Never Late for Supper - Part 2 of 2

Once the players’ strike ended, Dick Allen began an MVP season, found a measure of peace, and brought thrills to Chicago.

Before we were so rudely interrupted by a 53-year-old work stoppage, we were talking about Dick Allen’s arrival on Chicago’s South Side. Following his stormy seasons in Philadelphia and two years of being passed around, Allen agreed to give the White Sox a chance…and vice versa.

Here’s the first part of our Allen story:

And the little labor interlude:

In happier times, the Chicago White Sox expected about 50,000 people would come out for Comiskey Park’s opening weekend, originally scheduled to begin on April 6, the second day of the pre-strike season. The players’ strike wiped out that series and the one after, costing the White Sox alone an estimated $300,000. Remember that the strike began when baseball’s 24 owners refused to pay some $400,000 into the players’ pension fund.

Until there was something worse putting in its place, the White Sox left the signage advertising the defunct home opener up on the front of Comiskey Park. It was a forlorn reminder that business had butted in to spoil everyone’s fun.

The negotiated ending of the strike discarded all the unplayed games. Teams would simply pick up the original schedule from April 15 onward. This crude resolution robbed several teams, including the White Sox, of an opportunity to begin the season at home, which was a special kind of crime, as one writer noted:

Openers were the one day teams could expect a big crowd without having to give something away. The fans actually come for the baseball, not to get a helmet or a poster or a seat cushion.

The Texas Rangers had it the worst. The club had been moved from Washington (where they were the Senators) in the offseason and had been scheduled to start their inaugural season with two series at Arlington Stadium. Both of those series got wiped out, so fans in Los Angeles and Chicago got to see the Rangers play before anyone in Texas did.

As teams across the country prepared to face the fans for the first time in the strike, it was very much an open question what kind of reception they’d get. “In the heart of the true fan, the love of the game has always been there,” one writer said. After the strike, “maybe things will change.”

The White Sox would have to open their season on the road, in Kansas City. In yet another show of the kind of petty disunity that burned them again and again, the owner of the Royals, Ewing Kauffman, announced that he would formally protest all three games against the White Sox in response to Sox owner John Allyn allowing his team to practice at Comiskey Park during the strike.

Before the opening game, the Royals’ general manager, Cedric Tallis, presented a letter of protest to the chief umpire, saying Allyn’s move “created an unfair competitive advantage during the first few games of the resumed schedule.” The letter asked the American League to forfeit all three games of the series to Kansas City.

The umpire, Jim Honochick, dutifully pocketed the letter and then twirled his forefinger in a signal to proceed anyway. The time for paperwork was over.

We’ll never know what kind of dilemma the protest letter might have posed for American League president Joe Cronin, because the White Sox went ahead and lost all three of the disputed games au naturel.

The White Sox played rusty. There was no clutch hitting. In the opener the Sox had nine men on base in the first three innings and only one was brought safely home.

The Royals’ pitching was better, they produced timely hits, and their clean play made Ewing Kauffman look like a clown. It was probably the only time a series sweep has embarrassed an owner.

Dick Allen was the Sox’ only bright spot. He played a flawless at first base and had five hits in the series. He hit a ninth inning home run in the opener and a game-tying ninth-inning double in the finale. A few feet higher and it would have been a game-winning three-run homer.

Allen’s performance indicted the whole concept of spring training. His teammates, had trained for five weeks and looked in need of at least two weeks more. But Allen, who had “trained” for perhaps 10 days, was the only White Sox player who looked sharp.

“He has the quickest bat I have ever seen,” third baseman Bill Melton said of his new teammate. “He takes the ball right out of the catcher’s glove and he’s swinging a big-ounce bat. His timing is still not there but he’s hitting the ball anyway. I couldn’t believe it. All he wants to know is what each pitcher’s out pitch is. That’s all he cares about.”

With a series under their belt, the White Sox players had a little more insight on their new teammate, and they began an apparent competition to say the nicest thing.

Melton was the reigning home run champ in the American League and probably benefited more from Allen’s presence in the lineup than anybody, so he had a lot to say:

He is going to lead this team. He is super. I think everybody on the club is going to look up to him. Before the first game in Kansas City he went around and shook each player’s hand and wished him good luck.

Melton found Allen to be a vocal presence, in contrast to his tight-lipped reputation.

What surprised me was the way he yelled on the bench, encouraging guys, cheering them. Usually some guy who comes over from another ball club isn’t like that at first, especially a super star. There is no doubt in my mind he is for this team first.

The strike-driven schedule changes created another small piece of history. For the first time ever, a Chicago team was going to open their ballpark with a night game. Chuck Tanner announced that Wilbur Wood would start for the Sox.

Wood also started the first game in Kansas City on April 15, pitching nine innings and giving up only a run before finally yielding to a reliever as the game went into extras. Pitching the home opener on April 18 meant Wood was taking the ball on two days’ rest. Today this might seem like some sort of horrific oversight, but in 1971 and 1972, this was the way Wilbur Wood liked to pitch.

Wood was an effective left-handed knuckleball reliever in the second half of the 1960s, but Chuck Tanner and his influential (and perhaps mad) pitching coach, Johnny Sain, transitioned Wood to a starting role in 1971. The change worked out immediately, but Sain was just starting to cook. That May, confronting slim pickings in the Sox’ starting rotation, Sain proposed that Wood pitch one one fewer days’ rest, half the time. Wood agreed to try it.

For two seasons, Wood essentially brought Deadball-era pitching into modern baseball. He worked on two days’ rest 14 times in 1971. Out of 42 starts, he won 22 games. Wood pitched 334 innings1 with an earned run average of 1.91. He would have been the most valuable player in baseball except for the fact that Fergie Jenkins was a better hitter.

Yes, throwing the knuckleball puts far less stress on a pitcher’s arm, but let’s not discount the challenges. The knuckleballer is like an artist chiseling a sculpture out of marble. The work required enormous concentration and patience, and making a mistake usually meant instant disaster.

In 1972, Wilbur Wood resolved to spend even more time in the studio. He made four starts in just 11 days to start the season and gave up just a single run. Johnny Sain was Frankenstein, and Wood was his monster.

“Really,” the monster said in 1972, “a lot of other pitchers could work on short rest if they tried.” The arc of history disagrees.

Like Melton, the Sox’ pitching star was eager to give Dick Allen an early vote of confidence. Asked if Allen was the “individual-first” player he was often made out to be, Wood frowned. “Dick an individualist? I know this is not so. Why, he’s one of the greatest guys in this room right now.”

But what about all the contract holdouts, missing team activities? Wood said Allen shouldn’t be penalized for that:

Each man does it in a different way. [Contract negotiations] are a time when he has to go out and fight for himself, for what he thinks he’s worth. It’s something you have to do. I’ve held out three or four times myself. Sometimes you have to fight for what you think is right.

Allen was who he was, Wood said. And that was what made him great. “He plays ball the same way he negotiates. He gives 100% all the time.”

The accidental opener was played on a raw springtime night in Chicago. 21,000 hardy fans braved the cold to see Dick Allen’s Comiskey debut. That was less than half of a full house, but it still felt like a hot crowd. “20,000 White Sox fans make noise like 40,000 in any other park,” Johnny Sain said.

That crowd booed the Rangers during their introductions, with two exceptions. The Rangers’ first manager (a holdover from the Senators) was none other than Ted Williams, who could get applause going to the grocery store. And Williams’ coaching staff included Nellie Fox, a legendary White Sock2 from the 1950s. Comiskey gave Fox a long standing ovation.

The huzzahs continued as the White Sox were introduced, with hearty cheers for Melton, Wood, and Dick Allen. There was no hint that either Allen’s holdout or the players’ strike had left anyone on hand with sour grapes. The atmosphere was so electric, one columnist wrote, “even Marvin Miller probably would have been applauded.”

And so began a night of pure happiness for Chicago. Williams sent a lineup of eight righties to face the lefthanded Wood, but there’s a level of talent where strategy becomes meaningless, and Wilbur Wood was living up there. He pitched a three-hit shutout, facing only 28 batters (two of the three Rangers who reached base were erased on double-plays).

On offense, the White Sox scored five runs before the hapless Texas pitcher, Bill Gogolewski, managed to record the first out. Dick Allen was in the middle of that delightful sequence, working a walk and setting up Melton and left fielder Carlos May behind him, both of whom drove in runs. Poor Harry Caray up in the announcer’s booth was a broken record: “Holy cow! Holy cow! Holy cow!”

Later in the night, Allen added a single and a two-run RBI double. The four hitters around him in the lineup had 12 hits, and the team added four runs in the fourth inning and five more in the fifth. Rangers center fielder Joe Lovitto spent half the game chasing hard hits. “I just measured my calf muscles,” Lovitto said, “and they’re three inches bigger than they were when the game started.”

It was a 14-0, 15-hit party, utterly lacking in suspense, but fulfilling a Sox fan’s every wish. “Nobody was really surprised they put on a show like this tonight,” Johnny Sain said. “That lineup is too powerful. There will be other nights like this. And those fans will have a lot to talk about. They are the most enthusiastic I’ve ever seen.”

The enthusiasm that night was such that it nearly cost the White Sox the game.

It started with one, as these things almost always did. One fan in the outfield in the ninth inning, hopping down to make the rounds and shake hands with the Sox outfielders. In the booth, Harry Caray was appreciative, and his words may have encouraged some copycats.

“All I did,” Caray said afterward, “was say that he looked like a nice young guy who just wanted to shake hands with his heroes and I didn’t see anything wrong with that.”

The one became a dozen, and each encouraged a dozen more. “All over the lot there were youngsters, teenagers, and teeny-boppers,” “a bunch of overeager college kids in the annual rites of spring.” The Sox appeared to have a youth movement on their hands.

The game was briefly delayed, and Tanner had fears of a 14-0 victory becoming a 9-0 forfeit loss.

“I’m sure the umpire would have waited a long time before doing anything as drastic as that,” Tanner said. “But I was worried about it for a minute.”

The home plate umpire asked the White Sox public address announcer to direct the fans back into their seats, and the fans, bless them, did as they were told.

“It could have been an ugly incident,” one local writer wrote, “similar to the riot at Wrigley Field on opening day a few years ago. Fortunately it wasn’t, perhaps because the mood was one of frivolity or perhaps because, since no attempt was made to apprehend the interlopers, there was no one to riot against.”

After the game, the Rangers players that stuck around managed to tip their cap to their tormentors, Wilbur Wood in particular.

“Boy, he was tough tonight,” slugger Frank Howard said. “If you can keep it tight, say within a run or two, you can force him to go to his fastball more, but with a five-run cushion to work with in the first inning, he knuckled that thing up at us 90% of the time.”

Wood had been taught the art of the knuckleball by the great Hoyt Wilhelm, who impressed upon his student that a wise man threw the knuckleball always—or never.

Manager Ted Williams had no comment on Wood’s performance—literally none, as he had fled the Rangers’ dressing room and left the ballpark before the press corps could walk down from the upper-level press box. It fell all the way to the Rangers’ traveling secretary, Burton Hawkins, to give a comment.

“They’re not really that good and we’re not really that bad,” Hawkins assured reporters. The arc of history disagrees.

The next day, Chuck Tanner was still “tingling all over” from the win. He’d helped build a good White Sox lineup in 1971 and now, with Allen, he seemed to have a great one.

“Dick is our leader, no doubt about that,” Tanner said. “We have a lot of great players with spirit and drive. But the day Allen finally showed up in camp, you could tell the difference. His arrival had an impact on the other guys, just as did that highly vocal opening night crowd. I’ll tell you, when our guys came out on opening night and got a standing ovation from 20,000 people, I got a lump in my throat.”

Tanner promised a summer full of tingles. “This team is just like a college team. It has that same kind of spirit.”

The result was an exciting brand of baseball Chicago fans were buying. For a second straight year, the Sox had outdrawn the Cubs in opener attendance.

“I think I’ve found myself a home,” Dick Allen said. “Yes sir, I think I have. I think I’ve found a place where I’m really wanted.”

The home opener was the first time Allen, a National League lifer to that point, had ever set foot in Comiskey Park. Asked what he thought of one of baseball’s oldest palaces, Allen had only one note. “The lights are a little dim,” he told reporters. But not to worry: “When I was a kid, half the time the electricity was off.”

The White Sox swept the short series with Texas and then repaid the Royals’ earlier sweep with one of their own. Completing their fifth straight victory, Dick Allen singled and scored the winning run, coming a double short of the cycle, with two runs driven in. He was batting .452.

Chicago was filled with talk of Allen’s exploits—and the name he’d asked to go by. “I made up my mind right then and there,” he wrote in his autobiography, Crash, “that Dick Allen was going to pay back Chicago for the respect they were giving me.”

It was a thrilling week. The White Sox won seven straight games, four by a single run. Allen was in the middle of everything, hitting well over .400 as the calendar approached May and talking up how much he loved the Sox’ young players. It was a performance that extinguished all doubts.

“I thought the club was getting a raw deal,” one fan said of the Allen trade. “I still have reservations, based on his past. But, looking at it as a life-long Sox fan, it’s obvious he also has the potential to be the best hitter they’ve ever had.”

“Sure, [the fans] love him,” another fan said. “But if they can’t fall in love with a .441 hitter, they can’t love anything.”

Throughout his career, Allen’s talent on the field never seemed to be enough to win fans over, but hitting safely in eight straight games seemed to do the trick in Chicago. The cheers were a little bewildering.

“This is a different kind of attention for me,” he said. “I’ve always had the other.”

A reporter asked Allen if he planned to forgo his hard batting helmet when playing first base at Comiskey.

Smiling, he shook his head and snapped his fingers. “Success can go faster than it came.”

Without his incredible 1972 season in Chicago, Dick Allen probably isn’t elected to the Hall of Fame in 2025.

37 home runs. 113 runs batted in. 99 walks. A .308 batting average. A perfect 1.000 fielding percentage (no errors). Allen played in 148 out of 154 games and if not for the games lost to the strike, his cumulative numbers would probably have been even better. It was the best season of Allen’s career and the best season by any position player in the American League in 1972, a performance that earned him the Most Valuable Player award.

After being named the MVP, Allen was asked what he’d be looking for in a new contract. He grinned. “I don’t know. How much do you have?”

He and the White Sox agreed on a three-year, $700,000 deal, no holdout required.

Next week, we’ll check off another of our Year Two resolutions and tell Project 3.18’s first story from the 1990s! Regular readers know this is about a decade beyond our comfort zone, so we’ve picked an irresistible topic.

On April 28: The Last Forfeit in Baseball History

One More Thing

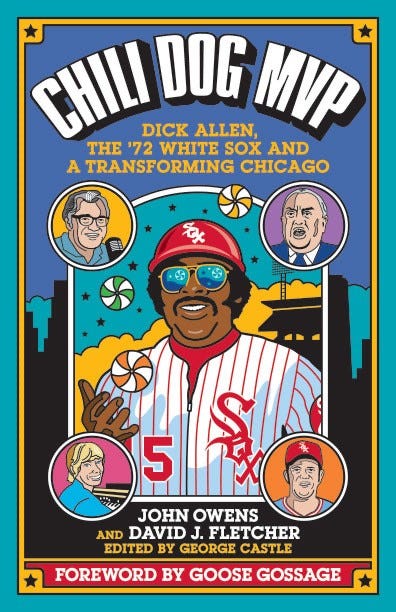

If you’d like to learn more about Dick Allen’s 1972 season with the White Sox, check out the definitive work on this topic:

Chili Dog MVP, by John Owens and David J. Fletcher

(Not a sponsored link; we just liked the book!)

In 2024 Logan Gilbert led all pitchers by throwing just 208 innings, and we should all be very worried about him as a result.

We know “White Sock” is not the proper way to identify an individual Sox player, but we’re doing it anyway and you are invited to join us.

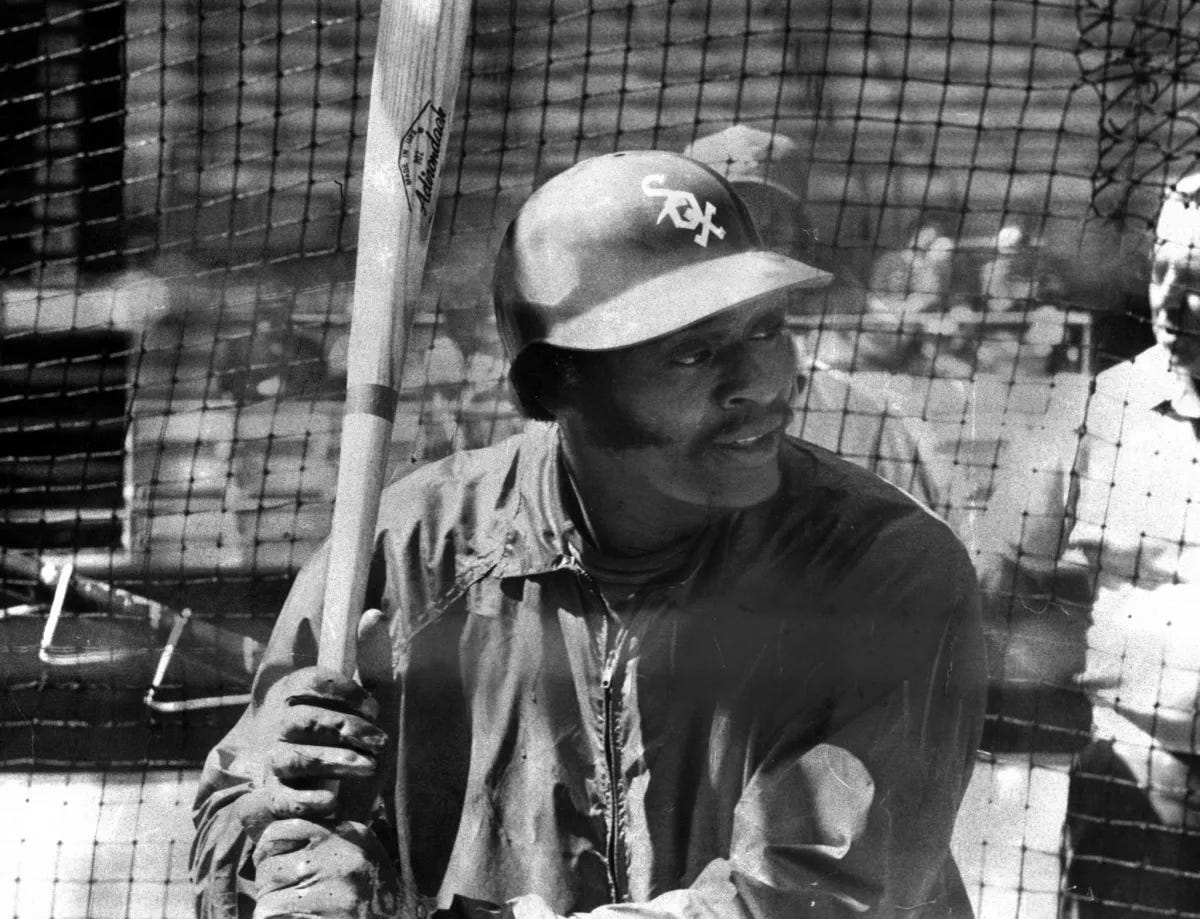

Dick Allen was definitely a legendary White “Sock,” for sure! If I didn’t already know this all took place in the early 70’s, the photo of Dick Allen with lamb chop sideburns confirmed it! Another interesting post, Paul.

I approve of your “White Sock” creation, Paul - it beats “White Stockings” or “Pale Hose.” One of my favorite White Sox players from that era was Walt “No-Neck” Williams.