Work, Fight, or Forfeit - Part 1 of 3

In 1918, a seat-cushion battle at Shibe Park happened to coincide with an existential debate over baseball’s place in American life during World War I. What are the chances?

When we picked the July 20, 1918 forfeit as the next entry in our series on memorable games that weren’t, we didn’t realize that this would drop us right into the climax of the (first) Great War of the twentieth century. And we weren’t the only ones who seemed to miss this connection. We read every account of this game we could find (not many), but none of them mentioned the rather enormous sword of Damocles hanging over everyone’s heads that day.

It turns out that just as the Philadelphia Athletics forfeited a baseball game, the United States government was about to forfeit baseball—all of it—to the American war effort. Surprise!

On July 20, 1918, the Philadelphia Athletics forfeited a game to the Cleveland Indians after thousands among a bored and disillusioned crowd at Shibe Park began a battle royale using the heavy cushions provided for their grandstand seats. The cushion fracas “waged hotly for a full hour after play had been discontinued,” the Philadelphia Inquirer wrote of the forfeit. The account went on to jest that “the participants, probably misconstruing…the order that they must either ‘work or fight,’ had decided to fight.”

The “work or fight” part may mean little to a modern reader, but in July 1918 that line would have gotten a grim chuckle out of its audience, connecting as it did the nihilism seen in the stands at Shibe to the biggest crisis baseball had ever faced, one that was evolving faster than the papers could go to press.

That same day, James C. Dunn, owner of the Cleveland club who had just been gifted a game, put out a release signaling the end was nigh:

We will play a double-header with Philadelphia tomorrow and will then close the ballpark for the balance of the season. It is our desire to comply promptly with… the ruling on baseball. My men told me that they would not care to stand on the field and have leather-lunged fans shout at them to get useful jobs.

That night, Byron Bancroft (Ban) Johnson, the president and founder of the American League, announced that, barring any “unexpected developments,” the entire league would suspend operations after the games on July 21. At the peak of the nation’s involvement in World War I, the national game found itself confronting a glaring red light.

In early 1917, the “Great War” neared its third miserable anniversary. Throughout that time, the United States had remained a neutral party, wanting no part of the carnage tearing Europe apart. But after German U-boats began sinking American ships bound for England and a German plot to foment conflict with Mexico was uncovered, American leaders resolved to join the Allies and help “make the world safe for democracy.” Congress declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, but going to war took time in those days.

The first American soldiers arrived in France in June 1917, in very small numbers, but members of the full American Expeditionary Forces would not enter front-line combat until October. By the summer of 1918, however, entire divisions of American citizen-soldiers were engaged in the war, their presence quickly changing the trajectory of the conflict.

The nation had gone from neutrality to millions in combat in less than 18 months, a feat demonstrating both the totality of America’s commitment and the particular efficacy of one remarkable man, an individual perfectly designed to meet a very great national need in an exceedingly urgent moment.

We’d never heard of him.

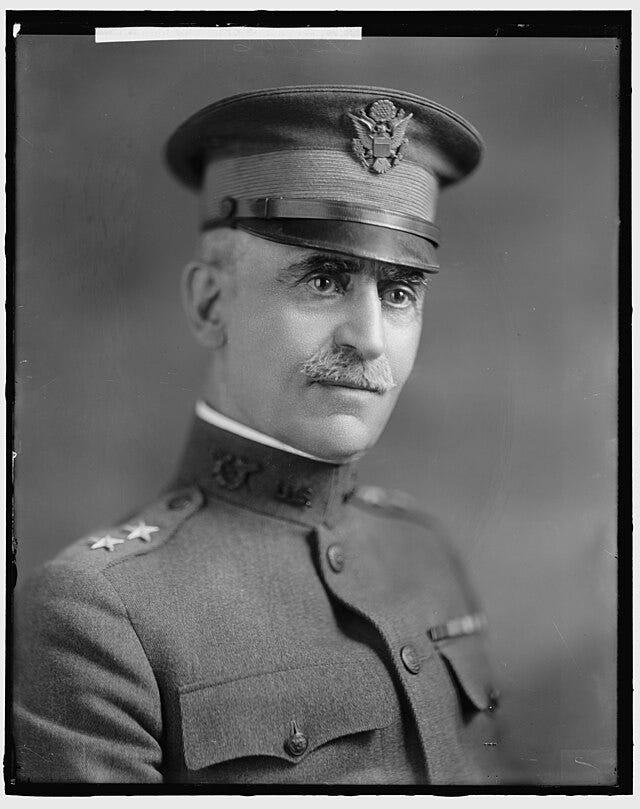

Enoch Crowder was born to a farming family in rural Missouri, and in 1859, “rural” in the United States could mean rather more than it does today. Consider that as a child, young Enoch took his schooling at Grand River College in northern Missouri, because that college was apparently the sole institution of learning in that entire region. After finishing whatever it was that a young boy learned at a college, a 16-year-old Crowder applied to the United States Military Academy at West Point and was accepted in 1877. He graduated in the middle of his class in 1881. Another cadet later remembered him as “a boy of moderate ability and promise, displaying no special talents or even ambition.”

Commissioned as a lieutenant in the Eighth Cavalry, during his first remote posting on the Texas/Mexico border, Crowder started to reveal all of the above, choosing to pursue a legal career as his side hustle.

In between patrols looking for cattle rustlers and studying for the bar exam, Crowder relaxed by perusing the limited selections of the officer’s library at Fort Brown, where he happened upon a book that had probably never been opened before. It was a comprehensive treatise on Civil War-era draft laws and the Union’s administration of conscription. To Enoch Crowder, the subject was somehow like catnip. After he studied it cover-to-cover, young Enoch decided he could improve upon its procedures and worked out an improved version. To be clear, no one asked him to do this—he did it for fun.

Given his evident scholarly aptitude, Crowder was reassigned to Missouri and detailed to teach Military Science and Tactics at the state university. While there (why not?), he completed a law degree to go with his professional license.

Late in the decade, Crowder returned to the field and took part in Army operations against Sitting Bull, the great leader of the Lakota tribe of Indigenous Americans. During those campaigns, Crowder the frontier lawyer volunteered to defend three different officers in court-martial proceedings and went 3-for-3 against the Army’s professional lawyers. He was quickly required to change jerseys and play for the Judge Advocate General corps.

At last in a role that welded both of his life’s passions into one glorious exercise of administering martial justice, Crowder rose through the ranks of the military’s lawyers while also circling the globe in the course of the Spanish-American War, where, in 1898, he threw together a little something to serve as the Philippines' post-war legal system. By 1911 he had risen to the military rank of Brigadier General and now led the Army’s JAG department, so naturally it was time for him to re-write the Manual for Court-Martial that governed military justice in the United States.

“He was a tireless worker, always on the anvil,” a contemporary wrote, and he was known to embark on 48 hour “days” when urgency demanded it. Who knows what else he would have gotten up to if not for the fact that in 1916, the United States government realized it might need a great many more soldiers than it had, very soon.

Crowder’s reputation as a subject-matter expert on conscription was well-known, and President Woodrow Wilson and Secretary of War Newton Baker asked him to oversee the formation of the draft law and its implementation. He was invested as “Provost Marshal General,” a role which seems generally but variably focused on military law enforcement, and put in charge of conscription. Crowder dusted off his fan fic draft system and submitted it to Congress.

Despite significant reservations of the rightness of conscription and fears that Americans simply wouldn’t accept it, the legislators knew quality work when they saw it, and in April 1917 the Selective Service Act passed the House and Senate by overwhelming bipartisan margins.

Less than three months later, on July 20, 1917, Provost Marshal General Crowder (“no need to be so formal–call me ‘General Crowder’”) and the Secretary of War drew the first numbers1 in the military draft lottery which would produce some three million soldiers from American society in less than 18 months. By the end of World War I, there would be more people (200,000) employed in the draft operations than there had been soldiers in the entire regular army in 1916 (165,000).

It probably won’t surprise you to know that in various accounts of Crowder’s remarkable life, we found nothing resembling a personal life or even a stray hobby. He was close to his extended family, visiting Missouri when he could (but how often could that have been?) but he never married. And while it’s hard to prove a negative, we think it’s fair to assume that no version of young Enoch–the boy taking college courses or the young lad writing large-scale military conscription regulations in his spare time–had any time for or interest in the game of baseball.

Professional baseball was still rising in prominence in the East around the time when Crowder graduated from West Point and headed deep into the West to start no less than three jobs, so it's very possible that he just completely missed the bus on baseball, like Project 3.18 did with pickleball.

Once the military draft began, Crowder began to notice a major flaw in his efficient process. The rules were pretty generous in offering men of military age deferrals from service on domestic grounds–if they were married and/or had one or more dependent children or other family members. These concerns made more sense in 1918 than they might today–men provided the primary and often sole income for the large majority of American households.

On the other hand, if you were a single, able-bodied (white) man between age 20 and 30 in 1917 and your draft number got called, off you went, no matter how productive a worker you were on the home front. And while there were no major labor shortages caused by the conscription of workers, to Crowder, the draft’s order of operations seemed increasingly and intolerably backward:

One of the unanswerable criticisms of the draft has been that it takes [single] men from the farms and from all useful employments and marches them past crowds of idlers and loafers away to the army. The remedy is simple–to require that any man pleading exemption on any ground shall also show that he is contributing effectively to the industrial welfare of the nation.

On May 23, 1918, the Provost Marshal General issued new amendments to the Selective Service procedures that governed the draft. The country’s most industrious man was going to war with the slacker class, and there was a ton of collateral damage:

After July 1, any registrant who is found by a local draft board to be a habitual idler or not engaged in some useful occupation shall be summoned before the board, given a chance to explain, and in the absence of a satisfactory explanation, to be inducted into the military service of the United States.

The new regulations became widely known as the “work or fight” rule. No matter what your domestic situation or draft number, the new orders meant that if you didn’t meet a standard of useful work and were otherwise fit to serve, you would be sent into service as soon as your local draft officials could get their hands on you.

The majority of the vocations singled out as “non-useful” in the announcement of the work-or-fight rule were specific and somewhat straightforward targets, no matter what you felt about the underlying premise. Elevator operators, restaurant servers, sales clerks were mentioned, as of course were “gamblers of all descriptions” and “the attendees of bucket shops and race tracks.”

One very niche field was called out with a specificity that suggested Crowder had some personal grudge against the occult, which would be very much in character. The regulations declared that “fortune tellers, clairvoyants, palmists, and the like” would need to exchange their cloaks and turbans for either overalls or military fatigues.

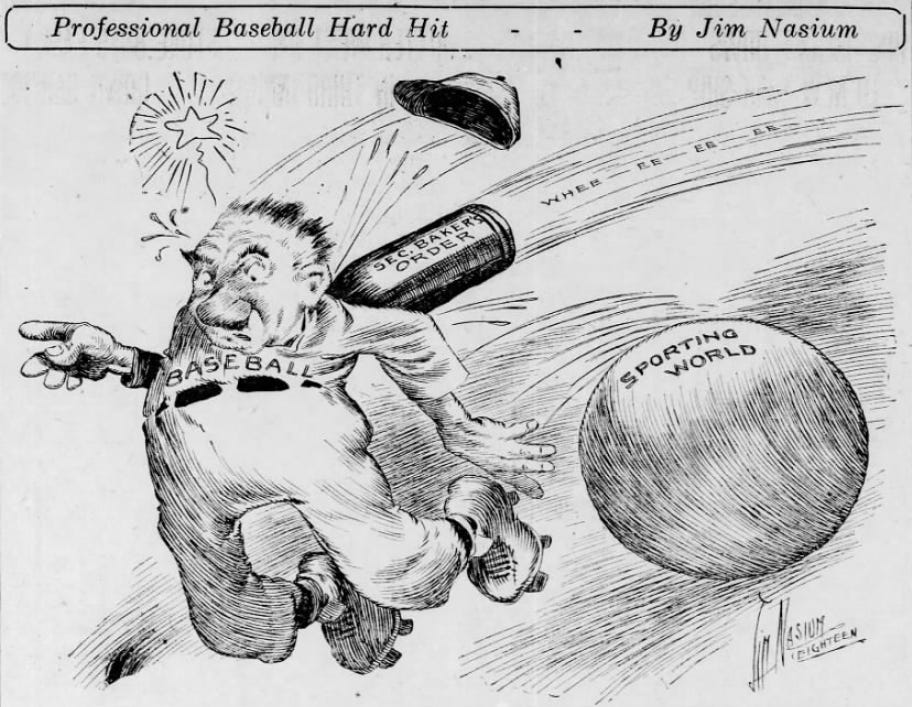

But by far the most ambiguous and controversial line from the order pertained to “persons, including ushers and other attendants, engaged and occupied in, and in connection with games, sports, and amusements.”

In one bullet point, Crowder appeared to have struck through the entire American entertainment industry, with only one listed exception: “actual performers in legitimate concerts, operas, or theatrical performances” could carry on.

For the normally-precise Provost Marshal General, these generalities were atypically vague. What was meant by “games, sports, and amusements?” Did that include organized, professional sports that played to big crowds and generated lots of money?

Throughout the decade, seasonal attendance at major league baseball games hovered around six million people, in a nation with 92 million people in 1910. The World Series was 15 years old and the game had already produced national stars, including Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Tris Speaker, and a multi-talented young pitcher named Babe Ruth was really looking like something for the Boston Red Sox. While not the juggernaut it would be only ten years later, in 1918, baseball’s national significance was unmissable.

Was the government really going to conscript professional baseball players? Writing the rules, Crowder could have easily carved baseball out of sports the way he carved the theater out of entertainment, but he didn’t.

It took a month to get a straight answer, but on June 22, eight days before the orders took effect, the Provost Marshal General confirmed it: baseball, even at the professional level, was a game, a sport, and an amusement, and under his work-or-fight order, those were nonproductive vocations. As such, the nation’s professional baseball players–stars, scrubs and journeymen–needed to either get real jobs or be prepared to go into military service.

For baseball, it was strike one.

There was no sentiment in the decision, but that was entirely the problem–sentiment was baseball’s superpower, but in Crowder they’d come up against America’s most unsentimental man.

Without exemptions, 90% of major league players were about to move to the front of the line to be drafted. Unless the leagues could quickly find a sympathetic ear in the government, the national game was over.

Thanks for checking out one of our classic period pieces. There will be increasingly more baseball as we go, but let’s be honest, nobody’s reading this in the hopes that we mention their favorite player, Bill Wambsganss. You’re here for the history stuff!

Here’s a link to the second part of our story: Part 2

Apologies and thanks to all those unlucky young men who were assigned to numbers 258 and 2,522, the very first pulls of the draft.

I came here for the baseball but I’m staying for the history stuff. This is among the best short pieces I’ve read anywhere this year. Stay the course please.

A great read, Paul - I look forward to the next two parts.