Eliminated (and Loving Every Minute)

With nothing left to play for, these teams just played.

As we reach the close of the baseball season, two emotions rise above the rest: excitement—and relief. For the playoff-bound, the end of the season has a thousand purposes, but for early-eliminated teams September is a limbo. Next year can’t come until this one mercifully ends.

Most “lost” seasons end with a sigh and a whimper, but every so often a season bound for the dust heap ends with something special, a last, defiant flicker of spirit. Today we’re honoring a few favorite flickers.

Have a Day, Shane Halter (2000)

When Detroit Tigers utility player Shane Halter woke up on October 1, 2000, he had no idea that the sun had risen on the best day of his professional life. And maybe his entire life.

It was the close of the 2000 season, and Halter’s Tigers were finishing the year with a shrug of a game against the Minnesota Twins at Detroit’s Comerica Park. Halter had worked hard and without ego all year, appearing in ⅔ of the Tigers’ games and showing great positional flexibility. He could play anywhere, and he had. There were no awards for that kind of usefulness, but Halter deserved one just the same.

For all intents and purposes, the Tigers’ season had ended the day before, when a walk-off victory over the Twins finalized Detroit’s 3rd-place standing. With that settled, the Tigers’ first-year manager, Phil Garner, decided to use the last game to honor the player who’d done it all for Detroit that season. When Halter arrived at the park Garner told him where he’d be playing that day—everywhere.

“I didn’t want it to be a joke,” Garner said. “I wanted people to have fun with it. Shane has played all these positions before and played them well—he deserves to be in the record book.”

Garner was not a showy leader, and he kept the plan quiet. The crowd of 28,000 was not told ahead of time. All they knew going in was that Shane Halter would be the day’s starting first baseman. Then, in the second, he shifted to third base. In the third he moved to right field. That was when the crowd really figured out what was going on, he said. “That got my adrenaline pumping.”

The tour continued across the outfield and back into the infield at shortstop. In the seventh inning Halter donned catching gear and replaced Brad Ausmus to catch reliever Billy Patterson with the score tied, 8-8. It was a long inning for the battery and Patterson gave way to Nelson Cruz, but Halter remained behind the plate as the Twins scored three runs to pull ahead.

In the eighth inning Shane Halter made his pitching debut. It was the first time since 1931 that the Tigers used a position player to pitch.

“He stunk,” the pitching coach said. “Couldn’t throw strikes. No movement. He did get ahead of one hitter.”

Halter faced just that one hitter, Matt LeCroy, going ahead on strike one and then throwing four straight balls. He was moved to his last stop—a familiar perch at second base—and into a very small club.

Just three other players in NL/AL history had done it, all in September. Bert Campaneris was the first, in 1965 (Kansas City A’s owner Charlie Finley was involved, naturally). Next came César Tovar for the Twins in 1968. Most recently, the Rangers’ Scott Sheldon had done it, just a few weeks prior to Halter. But nobody had done it like Shane Halter did it, pairing an elite defensive accomplishment with a career day at the plate.

In the third, right fielder Shane Halter singled and scored a run. In the fourth, center fielder Shane Halter hit into a double-play. Left fielder Shane halter bailed him out in the fifth when he hit a 2-run single. In the eighth, Shane Halter, the catcher, hit a 2-run single of his own to cut the Tigers’ deficit to two. In the ninth, with the score tied, 11-11, second baseman Shane Halter hit a deep drive to left field and approached nirvana.

When I first hit the ball I thought I was going to hook it around the foul pole and it was going to land in the camera well for a home run. That would’ve been the topper of all toppers there.

The ball bounced off the wall for a single, but two batters later Halter got to cross the plate to seal the Tigers’ walk-off victory. It would have to do.

“I don’t think we’ve had a better ballgame all year, in terms of excitement and emotion,” Garner said. He and the Twins’ manager had combined to use 42 different players in the contest, tying an American League record. Seven different Tigers played multiple positions during the game, and Brad Ausmus1, the Tigers’ catcher, made his career debut at two different infield positions to help Halter pull it off.

It had been a long, dispiriting season. But the sun was shining, the Tigers had won, they had swept, and they’d given the fans an unforgettable game. Many of the players took off their jerseys and handed them off to fans near the dugout. Hopefully whoever got Shane Halter’s jersey got it signed.

He went 4-for-5 (tying his career-best) with three RBI and two runs scored. Of the five players who have “played the field,” no other offensive performance compares. “It was a magical day,” Halter said.

Especially with the way the fans got into it and the team coming back to win. Until you’ve actually played the game and see how fast-paced it is, you have to admire the guys who have played all the positions in the past. It was an honor that Phil gave me that chance.

It must have been as fun for a manager as it was for the player at the center. By the time it was over Garner’s lineup card resembled Beethoven’s sheet music. “I had the umpire so confused I could have done anything I wanted,” Garner said. “I was confused, too. But actually it worked out perfectly, right down to the last guy.”

“Bargain Day” (1920)

Even when you are all the way out of it, there are circumstances in which the end of the season still creates urgency. Such was the case in 1920, when the Pittsburgh Pirates, with four games left to play, were still in a liminal space between fourth place and, possibly, third.

Their place relative to the podium would hinge on the outcome of a final three-game series against the team they were chasing, the Cincinnati Reds. If the Pirates won each of those games, they had a shot at third. The series was to begin on Thursday, September 30, but a rainout forced a doubleheader, to be played on October 2. But Forbes Field was wet and on October 1 winter came early to Pittsburgh, and the teams could not play “because they did not possess earmuffs, fur coats, and other necessities to protect them from the chilly blasts,” resulting in yet another postponement.

But where to put this displaced game? October 2 had already been double-booked, and after that the Pirates had to leave for a tedious one-game road trip to Chicago, the last game of their season. They could always just cancel the game, but the sticking point, as always, was money.

The rules at the time assigned each club a portion of the profits from the World Series. Each team would receive a cut based on their regular-season standing. The third place finisher would earn more than the fourth place finisher, and if the Pirates didn’t win four more games, they would have no shot to finish in “third-place money.”

The Pirates complained to the team’s owner, Barney Dreyfuss, and Dreyfuss, a true man of the people, approached the Reds’ manager, Pat Moran, with a creative proposal: On October 2, “let’s play three.”

Moran thought Dreyfuss had lost his mind, dismissing the idea outright and saying “it was too much on the boys” to play three games in one day.

Dreyfuss tried another tactic. He recalled a 1916 doubleheader in which the first game finished as scheduled, but the second game went 18 innings. “That isn’t any worse, is it?”

Moran had nothing to gain by agreeing. “Well, I am against it and will not play unless compelled to.”

That could be arranged.

Dreyfuss picked up the phone and called the National League president, John Heydler, to make his case for a tripleheader. Heydler said he would think it over and send a telegram with his decision. That night both teams received the same message: Game one to start at noon, games two and three to follow—at 10-minute intervals.

It had been done before. Twice, in fact. The first time was in 1890, when Pittsburgh played three against Brooklyn and lost them all. It happened again in 1896, when Baltimore swept the Louisville Colonels. But even to the people of 1920, these earlier instances were “belongs in a museum”-level history. Heydler might not have even been aware of them when he made his decision.

The Reds were understandably “in an ugly humor” over the tripleheader, but they were stuck. If they didn’t participate they’d lose by forfeit and the Reds’ owner would face stiff fines. They would play, but Moran declared “not a chance in the world” that the Pirates would catch them.

The weather on October 2 was frosty but clear and 8,000 masochistic baseball diehards filed in for the Pirates’ “Bargain Day” festivities. One ticket, three games. BYO thermal underwear.

The Pirates opened with their ace, Wilbur Cooper, a 24-game winner, hoping for a strong start. But the Reds were doubly-angry. Not only did they have to play three games, they were also getting a lot of questions about a breaking story in Chicago, reporting that the White Sox might have thrown the 1919 World Series as a part of a gambling conspiracy.

The Reds insisted they would have won regardless and took their frustrations out on Wilbur Cooper, who lasted just over two innings and “was glad to escape with his life.” 27 innings were to be played that day, but after just three the Reds led, 8-3, and the question of third-place money seemed settled. The 13-4 final score made it official.

But that still left two bleakly meaningless games to play, and the few thousand remaining fans bore chattering witness to “loose work” by both teams, featuring “crazy quilt” lineups of bench players and bulk pitchers. These liberated men were “glad of the chance to work off their rust,” but everyone else was freezing and miserable.

The Reds won the second game, 7-3, and as the sun dropped in the west in game three the Pirates salvaged something for dignity, taking a 6-0 lead after five innings of play. The Reds offered to concede the game if it meant they could leave, but the umpire, Hank O’Day, swore he could still see and feel his hands. By the sixth inning it was near 6 o’clock and even O’Day was overcome. He ended the game early and not a soul in the park protested.

The tripleheader was a bold move, but six straight hours of baseball proved that “too much is too much,” the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette wrote, and such marathons were “not likely to be copied extensively” in the future.

In fact the unusual arrangement was never seen again, and as the players had a union with which to stand up to this kind of exploitation, tripleheaders were effectively banned.

Baseball Burlesque (1902)

1902 counts as “modern” baseball, but just barely. This was just the second season the American League had operated as a major league, and the very-junior circuit had only recently decided that, henceforth, foul balls would count as strikes.

There was no postseason of any kind in 1902. The first modern World Series (in large part the creation of Pittsburgh’s Barney Dreyfuss) was a year away, so all that anyone played for in 1902 was their place in the standings.

On Sunday September 29, the top two spots were already decided: the Philadelphia Athletics won the pennant, and the St. Louis Browns came in second. This was a fine showing for the newly incarnated Browns in their first year in St. Louis.

The runner-up Browns were finishing their inaugural season at Sportsman’s Park, facing the Chicago White Sox (or the White Stockings, their given name). It was a doubleheader day, and when it began, the White Stockings’ position in the standings had not yet been finalized, and in the first game both teams played it straight.

In front of 16,000 people, one of the largest crowds of that inaugural season, the Browns manufactured a run in the bottom of the ninth to break a 9-9 tie and win. The White Sox’ loss settled their place in the standings. No matter what happened in the second game, they would finish in fourth place.

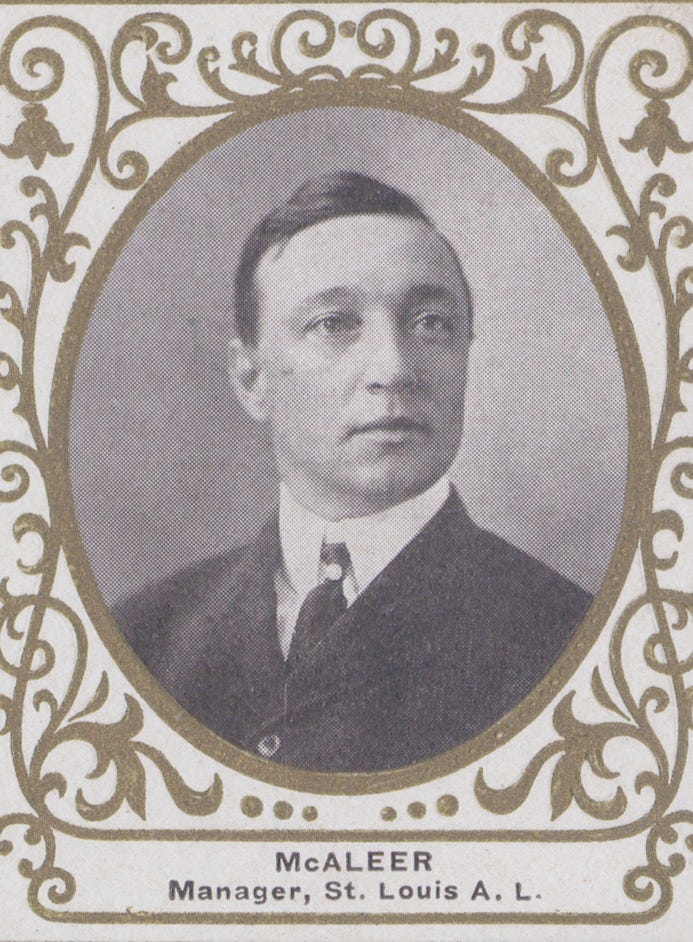

The Browns’ strategy for the second game probably came from the manager, Jimmy McAleer. At the very least, McAleer was a co-conspirator. Either way, handed a pointless game, McAleer decided to push the futility to its utter limit.

McAleer’s strategy seems to have had two main points. Firstly, no one regularly used as a pitcher would pitch; and second, no one would play their regular defensive position. The batting order was described as “a mixed pickle lineup,” as random as if it had come out of a hat.

Now, we could tell you who played where and who hit when, but, honestly, this is baseball so far in the misty past that it didn’t mean much to us to learn that, for example, Bill Reidy played left field, of all places, so we’ll spare you the minutiae.

But imagine how fun it must have been for the fans who did know what a regular Browns’ lineup looked like (and who the team’s actual pitchers were) when the announcer rattled off a lineup so nonsensical it might have come out of a Lewis Carroll poem.

The resulting game was “a burlesque,” a parody of baseball in which “hilarity reigned” and everyone reveled in the total abandonment of norms.

The White Sox got into the spirit quickly. One of their infielders “did stunts” in the outfield, and the first baseman cracked everybody up by “wearing a sweater of a hue that would have insured him a job as a matador at a bullfight.” That’s 19 words to tell you the sweater was red.

The Browns’ five pitching “recruits” had their ups and downs. Bill Friel’s appearance may have meant the most, as his four innings of work meant he’d played every position for the Browns at least once during the season. He held the White Sox scoreless for three but took a “larruping” in the fourth.

His replacement, Jesse Burkett, a left fielder by trade, insisted on working up an elaborate system of signs for his only career pitching appearance. Despite looking like “a mud turtle 50 miles from water,” Burkett quite enjoyed himself and even managed to throw an “in-drop” that observers said any professional pitcher would be proud of.

The White Sox delegated their pitching duties to just two players, neither of whom were pitchers. Frank Isbell started things off, with Sam Mertz catching him, but after an inning they decided to switch places. According to newspaper accounts the two continued switching off, trading “slow balls,” that were pretty effective. Only one swap is reflected in the official records of the game, but all records of this vaudeville show must be taken with a grain of salt: the scorekeeper reportedly “threw up his hands in distress” after three innings of play and sat back to watch.

Incredibly, only one of the seven “pitchers” used that day gave up a base on balls, and despite the lack of professional batteries there were no wild pitches or passed balls. Even stranger, this “free-hitting fun-maker” of a game, which Chicago won, 10-4, took just one hour to play.

With that said, the ending was a little truncated. With two outs in the ninth inning, Bill Reidy prepared to take the last at-bat of the season but never saw a pitch. The rope lines holding back thousands of standing-room fans came down and people were everywhere on the field, amongst the players, and in the dugouts. Police were helpless to move the crowd and the umpire “quickly called the game.”

Hmm, “quickly called the game,” with hundreds of people on the field…

Was that…a forfeit?

By the rules used in the National League, this should have been a forfeit, but this was the American League and in the spirit of the day we’re not even going to attempt to look those rules up for our purposes here. In any case, the Browns took a plain old “L” on this one.

There was a “rush” for the St. Louis bench, and the crowd “carried off every bat in sight” as souvenirs, but this was a great sign, according to R.L. Hedges, the team secretary:

Everybody wanted to shake hands with the heroes of the hour, and the club is minus several bats, taken as souvenirs by the enthusiastic crowd. The American League, it appears, has finally made a conquest of the town.

What a great mentality. Glory is rare and fleeting, but fun is lying all over the place waiting for somebody to pick it up. Just two years into “modern” baseball and here was a great template for enjoying a meaningless bit of September. Sometimes life hands you cucumbers, yes, but that’s a chance to make some pickles.

Baseball loves and respects its history, and the end of a long season is often when we pause and say goodbye to players who made that history as they prepare to step into the ages.

But sometimes—if the September conditions are just right—the great ones come back.

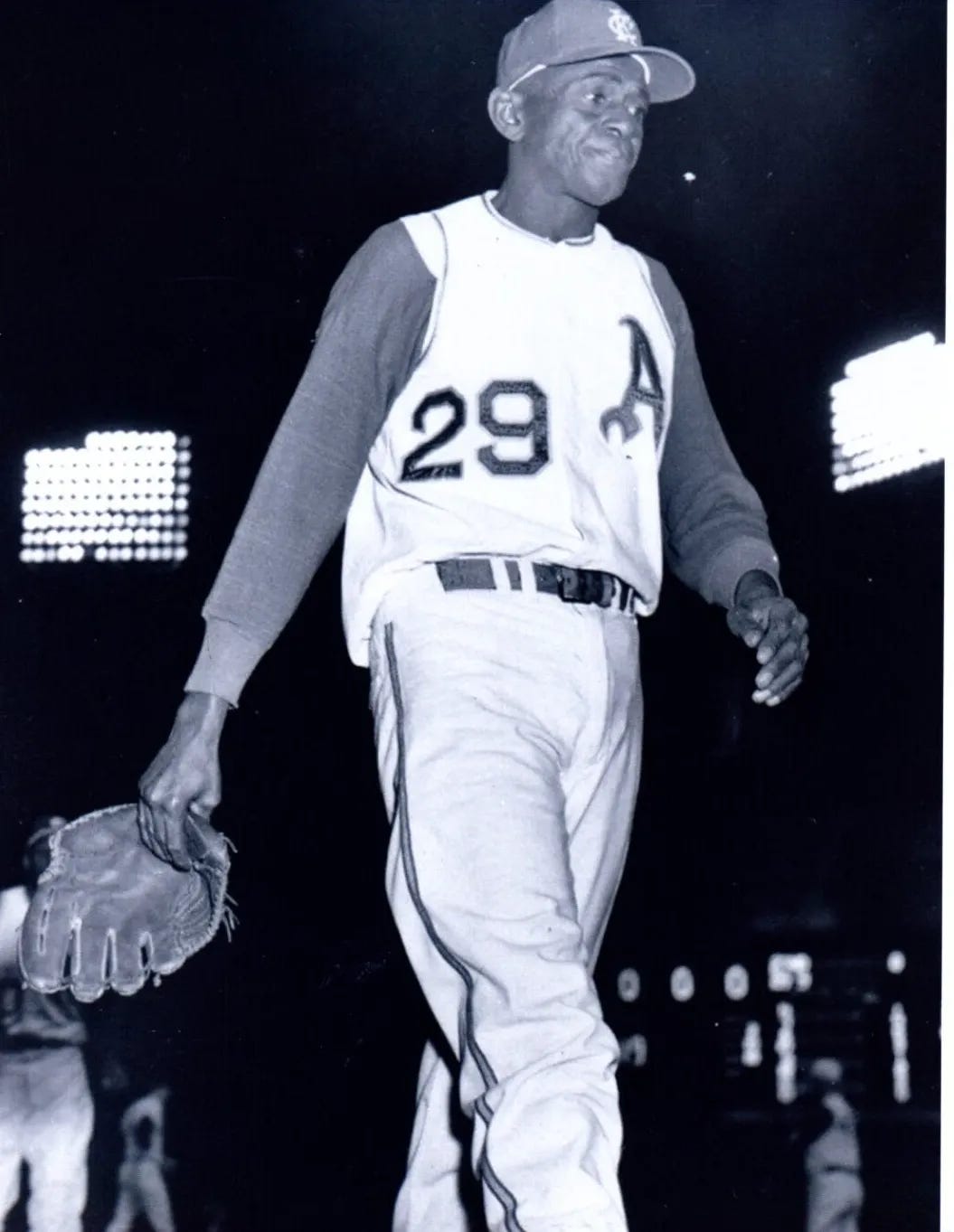

On October 6: “Satchel Paige Appreciation Night”

On September 30, 2017, Detroit’s Andrew Romine became the fifth player to play all nine positions in the same game. The manager who made that happen for him was Brad Ausmus.

Any article that starts off being about Shane Halter is an article I'm going to read. Thanks for helping me relive that memorable game!

It occurs to me that "Baseball Burlesque" was the very first "Bat Day" event - a grand tradition, which is, alas, no more.