Postscripts - Vol. 2

Adding on to a few recent stories, including a new bird sighting, an unexpected General, and a reader-submitted tip that led us to an unbelievable event.

This is Project 3.18, a newsletter where we remember moments when baseball didn’t go as planned, tell stories with fans, and write about history and culture through the lens of the National Game.

If you enjoy this article, you can use the provided button to subscribe and receive future stories for free in your inbox. And don’t miss the archives, full of forfeits, ejections, and wild tales from every era of baseball.

Look, we miss things sometimes. We really wish that never happened, but it does. Here’s the vicious cycle:

We publish a piece

Working on something else, we find a detail that really should have made it into our story

We curse and mutter, and put it in a file, where it weighs on us a little more each day or; if the new detail is shared by a reader, we clap our hands together in delight and prepare to publicly honor them and their contribution

Finally, seeking catharsis, we write a post that gives these little stories a moment of their own

Postscript: Voices of Ten Cent Beer Night

Recommended Reading: The Texas Brawl, (Re)Remembering Ten Cent Beer Night

Truth be told, after the June anniversary of TCBN, we thought we’d finally scratched that itch for a while, but leave it to our friend, author Scott Jarrett, to pull us back in. Scott was recently featured on a podcast series doing an episode on Ten Cent Beer Night. The series, Dark Side of the Land, is produced by several members of Cleveland’s Channel 19 news team, meaning the production values are high and the featured guests are top-shelf. In addition to Scott, who was on-point, they interviewed former player and manager Mike Hargrove, then of the Rangers, and later of the Indians, who offered a novel (if measured) perspective on what it was like for the players that night.

But the real surprise of the episode was the collection of sound bytes pulled directly from the radio broadcast of the game, using the voices of Joe Tait and Herb Score to narrate some of the night’s low points. We’d read the transcript but never heard the original audio…until now. Highly recommend.

Here’s a link to the podcast: The Beer Night Riot

Postscript: Always Two, There Are

Required Reading: Work, Fight, or Forfeit

A few weeks ago, we started our day with a cup of coffee and the newsletter from our fellow baseball writer and fellow Paul, Paul White, enjoying his write-up of the accomplishments of an underrated and commonly-named player from the Depression-era: Bob Johnson. Now, Paul probably didn’t intend for the following passage to generate many spit-takes from readers, but it sure got one from us:

Instantly, Johnson was a good major league hitter. He hit a double off veteran pitcher General Crowder of the Senators in his first major league game.

We beg your pardon—he hit a double off who??

What was our favorite Provost Marshal General, Enoch Crowder, doing pitching for the Senators in 1932, a year after he was reported to have passed away at the age of 73? We knew the guy was a hard worker but this was too much.

As you might suspect, this General Crowder was a completely different General Crowder—a player who got his nickname from the army lawyer who very nearly canceled his sport.

Alvin Floyd Crowder (no relation) was born on January 11, 1899. At the age of 20, he enlisted in the United States Army. This was in 1919, just months after World War I ended, so young Crowder’s service was less hair-raising than that of many of his older peers, but it was a job and he wanted to see the world. Just like his future namesake, Alvin Crowder also served at postings in Russia and later the Philippines, though the similarities end there. Enoch spent his time in Southeast Asia writing another country’s first constitution, while Alvin tried out pitching for the first time and found success.

Discharged in 1922, Crowder II realized he could make more money playing baseball than he’d made as a soldier. He signed with several minor-league teams across the country, bouncing around and landing with the Class A Birmingham Barons in 1925, where he made 59 appearances and pitched a whopping 229 innings, a performance that enticed the Pittsburgh Pirates to buy his contract. It didn’t work out, and Crowder was returned to the Barons for 1926, where he won 17 of 21 games he started that season.

Another thing happened at Birmingham. When he arrived in 1925, everybody called him Alvin, but by August 7, “the General” had reported for duty, when two different newspapers1 referred to him by that nom de guerre in their recaps of an exciting win.

A 1930 profile of Crowder documents the origin of his nickname to be precisely what you’d expect (though it erroneously connects the episode to an earlier team in his minor league career):

He acquired his nickname when he signed up to play [baseball] following his discharge from the service. The original General Crowder, you may recall, was a rather important individual during the war, and it was only natural, therefore, that Al, an ex-soldier, should become a “General” too.

And, let’s be clear, Crowder II was not just some guy with a convenient nickname who got an at-bat or two. This was a ballplayer of some note: named an All-Star in 1933; winning more than 20 games in back-to-back years; and pitching in three World Series for two different teams (going 1-3, but still).

Amazing, right? Not only were there two “General Crowders” active in post-War America, but the one we didn’t know about was the baseball guy.

Postscript: Bird Watching

Required Reading: For the Birds

Not only did we find another bird-strike incident in baseball, we seem to have found the first one. The circumstances were far from obscure: it happened in the major leagues, during a regular-season game. And yet, no one ever seemed to mention it again. Everybody talked about Dave Winfield, or Eric Davis, who, as we established, didn’t even hit a bird, but nobody talked about Willie Horton and the pigeon.

On April 14, 1974, the Boston Red Sox hosted the Detroit Tigers at Fenway Park. In the ninth inning, the Tigers trailed, 7-5, when left fielder Willie Horton came up to bat with two runners on base. Facing Boston’s Diego Segui, Horton fouled a pitch nearly straight up, where it collided with a pigeon (technically a rock pigeon) flying far above the field and with no reason to think it was in contested airspace. Horton’s errant foul struck the bird, which fell and landed just a few feet in front of home plate.

“It scared the hell outta me,” Bob Montgomery, Boston’s catcher said. “Willie jumped even higher.”

Warned that his club might be hearing from the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the Sox’ general manager, Dick O’Connell, took offense. “I’ll just refer them to Willie. He did it.”

This was the first bird-strike recorded in baseball (until we find the next one) and also the only fatality resulting from a foul2 ball.

This is typically the space where we share some nice things about the bird species in question, but, we’re sorry, it’s a bridge too far. Instead, we can only describe pigeons’ universal knack for waiting on the sidewalk as we approach from a block away, slowly drifting nearer and nearer to our evident walking path and then, at the very last second, startling and flying straight up in our face like we just appeared out of nowhere.

We’ll at least do the nice picture, though.

From Our Readers: This is Why We Never Keep Score

Just the other week, no doubt inspired by some of our recent forays into the ornithologically macabre, we received a package from our uncle, Roger Jackson. In addition to being one Project 3.18’s first and biggest fans, Roger is also a professional researcher, archivist, and one-half of an industrious pair of antique hunters, and he’d sent us a curious bit of ephemera picked up on a recent expedition.

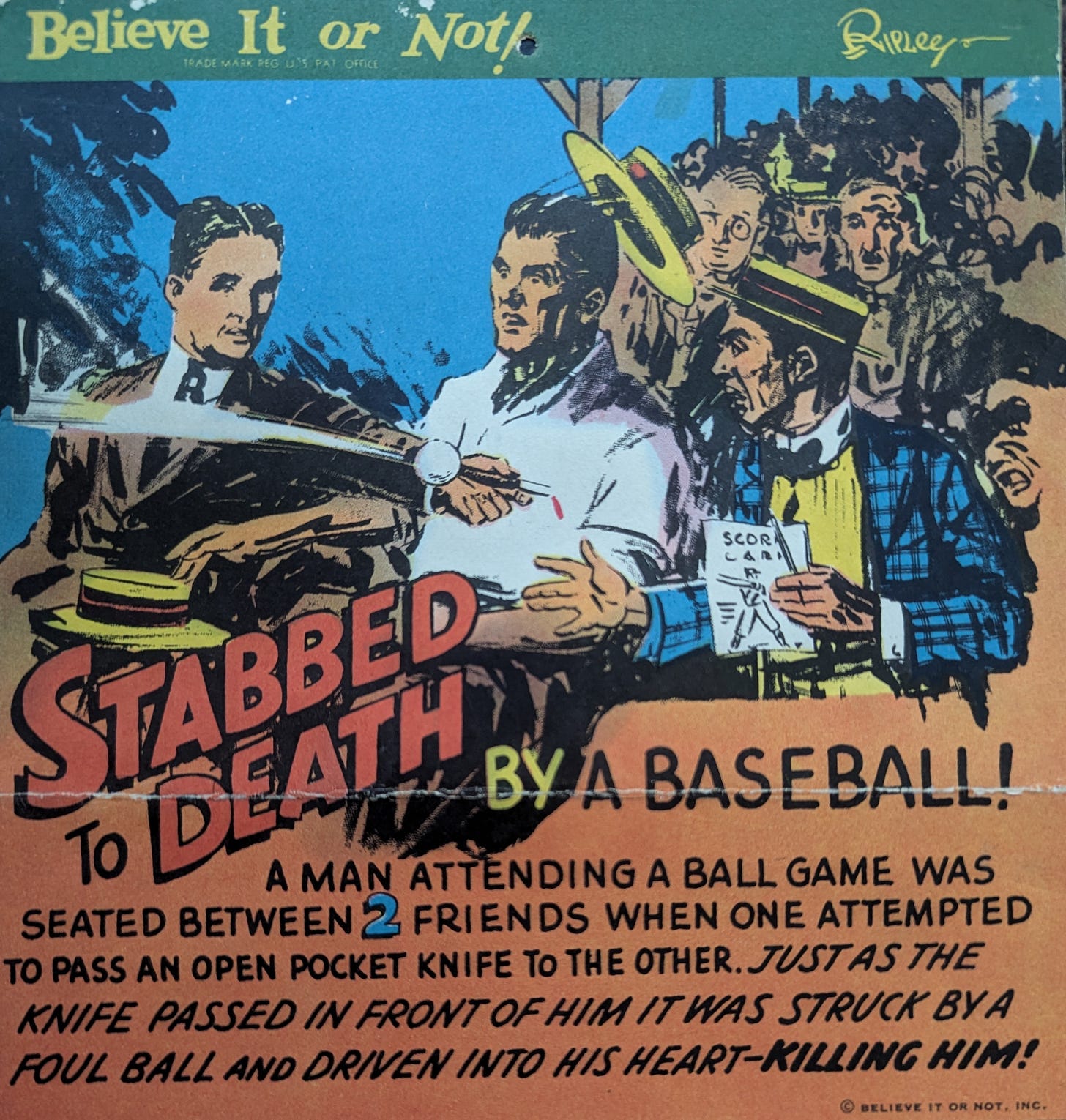

It was a 1945 promotional giveaway for the Oklahoma City Federal Savings and Loan. The pamphlet provided the bank’s calendar and contact information, in the vein of the annual Cubs schedule magnet we receive from our mortgage broker here in modern day. And while we were glad to have the bank’s contact information (2-2155, in case you need it), the notable part of the handout was the one-frame comic that served as its cover:

Not being terribly familiar with Ripley’s Believe It or Not, we initially assumed that this was some kind of pulpy eye-catching cover promoting a fictional story. But we did a little digging and, holy crap, this actually happened.

In Morristown, Ohio in 1902, two friends were sitting on a fence behind first base of the local baseball diamond, watching a game between the Morristown club and visiting Bethesda.

Frank Hyde, 19 years old, was keeping score, as reflected by the man in the blue jacket holding a scorecard in the illustration. Hyde’s pencil broke, and he asked his friend, Stanton Walker, if he could borrow his pocket knife to sharpen it. Walker, who had been whittling on a stick, obliged, handing over the open pocket knife in an most unfortunate way, with the blade pointed back at his own chest.

At that very moment, whoever was at bat (no account provides that detail) struck a foul ball that, by whatever is the opposite of a miracle, bounded across the field and up toward the very spot on the fence where the two boys were sitting. The ball actually struck the knife on the hilt, the impact driving the blade into Walker’s chest.

When Robert L. Ripley published his illustration of the event in 1939, nobody had any details about the boys, but Hyde, then a postal worker in Kalispell, Montana, saw the nationally-syndicated depiction of the worst moment of his life and came forward. Hyde said he was actually a player on the Morristown team, but hadn’t been feeling well that day, so he didn’t participate in the game.

Hyde recalled that after the ball struck the knife and the knife struck his friend, he asked “Did it hurt you?” Walker replied, “No, not much,” as he reflexively pulled the knife out and threw it away. He hopped down to go pick up the knife and suddenly collapsed. The blade had gone between his ribs and severed an artery, and he died more or less immediately. The members of the Morristown team subsequently took up a collection for Walker and some players even took responsibility for burying his coffin, trying to save his family the expense.

Foul balls are arguably the most dangerous element of baseball. It is has been this way for a very long time and remains so. Stanton Walker is by no means the only person killed by a foul ball (we found one other instance in 1905 just trying to track down Walker’s story, and there are plenty more), and serious injuries are even more common.

Grasping for any meaning amid the mind-breaking randomness of the tragedy, one newspaper covering the accident in 1902 wrote that “[Walker’s] lamentable death is doubtless without precedent, and shows how utterly unable we are to guard ourselves against the shafts of our merciless enemy.”

Thirty-seven years later, somebody shared Stanton Walker’s story with Ripley, who drew it up and published it in his syndicated newspaper strip. Eight years after that, “the Home Folks” at an Oklahoma bank reproduced it for their customers, one of whom somehow got it halfway across the country to Florence, Colorado, where it was waiting for our uncle in some file folder, nearly 80 years later. This particular chain of randomness ends in an opportunity for Project 3.18 to revive Stanton Walker’s story in 2024, and in doing so remind everyone that even with the modern safety netting, the Cubs (and all other baseball organizations) are not kidding about this, no matter how cute the messenger is:

And, for goodness’ sake, please don’t whittle at the ballpark.

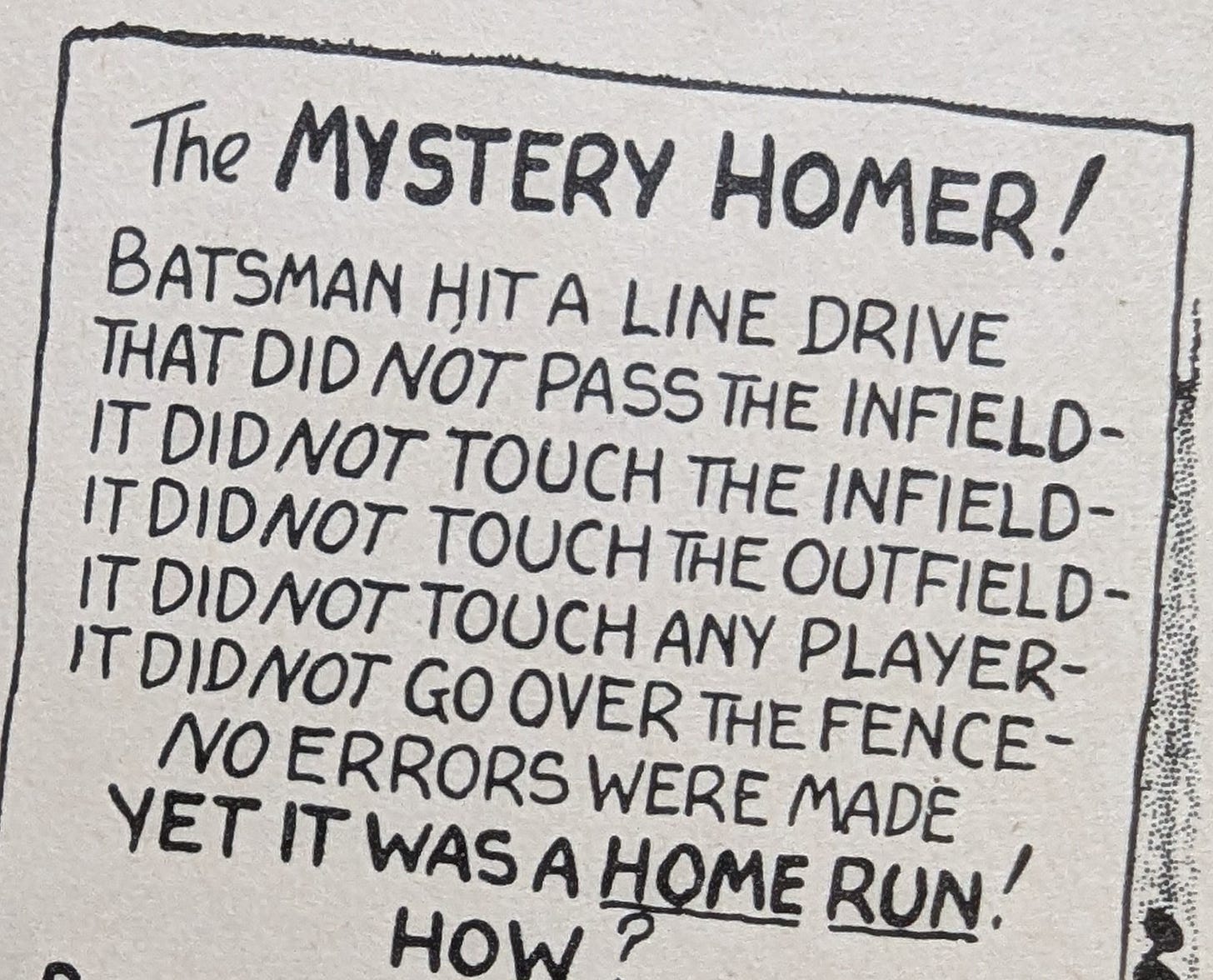

The Savings and Loan giveaway contained one other bit of Ripley’s baseball trivia (fun, this time) and we’ll end with that. We’ll put the answer at the end.

By the way, if YOU have interesting/fun/weird baseball ephemera to share and have been looking for a platform, know that Project 3.18 is here for you—send us an email!

And maybe we should say: we have no intention to re-brand this newsletter as RIP Baseball (not because we’d never go so dark, but because somebody got there first). But since Roger’s submission more than met the “when baseball didn’t go as planned” criterion, we did what we do.

Next time, we’re heading into the unknown—or at least a city we’ve yet to visit in our travels thus far. In 1980, at the end of a decade of misbehavior from the outfield crowds at Tiger Stadium, the president of the Detroit Tigers finally and fully solved the problem.

On September 9: “The Bleachers are Closed”

The solution to the Mystery Home Run, which supposedly occurred in Toronto in 1925, is that somebody hit a ball that struck third base and bounced off the base and into the seats. We couldn’t track down a particular incident with these parameters, but it certainly could be a true story; batted balls that strike the base are fair, and the rules used to say that fair balls that bounced into the seats were counted as home runs. We’ll believe it.

Both articles had bylines, not always a sure thing in this era, and since we’re already on the subject of nicknames, how about these for period appropriateness: “Bugs” Ramsey reported for the Birmingham Post-Herald and “Zipp” Newman for the Birmingham News. The quote marks are reproduced from the originals.

And we thought the wordplay was too obvious before…

Wow, Hyde started out not feeling well and ended up dead! “[B]y whatever was the opposite of a miracle,” for sure. This story is a real find. Everything had to conspire for this tragic outcome. What actually amazes me is that a bank thought it was appropriate material for a promotional magnet. Usually banks are more staid and proper. Hahahaha!

No TV’s back then. How about a horse dagnabit!