biddle get the last word?

“I’ll take that bet.”

The challenger was Preston Gibson, a journalist, playwright, and an avid baseball fan. Gibson was also the son of a United States senator, which was helpful to anyone who needed something from the federal bureaucracy. It’s not exactly clear how much money the two men wagered, but by the standards of the time it was probably more than most Americans made in a month.

To win, Gibson needed someone who could make the catch. “I won’t have to go far for my man,” he told Biddle and the others. “He’s here in town right now.”

Gibson would actually need two men to have any hope of winning the money (and the lifetime boasting rights). He needed somebody to make the catch, and somebody else to keep the cops away. He went to see that guy first.

Gibson finished his cocktail and made for the federal offices of the District of Columbia’s Buildings and Grounds department. He sought an audience with the superintendent of the department, who also served as administrator for the Washington Monument, a man named Colonel Charles Bromwell. With several jobs and an Army commission Bromwell was surely very busy, but he managed to squeeze Gibson in. Now, before we go further, you tell us if this man looks like someone who is likely to sign off on a novelty stunt:

It must have required some liquid courage to sit down with that man and explain what he wanted to do. But either Bromwell had a fondness for hijinks that he kept very well hidden, or Gibson, a senator’s son, was not somebody the colonel thought he could refuse. Gibson walked out of the colonel’s office with a permit allowing him to throw baseballs out of the Washington Monument in whatever manner he saw fit. When one is rich and well-connected, things just happen.

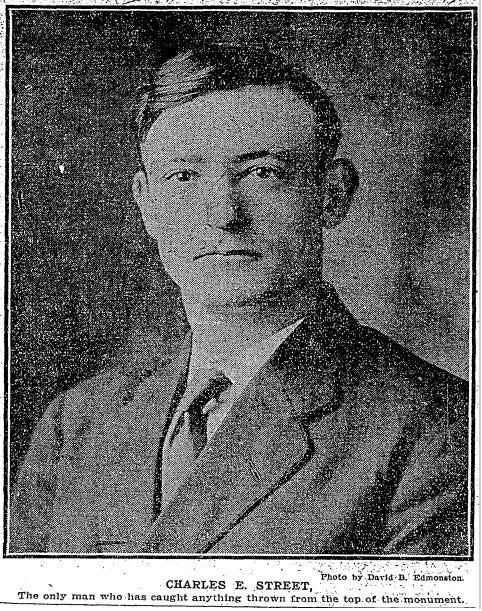

Gibson’s next stop was Washington’s American League Park, home to the confoundingly named Washington Nationals. In or around the team’s 2-0 win over the St. Louis Browns, Gibson had a chat with his man: Charles “Gabby” Street.

Street’s nickname wasn’t in heavy rotation in 1908 but it generally took over as his life went on and so we’re going to use it here. Street said a few different things about the name and how he got it, but he does seem to have been a talker. “I wasn’t the most important guy on those teams, but I was the noisiest,” he said in 1931.

He broke into the major leagues in 1904 and played about 40 games for the Reds and the Boston Beaneaters before Boston sold his contract to a minor-league club. By 1907 he was playing with the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League.

That was the year the Washington club debuted a fireballing pitcher from Idaho named Walter Johnson, and in 1908 the Nationals were looking for a catcher with receiving skills strong enough to handle him. The same scout who found Johnson recommended Street for the position and the team bought his contract.

“Walter was easier to catch than a good many other pitchers,” Street remembered. “I never saw the equal of his speed, but it was quiet speed; the ball came into your mitt with a ‘click.’ You could see it coming and you knew—if you were his catcher—where it was going to go, because he had fine control and it made nice handling. None of that wild, loud, bruising stuff.”

Quiet or loud, watching Street handle the fastest pitcher baseball had thus far produced, left an impression on people. To Preston Gibson, the man who could smoothly catch Walter Johnson was worth putting a little money on.

Street would later say he had begun thinking about trying to make a catch under the Washington Monument “from the first day I saw it.” He said he was deterred by the ordinance that levied a $500 fine on anyone caught in such a scheme. But here was a man explaining that he’d already cleared it with the authorities and offering Street $500 if he could do it. The catcher quickly agreed to try, and they planned to make the attempt the following day, August 21, at 11:00 a.m.

The next day a carload of people pulled up to the Washington Monument. This was yet another sign that there was money behind this undertaking—not just anybody had an automobile in 1908. In the car were Gibson, Street, and two other Washington players, shortstop George McBride and outfielder Bob Ganley. Gibson had invited a reporter and photographer from the Washington Post to document the attempt.

The party brought three pieces of equipment. Street had his typical catcher’s mitt, and by 1908 mitt construction had come a long way. If the ball was going to drill through Street’s hand it was going to have to penetrate 3.5 inches of padded leather first. The players had pulled together 10 baseballs to use. Gibson would have the honor of releasing them at the top. He had fashioned a seven-foot, v-shaped ramp made from two pieces of wood. The thinking was that rolling the ball down the ramp would create a more standardized descent pattern for Street to pick up on; it’s also possible Gibson simply didn’t want to get that close to the open window of the observation deck, 504 feet up. Either way, they knew the ball had to go out as well as down. The monument is 35 feet thick at the top but 55 thick at the base, so anything just dropped out the window was going to bounce off the side as it fell.

Atmospheric conditions were not ideal. It was a sunny day but the sky was streaked with clouds, pushed along by a southerly breeze. Street described the weather as “unusually windy.”

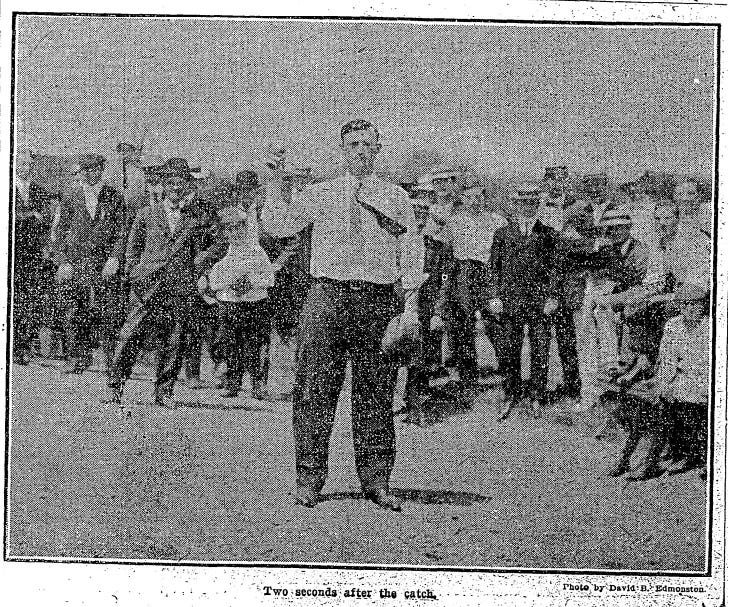

The monument itself was open and full of people using the observation deck to take in views of a kind they’d never seen before outside their dreams. There is no indication that the lawn beneath the Monument was shut down. Since the plan had not been widely announced there were no crowds—at first. The Post writer listed the early witnesses: “a few stray visitors, a couple of photographers, and the omnipresent small boy.”

Street was dressed in civilian clothes. These were fancier than you might expect for this activity, but keep in mind that casual hadn’t been invented yet. He wasn’t even wearing a hat. If not for the catcher’s mitt he might have easily been a bank teller on an early lunch break. “[Street] doesn’t look strong enough to catch a cold,” the Washington Evening Star observed.

Consulting with Ganley and McBride, he decided to take a position underneath the south-facing windows, putting the sun at his back. The players peered upward, squinting and frowning and waiting for the first missile to come shooting into the void. Only then would they know what they were dealing with.

We here at Project 3.18 don’t particularly mind heights—from above. We’ve never been inside the Washington Monument but when we go, we’ll take the elevator up and enjoy the views with no trouble. Heights from below are where we go wobbly.

Let’s put ourselves in Street’s place as best we can. It’s a windy day, we’re wearing a tie and we seem to have forgotten our hat. We’ve got an oversized mitt on and we’re standing 60 feet away from the base of an 80,000-ton free-standing rock pile. Here is the view:

Preston Gibson rode the elevator up with a carload of sightseers and a reporter. Today that elevator ride takes about 70 seconds but back then it was a 10-minute grind, and he was carrying a wicker basket with 10 baseballs nestled inside like a strange clutch of eggs. It would not have taken long before the questions started and what else could he say but the truth? After people heard what was planned, most of them would remain on the observation level, peering over his shoulder for the duration of the experiment.

There was a healthy amount of concern for Gabby Street, especially from a group of kids. As Gibson set up, one of these spotted a flaw in the plan. “What would Washington do if we lost Street? We don’t have another catcher that’s any good.”

Another youth observed that Gibson was in as much peril as Street. “It will be all over with for the guy throwing the ball if Street gets hurt. They’ll tar and feather him and you can bet it’s me that would like to light the fire.”

Gibson assured the crowd that the ant-like men crawling on the green carpet far below were professionals. He stuck the chute out of the south-facing window port and rolled the first ball down.

Street and the others waited, their hands raised instinctively over their heads, trying to shield out some dazzle and spot the ball. Ganley was the first to see it. “Here she comes!” By then it was halfway down.

As they tracked the tiny grey spot they saw the wind grab it and fling it away. Street trailed gamely behind, but he had “no play” and he stopped to watch the ball thud into the ground 30 feet away.

“The approach of the ball appeared to be in wavy lines,” Street reported, “and that motion was made stronger by the prevailing winds. I couldn’t gauge the line of flight.”

The balls rolling out of the chute didn’t have enough velocity to overcome the roiling air. “For a time it was impossible to get near the ball,” the catcher said, “which was either hitting the monument or falling so close to it that I could not get beneath it.”

Nine more balls fell to earth and Street said he wasn’t in a position to really try to make a catch on any of them. “I had always felt sure that I could catch a ball thrown from the monument, but when I failed to see the first few that were rolled I had about concluded it was impossible.”

Gibson was soon out of ammo. But with no guards or coppers running them off and a working elevator, this group had something prior expeditions did not—a second chance. Ganley and McBride suggested moving to the north side of the monument where the wind would perhaps not be as strong. The three players also agreed that rolling the balls out was no good. Someone took three or four recovered balls back up to Gibson with instructions to chuck them good and hard from the north side port.

Meanwhile, a sizable crowd had formed in a wide ring around the players. Anybody who passed by suddenly found themselves with nowhere to be, so they stood around or sat on the grass and peered upward, occasionally currying away from a windblown ball.

When Gibson threw the 11th ball it was obvious that the new plan was better. “I could see it very plainly now,” Street said. He made his first actual attempt at a catch and came close, but still a little short. The hunt was on.

On the 12th attempt he got under it. Street’s plan was to receive the ball like he would if it were any pop foul behind home plate, except with he stiffened his arms to take what he expected to be a much greater shock. It looked good, but, “I guess I was a bit timid about closing my hands on the ball.” It bounced off the outer edge of his mitt. People in the crowd clapped and the catcher was heartened. “I knew then it could be done.”

Out came lucky number 13, which might have been the last before Gibson was forced to call it a day. The ball curved and twisted, but Street was on it like a bulldog. “I realized when the ball was a hundred feet from the ground that I was going to catch it if I could get my hands on it.”

Ganley saw that this was the one. He called out to Street to brace him up. “You’ve got it!”

High above in the observation deck, people heard a “bang.” It sounded like the report of a gun.

“The ball hit my mitt with terrific force,” Street reported. “Much greater than any pitched ball I’ve caught, and I’ve caught some pitchers with wonderful speed.”

Gibson was afraid to look, but he said a quiet prayer and stuck his head out. Once he saw the scene on the lawn he turned to address the group anxiously awaiting his report.

“He caught it—I knew he would.”

Physicists estimated that the five-ounce baseball had the force of something weighing closer to 50 pounds as it neared the ground. Street was seen to “quiver” on impact, like a ship ramming into a pier. “The force of the ball benumbed my hand,” he said. It had about an eighth of the speed as a rifle bullet.

Street staggered but kept his feet. He closed his mitt around the ball and held it “like grim death.” When he’d steadied himself he opened the leather trap and looked inside. Then, according to the Post, “he laughed like a child.”

The cheer that went up from the crowd was said to have made ripples in the Potomac River.

“Didn’t I tell you Street was the goods?”

One of the kids in the observation deck was so elated that he ran the 896 steps down to the base of the monument and found Street sitting in the car looking dazed. The kid ran up to greet him. “You have the heart of a sea lion,” the kid said. “Give me your paw.” They shook hands and Street offered to get the Omnipresent Small Boy tickets to an upcoming game.

Not every fan was so easy to satisfy. One onlooker reportedly told him to keep practicing. “If you’d have thrown the ball back up again, now that really would have been something.”

Gabby Street took a brief rest at his rented room and then headed over to the ballpark to start his regular shift behind the plate. His batterymate that day was the man he’d been hired to handle, Walter Johnson. Street “played fine ball” that afternoon, showing no ill effects as he caught Johnson, the human approximation of a 500-foot obelisk.

In the fullness of time Street would eventually become known as “the guy who caught Walter Johnson,” but in the fall of 1908 Johnson was throwing to “the guy who caught the ball off the Monument.”

“It was quite a thrill,” Street remembered, later in life. “Judging the flight of the ball is the only feat. If he can do that properly, any ballplayer can catch a ball from a great height.”

The story was a sensation in the capital and the larger nation. “Fans, near-fans, and people who are not fans at all ate it for dinner, put it under their pillow, slept on it, and chewed it all over again at breakfast.”

Street had shown “an unprecedented example of clear eye, steady nerve, and cool grit.” As the first to do something, he took all the glory. Other players, led by the White Sox’ Billy Sullivan, would quickly come along to replicate the catch, but they are no more famous today than the second person to run a sub-four-minute mile or the astronauts who set foot on the moon during Apollo 12.1 Only Gabby Street made it onto The Simpsons:

After he’d done it, the Post reporter asked Gabby Street if he’d be willing to attempt the monument catch again, and he did not hesitate to reply in the negative. It had been a good afternoon; he’d made a little money and earned a little immortality, and he was happy retire as the champion. Besides, another catch would not have been the same.

The thrill had been not knowing and standing down there anyway, his glove stretched out, wondering what was about to happen.

Now he knew.

With apologies to Australia’s John Landy and astronauts Pete Conrad and Alan Bean, respectively.

Well done! And the Simpson's reference was a great touch!

Great details Paul, on a story I had read in different forms!