One Last Pitch - Part 1 of 2

After 12 years “back in the woods,” Satchel Paige returned to the majors and set a record that will never, ever be broken.

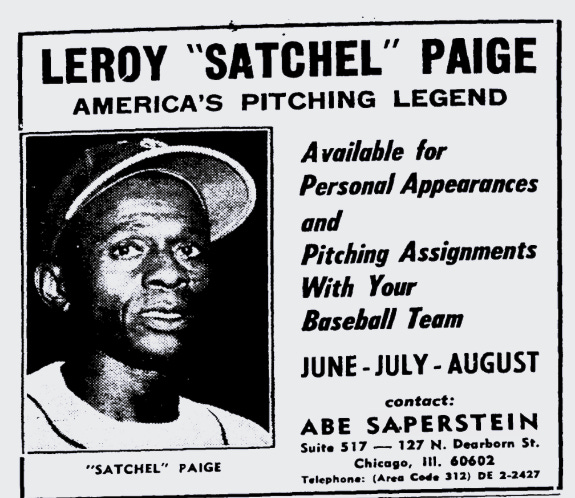

In the mid 1960s, print was still the king of sports media, and a weekly magazine, The Sporting News, wore the crown. The Missouri-based publication was part fan-digest and part industry-publication, and baseball was its chief concern. In 1965 there was no better platform with which to send a message to the baseball world, and on May 22 Satchel Paige made his pitch:

Whatever his next assignment turned out to be, it would continue a professional pitching career that had begun 39 years prior, in 1926, when Leroy Robert Paige first took the mound for the Chattanooga Black Lookouts. For the next 20 years, Paige, along with generations of Black ballplayers, starred in a segregated system. With the doors to the National and American Leagues nailed shut, some of the nation’s best baseball talent could be found in the Negro Leagues, where the level of competition was high, the resources were slim, and the recordkeeping spotty. And while Paige became one of Black Baseball’s preeminent stars, much of White America’s sporting public missed seeing his finest years, making the pitcher a living legend in the strictest sense of the term.

His accomplishments and exploits spread by word of mouth, often his own, but also by way of the people who had played with him, played against him, or seen with their own astonished eyes what he could do with a baseball. Joe DiMaggio said Paige was the best he ever faced. Bob Feller, Paige’s barnstorming rival, said no one threw harder. In his heyday in the 1930s, Dizzy Dean, a 30-game winner with the St. Louis Cardinals, told Paige together they could have won 60 games in the majors. Paige answered, “Mr. Bean (he was famously bad with names), I would’ve won 60 by myself.”

He could locate a pitch over a gum wrapper, throw through knotholes and from one end of a ballpark to the other. He could pitch in such a way that the batter would hit the ball to a spot Paige himself had selected. He famously and repeatedly sat defenders down behind him and blew away the opposition. He threw from different arm angles, doubling and tripling the number of pitches hitters had to recognize. He mastered specialized stunt pitches that few dared attempting, notably his famous “hesitation” pitch.

“The hesitation pitch is very simple,” an opposing batter explained. “The foot hits the ground before the arm comes around. It’s a delayed release of the baseball. And it would throw the timing off of the batter.” But his impeccable control was the killer, and he worked hitter after hitter, thousands of them across decades, up and down, in and out.

In 1947 Paige was 40 years old and universally regarded as one of the most accomplished and representative figures of Black baseball in the United States. He had long hoped for the chance to pitch in the integrated majors and his hopes rose when Branch Rickey, the Dodgers’ president, moved to sign a Black player. Paige’s status as an icon of the segregated Negro Leagues contributed to Rickey’s decision to pass him up in favor of a much younger man, his Kansas City Monarchs teammate, Jackie Robinson, who came without the legacy—and the baggage.

Only one owner would give Paige a chance. Bill Veeck, operator of the Cleveland Indians, had spent most of his life in baseball admiring Paige’s work and was determined to see him pitch in the big leagues. In 1948 Veeck signed Paige for the Indians’ successful pennant drive. At age 41, Paige went 6-1 with a 2.48 ERA. He appeared in 21 games, made 7 starts, including three complete games, and packed ballparks all around the circuit. He returned to Cleveland in 1949 and was used mostly in relief, but Veeck had to sell the team after the season to help pay for a costly divorce. Cleveland’s new owners did not invite Paige back.

“Unlike other ballplayers,” Veeck wrote, “Paige wasn’t granted an opportunity to pitch himself out of the league. They told him his salary was too high, that he didn’t conform to their idea of a dandy little athlete. And that was that.”

In 1951 Veeck bought the St. Louis Browns and signed Paige again. “Once again he gave an amazing display of skill, cunning, control, aplomb, etc., etc., etc.” And once again, when Veeck sold the team in 1953, Paige lost his job. That was that.

He kept on pitching, changing uniforms as easily as he changed speeds until he could claim to have “been to every town in America with 500 people in it.” The years passed and he had teeth problems and stomach problems but few arm problems. His famous right arm was still running smoothly in 1965, but he was again looking for work.

A journalist reckoned that Paige had by then earned around a million dollars in his career (as the most talented pitcher in the nation he had once commanded hefty rates to appear in exhibitions and barnstorming tours), and Paige thought that figure sounded right. But despite that seven-figure windfall the pitcher was not wealthy in 1965.

“I never could hold onto the green,” he said. “It has wings.” He and his wife Lahoma lived in Kansas City, his adopted hometown, along with seven children, the eldest of whom were nearing college-age, and another on the way. Paige had to work, but he was not exactly what the workforce was looking for. “I can’t get a regular job because they’re all so cracked up on youth,” he said. “But I can draw. I can draw 25,000 people while the big league [games] are drawing 5,000.”

These were not invented numbers. On July 2, Paige had pitched three innings for the Indianapolis Clowns, a barnstorming team that paid him $50 per appearance. For a game at Chicago’s Comiskey Park, the Clowns brought in their top draw and 21,000 people came to see him. It was their biggest night of the year. On that very same evening, in Kansas City, a game between the Athletics and the Minnesota Twins, ostensibly major-league teams, drew just under 6,000.

Now Paige was on his way north for pitching appearances in Canada and Alaska. For the native Alabamian this was far from ideal. “It’s an awful long way up there and it gets pretty cold. You see bear and moose around everywhere.”

He asked a reporter if he’d heard anything about Bill Veeck. Was he coming back to baseball any time soon? There were no indications of that. Veeck had sold his last team, the White Sox, in 1961 after a serious health scare. With Veeck on the sidelines, Paige was without a champion.

With Veeck in semi-retirement, Paige needed to find someone with similar sensibilities; someone daring enough to trust his well-conditioned right arm.

Daring—or desperate.

As Satchel Paige packed his bear-spray, the annual Baseball Hall of Fame festivities were kicking off in Cooperstown, New York. The mid-1960s were a lean time for the Hall, which, despite supposedly being for “all of baseball,” had not moved to welcome any of the retired Negro Leagues greats who could have kept induction season hopping for many years. Instead, in 1965 the Hall was preparing to welcome James “Pud” Galvin, who was both eminently deserving and 63 years deceased.

Bill Veeck had seen this show before and he hated it.

“Every year along this time, I get mad,’ he wrote in a nationally syndicated column. “Not irate, annoyed, irritated, or choleric, nothing high class. I just get plain mad.”

He wanted other Americans to be mad, too. Mad at the Hall, searching under the couch cushions of the 19th century while the best pitcher of the 20th century, very much alive, went unrecognized; and mad at the baseball establishment that still refused to give Paige the opportunities he deserved. Even as he approached 60 years old, Veeck was certain Satchel Paige could still make a key out or three for any major-league bullpen.

In case they’d missed the tiny item buried in the Chicago Tribune, Veeck informed his audience of the Clowns exhibition at Comiskey Park, in which Paige had pitched three scoreless and tallied three strikeouts. More importantly, just the chance to see him pitch had filled half the seats in a major-league park. The Chicago exhibition ruined any claim that Paige was ineffective or too expensive.

A job, Veeck said, would help Paige in more than one way. Despite being both the oldest and most prominent pitcher in the sport, baseball’s decades of segregation had kept Paige out so long that his big-league career ended 60 days short of the five years of service time he’d need to receive a major-league pension.

Many baseball owners thought Veeck was a trouble-maker and a rabble-rouser whose ideas demeaned the game, but Charles O. Finley, owner of the Kansas City A’s, saw Veeck as a patron saint, and what Veeck admired, Finley admired. In mid-September, Finley echoed Veeck’s message and described Paige’s outing for the Clowns as both impressive and disappointing.

“It’s too bad,” Finley said, “that Satch has to run around in exhibitions like that. The major leagues should find a place for him. There should be a place in the majors for Satch.”

Paige had been on Finley’s mind all year. When the pitcher and his eldest daughter had sent letters of inquiry to every major league team at the start of the season, Finley had been the only one to write back.

Charlie Finley had owned the Kansas City Athletics since the very end of 1960. He inherited a team that was for all intents and purposes the sidecar on the New York Yankees’ motorcycle, and remaking the A’s had proved much harder than Finley expected. He had now owned the team as long as the previous derelict owner had, but Finley’s A’s, by winning percentage, were slightly worse than the Yankee-ravaged teams that preceded them.

Kansas City’s A’s finished last or next-to-last in nine of their first 11 seasons, and two nascent expansion teams, the California Angels and the Washington Senators, had already surpassed the A’s, a franchise in its seventh decade. The 1965 A’s had been earmarked for 100 losses from the get-go and were well on their way back to the American League basement by September. Saddled with another bad team, Finley focused on giving people other reasons than baseball to come out to Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium.

1965 was the year he introduced Charlie O, his beloved mule mascot, who remained with the team longer than any A’s manager and longer than most of the players. A mule didn’t quicken many pulses in Missouri, a state with deep roots in agribusiness, but Finley loved Charlie O so much he got the mule his own air-conditioned travel trailer and rode him into hotel lobbies. He also brought the mule into any stadium where the host club would let him inside1.

A real animal lover, Finley set up what the A’s advertised as “the only zoo in the major leagues” behind the stands in left field. The rather grim facility was home to rabbits, pheasants, peacocks, some particularly discombobulated monkeys, and a dog named Old Drumm. Old Drumm was a working dog, assigned to accompany the grounds crew when they raked the infield mid-game, but on several occasions he “refused to leave” and “had to be run down.” An American League umpire, of all people, was enlisted train Old Drumm in the off-season.

The owner threw Day after Night trying to draw crowds. There was Camera Day, Family Day, Bat Day, Scouts Night, Automotive Industry Night, Senior Citizen Day, and dozens more. Farmers Night was a particular success, drawing 25,000 people. But mostly the A’s promotions just seemed desperate and rote, and the team was on track to draw a dismal half-a-million fans for the season, the worst showing since they arrived in Kansas City. “It seems Finley has promoted everything,” one nonplussed local writer observed, “except the best gimmick of them all—a winning team.”

On September 8 Finley enlisted the A’s 23-year shortstop, Bert Campaneris, in a novel stunt in which “Campy” would perform at all nine defensive positions in a single game. Campaneris finished his rounds successfully but, we have to say, was no Shane Halter out there. He dropped a fly ball in right field, gave up a run while pitching, and even bore the brunt of a home plate collision while catching in the ninth inning, suffering bumps and bruises that would keep him out for the better part of two weeks. Still, “Campy Campaneris Night” helped a team with a 51-87 record draw 21,000 people, the fourth-best crowd of the season.

Finley realized that “event” promotions had more drawing power than discount tickets for niche audiences. A ticket to see something unique had briefly brought desultory Municipal Stadium back to life.

Campaneris Night made up his mind. The owner picked up the long-distance telephone he used to run the A’s and called for Satchel Paige.

On September 10, the A’s held a press conference to announce that Satchel Paige had signed a major-league contract covering the remainder of the 1965 season.

“I thought they were kidding,” Paige said of his signing. He and Finley had come to terms over the phone; he would earn $4,000—the equivalent of $40,000 today—for his two-week stint with the club.

As it always did, the media conversation turned to Paige’s age. His true age and his date of birth had been something of a running joke for several decades. Born on July 7, 1906, he was 59 years old, which reporters gently reminded him of as he signed his A’s contract.

“Who did the research on that?” Paige said. “Whoever he was, he knows more than I do. I’m a shade over 50. I think I can still pitch and help this club,” he said. “So what difference does it make what my age is if I can [pitch]?”

Finley called in from Chicago and said that he hoped to keep Paige on the A’s roster long enough to reach his five years of service time and the commensurate pension. He also promised that Paige would pitch in the major leagues before the year was out:

We’ll start Paige on his “Appreciation Night,” September 25, and we’ll have other features centered around him. We aren’t helping him, though, as much as he’s helping us. Paige’s name is one of baseball’s greatest, and still has its magic.

Paige was asked if he could pitch before September 25, and he gave it some thought. It had been 12 years since he’d thrown a major-league pitch. “I’ll need a few days to get in really good shape,” he concluded. “Then I’ll do whatever the manager says.”

The manager, Haywood Sullivan, was with the A’s in Baltimore. He learned he had a new player via the Orioles’ manager, Hank Bauer. Once Finley did get in touch, Sullivan had no comment on Paige’s signing, other than to confirm that he would make one start.

At first the players assumed it was just a joke, or a publicity stunt, but the team’s public relations manager came to the clubhouse to confirm that Paige was really joining their club and the goal was to help him get his pension. But would he really pitch? The players knew enough about their boss to question his methods.

“Charlie Finley and Ringling Brothers would have gone well together,” A’s pitcher John O’Donoghue recalled in 2025. The owner would have taken that as a great compliment. He welcomed comparisons to P.T. Barnum, founder of the “Greatest Show on Earth.” Bill Veeck had been the first so-called “Barnum of baseball,” and while he was on the shelf Finley was eager to claim the mantle.

Where Charlie Finley fell on the spectrum between Barnum and Veeck was an open question in 1965, but he continued to follow an extremely Veeckian blueprint as Paige prepared to don the green and gold.

Inspired by Veeck’s decision to give Paige his own monogrammed lounge chair in St. Louis, the A’s owner took a double-size old rocking chair from his Indiana farm and had it reupholstered and refinished for Paige to sit in during games.

Veeck had enjoyed closely adhering to the letter of the law while mocking its spirit, and Finley made a big show of getting special permission from the American League to allow Paige to sit (in his rocker) outside of the A’s bullpen. This was ostensibly at Paige’s request. The bullpens in Kansas City were dug about four feet into the ground, and the aged pitcher apparently didn’t love the symbolism. According to Finley, Paige’s sentiment was, “I’m close enough to below the surface as it is.”

Ever accessible in his Maryland retirement, Paige’s former patron applauded Finley’s move, while taking care not to get too close to the man who seemed obsessed with borrowing both his material and his reputation.

“I just hope they use Leroy right,” Veeck said, “and give him a chance to show what he can do and qualify for the pension. I’m certain Charles Finley wouldn’t sign Satch just to pitch one night and capitalize on his ability to draw a crowd. He wouldn’t want to embarrass Leroy.”

Veeck was not at all worried about Satchel Paige embarrassing himself. Paige had nothing he deserved, but everything he needed:

Shut out of the Hall, shut out of the majors, [he’s] still throwing the high hard one, the hesitation, the cross-fire, and the new curve—still throwing them all exactly where he wants them.

Many people doubted the pitcher, but these were often the same people who’d never seen him pitch. Veeck had seen enough of Paige to make him a believer for life. He knew the legends were true—and still being written.

Next week, Paige returns to action and adds a remarkable line to his Hall of Fame plaque.

On October 13: “Into the Light”

And on Clear the Field, our new podcast…

New episode up! Ted and I talk forfeits, minimalist writing (not mine, of course), and debate the merits of 19th century baseball names. Give us a listen on Substack or wherever you listen to podcasts.

The White Sox were among the teams that refused Charlie O (the mule) entry, and what Finley did in response is a story we’re saving for another time.

Wait . . . the founder and first coach of the Harlem Globetrotters was Satchel Paige’s agent? As always, the excellent writing is accompanied by compelling photos.

What an amazing pitcher, and even more so, still pitching at 60. I’m glad he lived to be elected into the HOF! Such an interesting profile; can’t wait for part 2.