Packed House

A gorgeous spring day. A simple misunderstanding on the field. Seat cushions. The perfect recipe for a baseball forfeit.

Happy New Year, everyone! We hope you’ve been able to enjoy the holidays and have much to look forward to as the calendar turns. As always, Project 3.18 is here in your inbox to temporarily crank said calendar backwards, for purposes both informative and entertaining.

It has been a while since we have covered a baseball forfeit. Regular readers know we’ve made it our semi-regular mission to chronicle these misadventures from baseball history, which so seldom get their due.

So how about we start the new year with a new forfeit? They say hindsight is 20/20 but surely even people at the time could see that this1925 game wasn’t going to end well…or at all.

On April 26, 1925, 44,000 fans, reported to be “the largest crowd that ever saw a baseball game in Chicago,” descended on Comiskey Park.

In its 1925 configuration the ballpark at 35th and Shields only seated some 30,000 people, but in these carefree times, fire codes were more like general suggestions, and standing attendees were regularly admitted by the thousands for big games. 44,000 attendees suggests a Very Big Game Indeed, but we can’t quite figure out what the draw was.

The White Sox were 8-5, hardly taking the American League by storm. Their opponents that day were the 8-3 Cleveland Indians, but nothing was really at stake so early in the season. As far as we can tell there were no memorable debuts or retirements or anniversaries or career milestones reached. For Chicago in April it was a glorious day, with clear skies, light winds, and temperatures in the mid-70s at game time. On such days Chicagoans hurry out of doors, dazed and pale, grinning at each other like freed prisoners of war.

Let’s briefly consider two prior record-setting Comiskey games. The park probably had its first 40,000+ crowd in 1913, when the White Sox shrewdly threw a “Frank Chance Day” to recognize the beloved former player-manager of the Cubs, who had been traded to the AL New York Yankees. Chance’s return drew 42,000 well-wishers. Many were probably Cub fans, but the Sox were happy to take their money all the same. That record was threatened 10 years later, in 1923, when 41,000 fans attended the Sunday finale of the annual crosstown exhibition series with the Cubs.

Could a really nice day in April 1925 draw more people than these earlier, more evidently crowd-pleasing events? Anywhere else, certainly not, but in Chicago…maybe.

But something drew them—like never before. Three hours before the game a long line for tickets snaked around the park. By 1:30 pm every available seat had been sold. Period accounts say Comiskey could seat 34,000 people, while modern numbers say even less, but either way, 30 minutes before the first pitch the stands were jammed and overflowing. The park gates were ordered shuttered, but people kept pressing downward toward the field, and some in the front rows began pushing out past the low infield barriers to gain relief—and a better view. When the game started a crowd reportedly 40 people deep extended from the Chicago dugout, down the left field line, around center field, and into right field. Eventually some 8,000 people were estimated to be crowded around the playing field perimeter.

The grounds crew improvised , stringing a sturdy piece of rope in front of the trespassers in the outfield. Games had once routinely been played this way, with an accompanying ground rule: a ball hit into the crowd counted for two bases.

Before the first inning began there was another mass breakout that briefly delayed things getting underway. In short left field a small contingent of blue-coated police yielded to “several thousand” more fans who decided to stand behind third base. Like superfans at a concert, their standing forced most of the patrons in the front rows of seats to stand in order to see anything, leading to some hard feelings.

There wasn’t much worth seeing, at least for White Sox fans. The home team never led and they could do very little against Cleveland starter Sherry Smith. The Indians fared much better against the Sox’ starter, Hollis Thurston. The carefully groomed Thurston gave up nine hits in four innings, earning his ironic nickname, ”Sloppy,” at least for the day.

Thousands of people continued arriving at Comiskey Park well after the game started—Daylight Savings, a relatively new phenomenon in 1925, had begun in Chicago overnight, but many people did not get the memo on that change until they arrived “early” for a game that was actually underway. In the sixth inning several thousand shut-out fans reportedly tried to break through an entrance to the bleacher section but the Chicago police “rushed three patrol wagons” of officers to the park. “Many of the entrance stormers were taken downtown to see what a desk sergeant looks like.”

By the late innings it was 6-1 in favor of Cleveland. With the game proving uninteresting and a natural rivalry forming between the sitting fans and those standing out on the field, some fans began making their own fun, employing that secret ingredient of so many ballpark debacles: the seat cushion.

Regular readers know of Project 3.18’s fascination with the ballpark seat cushion, a long-gone fan convenience which seemed to encourage all kinds of mischief in the first third of the 20th century. Seat cushions had already caused more than one forfeit but they remained a part of park life at Comiskey in 1925. These cushions were apparently square and made from dark-colored leather, but we don’t know what they were stuffed with and we still don’t know whether they came with your seat or whether you had to rent them from the park as an add-on.

We certainly know how bored crowds often returned cushions—by flinging them out onto the field, particularly in the direction of someone they were unhappy with, such as the standees who’d forced them to also stand in order to see anything of the game. Several cushions now flew. The umpires and police officers fixed their best glares and things settled down, for the moment.

Each team added a run, but the game remained just as out of reach for Chicago, and in the ninth inning many more fans succumbed to the temptation of the cushions. In particular, “the boys from the stockyards” who were doing most of the throwing “brought up their big guns and started bombing in earnest.” The game was delayed for 10 minutes as the crowd, “possessed of a holiday spirit,” engaged in a massive pillow fight.

“Cushions began flying from all directions. The air was black with them. It looked like snow in Pittsburgh.” Cleveland’s third baseman, Freddie Spurgeon, and the umpire on that side, George Hildebrand, found it rather hard to concentrate as they ducked cushions that “came ripping from the stands.”

The umpires loudly warned the crowd of a forfeit and the cushion battle was halted enough to let play proceed, though “order was never fully restored.”

With conditions deteriorating, both teams made “heroic efforts” to quickly end the game amid flurries of Pittsburgh snow. The plan seemed to be to get the ball to one of Cleveland’s surest defenders, Joe Sewell, at shortstop. The White Sox’ monosyllabic outfielders, Bibb Falk and Roy Elsh, hit weak outs to Sewell as a cushion bounced off umpire Hildebrand’s head and another grazed Spurgeon’s chin.

With two outs, the last White Sox batter was third baseman Willie Kamm. The teams ran the same play one final time; Kamm hit a weak ground ball to Sewell, who made another sure throw to first baseman Ray Knode. This is perhaps Ray Knode’s one moment of historical significance so let’s pause for a moment and wonder whether the “K” is silent.

Baseball Reference has him as “Ray,” but his real name was Robert and his listed nickname was “Bob,” so do with that what you will. Contemporary accounts all called him Bob, except the snide Chicago Tribune writer, James Crusinberry, who insisted on calling him “Young Mr. Knode” and seemed to resent the fact that Knode went to college.

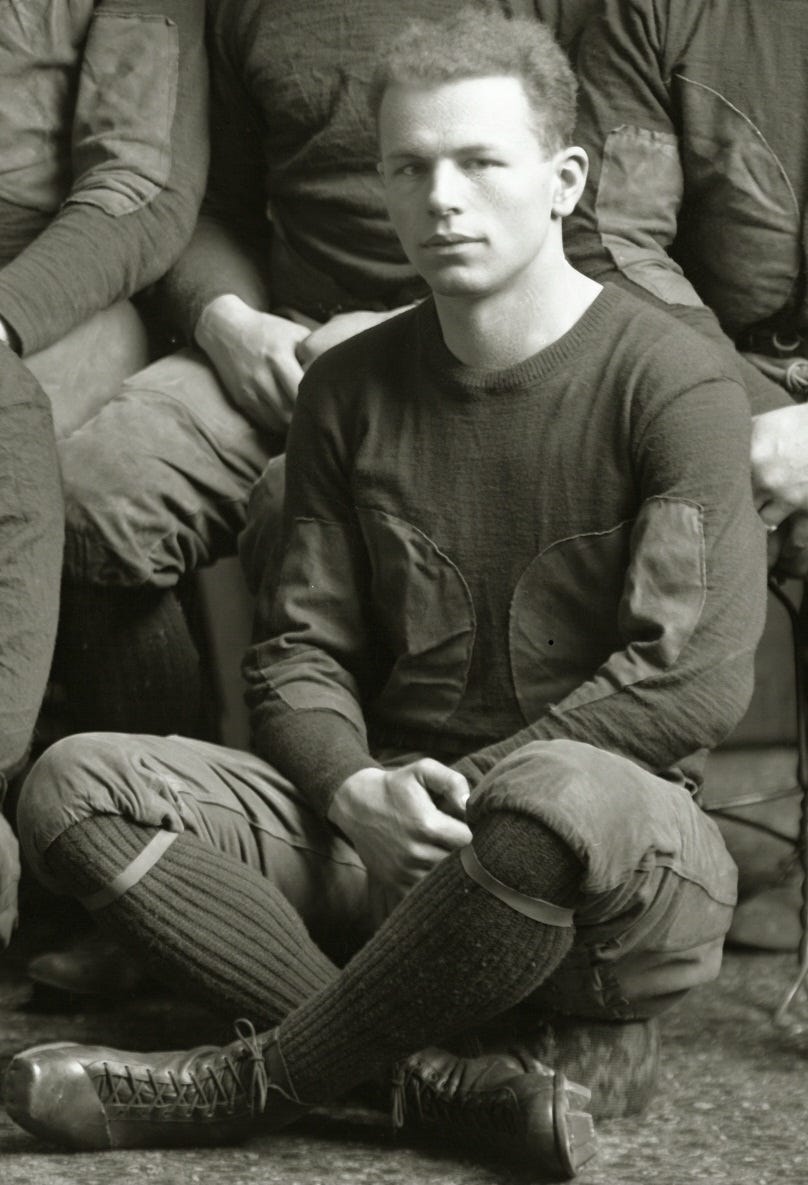

Knode was 24 years old in 1925, and this was perhaps his best and last chance to stick in the major leagues. He had signed with the Indians in 1923 but was still much better known as the former University of Michigan quarterback, in 1921 and 1922.

After going pro Knode spent two seasons in the minor leagues, getting a late season call-up each year. In 1925 he received the chance to break camp with the Indians and potentially stick on the roster. Knode played exclusively first base and here is a little scouting report, delivered in the daffy Shakespearean parlance of the times:

Bob Knode not only can massage the apple but he is an unusually clever doorkeeper. A year ago during the early part of the campaign he was in front of the parade with the wagon tongue. Although he naturally slumped when the Barons turned up their toes to the daisies, the one-time football gem finished the campaign with a .295 mark and occupied a prominent perch in defensive play.1

This was a big moment for Knode, as Cleveland was sitting their regular first baseman, George Burns, to give the younger player a full nine innings. Knode drove in two runs on a fielder’s choice and a groundout, but also had one error and was caught stealing. We imagine Burns wasn’t feeling particularly worried about his job security before the ninth inning, and after the events of that inning he could rest easy.

Willie Kamm’s soft ground ball found Joe Sewell. The shortstop’s throw came in and by every account it was “perfect,” a chest-level dart that came right to Bobby Ray Knode. Accounts vary as to what happened next. The majority of reports say that Knode received the throw with his back foot several feet off first base.

“He stabbed with one foot here and with another foot there,” according to the Tribune, “and then rolled in the earth, frantically searching for the bag.”

But the primary Cleveland account says that Willie Kamm had “jostled” Knode as he ran through first base, causing the first baseman to drop the ball.

One of these accounts is entirely wrong. If Knode was two feet off the bag it seems impossible that Kamm could have bumped into him. And if he was jostled and dropped the ball he would not have been rolling around in the dirt looking for first base.

Either way, Knode was almost certainly distracted, because out of every player on the field he had the best vantage from which to see several thousand of the standing room fans crowded along the third-base side now running his way.

Hundreds of people had began running as soon as Sewell released his throw. “They thought the game was over,” Crusinberry wrote, “but it wasn’t, because Young Mr. Knode evidently failed to learn while at Michigan just exactly where the bag is located at the first corner.”

A more pragmatic umpire might have considered the score, the circumstances, and the tide of onrushing humanity and decided, “close enough,” ruling Kamm out and the game over. But that wouldn’t do for umpire Billy Evans, who made his exacting fraternity proud that day. He’d seen no out recorded, and he signaled Kamm was safe at first. Not that anyone in the herd was paying attention.

The players reportedly tried to stay at their positions on the field, but soon between 8,000 and 10,000 fans had joined them there. “Within a few minutes the playing field was a seething mass of milling, mauling, tugging fans. The players were engulfed in the streams of humanity and swept along with the tide.”

135 police working the game were also being swept along, while a squad detailed to traffic duty outside the park tried to push their way inside. The overall police response was described as “half-hearted,” but we think that’s unfair. There was not much for them to do; the crowd was in good spirits, with no obvious troublemakers to remove, and pushing back a mob this size would have been like trying to empty Lake Michigan with a bucket brigade.

The Indians’ player-manager, Tris Speaker, pushed his way towards the infield, “looking like a cork bounding on a restless sea” as he shouted to the umpires that the game should be forfeited to his team so everyone could leave. Knode and Kamm, aware the game wasn’t over, gamely held their positions at first base, each no doubt waiting to take advantage if the other broke and ran.

The umpires came together. The crew chief, Clarence “Pants” Rowland, was a former White Sox manager, and he seemed to be reluctant to end the game arbitrarily, but the three officials agreed there was nothing else that could be done under the circumstances but invoke the 1925 version of “Rule 3.18.” Rowland waved his arms as if he were sweeping off a cluttered desk, signaling that the game was over and forfeited.

It was more a technical distinction than a summary judgment. In a scenario where the game continued with the Sox still down five runs with two out and one on in the ninth inning, the home team still had virtually no chance to win. Baseball Reference’s predictive algorithm suggests the game was all but over once Chicago made its first out in the ninth.

Under the rules at the time the Indians became winners by a 9 to 0 score. Batting and fielding records were kept, while pitchers—in particular Sloppy Thurston—were taken off the hook. Bob Knode was given his second error of the day, one that made national news. By early July he was back in the minor leagues where his “wagon tongue” played well enough to cover his well-publicized shortcomings on defense.

The forfeit ending made no difference to the crowd or the players. One loss was the same as another, and there wasn’t much behavior worth condemning. “It was one of those demonstrations that lacked any spark of hostility or danger,” according to the Cleveland Press. The forfeit may have mattered to the White Sox’ owner, Charles Comiskey, who was now automatically on the hook for a large fine for failing to maintain order in his ballpark.

In the end, though the number of people involved was enormous, the demonstration was more frolic than riot. “The bugs simply got tired of looking at a ball game that was going against them,” the Cleveland Press account explained. “They turned to other pursuits of interest. Poor sportsmanship is the worst indictment you can return against them.”

April 26, 1925 was a throwback moment, even by 1920s standards. It was “an echo from turbulent baseball days of the past,” according to one contemporary writer, momentarily restoring a bygone era where games were played with ardent fans festooned from every available vantage point, including the field, where they often struggled—unsuccessfully—to contain their exuberance.

From today we can see that this was also the last forfeit of its kind. There would be a few more forfeits in future decades, but they would hinge on conniving players; a performative Baltimore Napoleon; or various controlled substances. 1925 was the final time that a baseball forfeit was all in good fun.

Over on Clear the Field…

If you haven’t heard it yet, Ted and I released a new episode right before the holidays. It’s another story of my hometown fandom, from 1969/1970, a truly special moment when card-carrying Cub fans could even receive access to Fergie Jenkins’ hotel room service.

If you enjoy the stories here on Project 3.18, you’re going to love listening to Ted and I break some of our favorites down on the podcast. If you’re enjoying the show, please consider leaving us a rating on your podcast platform and/or telling a friend about us; we’re at a point where that really helps.

Translation: “Bob Knode not only hits the ball well but is also a skilled defender at first base. A year ago during the early season he was a league-leading hitter. Although he understandably fell off when the Barons were eliminated from contention, the former football star finished the season with a .295 batting average and was well-ranked among on defense as well.”

Boy, they really packed them in! It’s a wonder that one of the patrons on the field was not hit by a ball, or were they? I absolutely loved that 1924 Chicago Police pyramid photo! Where did you find that gem, Paul? Happy New Year!

OK, how does a guy get a nickname like "Pants"?