Playing Hurt - Part 1 of 2

In 1980, a flying Duracell battery almost knocked Dave Parker out of Pittsburgh.

We’d been saving this one. We planned to tell it at the end of July, to coincide with Dave Parker’s enshrinement in baseball’s Hall of Fame. Instead, we share it today to mark the recent passing of a baseball great. In 1980, Parker found himself at a low point—when the game stopped coming easy and some fans’ criticism landed hard. This part of Parker’s story is a reminder that true greatness requires talent and resilience. Dave Parker earned a place in Cooperstown because he had both.

The contract was one of the most lucrative deals ever signed by any player in any team sport—and one of the most complex. The two sides agreed to terms in the winter prior to the 1979 season, but the pact wasn’t signed until well into the season—it took months just to figure out how taxes would work.

The deal guaranteed $775,000 a year through 1983, plus deferred payments into the new millennium, plus performance escalators, plus attendance bonuses, plus, plus, plus… For all the intricacies, the contract’s bottom line was simple. For the first time ever, a single player would earn over a million dollars a year to play baseball. Dave Parker, right fielder for the Pittsburgh Pirates, had blown through the seven-figure ceiling.

“This is where I want to play,” Parker said at a January press conference announcing his gargantuan extension. “The ball club is my family1.”

The Pirates’ manager, Chuck Tanner, called Parker the “foundation for the future.” The right fielder was called a lot of nice things in this period. A June profile in SPORT magazine put its hyperbole in the form of a question:

Could he be the greatest player ever? Cobb’s fury, Ruth’s power, DiMaggio’s grace, Mays’ hustle, packaged in a 6’ 5” 230-pound 27-year-old who’d not yet peaked?

Most people getting an overheated comparison like that would instinctively recoil, but Parker didn’t flinch:

The greatest ever? With my attitude, I can’t see anything but that. I like to think of myself as one of the greatest now, not that I’ve had the longevity. But what I’ve done and the manner in which I’ve done it reflect my potential. I set goals to push myself, and what I say I can do—if I stay healthy—I can do.

Parker’s 1978 performance had cemented his reputation as one of the game’s young stars. He earned his second batting title and finished third in home runs. Over the last eight weeks of the season he hit .420. He won his second Gold Glove2 and had 13 outfield assists—that last number was down from prior years; his arm was now working on reputation alone. After breaking his face in a violent June collision with the Mets’ catcher, John Stearns, Parker returned 11 games later wearing first a hockey goalie’s mask and then a football face protector. 21 of 24 voters named him the National League’s MVP on vibes alone.

Through four seasons, Parker’s .323 average and 99 annual RBIs had earned him a place in Roberto Clemente’s right field at Three Rivers Stadium. If there was going to be a million-dollar player, few quibbled with it being Dave Parker, least of all the man himself.

“I wanted to make sure I became the first million-dollar player,” he told SPORT. “I can live up to it. The public needs to see a player who’s gotten security and then still goes out and applies himself. What I feel for the game makes me give 110 percent every time I go out there.”

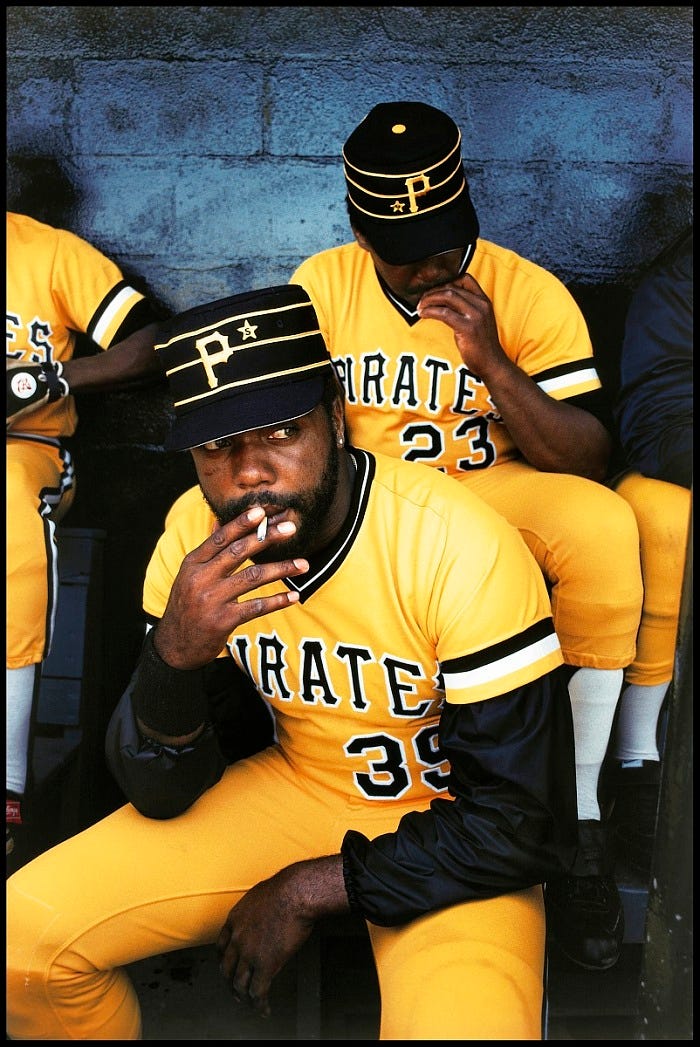

The 1979 Pittsburgh Pirates were fascinating and thrilling, running on diversity, high batting average, thumping disco, first baseman Willie Stargell’s esprit de corps, and a steady stream of clubhouse invective from Parker, a takedown comedian who spared no one but Stargell.

“Everybody has a different way of getting things done,” Chuck Tanner said. “Dave gets them ready by agitating them. Everybody winds up laughing and they go out relaxed and get the job done.”

Seeing Parker slam his bat on lockers and jokingly “accuse teammates of bigotry” often alarmed the uninitiated. But the Pirates understood him. “You don’t see anybody crawling into a shell when Dave starts screaming,” Stargell said. “We let everybody be themselves. We wouldn’t want Dave to sit in a corner and be quiet. He feels so good, he wants to scream and yell. That’s his way of being Dave.”

In August of that championship season, Parker made a typically propulsive swing during a game in Los Angeles and wrenched his knee. The ferocious swing revived an old high school football injury which had deprived him of some valuable cartilage at a young age and pushed him towards baseball despite his tight-end physique. Parker resolved to play through the injury.

Chuck Tanner was already of the belief that the “era of the 162-game player was over.” The manager warned Parker that he “played too hard” and urged him to rest, but in the 1970s a star got to make most of those decisions for himself, and Parker had already decided that he could only “live up” to his contract if he played.

There were no .400 months for Parker in 1979, which is another way of saying he hit over .300. His struggles, such as they were, lit a short fuse among some fans at Three Rivers Stadium.

At approximately $6,000 per game, Parker was making more than Babe Ruth made in a month, and that came with proportionate expectations. “He strikes out,” columnist Jim Murray wrote, “and people get mutinous.” Murray was sure it was about the money. “People like to throw snowballs at guys in top hats, and Parker qualifies. Nobody loves a Rockefeller.”

Parker had to endure more than boos that summer. His suburban Allison Park home was reportedly broken into three times. The top of his Mercedes convertible was slashed. His stacks of fan letters increasingly included missives written by people who professed to loathe him.

Parker told Murray his theory on the hard feelings, and in doing so the player demonstrated an unfortunate tendency to overgeneralize:

It’s hard for people to be able to relate to an individual making the kind of capital I do. It’s hard for them to relate to a man who makes the kind of money… Basically this is a coal-mining, steel-melting city—these people work hard for their money, they’re dedicated to their work, and it’s hard for them to imagine making this type of money playing games.

During the National League playoffs against the Cincinnati Reds Parker hit .333 and the Pirates swept, moving on to face the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series. Poor weather in Baltimore didn’t help his barking knee.

“Later in the Series, I couldn’t swing off the left leg,” he said, “and then I made an effort to swing to the opposite field.” Not long ago his swing had been perfect, beyond tinkering, but Parker knew he was not being paid a million dollars to hit well in June, and he did what he had to do. His October adjustments were seen and appreciated. Whenever he came to bat in the closing weeks of 1979, the right field stands at Three Rivers exploded. Banners with bullseyes were hung and the outfield bristled with signs heralding the Cobra, who was wounded, cornered, and thus even more dangerous.

During the World Series Dave Parker hit .345, helping Willie Stargell and the Pirates come back from a 3-1 deficit to win it all. Stargell would go to some lengths to remind people that his younger teammate played most of 1979 and the postseason with a knee about the size of a volleyball.

Dave Parker had played 158 games in 1979. He won a third Gold Glove, but his offensive output suffered along with his knee. His average dropped; he went from 30 homers to 25, from 118 RBI to 94. Explaining that the Pirates’ star “didn’t have a super year,” a report in The Sporting News demonstrates the standards being used:

[Parker] failed to win a third straight batting crown.

That’s another way of saying he hit .310.

By now Parker had realized his own oft-professed expectations of greatness had walled him in.

“It was a good year,” he said, “and maybe people have come to expect too much from me.”

“Dave doesn’t have to prove anything to anybody in baseball,” Tanner said. “He already has done that. Anybody who watches Parker play knows that they are seeing a super athlete.”

Parker’s contract wasn’t the only external influence that pushed him through pain. In November 1979 a reporter asked him about two pieces of mail he kept tacked to his locker. The first, a letter, began: “Hey boy. Why don’t you go back to black Africa?” and went on predictably—and unprintably—from there.

The other was more succinct: “With all your fortune and all your fame, you’re still a ******. Why don’t you go back where you came from?”

And so, the question. Dave, why keep this stuff on your locker?

“They give me inspiration,” Parker explained. “When I’m tired, I look at them.”

On October 19, just days after winning the World Series, the Pirates were bussed from Three Rivers Stadium to Pittsburgh’s Market Square for a noon “Fam-a-lee Reunion” rally. Celebrations like this one are lifetime-highlight moments for most athletes. The previous spring Dave Parker had colorfully told SPORT that receiving a standing ovation was better than sex, and here were several hundred thousand ovations happening at once, all for the Pirates. Parker reportedly skipped the festivities.

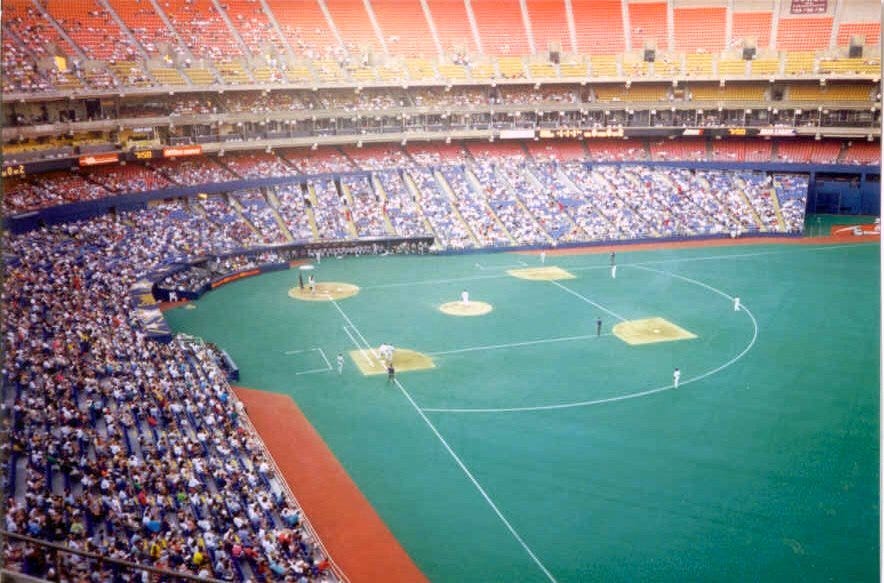

Pittsburgh’s next look at the champions came on April 18, 1980, the season’s home opener against the Chicago Cubs. Sister Sledge was in the house to celebrate with the team that turned their song “We Are Family” into a national phenomenon.

It was a packed house of 44,000, and security was busy. At C Gate, for general admission and standing room ticketholders, staff stood next to a pile of confiscated soda, beer, and wine.3 Outside, scalpers chatted with customers—and security guards—as they walked by: “Nah, man, I’m just showing this guy where my seats are.”

In between responding to a heart attack and running down a giddy trespasser in the outfield, the stadium security manager was called to the home dugout. Someone handed him a sweat-sock wrapped in wire. He unwound the wire and dumped out the sock’s contents: several pounds of nuts and bolts. It was a pre-planned, homemade missile, and someone had thrown it at Dave Parker as he stood in right field in his own ballpark.

Attempting to explain why someone would try to maim Parker, the security manager shook his head. “A lot of people resent him because of the money he makes.”

After the home opener, two guards were stationed in right field, assigned to watch Parker’s back.

In early July the reigning champs seemed stuck in third place. Parker was batting below .300 and hurting all over. His knee was a mess; surgery waiting to happen. There were calcium deposits, swelling, strained ligaments, and arthritis, and other bumps and bruises from hard play came and went.

All in all he guessed he was about 80% of himself. But for some people at Three Rivers Stadium, nothing less than his promised 110% would satisfy, and these critics seemed to be increasing in numbers.

If he struck out or bobbled a ball, Parker could hear them. Once he tried to make a leaping catch of a line drive near the outfield wall. While he failed to catch it, he managed to bat it down and prevent a home run. He was booed.

By this point his large ego was in worse shape than his knee. “I’m hurting from lack of support,” he said after a game with the Astros in Pittsburgh. “I’m like a guy without a hometown. It’s like I’m on the road all the time.”

Sympathetic observers repeated the time-honored truism—all the greats were booed in their own parks at one time or another. DiMaggio. Mantle. Mays. Aaron. Nobody ever booed a career .250 hitter. Historical comparisons for a sweat sock full of shrapnel were harder to find.

The situation was worsened by the absence of 40-year-old Willie Stargell, who missed much of the season as age finally came for its due. With Pops out, Parker was the de facto face of the franchise. But he (and his Black teammates) knew that replacing Stargell in Pittsburgh was a hopeless task.

“I was amazed when I first came to Pittsburgh and saw fans cheer Stargell even when he struck out,” third baseman Bill Madlock said that season. “Guys like Parker and me aren’t in that position. Parker can go four-for-four and then get booed after a strikeout.”

For the most part, Dave Parker had lived graciously in Stargell’s huge shadow. “Everything Willie gets, he deserves,” Parker said. “He has been an inspiration to me and it hurt me once when I read that I was jealous of Willie. It’s not true.”

July 20, 1980 was Willie Stargell Day. The Pirates organization decided to juice up a doubleheader with the Dodgers by throwing a bash for the World Series hero fans hadn’t gotten to see much of that season.

43,194 people came out to the stadium on a broiling summer day. The temperature on the Astroturf neared 120 degrees, and several fans left early with symptoms of heatstroke. Dave Parker ended up leaving early, too.

Parker was batting just .286 and had gone 1-for-3 with a double and two flyouts in the first game. The Pirates were losing, 3-2 in the top of the eighth inning, when Parker jogged gamely and deliberately to his station in right field. He arrived and turned to face the diamond. Then somebody threw something.

“I heard it buzz past my ear,” he recounted. The projectile landed hard on the turf in front of him. It bounced wildly, the velocity suggesting it had come from the upper deck. Parker followed behind. The right fielder was near first base when he picked up the nine-volt Duracell battery, copper on black, weighing about three ounces.

Parker decided his day was over. He walked into the dugout and flipped the battery to Tanner by way of explanation.

The Pirates’ clubhouse was quiet between games. The team’s famous stereo was off. Parker sat in front of his locker, looking at the floor, turning the battery slowly in his hand. “You pay your money,” he said, slowly, “you’ve got a right to do something verbally. But this…it’s getting unbearable.”

“The grating part for me is that it happened at home.” Home was supposed to be a refuge. Instead he was dodging batteries and screw-filled socks.

“I’ve had some great years here,” he said. He was almost talking to himself, trying to find his way across the gap between what he had accomplished and how little some people apparently thought of him. “Long-lasting,” he said. “That’s what I want to do. Last longer.”

But first he needed a break. Tanner, firmly in Parker’s corner, gave him the day’s second game off. “Chuck understood. I told him if he needed me to pinch-hit, I’d be around.”

Parker had hardly gathered himself before it was time to go back out on the field between games to honor Willie Stargell. The ceremonies lasted nearly an hour. There were presentations, remarks, and an outpouring of love for a man who gave it all right back. “I’m doing the best I can,” Stargell said, choking up during his brief remarks. “You’ve got to realize that you give us a lot of joy, too,” he told the crowd.

Given how his afternoon had ended, imagine how Dave Parker felt hearing that particular line. He was there with the rest of his teammates, on the field to honor the godfather, but his face was tight and hard. The day’s contrast loomed as large to Parker as he himself did in the batter’s box.

“A fan tried to hurt me on the day they all celebrated a Black man,” Parker wrote in his autobiography, Cobra. “That wasn’t objective racism. That was personal.”

Before the second game of the doubleheader, Pittsburgh’s vice president and general manager, Harding Peterson, took the public address microphone to have a sharp word with the crowd:

Pirate management is sick and tired of these acts, admittedly performed by a handful of our spectators. Should there be a next time for this needless and childlike activity, there is a strong possibility that the entire Pirate team will be removed from the field, even at the expense of forfeiting the game.

The second game was tied, 6-6, in the bottom of the eighth inning when Tanner sent Parker in to bat with the bases empty and one out. It would have been the perfect moment to hit a booming, cathartic home run, but if he had, you’d surely already know this story. He struck out, but his teammates mounted a two-run rally in the ninth to walk off the Dodgers and salvage Stargell Day.

Two days later, Dave Parker had processed what happened and was ready to move on—from Pittsburgh. With three years left on his contract, Parker told reporters his situation had reached a “point of no return,” and he’d asked management to trade him out of town:

I was hit in the head with a gas valve from a pellet gun last year. Sunday it was a battery. Earlier this year somebody tossed a sock full of nuts and bolts that weighed five pounds. A couple of years ago it was a bat.

It is in the best interests of both parties—the city of Pittsburgh and myself—that I complete my career without bodily harm.

Whoever feels that strongly about Dave Parker, we can eliminate that problem.

Dave Parker wasn’t the only one ducking for cover in 1980, and that fact was not lost on people at the time. But it was Parker’s headline-making reaction to the Duracell Incident that sparked a moment of national reflection while the Pirates’ star reached an inflection point in his career.

On July 14: “‘The Crowned Heads of Our National Game’”

“The ball club is my family.” Willie Stargell must have liked the sound of that.

SPORT reported that during 1979 spring training Parker broke his Gold Glove trophy apart and gave the ball to Stargell to thank him for years of support.

In 1980, apparently people could retrieve their confiscated alcohol and contraband as they left the stadium. Those were the days, weren’t they?

Dave Parker was awesome. Our Pirates could use someone today with that kind of oomph! Not much going on at PNC Park these days, other than Paul Skenes.

It’s a shame fans get violent to players. I can understand their reactions to their frustrations but not to the point of violence.

They should somehow react to juiced players; Consaco, A Rod, etc., but they don’t.

Far as salaries go there’s plenty players way over paid. These guys aren’t producing cures for diseases, but playing a kids game. I’ve said before it’s absurd they make in one game more than you or me in almost a year… and half that time they’re sitting.

I think their clauses should state half their salary goes to charity.

Dave definitely wasn’t respected by a few, I wonder why the fans didn’t turn in the culprits!

I also feel the HOF needs to react quickly in their decision to induct which may be a topic for another day.